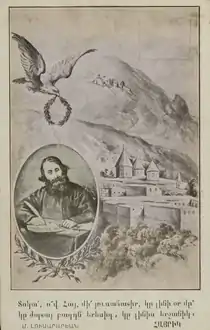

Mkrtich Khrimian

Mkrtich Khrimian[lower-alpha 1] (classical Armenian: Մկրտիչ Խրիմեան, reformed: Մկրտիչ Խրիմյան; 4 April 1820 – 29 October 1907) was an Armenian Apostolic Church leader, educator, and publisher who served as Catholicos of All Armenians from 1893 to 1907. During this period he was known as Mkrtich I of Van (Մկրտիչ Ա Վանեցի, Mkrtich A Vanetsi).

Catholicos Mkrtich I of Van | |

|---|---|

| Catholicos of All Armenians | |

.png.webp) A 1900 portrait of Khrimian by Yeghishe Tadevosyan | |

| Church | Armenian Apostolic Church |

| See | Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin |

| Elected | 5 May 1892 |

| Installed | 26 September 1893 |

| Term ended | 29 October 1907 |

| Predecessor | Magar I |

| Successor | Matthew II Izmirlian |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Mkrtich Khrimian |

| Born | 4 April 1820 Van, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 29 October 1907 (aged 87) Etchmiadzin, Erivan Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Buried | Etchmiadzin Cathedral |

| Nationality | Armenian Ottoman subject (until 1893)[1] Russian subject (from 1893)[2] |

| Occupation | Priest, educator, publisher, traveler, thinker, journalist, activist[3] |

| Previous post | Prelate of Van (1879–85) Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople (1869–73) Prelate of Taron and Abbot of Surb Karapet Monastery (1862–68) Abbot of Varagavank (1857–62) |

A native of Van, one of the largest cities in Turkish (Western) Armenia, Khrimian became a celibate priest (vardapet) in 1854 after the death of his wife and daughter. In the 1850s and 1860s he served as the abbot of two important monasteries in Turkish Armenia: Varagavank near Van and Surb Karapet Monastery near Mush. During this period he established schools and journals in both monasteries. He served as Patriarch of Constantinople—the most influential figure within the Ottoman Armenian community—from 1869 to 1873 and resigned due to pressure from the Ottoman government which saw him as a threat. He was the head of the Armenian delegation at the 1878 Congress of Berlin. Returning from Europe, he encouraged Armenian peasants to follow the example of Christian Balkan peoples by launching an armed struggle for autonomy or independence from the Ottoman Turks.

Between 1879 and 1885 he served as prelate of Van, after which he was forced into exile to Jerusalem. He was elected as head of the Armenian Church in 1892, however, he was enthroned more than a year later and served in that position until his death. He opposed the Russian government's attempt to confiscate the properties of the Armenian Church in 1903, which was later canceled partly due to his efforts. Khrimian further endorsed the liberation movement of the Armenian revolutionaries.

He is a towering figure in modern Armenian history and has been affectionately called Khrimian Hayrik[lower-alpha 2] (hayrik is diminutive for "father").[6] A well-known defender of Armenian interests and aspirations, his progressive activities are seen as having laid the groundwork for the rise of Armenian nationalism and the consequent national liberation movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Early life, education, and travels

Khrimian was born in the Aygestan (Aikesdan) quarter of Van.[7] His father, a weaver, died when Mkrtich was a child[8][9] and he was brought up by his uncle, Khachatur, a merchant.[7] The root of his last name, Khrim, is the Armenian language term for Crimea, suggests a link his family had with the peninsula.[10] He received informal education at parochial schools of Lim and Ktuts islands in Lake Van and Varagavank, where he studied classical Armenian, history, and ecclesiastical literature.[11][8] Upon returning to Van in 1842, he embarked on a journey across the region and made a pilgrimage to Etchmiadzin, the center of the Armenian Church. Khrimian wished to continue his education at a European university, but this desire was never realized. He lived in Constantinople from 1844 to 1846 where he made connections with Armenian intellectuals.[7]

