Languages of the United Kingdom

English, in various dialects, is the most widely spoken language of the United Kingdom,[10] but a number of regional languages are also spoken. There are 14 indigenous languages used across the British Isles: 5 Celtic, 3 Germanic, 3 Romance, and 3 sign languages: 2 Banszl and 1 Francosign language. There are also many languages spoken by people who arrived more recently in the British Isles, mainly within inner city areas; these languages are mainly from South Asia, Eastern and Western Europe.[11]

| Languages of the United Kingdom | |

|---|---|

English Scots Welsh Scottish Gaelic | |

| Main | English (98%;[1] national and de facto official)[a][2][3][4] |

| Regional | Cornish (historical) (<0.01% L2) |

| Minority | Scots (2.5%),[5] Welsh (1.3%),[6] Ulster Scots (0.05%),[7] Scottish Gaelic (0.1%), Irish (0.1%),[a] Angloromani, Beurla Reagaird, Shelta |

| Immigrant | Polish, Punjabi, Urdu, Bengali/Sylheti, Gujarati, Arabic, French, Chinese, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil |

| Foreign | French (23%), German (9%), Spanish (8%)[b][8] |

| Signed | British Sign Language, (0.002%)[c][9] Irish Sign Language, Northern Ireland Sign Language, Signed English |

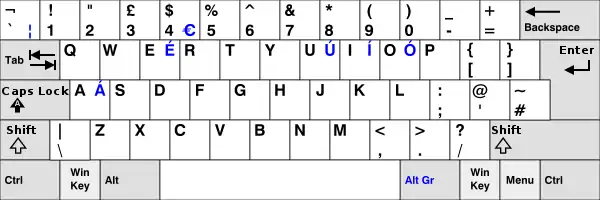

| Keyboard layout | |

The de facto official language of the United Kingdom is English,[3][4] which is spoken by approximately 59.8 million residents, or 98% of the population, over the age of three.[1][2][12][13][14] (According to 2011 census data, 864,000 people in England and Wales reported speaking little or no English.[15]) An estimated 900,000 people speak Welsh in the UK,[16] an official language in Wales[17] and the only de jure official language in any part of the UK.[18] Approximately 1.5 million people in the UK speak Scots—although there is debate as to whether this is a distinct language, or a variety of English.[5][19]

List of languages and dialects

Living

The table below outlines living indigenous languages of the United Kingdom (England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland). The languages of the Crown Dependencies (the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man) are not included here.

| Language | Type | Spoken in | Numbers of speakers in the UK |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Germanic (West Germanic) | Throughout the United Kingdom | 59,824,194; 98% (2011 census)[1] |

| Scots (Ulster Scots in Northern Ireland) | Germanic (West Germanic) | Scotland (Scottish Lowlands, Caithness, Northern Isles) and Berwick-upon-Tweed Northern Ireland (Counties Down, Antrim, Londonderry) |

2.6% (2011 census)

|

| Welsh | Celtic (Brythonic) | Wales (especially west and north) and parts of England near the Welsh–English border Welsh communities in major English cities such as London, Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool. |

1,123,500; 1.7% (2019 Wales figures, with England, Scotland and Northern Ireland estimated figures from 2011 census) |

| British Sign Language | BANZSL | Throughout the United Kingdom | 125,000[24] (2010 data) |

| Irish | Celtic (Goidelic) | Northern Ireland, with communities in Glasgow, Liverpool, Manchester, London etc. | 95,000[25] (2004 data) |

| Angloromani | Mixed | Spoken by English Romanichal Traveller communities in England, Scotland and Wales | 90,000[26] (1990 data) |

| Scottish Gaelic | Celtic (Goidelic) | Scotland (Scottish Highlands and Hebrides with substantial minorities in various Scottish cities) A small community in London |

65,674 total,[4] (Scotland's 2001 Census) though those who have fluency in all three skills is 32,400[27] |

| Cornish | Celtic (Brythonic) | Cornwall (even smaller minorities of speakers in Plymouth, London, and South Wales) | 557[28] (2011 data) |

| Shelta | Mixed | Spoken by Irish Traveller communities throughout the United Kingdom | Est. 30,000 in UK. Fewer than 86,000 worldwide.[29] |

| Irish Sign Language | Francosign | Northern Ireland | Unknown |

| Northern Ireland Sign Language | BANZSL | Northern Ireland | Unknown |

Anglic

- English (British English)

- English English (as spoken in England)

- Northern English

- Cheshirian dialect

- Cumbrian

- Northumbrian

- Geordie (of Newcastle-upon-Tyne and surrounding area)

- Lancastrian

- Mackem (of Sunderland and surrounding area)

- Mancunian

- Yorkshire/Tyke

- Scouse (Liverpool and surrounding area)

- East Midlands English

- West Midlands English

- Black Country (of Dudley, Wolverhampton, Walsall and Sandwell)

- Brummie (spoken in Birmingham)

- Potteries (North Staffordshire, centred on Stoke on Trent)

- Southern English English

- East Anglian

- Estuary English

- London

- West Country dialects (Bristol, Devon, Dorset, Somerset; also parts of Gloucestershire and Herefordshire)

- Northern English

- Scottish English

- Welsh English

- Cardiff dialect (additional varieties of which spoken throughout South Wales)

- Hiberno English

- Sign Supported English (a sign language based on English, not BSL)

- English English (as spoken in England)

- Scots[30]

Insular Celtic

Mixed

Sign languages

Extinct

- Insular Celtic

- Anglic

- Nordic

- Indic

- Romanic

- Kentish Sign

Regional languages and statistics

English

UK speakers, in the 2011 census, 59,824,194 (over the age of three) 98%.

