Military of the Yuan dynasty

The military of the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) were the armed forces of the Yuan dynasty, a fragment of the Mongol Empire created by Kublai Khan in China. The forces of the Yuan were based on the troops that were loyal to Kublai after the Division of the Mongol Empire in 1260. At first this Tamma, a frontier army drawn from all Mongol tribes for conquest of China, had no central organisation but was rather a loose collection of local warlords and Mongol princely armies. However the army was gradually reformed by Kublai Khan into a more systematic force.[1]

Guards

Yuan Cavalry were mainly Mongols while infantry were mainly Chinese. For his own bodyguards Kublai retained the use of the traditional Mongol Keshig.[2] Kublai created a new Imperial guard force, the suwei, of which half were Chinese and the other half ethnically mixed. By the 1300s even the Keshig were flooded with Chinese recruits.[3] The suwei were initially 6,500 strong but by the end of the dynasty it had become 100,000 strong. They were divided into wei or guards, each recruited from a particular ethnicity. Most wei were Chinese, while a few were Mongols, Koreans, Tungusic peoples, and Central Asians/Middle Easterners including Kipchaks, Alans and even one unit of Russians. The Keshig was converted into a administrative organisation instead.[4]

Administration

Unlike previous Chinese dynasties that strictly separated military and civilian power, the Yuan administration of military and civil affairs tended to overlap, as a result of traditional Mongol reliance on military matters. This was harshly criticised by the Chinese scholar officials at the time.[5] Military officers were allowed to pass on their positions to their sons or grandsons after death, retirement or sometimes even after a promotion.[6] Due to their Mongol background and unlike the previous Chinese dynasties, the Yuan granted feudal fief appanages with serfs throughout North China to military leaders, Mongol, Middle eastern/Central Asian and Han. The conflict between these military nobles with the Imperial government was a persistent feature until the end of the dynasty.[7]

Army

The Yuan dynasty created a "Han Army" (漢軍) out of defected Jin troops and army of defected Song troops called the "Newly Submitted Army" (新附軍).[8] Southern Song Chinese troops who defected and surrendered to the Mongols were granted Korean women as wives by the Mongols, whom the Mongols earlier took during their invasion of Korea as war booty.[9] The many Song Chinese troops who defected to the Mongols were given oxen, clothes and land by Kublai Khan.[10] As prize for battlefield victories, lands sectioned off as appanages were handed by the Yuan dynasty to Chinese military officers who defected to the Mongol side. The Yuan gave Song Chinese soldiers who defected to the Mongols juntun, a type of military farmland.[11] Cherik soldiers were non-nomad soldiers in the Mongol military. Jin defectors and Han Chinese conscripts were recruited into new armies formed by the Mongols as they destroyed the Jin dynasty and these played a critical role in the defeat of the Jin. Han Chinese defectors led by General Liu Bolin defended Tiancheng from the Jin in 1214 while Genghis Khan was busy going back north. In 1215 Xijing fell to Liu Bolin's army. The original Han cherik forces were created in 1216 and Liu Bolin appointed as their leading officer. As Han troops kept defecting from the Jin to the Mongols the size of Han cherik forces swelled and they had to be partitioned between different units. Han soldiers made up the majority of the Khitan Yelu Tuhua's army, while Juyin soldiers (Khitans, Tanguts, Ongguds and other vassal tribes) from Zhongdu made up Chalaer's army and Khitan made up Uyar's army. Chalaer, Yelu Tuhua and Uyar led three cherik armies in northern China under the Mongol commander Muqali in addition to his tamma armies in 1217-1218.[12] The first Han armies in the Mongol army were those led by defecting individual officers. There were 1,000 Han (Chinese) troops each in 26 units which made up three tumed arranged by Ogedei Khan on a decimal system. The Han officer Shi Tianze, Han officer Liu Ni and the Khitan officer Xiao Chala, all three of whom defected to the Mongols from the Jin led these three tumed. Chang Jung, Yen Shi and Chung Jou led three additional tumed which were created before 1234. The Han defectors were called the "Black Army" (Hei Jun) by the Mongols before 1235. A new infantry based "New Army" (Xin Jun) was created after the Mongols received 95,000 additional Han soldiers through conscription once the 1236 and 1241 censuses were taken after the Jin was crushed. Han cherik forces were used to fight against Li Tan's revolt in 1262. The New Army and Black Army had hereditary officer posts like the Mongol army itself.[13]

