Minority languages of Croatia

The Constitution of Croatia in its preamble defines Croatia as a nation state of ethnic Croats, a country of traditionally present communities that the constitution recognizes as national minorities and a country of all its citizens. National minorities explicitly enumerated and recognized in the Constitution are Serbs, Czechs, Slovaks, Italians, Hungarians, Jews, Germans, Austrians, Ukrainians, Rusyns, Bosniaks, Slovenes, Montenegrins, Macedonians, Russians, Bulgarians, Poles, Romani, Romanians, Istro-Romanians ("Vlachs"), Turks and Albanians. Article 12 of the constitution states that the official language in Croatia is the Croatian language, but also states that in some local governments another language and Cyrillic or some other script can be introduced in official use. Croatia recognises the following languages: Albanian, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Czech, German, Hebrew, Hungarian, Macedonian, Montenegrin, Polish, Romanian, Romany, Russian, Rusyn, Serbian, Slovak, Slovenian, Turkish and Ukrainian.[1]

| Languages of Croatia | |

|---|---|

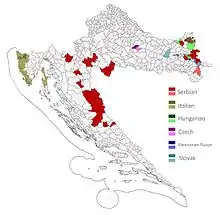

Map of municipalities with official minority languages | |

| Minority | |

The official use of minority languages is defined by relevant national legislation and international conventions and agreements which Croatia signed. The most important national laws are Constitutional Act on the Rights of National Minorities, Law on Use of Languages and Scripts of National Minorities and The Law on Education in language and script of national minorities. Relevant international agreements are European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages and Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities. Certain rights were achieved through bilateral agreements and international agreements such as Treaty of Osimo and Erdut Agreement.

The required 33.3% of the minority population in certain local government units for obligatory introduction of official use of minority languages is considered high, taking into account that The Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities of the Council of Europe considers a threshold from 10% to 20% reasonable.[2] Croatia does not always show favorable views on issues of minority rights but Croatian European Union accession process positively influenced public usage of minority languages.[3]

Official Minority Languages

Serbian

Education in Serbian language is primarily offered in the area of former Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia based on Erdut Agreement. With those school since 2005 there is also Kantakuzina Katarina Branković Serbian Orthodox Secondary School in Zagreb.

Serb National Council publish weekly magazine Novosti since December 1999. There are also monthly magazines Identitet, published by Serb Democratic Forum, Izvor, published by Joint Council of Municipalities, youth magazine Bijela Pčela and culture magazine Prosvjeta, both published by Prosvjeta and Forum published by Serb National Council from Vukovar. There are also three local radio stations in Serbian language in eastern Slavonia such as Radio Borovo. Since 1996 Central library of Prosvjeta works as the official Central Library of Serbs in Croatia as well.[4] Prosvjeta's library was established on 4 January 1948 and at that time it had 40,000 volumes mostly in national literature including most of the books from XVIII and XIX century.[4] In 1953 authorities made a decision to close the library and to deposit its books in Museum of Serbs of Croatia, National and University Library in Zagreb and Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts.[4] Library was reestablished in January 1995 and until 2016 it included more than 25,000 volumes in its collection.[4]

Department of South Slavic languages at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Zagreb has a The Chair of Serbian and Montenegrin literature.[5] Among the others, lecturers of Serbian literature at the university over the time were Antun Barac, Đuro Šurmin and Armin Pavić.[5]

Controversies

In the first years after introduction of new Constitutional Act on the Rights of National Minorities some local governments resisted implementation of its legal obligations. In 2005 Ombudsman report, municipalities of Vojnić, Krnjak, Gvozd, Donji Kukuruzari, Dvor and Korenica were mentioned as those that do not allow the official use of the Serbian language, although the national minority in these places meets the threshold provided for in the Constitutional Act.[6] The report pointed out that Serbian minority in Vukovar can not use the Serbian language although minority constituted less than one percent less population than it was prescribed by law.[6] After 2011 Croatian census Serbs of Vukovar meet the required proportion of population for co-official introduction of Serbian language but it led to Anti-Cyrillic protests in Croatia. In April 2015 United Nations Human Rights Committee urged Croatia to ensure the right of minorities to use their language and alphabet.[7] Committee report stated that particularly concerns the use of Serbian Cyrillic in the town of Vukovar and municipalities concerned.[7] The Constitutional Court of Croatia upheld the legislation on the use of minority languages. It relied on a newly developed concept of national identity.[8]