English is a West Germanic language brought around the 5th century CE to the east coast of what is now England by Germanic-speaking immigrants from around present-day northern Germany, who came to be known as the Anglo-Saxons. The fusion of these settlers' dialects became what is now termed Old English: the word English is derived from the name of the Angles. English soon displaced the previously predominant British Celtic and British Latin throughout most of England. It spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria. Following the economic, political, military, scientific, cultural, and colonial influence of Great Britain and the United Kingdom from the 18th century, via the British Empire, and of the United States since the mid-20th century, it has been widely dispersed around the world, and become the leading language of international discourse. Many English words are based on roots from Latin, because Latin in some form was the lingua franca of the Christian Church and of European intellectual life. The language was further influenced by the Old Norse language, with Viking invasions in the 8th and 9th centuries. The Norman conquest of England in the 11th century gave rise to heavy borrowings from Norman French, and vocabulary and spelling conventions began to give what had now become Middle English the superficial appearance of a close relationship with Romance languages. The Great Vowel Shift that began in the south of England in the 15th century is one of the historical events marking the separation of Middle and Modern English.

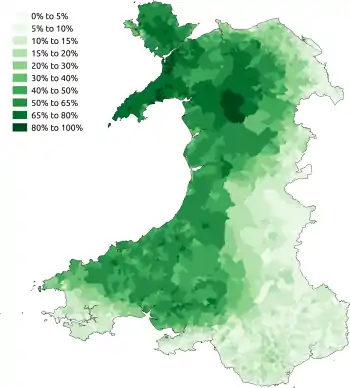

Wales

Welsh (Cymraeg) emerged in the 6th century from Brittonic, the common ancestor of Welsh, Breton, Cornish, and the extinct language known as Cumbric. Welsh is thus a member of the Brythonic branch of the Celtic languages, and is spoken natively in Wales. There are also Welsh speakers in Y Wladfa (The Colony),[34] a Welsh settlement in Argentina, which began in 1865 and is situated mainly along the coast of Chubut Province in the south of Patagonia. Chubut estimates the number of Patagonian Welsh speakers to be about 1,500.

Both the English and Welsh languages have official, but not always equal, status in Wales. English has de facto official status everywhere, whereas Welsh has limited, but still considerable, official, de jure, status in only the public service, the judiciary, and elsewhere as prescribed in legislation. The Welsh language is protected by the Welsh Language Act 1993 and the Government of Wales Act 1998, and since 1998 it has been common, for example, for almost all British Government Departments to provide both printed documentation and official websites in both English and Welsh. On 7 December 2010, the National Assembly for Wales unanimously approved a set of measures to develop the use of the Welsh language within Wales.[35][36] On 9 February 2011, this measure received Royal Assent and was passed, thus making the Welsh language an officially recognised language within Wales.[37]

The Welsh Language Board[38] indicated in 2004 that 553,000 people (19.7% of the population of Wales in households or communal establishments) were able to speak Welsh. Based on an alternative definition, there has been a 0.9 percentage point increase when compared with the 2001 census, and an increase of approximately 35,000 in absolute numbers within Wales. Welsh is therefore a growing language within Wales.[38] Of those 553,000 Welsh speakers, 57% (315,000) were considered by others to be fluent, and 477,000 people consider themselves fluent or "fair" speakers. 62% of speakers (340,000) claimed to speak the language daily, including 88% of fluent speakers.[38]

However, there is some controversy over the actual number who speak Welsh: some statistics include people who have studied Welsh to GCSE standard, many of whom could not be regarded as fluent speakers of the language. Conversely, some first-language speakers may choose not to report themselves as such. These phenomena, also seen with other minority languages outside the UK, make it harder to establish an accurate and unbiased figure for how many people speak it fluently. Furthermore, no question about Welsh language ability was asked in the 2001 census outside Wales, thereby ignoring a considerable population of Welsh speakers – particularly concentrated in neighbouring English counties and in London and other large cities.

Nevertheless, the 2011 census recorded an overall reduction in Welsh speakers, from 582,000 in 2001 to 562,000 in 2011, despite an increase in the size of the population—a 2% drop (from 21% to 19%) in the proportion of Welsh speakers.[39] An estimated 110,000 to 150,000 people in England speak Welsh.[16][40]

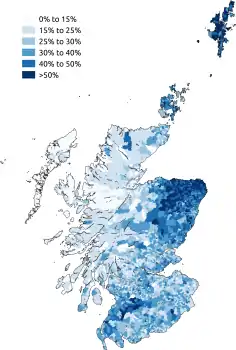

Scotland

Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig)

Scottish Gaelic is a Celtic language native to Scotland. A member of the Goidelic branch of the Celtic languages, Scottish Gaelic, like Modern Irish and Manx, developed out of Middle Irish, and thus descends ultimately from Primitive Irish. Outside Scotland, a dialect of the language known as Canadian Gaelic exists in Canada on Cape Breton Island and isolated areas of the Nova Scotia mainland. This variety has around 2000 speakers, amounting to 1.3% of the population of Cape Breton Island.

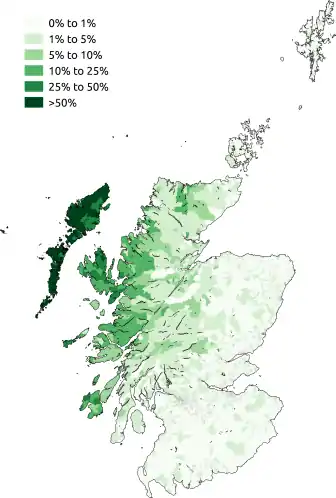

The 2011 census of Scotland showed that a total of 57,375 people (1.1% of the Scottish population aged over three years old) in Scotland could speak Gaelic at that time, with the Outer Hebrides being the main stronghold of the language. The census results indicate a decline of 1,275 Gaelic speakers from 2001. A total of 87,056 people in 2011 reported having some facility with Gaelic compared to 93,282 people in 2001, a decline of 6,226.[41][42] Despite this decline, revival efforts exist and the number of speakers of the language under age 20 has increased.[43]