As a fully militarised society the Mongol rulers of the Yuan dynasty attempted to replicate elements of their own military in Chinese society. This was to be accomplished by establishing hereditary military households under the Bureau of Military Affairs that would provide troops for recruitment. Military households were grouped into four segments: Mongolian, Tammachi, Han, and the "Newly Adhered", each with different privileges including grants of stipends, food or tax exemptions. The Tammachi were Mongols and other steppe tribes on the southern edge of Mongolia. Han consisted of the North China forces that joined the Mongols before the 1250s while the "Newly Adhered" consisted of the South China forces that joined during the 1270s. The Han units were organised from Chinese warlord forces starting in 1232 under Ogedei Khan, and in 1241, the number of military households constituted 1 out of 7 households in North China, and formed an important element of the Mongol army. While most were peasant militia, some were capable of serving as cavalry forces equal to the Mongols, having been drawn from experienced frontier veterans or former Jin dynasty cavalrymen. The necessary numbers of troops for Kublai Khan's campaigns could only fulfilled by relying on the vast numbers of Southern Chinese soldiers that submitted in the 1270s, especially for naval expeditions which were composed entirely of Chinese and Koreans. Before Kublai, the early Mongol Empire had been accepting of autonomous Chinese warlords as key subordinates, but during the Yuan dynasty, there was considerable backlash from Mongols due to fear of Chinese insurrection, and these hereditary commanders were increasingly restricted. Due to the low status of military professions in China, and exploitation by corrupt administrators, desertion was a massive problem after the death of Kublai Khan.[14][15]

The Mongolian army was under direct command of the Emperor, while Tammachi were under semi-independent Mongol lords. Five Tammachi clans, the touxia, seem to have served the Yuan as allies under their own chiefs. Mongol forces were divided into toumans of 10,000 under a wanhu, divided into minghans of 1,000 under a qianhu, but in practice toumans ranged from 3,000 to 7,000 in strength.[16]

Mongols, now living in China, had immense difficulty meeting their military service obligations, as they needed to make a living as farmers and had no pastures to rear horses, having to purchase them at their own expense. By the 1300s many Mongol men could not even foot the cost for travel to enlist in the army. The Yuan army also contained a force known as the Tongshi Jun, which were Mongols who had fought against the Mongols for the Song dynasty. Other specialist troops were an Artillery Army, a Crossbow Army, a Miao Army (which was used to garrison Suzhou and Hangzhou in the 1350s), and other tribal forces from Southern China.[16]

There were also military artisan households which provided hereditary services for the production of military equipment such as weapons, armour, siege engines. These were under the command of the military registers.[17]

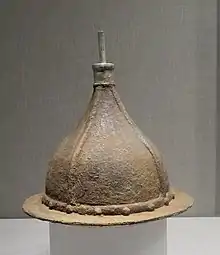

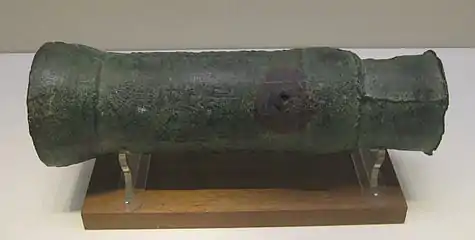

Chinese hand cannon, Yuan dynasty.

