Miss O'Dell

"Miss O'Dell" is a song by English musician George Harrison, released as the B-side of his 1973 hit single "Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth)". Like Leon Russell's "Pisces Apple Lady", it was inspired by Chris O'Dell, a former Apple employee, and variously assistant and facilitator to musical acts such as the Beatles, Derek & the Dominos, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan and Santana. Harrison wrote the song in Los Angeles in April 1971 while waiting for O'Dell to pay him a visit at his rented home. As well as reflecting her failure to keep the appointment, the lyrics provide a light-hearted insight into the Los Angeles music scene and comment on the growing crisis in East Pakistan that led Harrison to stage the Concert for Bangladesh in August that year.

| "Miss O'Dell" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by George Harrison | ||||

| A-side | "Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth)" | |||

| Released | 7 May 1973 | |||

| Recorded | October 1972–February 1973 Apple Studio, London; FPSHOT, Oxfordshire | |||

| Genre | Folk rock | |||

| Length | 2:33 | |||

| Label | Apple | |||

| Songwriter(s) | George Harrison | |||

| Producer(s) | George Harrison | |||

| George Harrison singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

Harrison recorded "Miss O'Dell" in England between October 1972 and February 1973, during the sessions for his Living in the Material World album. The arrangement reflects the influence of Dylan, and the recording is notable for Harrison breaking into laughter midway through the verses. A popular B-side, "Miss O'Dell" was unavailable officially for over 30 years after this initial release, until its inclusion as a bonus track on the 2006 reissue of Material World. An alternate, laughter-free vocal take of the song circulates on Harrison bootleg CDs and was included on the DVD accompanying the deluxe edition of Living in the Material World in 2006. O'Dell named her 2009 autobiography after the song.

Background and composition

After arriving in London from Los Angeles in mid May 1968, to start work at the Beatles' Apple Corps headquarters at the invitation of her friend Derek Taylor,[1] Chris O'Dell began a career that saw her become, in author Philip Norman's words, "the ultimate insider" in rock-music circles.[2] In the space of two years, O'Dell witnessed first-hand a series of key moments in rock 'n' roll: she joined in the backing chorus on the song "Hey Jude"; she was on the Apple rooftop in January 1969 when the Beatles played live for the last time; she personally delivered the harmonicas for Bob Dylan's comeback performance at the Isle of Wight; and on the day Paul McCartney announced he was leaving the Beatles, she was there at George Harrison's Friar Park mansion when Harrison and John Lennon met to discuss the news.[3] Later in the 1970s, O'Dell went on to work with the Rolling Stones, during the LA sessions for Exile on Main St. (1972) and their subsequent "STP" US tour, and on Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young's 1974 reunion tour and Dylan's Rolling Thunder Revue of 1975, but said her time with the Stones, she says, felt like a "climb down the ladder".[4] Similarly, after working for Harrison and his wife Pattie Boyd during their first few months at Friar Park, from March to June 1970, she would always view the Henley estate as a spiritual home,[5] and the Harrisons as her most important friends in the fickle world of the music business.[6] O'Dell assisted Harrison in preparing for the recording sessions for All Things Must Pass (1970), helped him recruit musicians for the Bangladesh benefit concerts, served on his 1974 North American tour with Ravi Shankar, and was privy to the details that ended the Harrisons' marriage as well as that of Ringo Starr and Maureen Starkey.[7]

By April 1971, O'Dell was back in California, working with former Apple Records A&R manager Peter Asher on developing the careers of singer-songwriters such as James Taylor, Carole King and Linda Ronstadt.[8] At the same time, Harrison, having recently contributed to the debut solo album by Bobby Whitlock, formerly of Derek & the Dominos, and finished the Radha Krishna Temple (London) album[9][10] – both acts that O'Dell had been involved with professionally in 1969–70 – was now in Los Angeles to begin work on Shankar's Raga film soundtrack.[11][12] He had also been informed of the tragic events occurring in Shankar's homeland, following the Bhola cyclone and the outbreak of the Bangladesh Liberation War.[13][14] This was an issue that Harrison dealt with in the opening verse of a song he began writing, "Miss O'Dell",[15] while waiting for his eponymous friend to visit him at his rented Malibu home:[11][16]

I'm the only one down here who's got

Nothing to say about the war or the rice

That keeps going astray on its way to Bombay ...