The Gaelic language was given official recognition for the first time in Scotland in 2005, by the Scottish Parliament's Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005, which aims to promote the Gaelic language to a status "commanding equal respect" with English. However, this wording has no clear meaning in law, and was chosen to prevent the assumption that the Gaelic language is in any way considered to have "equal validity or parity of esteem with English".[44] A major limitation of the act, though, is that it does not constitute any form of recognition for the Gaelic language by the UK government, and UK public bodies operating in Scotland, as reserved bodies, are explicitly exempted from its provisions.[45]

Scots

The Scots language originated from Northumbrian Old English. The Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria stretched from south Yorkshire to the Firth of Forth from where the Scottish elite continued the language shift northwards. Since there are no universally accepted criteria for distinguishing languages from dialects, scholars and other interested parties often disagree about the linguistic, historical and social status of Scots. Although a number of paradigms for distinguishing between languages and dialects do exist, these often render contradictory results. Focused broad Scots is at one end of a bipolar linguistic continuum, with Scottish Standard English at the other. Consequently, Scots is often regarded as one of the ancient varieties of English, but with its own distinct dialects. Alternatively Scots is sometimes treated as a distinct Germanic language, in the way Norwegian is closely linked to, yet distinct from, Danish.

The 2011 UK census was the first to ask residents of Scotland about Scots. A campaign called Aye Can was set up to help individuals answer the question.[46][47] The specific wording used was "Which of these can you do? Tick all that apply" with options for 'Understand', 'Speak', 'Read' and 'Write' in three columns: English, Scottish Gaelic and Scots.[48] Of approximately 5.1 million respondents, about 1.2 million (24%) could speak, read and write Scots, 3.2 million (62%) had no skills in Scots and the remainder had some degree of skill, such as understanding Scots (0.27 million, 5.2%) or being able to speak it but not read or write it (0.18 million, 3.5%).[49] There were also small numbers of Scots speakers recorded in England and Wales on the 2011 Census, with the largest numbers being either in bordering areas (e.g. Carlisle) or in areas that had recruited large numbers of Scottish workers in the past (e.g. Corby or the former mining areas of Kent).[50]

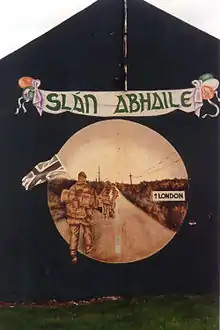

Northern Ireland

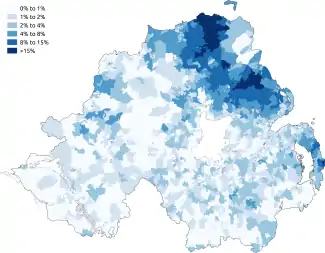

Ulster Scots

2% speak Ulster Scots, seen by some as a language distinct from English and by some as a dialect of English, according to the 1999 Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey (around 30,000 speakers). Some definitions of Ulster Scots may also include Standard English spoken with an Ulster Scots accent. The language was brought to Ireland by Scottish planters from the 16th Century.

Irish (Gaeilge)

Irish was the predominant language of the Irish people for most of their recorded history, and they brought their Gaelic speech with them to other countries, notably Scotland and the Isle of Man where it gave rise to Scottish Gaelic and Manx.

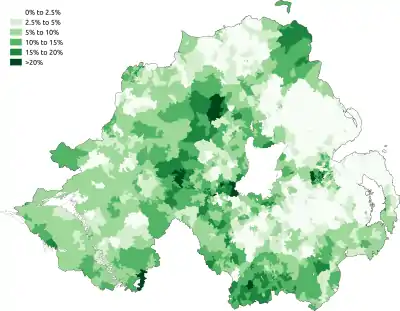

It has been estimated that the active Irish-language scene probably comprises 5 to 10 per cent of Ireland's population.[51] In the 2011 census, 11% of the population of Northern Ireland claimed "some knowledge of Irish"[52] and 3.7% reported being able to "speak, read, write and understand" Irish.[52] In another survey, from 1999, 1% of respondents said they spoke it as their main language at home.[53]

Alongside British Sign Language, Irish Sign Language is also used.

Cornwall

Cornish, a Brythonic Celtic language related to Welsh, was spoken in Cornwall throughout the Middle Ages. Its use began to decline from the 14th century, especially after the Prayer Book Rebellion in 1549. The language continued to function as a first language in Penwith in the far west of Cornwall until the late 18th century, with the last native speaker thought to have died in 1777.[32]

A revival initiated by Henry Jenner began in 1903. In 2002, the Cornish language named as an historical regional language under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.[31][54] The Cornish Language Strategy project commissions research into the Cornish language.

Principal minority language areas

- Welsh: North-West Wales: Percentage of speakers 69% (76% understand Welsh). Population: Gwynedd - 118,400 (2001 census)

- Scottish Gaelic: Outer Hebrides: Percentage of speakers 61%. Population: Na h-Eileanan Siar - 27,400[55] In the 2001 census, each island overall was over 50% Gaelic speaking – South Uist (71%), Harris (69%), Barra (68%), North Uist (67%), Lewis (56%) and Benbecula (56%). With 59.3% of Gaelic speakers or a total of 15,723 speakers, this made the Outer Hebrides the most strongly coherent Gaelic speaking area in Scotland.[56][57]

British Sign Language

British Sign Language, often abbreviated to BSL, is the language of 125,000 Deaf adults, about 0.3%[24] of the total population of the United Kingdom. It is not exclusively the language of Deaf people; many relatives of Deaf people and others can communicate in it fluently. Recognised to be a language by the UK Government on 18 March 2003,[58] BSL has the highest number of monolingual users of any indigenous minority language in the UK.