Chinese hand cannon, Yuan dynasty. Bronze cannon with inscription dated the 3rd year of the Zhiyuan era (1332) of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368); it was discovered at the Yunju Temple of Fangshan District, Beijing in 1935. It is similar to Xanadu gun.

Bronze cannon with inscription dated the 3rd year of the Zhiyuan era (1332) of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368); it was discovered at the Yunju Temple of Fangshan District, Beijing in 1935. It is similar to Xanadu gun.

The oldest confirmed surviving specimen of a metal cannon, the Xanadu Gun, is from Yuan dynasty China, dating to 1298.[18] Based on contextual evidence, historians believe another possibly older cannon, the Heilongjiang hand cannon, was used by Yuan forces against a rebellion by Mongol prince Nayan in 1287. The History of Yuan states that a Jurchen commander known as Li Ting led troops armed with hand cannons into battle against Nayan. By the time of Jiao Yu and his Huolongjing (a book that describes military applications of gunpowder in great detail) in the mid 14th century, the explosive potential of gunpowder was perfected, as the level of nitrate in gunpowder formulas had risen from a range of 12% to 91%, with at least 6 different formulas in use that are considered to have maximum explosive potential for gunpowder. By that time, the Chinese had discovered how to create explosive round shot by packing their hollow shells with this nitrate-enhanced gunpowder.[19]

Navy

Battles of 1277 involved massive naval forces on both sides. In the last battle near Guangzhou in 1279, which had been the last temporary capital of the Song dynasty, the Yuan captured more than 800 warships.

The Yuan was unusually sea-minded, attempting numerous maritime expeditions. After the Mongol invasions of Japan (1274, 900 ships, and in 1281, 4400 ships), Mongol invasion of Champa (1282), Mongol invasion of Java (1292, 1000 ships), in 1291 the Yuan attempted but did not ultimately proceed with an invasion of the Ryukyu Islands. However, none of these invasions were successful. Kublai contemplated launching a third invasion of Japan but was forced to back down due to fierce public disapproval. The Yuan era naval advances has been described as a successor of the Song dynasty achievements and an antecedent of the Ming's treasure fleets. An important function of the Yuan navy was the shipping of grain from the South to the capital of modern-day Beijing. There was fierce 50-year interdepartmental rivalry between the fleets shipping by the Grand Canal and shipping by the Yellow Sea, which ended with the eventual dominance of the Grand Canal in China until modern times.[20] The failed invasions also demonstrated a weakness of the Mongols – the inability to mount naval invasions successfully[21]

Shortly after the Mongol invasions of Japan (1274–1281), the Japanese produced a scroll painting depicting a bomb. Called tetsuhau in Japanese, the bomb is speculated to have been the Chinese thunder crash bomb.[22] Archaeological evidence of the use of gunpowder was finally confirmed when multiple shells of the explosive bombs were discovered in an underwater shipwreck off the shore of Japan by the Kyushu Okinawa Society for Underwater Archaeology. X-rays by Japanese scientists of the excavated shells provided proof that they contained gunpowder.[23]

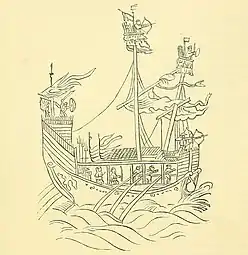

Sir Henry Yule's illustration of Yuan dynasty war junk used in the invasion of Java, 1871.

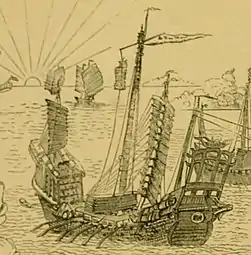

Sir Henry Yule's illustration of Yuan dynasty war junk used in the invasion of Java, 1871. Yuan ships as depicted by Japanese, 1293. Depicting the 1281 invasion of Japan.