Returning to Van in 1846, he married Mariam Sevikian. In 1847 he crossed to Persia and the Russian Caucasus, where he visited the Ararat plain, Shirak, and Nakhichevan. He lived in Alexandropol (Gyumri) for six months.[7] In 1848 once again moved to Constantinople via Tiflis, Batumi, and Trabzon. From 1848 to 1850 he taught at an all-girl school in Constantinople's Khasgiugh (Hasköy) quarter.[12][13] In 1851 he traveled to Cilicia where he was sent to report on the state of Armenian schools.[14] By traveling and living in various Armenian-populated provinces, he acquired an intimate knowledge of the problems and aspirations of ordinary Armenians.[15] He was upset with the apathy the upper and middle classes of the Armenian community of Constantinople showed towards provincial Armenians.[8]

Returning to Van in 1853, he found himself with no immediate family left; his wife, daughter, and mother had died. He thereafter decided to devote himself to a life in the Armenian Apostolic Church.[11] In 1854, at age 34, Khirimian was ordained as vardapet (celibate priest) at the Aghtamar Cathedral in Lake Van.[14] In 1855 he was appointed abbot of the Holy Cross Church in Scutari (Üsküdar), near Constantinople. Khrimian began production of the periodical Artsvi Vaspurakan at a publishing house located next to his Scutari church.[16]

Van, Mush, and Constantinople

Monasteries of Varag and Surb Karapet

Khrimian returned to Van in 1857 and established the Zharangavorats School at Varagavank monastery. He founded a publishing house at the monastery, through which he resumed the publication of Artsvi Vaspurakan in 1859. Its publication continued until 1864.[17][8]

In 1862 he was appointed abbot of the Surb Karapet Monastery near Mush, which meant he was also the prelate of Taron. He revitalized the monastery and transformed it into a flourishing center.[8] He founded a school there and a journal, called Artsvik Tarono.[18] He succeeded in convincing the wali (governor) of the Erzurum Vilayet to lower taxes for Armenians.[8]

Patriarch of Constantinople

On 20 October 1868, Khrimian was ordained as a bishop in Etchmiadzin. On 4 September 1869 he was elected as the Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople, who was the de facto leader of the Armenian community of the Ottoman Empire in both religious and secular matters.[19][20] According to Ali Tekkoyun, a Turkish scholar of religion, his election indicated that the Amira (wealthiest) class and the imperial authorities lost power over the Armenians as went against their interests.[21] He cleared the patriarchate's debt and sought to increase the provincial representation in the Armenian National Assembly. As the de facto political leader of the Christian Armenian millet in the eyes of the Sublime Porte,[22] he prepared a detailed report documenting instances of oppression, persecution, and miscarriage of justice in the Armenian provinces and presented the document to the Sublime Porte.[8] Khrimian used the position to advance the interests and conditions of the poor and oppressed provincial Armenians.[15]

The Khrimian report, officially titled First Report on Provincial Oppressions needs to be understood in the context of the Tanzimat reforms (1839, 1856).[23] Aimed at centralizing the administration and improving the tax base of the government, the reforms had not been effectively implemented in the more peripheral parts of the Empire, among them the Anatolian provinces. As a consequence, the local populations often suffered from double taxation, both from the central government and from the part of local tribal leaders who had access to tax farming rights, most of them Kurdish notables.[24] Issues explicitly mentioned in Khrimian's report include: violence committed by tax farmers against the local population, forced conversions to Islam and other crimes committed out of religious fanaticism, over-taxation, and neglect of tax farmer duties, leading to harvest losses. The report also made several suggestions on how to address the above-mentioned problems: In particular, the Kurdish tribesmen were supposed to be disarmed and taught an agricultural lifestyle. Moreover, the report asked for the creation of an effective police force, with Armenians being allowed to serve at all levels, and for transparent communication of the Sublime Porte's orders.[25][26]