Second or additional languages

Throughout the UK, many citizens can speak, or at least understand (to a degree where they could have a conversation with someone who speaks that language), a second or even a third language from secondary school education, primary school education or from private classes. 23% of the UK population can speak/understand French, 9% can speak/understand German and 8% can speak/understand Spanish.[8][59]

38% of UK citizens report that they can speak (well enough to have a conversation) at least one language other than their mother tongue, 18% at least two languages and 6% at least three languages. 62% of UK citizens cannot speak any second language.[8] These figures include those who describe their level of ability in the second language as "basic".[8] Due to the dominance of modern English in media and business, English speakers have little exposure to foreign languages and media.

Language teaching is compulsory in all English schools from the ages of 5 or 7. Modern and ancient languages, such as French, German, Spanish, Latin, Greek, Mandarin, Russian, Bengali, Hebrew, and Arabic, are studied.[60] Language teaching is compulsory from the ages of 11 or 12 in Scotland and Wales.

UK census

Abilities in the regional languages of the UK (other than Cornish) for those aged three and above were recorded in the UK census 2011 as follows.[61][62][63]

| Ability | Wales | Scotland | Northern Ireland | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welsh | Scottish Gaelic | Scots | Irish | Ulster-Scots | ||||||

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Understands but does not speak, read or write | 157,792 | 5.15% | 23,357 | 0.46% | 267,412 | 5.22% | 70,501 | 4.06% | 92,040 | 5.30% |

| Speaks, reads and writes | 430,717 | 14.06% | 32,191 | 0.63% | 1,225,622 | 23.95% | 71,996 | 4.15% | 17,228 | 0.99% |

| Speaks but does not read or write | 80,429 | 2.63% | 18,966 | 0.37% | 179,295 | 3.50% | 24,677 | 1.42% | 10,265 | 0.59% |

| Speaks and reads but does not write | 45,524 | 1.49% | 6,218 | 0.12% | 132,709 | 2.59% | 7,414 | 0.43% | 7,801 | 0.45% |

| Reads but does not speak or write | 44,327 | 1.45% | 4,646 | 0.09% | 107,025 | 2.09% | 5,659 | 0.33% | 11,911 | 0.69% |

| Other combination of skills | 40,692 | 1.33% | 1,678 | 0.03% | 17,381 | 0.34% | 4,651 | 0.27% | 959 | 0.06% |

| No skills | 2,263,975 | 73.90% | 5,031,167 | 98.30% | 3,188,779 | 62.30% | 1,550,813 | 89.35% | 1,595,507 | 91.92% |

| Total | 3,063,456 | 100.00% | 5,118,223 | 100.00% | 5,118,223 | 100.00% | 1,735,711 | 100.00% | 1,735,711 | 100.00% |

| Can speak | 562,016 | 18.35% | 57,602 | 1.13% | 1,541,693 | 30.12% | 104,943 | 6.05% | 35,404 | 2.04% |

| Has some ability | 799,481 | 26.10% | 87,056 | 1.70% | 1,929,444 | 37.70% | 184,898 | 10.65% | 140,204 | 8.08% |

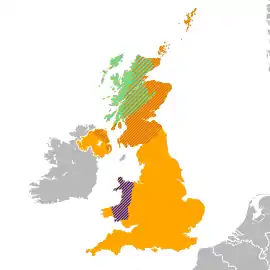

- Distribution of those who stated they could speak a regional language in the 2011 census.

Note: Scale used varies for each map.

Welsh

Welsh Scots

Scots Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic Irish

Irish Ulster-Scots

Ulster-Scots

Status

Certain nations and regions of the UK have frameworks for the promotion of their autochthonous languages.

- In Wales, the Welsh Language Act 1993 requires English and Welsh to be treated equally throughout the public sector. This was further enforced through the passing of the Welsh Language (Wales) Measure 2011.[64][65]

- In Scotland, the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005 gave the Scottish Gaelic language its first statutory basis; and the Western Isles region of Scotland has a policy to promote the language.

- In Northern Ireland, Irish and Ulster Scots enjoy limited use alongside English (mainly in publicly commissioned translations).

The UK government has ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in respect of:

- Cornish (in Cornwall)

- Irish and Ulster Scots (in Northern Ireland)

- Scots and Scottish Gaelic (in Scotland)

- Welsh (in Wales)

Under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (which is not legally enforceable, but which requires states to adopt appropriate legal provision for the use of regional and minority languages) the UK government has committed itself to the recognition of certain regional languages and the promotion of certain linguistic traditions. The UK has ratified[66] for the higher level of protection (Section III) provided for by the Charter in respect of Welsh, Scottish Gaelic and Irish. Cornish, Scots in Scotland and Northern Ireland (in the latter territory officially known as Ulster Scots or Ullans, but in the speech of users simply as Scottish or Scots) are protected by the lower level only (Section II). The UK government has also recognised British Sign Language as a language in its own right[58] of the United Kingdom.

A number of bodies have been established to oversee the promotion of the regional languages: in Scotland, Bòrd na Gàidhlig oversees Scottish Gaelic. Foras na Gaeilge has an all-Ireland remit as a cross-border language body, and Tha Boord o Ulstèr-Scotch is intended to fulfil a similar function for Ulster Scots, although hitherto it has mainly concerned itself with culture. In Wales, the Welsh Language Commissioner (Comisiynydd y Gymraeg) is an independent body established to promote and facilitate use of the Welsh language, mainly by imposing Welsh language standards on organisations.[67] The Cornish Language Partnership is a body that represents the major Cornish language and cultural groups and local government's language needs. It receives funding from the UK government and the European Union, and is the regulator of the language's Standard Written Form, agreed in 2008.

Language versus dialect

There are no universally accepted criteria for distinguishing languages from dialects, although a number of paradigms exist, which give sometimes contradictory results. The distinction is therefore a subjective one, dependent on the user's frame of reference.