Adopting a considerably more lighthearted approach than would be the case in his "storming, urgent" song "Bangla Desh" a couple of months later,[17] these lines refer to international donations of rice, which "somehow" ended up becoming the property of the Indian Government instead and either being sold in government shops in India, or getting exported back to the West to be sold in Indian shops there.[18] ("Very strange," he concludes in his autobiography.[18])

His disenchantment with the Californian surroundings and O'Dell's failure to turn up as arranged[19] are reflected in the next lines:[20]

That smog that keeps polluting up our shores

Is boring me to tears

Why don't you call me, Miss O'Dell?

In verse two, Harrison describes the ocean-front house, the balcony of which stretched out over the waves below:[11]

I'm the only one down here who's got

Nothing to fear from the waves or the night

That keeps rolling on right up to my front porch ...

Inside the house, neither he nor his driver Ben could get the record player to work,[11] and Harrison admits to his absent friend over the song's middle eight: "I can tell you, nothing new / Has happened since I last saw you."[20]

In her 2009 memoir, O'Dell explains that her escalating drug habit had been responsible for her non-attendance on the evening in question, as well as a reluctance to have to put up with scores of hangers-on around the ex-Beatle.[21] In the song's third verse, however, Harrison shows that he too had no interest in the typical trappings of the LA music scene:[20]

I'm the only one down here who's got

Nothing to say about the hip or the dope

Or the cat with most hope to fill the Fillmore

That pushed-and-shoving ringing on my bell

Is not for me tonight

Why don't you call me, Miss O'Dell?

O'Dell eventually drove up the Pacific Coast Highway to Malibu and found him, in keeping with the song's "I'm the only one down here" refrain, alone and feeling "pretty lonely".[14] After joking to her "I'm going to make you famous", Harrison played the new song, about which O'Dell would later write: "I heard George sing 'Miss O'Dell' many times in the years to come, but it would never sound as good as it did that night with the waves breaking and the breeze blowing through the room ..."[22]

Recording

Following the completion of the Rolling Stones' North American tour in late July 1972,[23] a "[d]ead tired and strung out" O'Dell visited Friar Park and found Harrison "happy" and enthusiastic[24] about the music he would soon record for his much-anticipated follow-up to All Things Must Pass.[25] "I remember thinking that this was the old George", O'Dell later wrote, "the fun, light, mischievous George I remembered from my first days at Apple, almost as if the Bangladesh concert had released him from the woes of the past."[24] The same good humour is evident in the performance of "Miss O'Dell",[26][27] which Harrison recorded during the Living in the Material World album sessions, beginning in early October.[28] Musical biographer Simon Leng describes the performance as Harrison in "'Apple Scruffs' busking mode", referring to his Dylan-influenced 1970 tribute song to the Beatles' diehard fans known as Apple scruffs.[29] In early January 1973, Dylan was another guest at Friar Park, along with his wife Sara Lownds.[30] The couple had temporarily escaped a chaotic location shoot in Durango, Mexico, where Dylan was starring in the Sam Peckinpah western Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid.[31]

On the recording of "Miss O'Dell", Harrison plays acoustic guitar and harmonicas,[20] backed by just the rhythm section of Klaus Voormann and Jim Keltner.[32] With its unusually sparse backing, on which Keltner's cowbell is a prominent feature,[20] the released version of "Miss O'Dell" is notable for the three occasions when Harrison bursts into laughter midway through the verses.[33][34] Among the music industry in-jokes contained in the lyrics,[35] Harrison concludes the song by leaving a phone number – that of Paul McCartney's old home in Liverpool.[26] The two former Beatles were still not on good terms following the band's break-up in April 1970,[36] and Harrison's gesture was an example of him "pok[ing] fun" at McCartney, author Bruce Spizer writes.[37] Another example was Harrison's adoption of a similar logo to Wings' for his fictitious "Jim Keltner Fan Club" banner, on the back of the Material World album cover.[38][39] Harrison recorded a "straight" vocal on the same backing track, a version that is available unofficially on bootlegs such as Living in the Alternate World and Pirate Songs.[26]

Release

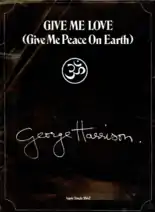

Apple Records released "Miss O'Dell" as the B-side of Living in the Material World's lead single, "Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth)",[40] on 7 May 1973 in America and 25 May in Britain.[41] Authors Chip Madinger and Mark Easter suggest that the song was considered for inclusion on the album also, in its non-laughing vocal take; an alleged early alternative to the LP's side-one track order omitted the album opener, "Give Me Love", and had "Miss O'Dell" closing the side.[42]