Italian

Italian minority has realized much greater rights on bilingualism than other minority communities in Croatia.[6] La Voce del Popolo is an Italian language daily newspaper published by EDIT (EDizioni ITaliane) in the city of Rijeka. Central Library of Italians in Croatia operates as a section of Public library in Pula.[9]

Hungarian

In 2004 Hungarian minority asked for introduction of Hungarian language in town of Beli Manastir as an official language, referring to the rights acquired prior to 1991.[6] Hungarian minority at that time constituted 8,5% of town population.[6] Central Library of Hungarians in Croatia operates as a section of Public library in Beli Manastir.[9]

Czech

6,287 declared Czechs live in Bjelovar-Bilogora County.[10] 70% of them stated that their native language is Czech.[10] Ambassador of Czech Republic in Croatia stated that intention to limit usage of Serbian Cyrillic would negatively affect Czechs and other minorities in Croatia.[11] Central Library of Czechs in Croatia operates as a section of Public library in Daruvar.[9] In an interview in 2011 Zdenka Čuhnil, MP for the Czech and Slovak minorities, stated that Czech minority, based on its acquired rights, have the legal right to use its language in 9 local units (municipalities or towns) while in practice usage of that right is enabled only in one unit and partially in one more.[12] She also stated that in the case of Slovak minority out of 6 units (5 based on acquired rights and one on the basis of proportionality) is free to use its rights only in one.[12]

Slovak

In 2011 there was 11 elementary schools in which students from Slovak minority were able to learn Slovak language.[13] Those schools were located in Ilok, Osijek, Soljani, Josipovac Punitovački, Markovac Našički, Jelisavac, Miljevci, Zdenci, Lipovljani and Međurići.[13] Gymnasium in Požega was the first high school in Croatia to introduce Slovak language education into its elective curriculum.[14] Union of Slovaks in cooperation with the Slovak Cultural Center in Našice publish magazine Prameň in Slovak language.[15] On the 200th anniversary of birth of Štefan Moyses in 1997 Croatian branch of Matica slovenská set a bilingual memorial plate at the building of the Gornji Grad Gymnasium in Zagreb.[16] In 2003 second bilingual plate commemorating the work of Martin Kukučín was set up in Lipik.[16] Matica slovenská in Zagreb published more than 10 books in Slovak language over the years.[16] In 1998 Central Library of Slovaks in Croatia was established as a section of Public library in Našice and as of 2016 its users had access to more than 4,000 volumes.[17]

Rusyn

Central Library of Rusyns and Ukrainians in Croatia operates as a section of Public libraries in Zagreb.[9] Library was established on 9 December 1995 and today part of its collection is accessible in public libraries in Vinkovci, Lipovljani, Slavonski Brod, Vukovar and Petrovci.[18]

German

Central Library of Austrians and Germans in Croatia operates as a section of Public library in Osijek.[9]

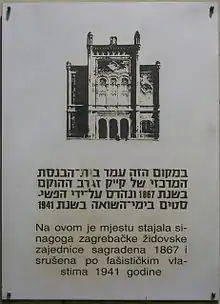

Yiddish and Hebrew

Organisation Zagreb Yiddish Circle is club that organizes courses in Yiddish language, lectures on Jewish history, linguistics and culture, movie nights, and hosts a Yiddish book club.[19]

Ukrainian

Ukrainian language classes are four schools in Lipovljani, Petrovci, Kaniža and Šumeće, attended by about 50 students.[20] Central Library of Rusyns and Ukrainians in Croatia operates as a section of Public libraries in Zagreb.[9] Library was established on 9 December 1995 and today part of its collection is accessible in public libraries in Vinkovci, Lipovljani, Slavonski Brod, Vukovar and Petrovci.[18]

Romani

Croatian Parliament formally recognised Romani Language Day on May 25, 2012.[21] Veljko Kajtazi, Romani community MP, stated that he will advocate to have the Roma language included on the list of minority languages in Croatia during his term in office.[21]