Scottish Gaelic and Irish are generally viewed as being languages in their own right rather than dialects of a single tongue, but they are sometimes mutually intelligible to a limited degree – especially between southern dialects of Scottish and northern dialects of Irish (programmes in these two forms of Gaelic are broadcast respectively on BBC Radio nan Gàidheal and RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta), but the relationship between Scots and English is less clear, since there is usually partial mutual intelligibility.

Since there is a very high level of mutual intelligibility between contemporary speakers of Scots in Scotland and in Ulster (Ulster Scots), and a common written form was current well into the 20th century, the two varieties have usually been considered as dialects of a single tongue rather than languages in their own right; the written forms have diverged in the 21st century. The government of the United Kingdom "recognises that Scots and Ulster Scots meet the Charter's definition of a regional or minority language".[66] Whether this implies recognition of one regional or minority language or two is a question of interpretation. Ulster Scots is defined in legislation (The North/South Co-operation (Implementation Bodies) Northern Ireland Order 1999) as: the variety of the Scots language which has traditionally been used in parts of Northern Ireland and in Donegal in Ireland.[68]

While in continental Europe closely related languages and dialects may get official recognition and support, in the UK there is a tendency to view closely related vernaculars as a single language. Even British Sign Language is mistakenly thought of as a form of 'English' by some, rather than as a language in its own right, with a distinct grammar and vocabulary. The boundaries are not always clear cut, which makes it hard to estimate numbers of speakers.

Hostility

In Northern Ireland, the use of Irish and Ulster Scots is sometimes viewed as politically loaded, despite both having been used by all communities in the past. According to the Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey 1999, the ratio of Unionist to Nationalist users of Ulster Scots is 2:1. About 1% of Catholics claim to speak it, while 2% of Protestants claim to speak it. The disparity in the ratios as determined by political and faith community, despite the very large overlap between the two, reflects the very low numbers of respondents.[69] Across the two communities 0% speak it as their main language at home.[70] A 2:1 ratio would not differ markedly from that among the general population in those areas of Northern Ireland where Scots is spoken.

Often the use of the Irish language in Northern Ireland has met with the considerable suspicion of Unionists, who have associated it with the largely Catholic Republic of Ireland, and more recently, with the republican movement in Northern Ireland itself. Catholic areas of Belfast have street signs in Irish similar to those in the Republic. Approximately 14% of the population speak Irish,[71] however only 1% speak it as their main language at home.[70] Under the St Andrews Agreement, the British government committed itself to introducing an Irish Language Act, and it was hoped that a consultation period ending on 2 March 2007 could see Irish becoming an official language, having equal validity with English, recognised as an indigenous language, or aspire to become an official language in the future.[72] However, with the restoration of the Northern Ireland Assembly in May 2007, responsibility for this was passed to the Assembly, and the commitment was promptly broken. In October 2007, the then Minister of Culture, Arts and Leisure, Edwin Poots MLA, announced to the assembly that no Irish Language Act would be brought forward. As of April 2016, no Irish Language Act applying to Northern Ireland has been passed, and none is currently planned.

Some resent Scottish Gaelic being promoted in the Lowlands. Gaelic place names are relatively rare in the extreme south-east (that part of Scotland which had previously been under Northumbrian rule)[73] and the extreme north-east (part of Caithness, where Norse was previously spoken).[74]

Two areas with mostly Norse-derived placenames (and some Pictish), the Northern Isles (Shetland and Orkney) were ceded to Scotland in lieu of an unpaid dowry in 1472, and never spoke Gaelic; its traditional vernacular Norn, a derivative of Old Norse mutually intelligible with Icelandic and Faroese, died out in the 18th century after large-scale immigration by Lowland Scots speakers. To this day, many Shetlanders and Orcadians maintain a separate identity, albeit through the Shetland and Orcadian dialects of Lowland Scots, rather than their former tongue. Norn was also spoken at one point in Caithness, apparently dying out much earlier than Shetland and Orkney. However, the Norse speaking population were entirely assimilated by the Gaelic speaking population in the Western Isles; to what degree this happened in Caithness is a matter of controversy, although Gaelic was spoken in parts of the county until the 20th century.

Non-recognition

Scots within Scotland and the regional varieties of English within England receive little or no official recognition. The dialects of northern England share some features with Scots that those of southern England do not. The regional dialects of England were once extremely varied, as is recorded in Joseph Wright's English Dialect Dictionary and the Survey of English Dialects, but they have died out over time so that regional differences are now largely in pronunciation rather than in grammar or vocabulary.

Public funding of minority languages continues to produce mixed reactions, and there is sometimes resistance to their teaching in schools. Partly as a result, proficiency in languages other than "Standard" English can vary widely.

Immigrant languages

Communities migrating to the UK in recent decades have brought many more languages to the country. Surveys started in 1979 by the Inner London Education Authority discovered over 100 languages being spoken domestically by the families of the inner city's school children.

British Asians speak dozens of different languages, and it is difficult to determine how many people speak each language alongside English. The largest subgroup of British Asians are those of Punjabi origin (representing approximately two thirds of direct migrants from South Asia to the UK), from both India and Pakistan, they number over 2 million in the UK and are the largest Punjabi community outside of South Asia.[75] The Punjabi language is currently the third most spoken language in the UK. Many Black Britons speak English as their first language. Their ancestors mostly came from the West Indies, particularly Jamaica, and generally also spoke English-based creole languages,[76] hence there are significant numbers of Caribbean creole speakers (see below for Ethnologue figures). With over 300,000 French-born people in the UK, plus the general popularity of the language, French is understood by 23% of the country's population. A large proportion of the Black British population, especially African-born immigrants speak French as a first or second language.