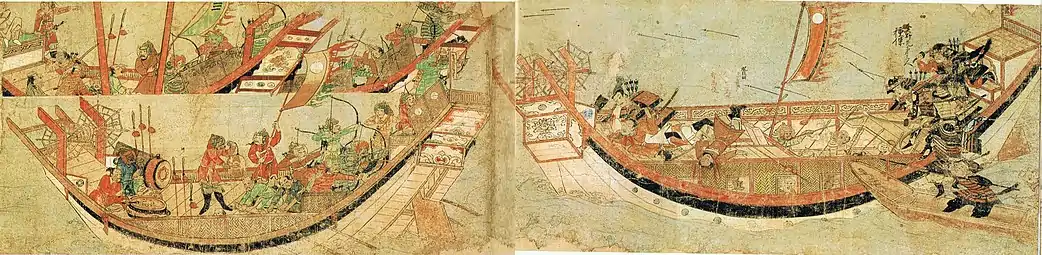

Yuan ships as depicted by Japanese, 1293. Depicting the 1281 invasion of Japan. Mongol ships, from scrolls on the Mongol invasions (Japanese: Mooko shuurai e-kotoba), by Fukuda Taika, 1846.

Mongol ships, from scrolls on the Mongol invasions (Japanese: Mooko shuurai e-kotoba), by Fukuda Taika, 1846.

References

- Peers, CJ (2006). Soldiers of the Dragon. Osprey Publishing. pp. 161. ISBN 1846030986.

- Twitchett, Dennis; Franke, Herbert, eds. (1994). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 6: Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 452. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- Twitchett, Dennis; Franke, Herbert, eds. (1994). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 6: Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 601. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- Peers, CJ (2006). Soldiers of the Dragon. Osprey Publishing. pp. 164–165. ISBN 1846030986.

- Twitchett, Dennis; Franke, Herbert, eds. (1994). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 6: Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 587–588. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- Twitchett, Dennis; Franke, Herbert, eds. (1994). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 6: Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 602. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- Twitchett, Dennis; Franke, Herbert, eds. (1994). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 6: Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 662. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- Hucker 1985, p.66.

- Robinson, David M. (2009). "1. Northeast Asia and the Mongol Empire". Empire's Twilight: Northeast Asia Under the Mongols (illustrated ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Harvard University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0674036086.

- Man, John (2012). Kublai Khan (reprint ed.). Random House. p. 168. ISBN 978-1446486153.

- Cheung, Ming Tai (2001). China's Entrepreneurial Army (illustrated, reprint ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 0199246904.

- May, Timothy (2016). May, Timothy (ed.). The Mongol Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia (illustrated, annotated ed.). ABC-CLIO. pp. 81, 213. ISBN 978-1610693400.

- May, Timothy (2016). May, Timothy (ed.). The Mongol Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia (illustrated, annotated ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 82. ISBN 978-1610693400.

- Twitchett, Dennis; Franke, Herbert, eds. (1994). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 6: Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 649–651. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- Charles O. Hucker (1985). Dictionary of bureaucratic terminology from Chou to Ch'ing dynasties, 11 22 B.C. to A.D. 1912. p. 66. ISBN 9780804711937. Retrieved 2016-05-27.

- Peers, CJ (2006). Soldiers of the Dragon. Osprey Publishing. pp. 162–164. ISBN 1846030986.

- Twitchett, Dennis; Franke, Herbert, eds. (1994). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 6: Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 654. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- "The World's Earliest Cannon (世界上最早的火炮)" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, V:7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, p. 264, 293-294, 345, ISBN 0-521-30358-3.

- Joseph Needham (1971). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 477–478. ISBN 0521070600.

- "The Mongols in World History | Asia Topics in World History". afe.easia.columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- Stephen Turnbull (19 February 2013). The Mongol Invasions of Japan 1274 and 1281. Osprey Publishing. pp 41–42. ISBN 978-1-4728-0045-9. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- Delgado, James (February 2003). "Relics of the Kamikaze". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. 56 (1). Archived from the original on 2013-12-29.