Istro-Romanian

The Istro-Romanian language is one of the smallest minority languages spoken in Croatia with fewer than 500 speakers concentrated mainly in the north-eastern part of the Istrian Peninsula. While the language is not officially recognized in the Constitution of Croatia under that name (the Constitution references Romanians and "Vlachs"), it is specifically recognized as such in the Statute of the Istrian Region[22] and in the Statute of the Municipality of Kršan.[23] In 2016, with funding from the Romanian government, the school in the village of Šušnjevica was fully renovated and is expected to start offering education in Istro-Romanian.[24]

Municipalities with minority languages in official use[25]

| Municipality | Name in minority language | Language | Affected settlements | Introduced based on | Population (2011) | Percentage of affected minority (2011) |

County |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Končanica | Končenice | Czech | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 2,360 | 47,03% | Bjelovar-Bilogora |

| Daruvar | Daruvar | Czech | Ljudevit Selo, Daruvar, Donji Daruvar, Gornji Daruvar and Doljani | Town Statute | 11,633 | 21.36% | Bjelovar-Bilogora |

| Kneževi Vinogradi | Hercegszöllős | Hungarian | Kneževi Vinogradi, Karanac, Zmajevac, Suza, Kamenac, Kotlina[26] | Constitutional Act | 4,614 | 38,66% | Osijek-Baranja |

| Bilje | Bellye | Hungarian | All settlements | Municipality Statute | 5,642 | 29.62% | Osijek-Baranja |

| Ernestinovo | Ernestinovo | Hungarian | Laslovo | Municipality Statute | 2.225 (2001) | 22% (2001) | Osijek-Baranja |

| Petlovac | Baranyaszentistván | Hungarian | Novi Bezdan | Municipality Statute | 2,405 | 13.72% | Osijek-Baranja |

| Tompojevci | Tompojevci | Hungarian | Čakovci | Municipality Statute | 1,561 | 9.01% | Vukovar-Srijem |

| Tordinci | Tardhoz | Hungarian | Korođ | Municipality Statute | 2,251 (2001) | 18% (2001) | Vukovar-Srijem |

| Punitovci | Punitovci | Slovak | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 1.850 (2001) | 36,94% | Osijek-Baranja |

| Našice | Slovak | Jelisavac | Town Statute | 16,224 | 5.57% (2001) | Osijek-Baranja | |

| Vrbovsko | Врбовско | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 5,076 | 35,22% | Primorje-Gorski Kotar |

| Vukovar | Вуковар | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 27,683 | 34,87% | Vukovar-Srijem |

| Biskupija | Бискупија | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 1,699 (2001) | 85,46% | Šibenik-Knin |

| Borovo | Борово | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 5,056 | 89,73% | Vukovar-Srijem |

| Civljane | Цивљане | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 239 | 78,66% | Šibenik-Knin |

| Donji Kukuruzari | Доњи Кукурузари | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 1,634 | 34,82% | Sisak-Moslavina |

| Dvor | Двор | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 6,233 | 71,90% | Sisak-Moslavina |

| Erdut | Ердут | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 7,308 | 54,56% | Osijek-Baranja |

| Ervenik | Ервеник | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 1 105 | 97,19% | Šibenik-Knin |

| Gračac | Грачац | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 4,690 | 45,16% | Zadar |

| Gvozd | Гвозд or Вргинмост | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 2,970 | 66,53% | Sisak-Moslavina |

| Jagodnjak | Јагодњак | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 2,040 | 65,89% | Osijek-Baranja |

| Kistanje | Кистање | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 3,481 | 62,22% | Šibenik-Knin |

| Krnjak | Крњак | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 1,985 | 68,61% | Karlovac |

| Markušica | Маркушица | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 2.576 | 90,10% | Vukovar-Srijem |

| Negoslavci | Негославци | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 1.463 | 96,86% | Vukovar-Srijem |

| Plaški | Плашки | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 2,292 (2001) | 45,55% | Karlovac |

| Šodolovci | Шодоловци | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 1,653 | 82,58% | Osijek-Baranja |