Sylheti, a language closely related to Bengali (sometimes viewed as a dialect of Bengali), is the most spoken language variety of the British Bangladeshis with around 400,000 speakers.[77] Standard Bengali is spoken by a minority of British Bangladeshis and majority of West Bengalis. Sylheti currently is mainly a spoken language lacking a standardised written form, children are therefore encouraged to learn standard Bengali.[78] Though not recognised as a language officially in Bangladesh or India, it is recognised as part of the list of native languages spoken by students in British schools.[79] While some institutions such as the National Health Service (NHS), provide Sylheti translation services.[80]

Most common immigrant languages

According to the 2011 census, English or Welsh was the main language of 92.3% of the residents of England and Wales. Among other languages, the most common were as follows.[81]

- Polish 546,000 or 1.0%

- Punjabi 273,000 or 0.5%

- Urdu 269,000 or 0.5%

- Bengali (with Sylheti and Chittagonian) 221,000 or 0.4%

- Gujarati 213,000 or 0.4%

- Arabic 159,000 or 0.3%

- French 147,000 or 0.3%

- Chinese 141,000 or 0.3%

- Portuguese 133,000 or 0.2%

- Spanish 120,000 or 0.2%

- Tamil 101,000 or 0.2%

- Turkish 99,000 or 0.2%

- Italian 92,000 or 0.2%

- Somali 86,000 or 0.2%

- Lithuanian 85,000 or 0.2%

- German 77,000 or 0.1%

- Persian 76,000 or 0.1%

- Philippine languages (with Tagalog and Cebuano) 70,000 or 0.1%

- Romanian 68,000 or 0.1%

Norman French and Latin

Norman French is still used in the Houses of Parliament for certain official business between the clerks of the House of Commons and the House of Lords, and on other official occasions such as the dissolution of Parliament.

Latin is also used to a limited degree in certain official mottoes, for example Nemo me impune lacessit, legal terminology (habeas corpus), and various ceremonial contexts. Latin abbreviations can also be seen on British coins. The use of Latin has declined greatly in recent years. However, the Catholic Church retains Latin in official and quasi-official contexts. Latin remains the language of the Roman Rite, and the Tridentine Mass is celebrated in Latin. Although the Mass of Paul VI is usually celebrated in English, it can be and often is said in Latin, in part or whole, especially at multilingual gatherings. It is the official language of the Holy See, the primary language of its public journal, the Acta Apostolicae Sedis, and the working language of the Roman Rota.[82]

At one time, Latin and Greek were commonly taught in British schools (and were required for entrance to the ancient universities until 1919, for Greek, and the 1960s, for Latin[83]), and A-Levels and Highers are still available in both subjects.

Languages of the Channel Islands and Isle of Man

The Isle of Man and the Bailiwicks of Guernsey and Jersey are not part of the UK, but are closely associated with it, being British Crown Dependencies.

For the insular forms of English, see Manx English (Anglo-Manx), Guernsey English and Jersey English. Forms of French are, or have been, used as an official language in the Channel Islands, e.g. Jersey Legal French.

The indigenous languages of the Crown dependencies are recognised as regional languages by the British and Irish governments within the framework of the British-Irish Council.

Guernsey

Guernésiais, a form of French spoken on Guernsey, is related to Norman, and Oïl languages. 14% of the population claim some understanding of the language.

There is intercomprehension (with some difficulty) with Jèrriais-speakers from Jersey and Norman-speakers from mainland Normandy. Guernésiais most closely resembles the Norman dialect of La Hague in the Cotentin Peninsula (Cotentinais). The creation of a Guernsey Language Commission was announced on 7 February 2013[84] as an initiative by government to preserve the linguistic culture. The Commission has operated since Liberation Day, 9 May 2013.

Jersey

Jèrriais, a form of French spoken on Jersey, is related to Norman and Oïl languages.

Although Jèrriais is now the first language of a very small minority, until the 19th century it was the everyday language of the majority of the population, and even until the Second World War up to half the population could communicate in the language. The use of Jèrriais is also to be noted during the German occupation of the Channel Islands during the Second World War; the local population used Jèrriais among themselves as a language neither the occupying Germans, nor their French interpreters, could understand. However, the social and economic upheaval of the War meant that use of English increased dramatically after the Liberation. It is considered that the last monolingual adult speakers probably died in the 1950s, although monolingual speaking children were being received into schools in St. Ouen as late as the late 1970s.

The Sercquiais dialect of Sark is descended from Jèrriais, but is not recognised under this framework and the last native speaker died in 2004. Auregnais, the Norman dialect of Alderney, is now extinct.

Isle of Man

The Manx began to diverge from Early Modern Irish in around the 13th century and from Scottish Gaelic in the 15th. The language sharply declined during the 19th century and was supplanted by English. The UK government has ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages on behalf of the Manx government.

Although only a small minority of the Isle of Man's population is fluent in the language, a larger minority has some knowledge of it. Manx is widely considered to be an important part of the island's culture and heritage. Although the last surviving native speaker of the Manx language, Ned Maddrell, died in 1974, the language has never fallen completely out of use. Manx has been the subject of language revival efforts, so that despite the small number of speakers, Manx has become more visible on the island, with increased signage, radio broadcasts and a Manx-medium primary school. The revival of Manx has been aided by the fact that the language was well recorded; for example, the Bible was translated into Manx, and audio recordings were made of native speakers. Its similarity to Irish has also helped its reconstruction. In the 2011 census, 1,823 out of 80,398, or 2.27% of the population, claimed to have knowledge of Manx.[85] This is an increase of 134 people from the 2001 census.[86]

Extinct British languages

Cornish

Cornish became extinct as a first language in the late 18th century with the last native speaker thought to have died in 1777.[32] Its cultural legacy has continued within Cornwall.[33]

Norn

A North Germanic once spoken in the Shetland Islands, Orkney Islands and Caithness. It is likely that the language was dying out in the late 18th century, with the reports putting the last Norn speakers in the 19th century.[87] Walter Sutherland from Skaw in Unst, who died about 1850, has been cited as the last native speaker of the Norn language. The remote islands of Foula and Unst are variously claimed as the last refuges of the language in Shetland, where there were people "who could repeat sentences in Norn, probably passages from folk songs or poems, as late as 1893".[88] Fragments of vocabulary survived the death of the main language and remain to this day, mainly in place-names and terms referring to plants, animals, weather, mood, and fishing vocabulary.