As with the majority of the songs on Living in the Material World,[43] the copyright for "Miss O'Dell" was assigned to the Material World Charitable Foundation.[44] Harrison established the foundation in April 1973,[45] partly to support charitable causes,[46] and as a means to avoid the government and legal interference that had resulted in the withholding of funds raised for the Bangladeshi refugees over 1971–72.[47][48][49]

Reissue

Having become a sought-after rarity for over 30 years,[34] "Miss O'Dell" was finally given a second release when included as a bonus track on the 2006 remaster of Living in the Material World.[50][51] The "straight"-vocal take of the song was issued at this time as well, set to archival footage and included on the deluxe-edition, CD/DVD version of the album.[52]

"Miss O'Dell" also appears on the 2014 Apple Years 1968–75 reissue of Material World.[53] The DVD exclusive to the Apple Years box set similarly includes the film clip originally issued in 2006.[54]

Reception

Writing for AllMusic, Bruce Eder considers "Miss O'Dell" to be an "important bonus track" on the remastered Living in the Material World CD, as well as "an exuberant and richly produced, light-hearted number".[55] In another review of the 2006 reissue, for the Vintage Rock website, Shawn Perry viewed the inclusion of "Miss O'Dell" as "unremarkable yet special enough to thrill the hardcore fans". Perry described the film accompanying the alternative take as "a still photo slideshow of Harrison and his pals eating, drinking, and frolicking on the grounds of what may or may not be Friar Park, the former Beatle's estate", and admired the bonus DVD as perhaps the "pièce de résistance" of the deluxe edition of Material World.[56]

The song has traditionally received a warm reception from Beatles biographers. Simon Leng describes it as a "jaunty, Dylanesque flip side", a "short musical postcard" from an ex-Beatle "[sent] off to rock star exile in Los Angeles" and obviously bored with what he finds there.[20] Bruce Spizer views it a "delightful throw-away song perfect for a B-side",[33] while to Chip Madinger and Mark Easter, less impressed with the Material World album, "Miss O'Dell" is a "great track, full of the humor so desperately missing from the rest of the LP".[42]

Theologian Dale Allison describes it as "enigmatic", a "biting exposé" of Harrison's own celebrity status, reflecting the same "ennui" that would later inspire his Traveling Wilburys song "Heading for the Light".[57] Like Madinger and Easter, Ian Inglis welcomes the "spontaneous fun" evident in this "impromptu" recording, compared with Harrison's more "solemn" 1973 album, and recognises the influence of both Basement Tapes-era Bob Dylan & the Band as well as Lonnie Donegan's mid-1950s brand of skiffle.[58] Inglis describes the song as Harrison's "playful and lighthearted tribute" to his and O'Dell's friendship and groups the track within a subcategory of Harrison compositions that "express his fondness" for family and friends.[59] Other examples include "Behind That Locked Door", written to Dylan; "Deep Blue", mourning the death of his mother; and "Unknown Delight", written shortly after the birth of his son, Dhani Harrison.[60]

Personnel

- George Harrison – vocals, acoustic guitar, harmonicas

- Klaus Voorman – bass

- Jim Keltner – drums, cowbell, shaker

References

- O'Dell, pp. 15, 17.

- Philip Norman, dust-jacket quote in O'Dell.

- O'Dell, pp. 54–56, 74–77, 155.

- O'Dell, p. 214.

- O'Dell, pp. 188, 233.

- O'Dell, pp. 161, 162, 185, 188, 193, 214.

- O'Dell, pp. 156, 172–73, 196–98, 257–66, 302, 305–06.

- O'Dell, pp. 182–83.

- Leng, p. 123.

- Castleman & Podrazik, p. 101.

- Harrison, p. 248.

- Lavezzoli, p. 187.

- Leng, p. 111.

- O'Dell, p. 189.

- Len Comaratta, "Dusting 'Em Off: George Harrison and Friends – The Concert For Bangladesh", Consequence of Sound, 29 December 2012 (archived version retrieved 15 August 2014).

- Clayson, p. 317.

- Leng, p. 113.

- Harrison, p. 220.

- O'Dell, pp. 186–88.

- Leng, p. 136.

- O'Dell, p. 186.

- O'Dell, p. 191.

- Wyman, p. 398.

- O'Dell, p. 234.

- Schaffner, p. 159.

- Madinger & Easter, p. 442.

- Inglis, pp. 43, 44.

- Badman, p. 83.

- Leng, pp. 94, 136.

- Sounes, p. 272.

- Heylin, pp. 342–44.

- Inglis, p. 43.

- Spizer, p. 250.

- Huntley, p. 95.

- Clayson, p. 322.

- Doggett, pp. 180, 193.

- Spizer, pp. 250, 256.