| Trpinja | Трпиња | Serbian | Village Ćelije excluded in municipality Statute[27] | Constitutional Act | 5,572 | 89,75% | Vukovar-Srijem |

| Udbina | Удбина | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 1,874 | 51,12% | Lika-Senj |

| Vojnić | Војнић | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 4,764 | 44,71% | Karlovac |

| Vrhovine | Врховине | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 1,381 | 80,23% | Lika-Senj |

| Donji Lapac | Доњи Лапац | Serbian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 2,113 | 80,64% | Lika-Senj |

| Kneževi Vinogradi | Кнежеви Виногради | Serbian | Kneževi Vinogradi and Karanac[26] | Municipality Statute | 4,614 | 18.43% | Osijek-Baranja |

| Nijemci | Нијемци | Serbian | Banovci and Vinkovački Banovci | Municipality Statute | 4,705 | 10,95% | Vukovar-Srijem |

| Grožnjan | Grisignana | Italian | All settlements | Constitutional Act | 785 (2001) | 39,40% | Istria |

| Brtonigla | Verteneglio | Italian | All settlements | Constitutional Act (2001) | 1,873 (2001) | 37.37% (2001) | Istria |

| Buje | Buie | Italian | All settlements | Town Statute | 5,127 | Istria | |

| Cres | Cherso | Italian | All settlements | Town Statute | 2,959 (2001) | Primorje-Gorski Kotar | |

| Novigrad | Cittanova | Italian | All settlements | Town Statute | 4,345 | 10.20% | Istria |

| Poreč | Parenzo | Italian | All settlements | Town Statute | 16,696 | 3.2% | Istria |

| Pula | Pola | Italian | All settlements | City Statute | 57,460 | 4.43% | Istria |

| Rijeka | Fiume | Italian | All settlements | City Statute | 128,624 | 1.90%% | Primorje-Gorski Kotar |

| Rovinj | Rovigno | Italian | All settlements | Town Statute | 14,294 | 11,5% (2001) | Istria |

| Umag | Umago | Italian | All settlements | Town Statute | 13,467 (2001) | 18.3% (2001) | Istria |

| Vodnjan | Dignano | Italian | All settlements | Town Statute | 6,119 | 16.62% | Istria |

| Bale | Valle d'Istria | Italian | All settlements | Municipality Statute | 1,127 | 36,61% (1991) | Istria |

| Fažana | Fasana | Italian | All settlements | Municipality Statute | 3.635 | 4,82% (1991) | Istria |

| Funtana | Fontane | Italian | All settlements | Municipality Statute | 831 (2001) | 3,12% (1991) | Istria |

| Kaštelir-Labinci | Castellier-Santa Domenica | Italian | All settlements | Municipality Statute | 1,334 (2001) | Istria | |

| Ližnjan | Lisignano | Italian | Šišan | Municipality Statute | 3.965 | Istria | |

| Motovun | Montona | Italian | All settlements | Municipality Statute | 983 (2001) | 9,87% (2001) | Istria |

| Oprtalj | Portole | Italian | All settlements | Municipality Statute | 850 | Istria | |

| Tar-Vabriga | Torre-Abrega | Italian | All settlements | Municipality Statute | 1,506 (2001) | Istria | |

| Višnjan | Visignano | Italian | Višnjan, Markovac, Deklevi, Benčani, Štuti, Bucalovići, Legovići, Strpačići, Barat and Farini | Municipality Statute | 2,187 (2001) | 9.1% (2001) | Istria |

| Vrsar | Orsera | Italian | All settlements | Municipality Statute | 2,703 (2001) | 5,66% (1991) | Istria |

| Bogdanovci | Богдановци | Pannonian Rusyn | Petrovci | Municipality Statute | 1,960 | 22.65% | Vukovar-Srijem |

| Tompojevci | Томпојевци | Pannonian Rusyn | Mikluševci | Municipality Statute | 1,561 | 17.38% | Vukovar-Srijem |

History

During Napoleon I's invasion of Croatia in the early 19th century, a large portion was of the country was converted into the Illyrian Provinces (Provinces illyriennes) and incorporated as a French province in 1809.[28] French rule established the official language of the autonomous province to be French followed by Croatian, Italian, German, and Slovene.[29][30] According to France's Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, about 6% of Croatians are fluent in basic conversation in French.[31]

European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages became a legally binding for Croatia in 1997.[32]

See also

References

- Franceschini, Rita (2014). "Italy and the Italian-Speaking Regions". In Fäcke, Christiane (ed.). Manual of Language Acquisition. Walter de Gruyter GmbH. p. 546. ISBN 9783110394146.