Kentish Sign

Unrelated to both the Banzsl British Sign Language and Northern Irish SL and the Francosign Irish SL, the sign language spoken in Kent was a unique village sign language that went to sleep and was superseded by BSL in the 17th century. There are fairly weak rumours that Martha's Vineyard Sign Language (one of ASL's substrate languages) descended through Kentish signers, though proper evidence has not yet been substantiated.

Pictish

Pictish was probably a Brittonic language, or dialect, spoken by the Picts, the people of northern and central Scotland in the Early Middle Ages, which became extinct c.900 AD. There is virtually no direct attestation of Pictish, short of a limited number of geographical and personal names found on monuments and the contemporary records in the area controlled by the Kingdom of the Picts. Such evidence, however, points to the language being closely related to the Brittonic language spoken prior to Anglo-Saxon settlement in what is now southern Scotland, England and Wales. A minority view held by a few scholars claims that Pictish was at least partially non-Indo-European or that a non-Indo-European and Brittonic language coexisted.

Cumbric

Cumbric' was a variety of the Common Brittonic language spoken during the Early Middle Ages in the Hen Ogledd or "Old North" in what is now Northern England and southern Lowland Scotland.[89] It was closely related to Old Welsh and the other Brittonic languages. Place name evidence suggests Cumbric speakers may have carried it into other parts of northern England as migrants from its core area further north.[90] It may also have been spoken as far south as Pendle and the Yorkshire Dales. Most linguists think that it became extinct in the 12th century, after the incorporation of the semi-independent Kingdom of Strathclyde into the Kingdom of Scotland.

See also

- British Overseas Territories#Languages

- Literature in the other languages of Britain

- Regional accents of English speakers

- British English

- British literature

- Languages of the European Union

- European languages

- Celtic languages

- History of the Scots language

- Gaelic road signs in Scotland

- Beurla Reagaird

- Polari

- Pidgin English

References

- According to the 2011 census, 53,098,301 people in England and Wales, 5,044,683 people in Scotland, and 1,681,210 people in Northern Ireland can speak English "well" or "very well"; totalling 59,824,194. Therefore, out of the 60,815,385 residents of the UK over the age of three, 98% claim they can speak English "well" or "very well".

- "United Kingdom". Languages Across Europe. BBC. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "United Kingdom; Key Facts". Commonwealth Secretariat. Retrieved 23 April 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "English language". Directgov. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- Scotland's Census 2011 – Language, All people aged 3 and over. Out of the 60,815,385 residents of the UK over the age of three, 1,541,693 (2.5%) can speak Scots, link.

- , Annual Population Survey - Ability to speak Welsh by local authority and year. Out of the 3,021,300 residents of Wales over the age of three, 874,600 (29%) can speak Welsh. Retrieved 02 February 2020.

- Anorak, Scots. "Ulster Scots in the Northern Ireland Census". Scots Language Centre. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- Europeans and their languages (PDF), European Commission, 2006, p. 13, retrieved 5 July 2008

- "BSL Statistics". Sign Language Week. British Deaf Association. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "Home". Cambridge University Press.

- "Language in England and Wales - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- Scotland's Census 2011 – Proficiency in English, All people aged 3 and over.

- Northern Ireland Census 2011 – Main language and Proficiency in English, All usual residents aged 3 and over.

- ONS census, QS205EW – Proficiency in English. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- "Language in England and Wales: 2011". Office for National Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- Bwrdd yr Iaith Gymraeg, A statistical overview of the Welsh language, by Hywel M Jones, page 115, 13.5.1.6, England. Published February 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- "Welsh Language (Wales) Measure 2011". legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- "Welsh Language Measure receives Royal Assent". Welsh Government. 11 February 2011. Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- A.J. Aitken in The Oxford Companion to the English Language, Oxford University Press 1992. p.894

- Scotland's Census 2011 – Language, All people aged 3 and over. Out of the 5,118,223 residents of Scotland over the age of three, 1,541,693 (30%) can speak Scots.

- Annual Population Survey - Ability to speak Welsh by local authority and year. Archived 20 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine Out of the 3,021,300 residents of Wales over the age of three, 874,600 (29%) can speak Welsh. Retrieved 02 February 2020.

- "Annual Population Survey - Ability to read, write and understand spoken Welsh by age, sex and year". gov.wales. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "2011 Census, Key Statistics and Quick Statistics for Wards and Output Areas in England and Wales". Office for National Statistics. 30 January 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "The GP Patient Survey in Northern Ireland 2009/10 Summary Report" (PDF). Department of Health, Social Services, and Public Safety. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "United Kingdom". Ethnologue. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "Angloromani". Ethnologue. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "Scotland's Census 2011: Gaelic report (Part 1)". National Records of Scotland. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- "South West". TeachingEnglish. BBC British Council. 2010. Archived from the original on 8 January 2010. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- "Shelta". Ethnologue. 19 February 1999. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- "List of declarations made with respect to treaty No. 148". European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Council of Europe. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

The United Kingdom declares, in accordance with Article 2, paragraph 1 of the Charter that it recognises that Scots and Ulster Scots meet the Charter's definition of a regional or minority language for the purposes of Part II of the Charter.

- "List of declarations made with respect to treaty No. 148". European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Council of Europe. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

The United Kingdom declares, in accordance with Article 2, paragraph 1, of the Charter that it recognises that Cornish meets the Charter's definition of a regional or minority language for the purposes of Part II of the Charter.