His outspokenness about the issues facing the Armenian population annoyed not only the Ottoman authorities but some of the Armenian wealthy elite as well.[8] According to Gerard Libaridian, the promotion of rights of provincial Armenians "made him an enemy of many influential Armenians in Istanbul."[27] He was compelled to resign by the Ottoman government in 1873.[28] Armayis Vartooguian wrote in 1896 that Khrimian "could have held the post of Patriarch of Constantinople for life had he not been driven to resign by the intrigues of the Turkish Government, which disliked him very much because of his zeal for the well-being of his flock."[29]

Following his resignation, Khrimian dedicated his time to literary pursuits.[8]

Berlin Congress

In the aftermath of the 1877–78 Russo-Turkish War, Khrimian led the Armenian delegation at the Congress of Berlin.[30] The delegation's mission was to present a memorandum to the great powers concerning the implementation of reforms in the Armenian provinces of the Ottoman Empire.[8] The delegation's main goal was to secure substantial reforms in the Armenian provinces that would be supervised by European powers—which meant Russia in reality, as its troops where stationed in parts of Armenia. Armenians hoped that Russian pressure (and threat of intervention) would force the Ottoman government to improve conditions in the Armenian provinces. The Armenian delegation furthermore demanded some form of autonomy for the Armenian provinces, similar to the Maronite autonomy in Mount Lebanon, but did not advocate breakup of the Ottoman Empire or annexation of the Armenian provinces into Russia.[31]

The Treaty of Berlin, which was signed on 13 July 1878, is considered a failure of the Armenian mission to the congress by historians. It failed to force the Ottoman government to implement real reforms.[30] Panossian writes that all the Armenian delegation received were "toothless promises."[31] In the congress, Khrimian witnessed the Christian Balkan peoples (Serbs, Montenegrins, and Bulgarians) achieving independence or some degree of autonomy.[22]

After returning to Constantinople, Khrimian delivered a series of speeches "which secured him a place in the radicalisation of Armenian thinking, and the clear and forceful articulation of demands based on nationalist principles."[33] He gave a well-known[34] sermon in which he called for the armament of the Armenians in order to fight for an independent Armenia.[22] He told his flock that "Armenia, in contrast with the Christian states of the Balkans, did not win autonomy from the Porte because no Armenian blood had been shed in the cause of freedom."[30] Famous for its allegories, the sermon is considered to have initiated the Armenian revolutionary movement.[8]

In the sermon, he "used an analogy of a ladle and dish with the sword and freedom in explaining the Balkan countries' struggle for freedom during the Congress. For him, the freedom of Armenia was only possible through the use of armed force."[35] In particular, he stated: "There, where guns talk and swords make noise, what significance do appeals and petitions have?"[36] He added:

People of Armenia, of course you understand well what the gun could have done and can do. And so, dear and blessed Armenians, when you return to the Fatherland, to your relatives and friends, take weapons, take weapons and again weapons. People, above all, place the hope of your liberation on yourself. Use your brain and your fist! Man must work for himself in order to be saved.[37]

Prelate of Van and exile

After his return from Europe, Khrimian was appointed Prelate of Van in 1879.[38][13] He opened new schools, including the first agricultural school in Armenian lands.[8][38] In the 1880s he supported the Armenian secret societies devoted to the cause of national liberation, such as Sev khach ("Սև խաչ", Black cross) of Van and Pashtpan hayrenyats ("Պաշտպան հայրենյաց", Defender of the Fatherland).[38][13] The Ottoman government, which looked unfavorably on his activities, suspended him in 1885 and sent him to Constantinople,[38] where he could be controlled by the authorities.[39]

Following the 15 July 1890 Kum Kapu demonstration, four representatives of the Armenian National Assembly (Khrimian, Garegin Srvandztiants, Matthew Izmirlian, Grigoris Aleatjian) presented a report criticizing the Ottoman government for the treatment of the Armenian peasantry.[39] In December 1890,[39] he was exiled to Jerusalem "under pretense of being on a pilgrimage."[8] He lived in the St. James monastery in the city's Armenian Quarter.[39]