- Rodriguez, p. 81.

- Spizer, pp. 158, 256.

- Badman, p. 99.

- Castleman & Podrazik, p. 125.

- Madinger & Easter, p. 440.

- Schaffner, p. 160.

- Harrison, p. 385.

- Badman, p. 98.

- Book accompanying Collaborations box set by Ravi Shankar and George Harrison (Dark Horse Records, 2010; produced by Olivia Harrison; package design by Drew Lorimer & Olivia Harrison), p. 32.

- Clayson, pp. 315–16.

- Michael Gross, "George Harrison: How Dark Horse Whipped Up a Winning Tour", CIrcus Raves, March 1975; available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- "At the Starting Gate", Contra Band Music, 21 August 2012 (retrieved 22 October 2013).

- "George Harrison Living in the Material World (Bonus Tracks)" > Tracks, AllMusic (retrieved 4 June 2013).

- Mat Snow, "George Harrison Living in the Material World", Mojo, November 2006, p. 124.

- John Metzger, "George Harrison Living in the Material World", The Music Box, vol. 13 (11), November 2006 (retrieved 4 June 2013).

- Kory Grow, "George Harrison's First Six Studio Albums to Get Lavish Reissues", rollingstone.com, 2 September 2014 (retrieved 4 October 2014).

- Joe Marchese, "Give Me Love: George Harrison’s 'Apple Years' Are Collected On New Box Set", The Second Disc, 2 September 2014 (retrieved 4 October 2014).

- Bruce Eder, "George Harrison Living in the Material World (Bonus Tracks/DVD)", AllMusic (retrieved 4 October 2014).

- Shawn Perry, "George Harrison, Living In The Material World – CD Review", vintagerock.com, October 2006 (retrieved 29 November 2014).

- Allison, p. 116.

- Inglis, p. 44.

- Inglis, pp. 43, 141.

- Inglis, pp. 26–27, 33–34, 82, 141.

Sources

- Dale C. Allison Jr., The Love There That's Sleeping: The Art and Spirituality of George Harrison, Continuum (New York, NY, 2006; ISBN 978-0-8264-1917-0).

- Keith Badman, The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970–2001, Omnibus Press (London, 2001; ISBN 0-7119-8307-0).

- Harry Castleman & Walter J. Podrazik, All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975, Ballantine Books (New York, NY, 1976; ISBN 0-345-25680-8).

- Alan Clayson, George Harrison, Sanctuary (London, 2003; ISBN 1-86074-489-3).

- Peter Doggett, You Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the Breakup, It Books (New York, NY, 2011; ISBN 978-0-06-177418-8).

- George Harrison, I Me Mine, Chronicle Books (San Francisco, CA, 2002; ISBN 0-8118-3793-9).

- Clinton Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades (20th Anniversary Edition), Faber and Faber (London, 2011; ISBN 978-0-571-27240-2).

- Elliot J. Huntley, Mystical One: George Harrison – After the Break-up of the Beatles, Guernica Editions (Toronto, ON, 2006; ISBN 1-55071-197-0).

- Ian Inglis, The Words and Music of George Harrison, Praeger (Santa Barbara, CA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-313-37532-3).

- Peter Lavezzoli, The Dawn of Indian Music in the West, Continuum (New York, NY, 2006; ISBN 0-8264-2819-3).

- Simon Leng, While My Guitar Gently Weeps: The Music of George Harrison, Hal Leonard (Milwaukee, WI, 2006; ISBN 1-4234-0609-5).

- Chip Madinger & Mark Easter, Eight Arms to Hold You: The Solo Beatles Compendium, 44.1 Productions (Chesterfield, MO, 2000; ISBN 0-615-11724-4).

- Chris O'Dell with Katherine Ketcham, Miss O'Dell: My Hard Days and Long Nights with The Beatles, The Stones, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, and the Women They Loved, Touchstone (New York, NY, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4).

- Robert Rodriguez, Fab Four FAQ 2.0: The Beatles' Solo Years, 1970–1980, Backbeat Books (Milwaukee, WI, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4).

- Nicholas Schaffner, The Beatles Forever, McGraw-Hill (New York, NY, 1978; ISBN 0-07-055087-5).

- Howard Sounes, Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan, Doubleday (London, 2001; ISBN 0-385-60125-5).

- Bruce Spizer, The Beatles Solo on Apple Records, 498 Productions (New Orleans, LA, 2005; ISBN 0-9662649-5-9).

- Bill Wyman, Rolling with the Stones, Dorling Kindersley (London, 2002; ISBN 0-7513-4646-2).