- "THE HISTORY OF THE CORNISH LANGUAGE". CelticLife International. CelticLife International. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- "Cornish Language and Place Names in Cornwall". intoCornwall.com. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- National Library of Wales' bibliography for 'The Welsh settlement in Patagonia'

- "Policy and legislation". Welsh Language. Welsh Government. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "'Historic' assembly vote for new Welsh language law". BBC News. 7 December 2010. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "Welsh Language (Wales) Measure 2011". National Assembly for Wales. Archived from the original on 21 January 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- "2004 Welsh Language Use Survey: the report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 December 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Number of Welsh speakers falling". Bbc.co.uk. 11 December 2012.

- "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - United Kingdom : Welsh". Minority Rights Group International. 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- 2011 Census of Scotland, Table QS211SC. Viewed 30 May 2014.

- Scotland's Census Results Online (SCROL) Archived 11 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Table UV12. Viewed 30 May 2014.

- Scottish Government, "A’ fàs le Gàidhlig", 26 September 2013. Viewed 30 May 2014.

- McLeod, Wilson. "Gaelic in contemporary Scotland: contradictions, challenges and strategies". University of Edinburgh: 7. Retrieved 28 December 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005 (s.10)". Office of Public Sector Information. 1 June 2005. Archived from the original on 7 September 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- "Scottish Census Day 2011 survey begins". BBC News. 26 March 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- "Scots language – Scottish Census 2011". Aye Can. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- "How to fill in your questionnaire: Individual question 16". Scotland's Census. General Register Office for Scotland. Archived from the original on 12 October 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- "Scotland's Census 2011: Standard Outputs". National Records of Scotland. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- "2011 Census: KS206EW Household language, local authorities in England and Wales (Excel sheet 268Kb)".

- Romaine, Suzanne (2008), "Irish in a Global Context", in Caoilfhionn Nic Pháidín and Seán Ó Cearnaigh (ed.), A New View of the Irish Language, Dublin: Cois Life Teoranta, ISBN 978-1-901176-82-7

- Census 2011

- Northern Ireland LIFE & TIMES Survey: What is the main language spoken in your own home?

- "Cornish gains official recognition". BBC News. 6 November 2002. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- "Mid-2013 Population Estimates Scotland". gro-scotland.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2004) 1901–2001 Gaelic in the Census (PowerPoint) Linguae Celticae. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- "Census 2001 Scotland: Gaelic speakers by council area" Comunn na Gàidhlig. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- "Written Ministerial Statements". Bound Volume Hansard – Written Ministerial Statements. House of Commons. 18 March 2003. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "Which languages the UK needs most and why" (PDF).

- https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/239042/PRIMARY_national_curriculum_-_Languages.pdf

- "NOMIS – Census 2011". Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- "Scotland's Census 2011 – Standard Outputs". Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- "Northern Ireland Neighbourhood Information Service". Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- "Mesur y Gymraeg (Cymru) 2011" (in Welsh). UK Legislation. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "Welsh Language (Wales) Measure 2011". UK Legislation. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- List of declarations made with respect to treaty No. 148, European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, Status as of: 17 March 2011

- "Comisiynydd y Gymraeg - Aim of the Welsh Language Commissioner". Comisiynyddygymraeg.cymru. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- "Initial Periodical Report by the United Kingdom presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in accordance with Article 15 of the Charter". European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Council of Europe. 1 July 2002. Archived from the original on 14 May 2005. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "1999 Community Relations". Northern Ireland Life & Times. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "1999 Community Relations MAINLANG". Northern Ireland Life & Times. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "1990 Community Relations USPKIRSH". Northern Ireland Life & Times. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "Irish language future is raised". BBC News. 13 December 2006. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- Michael Lynch, ed. (2001). The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford University Press. (p.482)

- Viking revaluations : Viking Society Centenary Symposium 14-15 May 1992. Viking Society for Northern Research. 1993. p. 78. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.683.8845. ISBN 9780903521284.

- Ballard, Roger (1994). Desh Pardesh: The South Asian Presence in Britain. C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd. ISBN 1850650918.

- Bagley, Christopher (1979). "A Comparative Perspective on the Education of Black Children in Britain" (PDF). Comparative Education. 15 (1): 63–81. doi:10.1080/0305006790150107.

- Comanaru, Ruxandra; D'Ardenne, Jo (2018). The Development of Research Programme to Translate and Test the Personal well-being Questions in Sylheti and Urdu. pp.16. Köln: GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften. Retrieved on 30 June 2020.

- Achievement of Bangladeshi heritage pupils (PDF). Ofsted. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- British schools enlist Sylheti in their syllabi Dhaka Tribune. 12 July 2017. Retrieved on 10 August 2020.

- Simard, Candide; Dopierala, Sarah M; Thaut, E Marie (2020). "Introducing the Sylheti language and its speakers, and the SOAS Sylheti project" (PDF). Language Documentation and Description. 18: 10. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- "2011 Census: Quick Statistics". Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- Moore, Malcolm (28 January 2007). "Pope's Latinist pronounces death of a language". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- "Bryn Mawr Classical Review 98.6.16". Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- "Language commission to be formed". Guernsey Press. 8 February 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- Isle of Man Census Report 2011 Archived 8 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- "Manx Gaelic revival 'impressive'". BBC News. 22 September 2005. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- Glanville Price, The Languages of Britain (London: Edward Arnold 1984, ISBN 978-0-7131-6452-7), p. 203

- Price (1984), p. 204

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: a historical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 515–516. ISBN 9781851094400.

- James, A. G. (2008): 'A Cumbric Diaspora?' in Padel and Parsons (eds.) A Commodity of Good Names: essays in honour of Margaret Gelling, Shaun Tyas: Stamford, pp. 187–203.

External links

- Sounds Familiar? — Listen to examples of regional accents and dialects across the UK on the British Library's 'Sounds Familiar' website (uses Windows Media Player for content)

Further reading

- Trudgill, Peter (ed.), Language in the British Isles, Cambridge University Press, 1984, ISBN 0-521-28409-0