Catholicos

On 5 May 1892, an election held at Etchmiadzin unanimously elected Khrimian to the position of Catholicos of the Armenian Apostolic Church.[40][41][42][43] According to Vartooguian, "Khrimian's popularity was so overwhelming that any one opposing him would be recognized by the nation as a traitor. Khrimian was recognized as the standard of patriotism, and whoever sought the best interests of the nation could not but favor his election."[44] Vartooguian adds that the Russian imperial government was displeased with his election as they sought to incorporate the Armenian Church under the jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Church in an attempt to Russify the Armenian population.[45]

_(14750077966).jpg.webp)

Khrimian, aged 72, was not initially allowed to travel to Etchmiadzin by Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II. Over a year later, after the Russian emperor's request was he granted permission to travel, but only if he did not set foot in Turkey.[1] According to Hacikyan et al., the Ottomans feared "excessive manifestations of jubilations by the Armenians."[8] The Ottoman government forbade Khrimian from traveling to Echmiadzin through their territory, and so he was required to travel via Jaffa, Alexandria, Trieste, Vienna, Odessa, Sevastopol, Batumi, and then Tiflis.[28] Some 17 months after his election, he was enthroned as Catholicos on 26 September 1893.[43][46] His Ottoman citizenship was revoked and he became a Russian subject.[1][2]

In 1895, he traveled to Saint Petersburg to meet the Russian Tsar Nicholas II to request the implementation of reforms in the Ottoman Empire's Armenian provinces. During the Hamidian massacres of 1894–96, Khrimian provided material assistance to the Armenian refugees.[38][13] Among his other accomplishments were the renovations of numerous ancient monasteries and churches.[8]

In June 1903, the Russian government issued an edict to close down Armenian schools and confiscate the properties of the Armenian Church,[47] including the treasures of Etchmiadzin.[48] The act had the primary purpose of accelerating the process of Russification of the Armenian people and church.[49] Khrimian collaborated with the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF or Dashnaktsutyun) to organize mass demonstrations against the edict.[50] According to the historian Rouben Paul Adalian, it was a combination of Dashnaktsutyun's popular resistance and Khrimian's personal defiance that resulted in the edict being canceled in 1905.[51]

In 1907, Khrimian clarified the relations between the patriarch of Constantinople and emphasized the primacy of the see of Echmiadzin.[28] In September of that year he sent a letter to Nicholas II in which he called upon the Russian government to prevent the violence then facing the Ottoman Empire's Armenian population.[52]

Views and ideological influence

Progressivism

In the 1860s and 1870s, Khrimian was, along with Harutiun Svadjian, one of the major liberal Armenian activists in the Ottoman Empire. At the same time, liberals like Grigor Artsruni, Mikael Nalbandian, and Stepanos Nazarian were active in the Russian Empire.[54] Arra Avakian described him as a "very progressive educator."[55] American feminist Alice Stone Blackwell wrote in 1917: "All his views were progressive" and praised his promotion of female education: "He was a strong advocate of education for girls, and in one of his books, The Family of Paradise, he argues against the prevailing Oriental idea that husbands have a right to rule over their wives by force."[56] Derderian also noted his "belief in the importance of educating women" and his encouragement of "participation of women in spreading enlightenment principles."[11] Another author stated that he made "voluminous contribution to progressive Armenian intellectualism."[57] Vartooguian, writing in 1896, suggested that Khrimian "was a conservative in matters of the Church."[58]

Nationalism

Razmik Panossian writes that Khrimian had a powerful influence on Armenian nationalism.[59] According to Panossian, he is the "single most important nineteenth century figure to have entered Armenian consciousness as the bearer of the radical message of national liberation".[10] According to Tekkoyun, "Khrimian was a prominent figure in the formation of the Armenian nationalism."[60] H. F. B. Lynch, who visited Etchmiadzin in 1893, wrote about Khrimian in his book on Armenia: "With him religion and patriotism are almost interchangeable terms."[61] In the words of Adalian, Khrimian is "revered for his patriotic fervor and staunch defense of Armenian national interests."[62] Another author described him as a "major spokesman for Armenian nationalist aspirations on the international stage."[63] According to Tekkoyun, Khrimian "always advocated the awareness of laymen with nationalistic and patriotic ideas, which was possible only through the medium of journals and literature."[64] Khrimian particularly emphasized the use of vernacular language in his writings.[3]