- "Minorities in Croatia Report, page 24" (PDF). Minority Rights Group International. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- "Language Policy in Istria, Croatia–Legislation Regarding Minority Language Use, page 61" (PDF). Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, European and Regional Studies, 3 (2013) 47–64. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- Snjezana Čiča (April 2016). "Centralna biblioteka Srpskog kulturnog društva "Prosvjeta" – centar kulture Srba u Hrvatskoj". Novosti-Hrvatsko knjižničarsko društvo. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. "The Chair of Serbian and Montenegrin Literature". University of Zagreb. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- "The Position of National Minorities in the Republic of Croatia–Legislation and Practice, page 18" (PDF). ombudsman.hr. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- "UN calls on Croatia to ensure use of Serbian Cyrillic". B92.net. 3 April 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- Toplak, Jurij; Gardasevic, Djordje (14 November 2017). "Concepts of National and Constitutional Identity in Croatian Constitutional Law". Review of Central and East European Law. 42 (4): 263–293. doi:10.1163/15730352-04204001. ISSN 1573-0352.

- "Središnje knjižnice nacionalnih manjina". Ministarstvo kulture. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- "DAN MATERINJEG JEZIKA". Bjelovar-Bilogora County. 22 February 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- "Košatka: Reći 'ne može' ćirilici znači biti i protiv Čeha". Večernji list. 18 December 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- Obradović, Stojan (5 November 2011). "Gradovi i općine zloupotrebljavaju stečeno pravo: intervju s Zdenkom Čuhnil". Identitet (in Serbian). Zagreb: Serb Democratic Forum (159).

- Vinco Gazdik (21 May 2011). "Kako žive Slovaci u Hrvatskoj". T-portal. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- Ljiljana Marić (24 May 2013). "Prva srednja škola u Hrvatskoj u kojoj će se učiti slovački jezik". Večernji list. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- "Prameň-KULTÚRNO-SPOLOČENSKÝ ČASOPIS SLOVÁKOV V CHORVÁTSKU". Union of Slovaks. Archived from the original on 21 June 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- "Matica slovačka Zagreb". Matica slovačka Zagreb. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- Ružica Vinčak (April 2016). "Središnja knjižnica Slovaka radi na povezivanju dvije kulture i dva naroda". Novosti-Hrvatsko knjižničarsko društvo. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- "Središnja knjižnica Rusina i Ukrajinaca Republike Hrvatske". Public libraries of City of Zagreb. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- "zagreber yidish-krayz (Zagreb Yiddish Circle)-About". Zagreb Yiddish Circle. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- "Ukrajinci u Republici Hrvatskoj". Embassy of Ukraine in Zagreb. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- "World Roma Language Day marked in Croatian Parliament". Croatian Parliament. 5 November 2014. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- "Statute of the Istrian Region". Istrian Region. 19 May 2003. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- "Status Općina Kršan". Municipality of Kršan. 29 July 2009. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- "La Șușnevița, în Croația, s-a inaugurat prima școală refăcută de Statul Român pentru istroromânii din localitate". 17 November 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- Government of Croatia (October 2013). "Peto izvješće Republike Hrvatske o primjeni Europske povelje o regionalnim ili manjinskim jezicima" (PDF) (in Croatian). Council of Europe. pp. 34–36. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- "Statut Općine Kneževi Vinogradi , article 15" (PDF). Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- "Statut Općine Trpinja" (PDF). Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- "Croatian-French relations". Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- "Croatian-French relations". Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- "Illyrian Provinces | historical region, Europe". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- "France and Croatia". Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- "Europe and Croatia are living and protecting multilingualism". GONG (organization). 10 December 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2015.