Khrimian's view of Armenian nationalism as a cultural reawakening transformed into nationalism as an armed revolutionary movement in response to the repressive regime of Ottoman and Russian government as well as European policies towards Armenia.[65] Khrimian explicitly endorsed the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutyun) in an 1896 letter to the Armenians of Van, in which he wrote:[66]

The appearance of political parties among you is an example of the rebirth of the historical houses of our nobility, while the Dashnaktsutyun Party is the new Armenian knighthood. Its pioneers have shown themselves to be true knights in Vaspurakan [i.e. the region around Van] and elsewhere. Rise, rise, Armenians, join this new Armenian knighthood, take heart ...

Before this the church had maintained a distance from the Armenian revolutionary groups as the latter saw the former as a conservative institution. It was Khrimian who welcomed revolutionary activism, especially by the Dashnaktsutyun, the most influential Armenian party.[67] According to Panossian, Khrimian thus radicalised, to a certain degree, the Armenian Church and as such secularised in its vision of the Armenian nation.[66]

Death and legacy

Khrimian died on 29 October 1907. He was buried, like many of his predecessors, at the courtyard of Etchmiadzin Cathedral. Sculptor Sergey Merkurov made his death mask.[68]

Khrimian was revered by Armenians during his lifetime.[58] He was called Hayrik (diminutive for "father") since his time as abbot of Surb Karapet Monastery near Mush in the early 1860s.[69][lower-alpha 3] Sarkis Atamian claims that "[n]o man, perhaps, in Armenian history, has come to symbolize the kind, wise, paternalistic leader of his flock as did Khrimian who was given the title Hairig (little father) in affection by his people."[71] Jack Kalpakian describes Khrimian as "second only to the mythical Haik as the nation's father figure."[72] Khrimian largely focused his efforts on the common people rather than the Armenian elite and is thus considered a "hero of the common people."[73][74] Catholicos Vazgen I (r. 1955–94) called Khrimian the "greatest revolutionary [of the Armenian peasantry]".[lower-alpha 4]

Panossian writes that Khrimian was committed throughout his life to the betterment of the conditions of provincial Armenian and of Armenian rights in general. [75] Khrimian has been described as "one of the few truly great figures in the history of the Armenian Church" and "one of the most famous and beloved national-religious figures of his time."[8] Another author called him "the most beloved Armenian patriarch of modern times."[76] Patricia Cholakian wrote of him: "a man of great personal holiness, had been among the first to inspire the persecuted Armenians to a love of learning and a sense of pride in their heritage."[77] The prominent linguist Hrachia Acharian called him a true Christian, a true patriot, and a true popular man.[78]

The Missionary Herald wrote in 1891 about Khrimian: "a man to whom all the Armenian nation look up to with great respect. He has labored honestly and earnestly for good of his nation."[79] Alice Stone Blackwell wrote of him in 1917 as "the grandest figure in modern Armenian history" and added that "He was deeply loved and venerated for his wisdom and saintliness."[56] Prominent Armenian poet Avetik Isahakyan wrote in a 1945 article: "The Armenian people will not forget him. The more time passes, the brighter his memory will become. He will look at the Armenian people from the depth of centuries and speak with a familiar language about her cherished aspirations and immortal goals."[80]

Khrimian is the subject of paintings of several prominent Armenian artists, such as Ivan Aivazovsky, Yeghishe Tadevosyan, and Vardges Sureniants. Armenian-American composer Alan Hovhaness wrote a concerto titled Khrimian Hairig in October 1944. In his own words, "The music was inspired by a portrait of the heroic priest Khrimian Hairig, who led the Armenian people through many persecutions." The composition was first commercially recorded in 1995 by the Manhattan Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Richard Auldon Clark.[81] A school in Yerevan, Armenia's capital, founded by Khrimian in 1906 and renamed for the 26 Baku Commissars during the Soviet period, was renamed after him in 1989.[82]

Publications

Khrimian authored essays and books. His most notable works are the following:[8]

- 1850: Հրաւիրակ Արարատեան, Hravirak Araratian (Convoker to Ararat): "a verse essay in classical Armenian in which he assumes the role of guide and leads a group of youths though the history and geography of the ancestral homeland, extolling its ancient glories and exquisite beauty in an attempt to instill a love and passion for the mother country in the young generation"[8]

- 1851: Հրաւիրակ երկրին աւետեաց, Hravirak yerkrin avetiatz (Convoker to the Promised Land): "a similar verse essay published after a trip to the Holy Land in which he leads youths on a tour of the holy sites, teaching them the essence of Christianity as they go."[8]

- 1876: Խաչի ճառը, Khachi char (Discourse on the Cross)

- 1876: Ժամանակ եւ խորհուրդ իւր, Zhamanak yev khorhurd yur (Time and its mystery)

- 1876: Դրախտի ընտանիք, Drakhti entanik (The family of paradise)

- 1878: Սիրաք եւ Սամուէլ, Sirak yev Samuel: "a treatise on child education"

- 1894: Պապիկ եւ թոռնիկ, Papik yev tornik (Grandfather and grandson): Agop Jack Hacikyan et al. consider it his best work.[8]

- 1900: Թագաւորաց ժողով, Tagavorats zhoghov (The meeting of kings)

- 1901: Վերջալոյսի ձայներ, Verjaluysi dzayner (Sounds of twilight): a collection of poetry

Notes

- Also transliterated as Mkrtič, Mgrdich, Mugerditch, Mgerdich and Xrimean, Xrimian, Xrimyan, Khrimyan. Turkish: Mıgırdıç Hrimyan[4] or Mıgırdıç Kırımyan[5]

- Also transliterated as Hairik, Hayrig, Hairig; classical: Խրիմեան Հայրիկ; reformed: Խրիմյան Հայրիկ

- Khrimian apparently embraced the suffix. Hovhannes Tumanyan wrote that in 1896, in the aftermath of the Hamidian massacres, a man who lost his entire family in the massacres came to Khrimian in Etchmiadzin to tell his story. Khrimian, in response, told the man: "You've lost 20 sons, I've lost 20 thousand and 20."; thus referring to tens of thousands of Armenians who were killed in the massacres as his "sons."[70]

- Հայ գաւառացի ժողովուրդը պէտք ունէր առաքեալի մը շունչին ու խօսքին, յեղափոխականի մը շարժումին ու կենդանի գործին: Սխալած պիտի չըլլանք եթէ ըսենք թէ այդ մեծագոյն յեղափոխականը մեր մէջ Խրիմեան Հայրիկը կը հանդիսանայ, թէ° իր կենդանի խօսքով, թէ° իր գործով:[42]

References

- Kostandyan 2006, pp. 84–85.

- Vartooguian 1896, p. 91.

- Tekkoyun 2011, p. 53.

- Selçuk Akşin Somel. "Osmanlı Ermenilerinde Kültür Modernleşmesi, Cemaat Okulları ve Abdülhamid Rejimi" (PDF) (in Turkish). Sabancı University. p. 4.

Söz konusu taşra tepkisinin entellektüel temsilciliğini Van'lı rahip, gazeteci ve öğretmen Mıgırdıç Hrimyan (1820–1907) yaptı.

Çelik, Yüksel. "Dış Müdahale, İsyanlar ve Komitacılık Ekseninde Ermeni Meselesi ya da Anadolu Islahatı" (in Turkish). Marmara University.Bu ön hazırlıklardan sonra Mıgırdıç Hrimyan Efendi başkanlığında katıldıkları Berlin Kongresi'ne ...

- Hasan Celal Güzel (2001). Osmanlı'dan günümüze Ermeni sorunu (in Turkish). Yeni Türkiye Yayınları. p. 403.

... Gregoryen milletinin adeta parlamentosuna dönüşecek ve 1869' da seçilen Patrik Mıgırdiç Kırımyan'ın önderliğinde sözgelimi Ermeni vilayetleri ...

Kurdakul, Necdet (1976). Osmanlı İmparatorluğundan Orta Doğu'ya: Belgelerle Şark meselesi (in Turkish). Dergâh Yayınları.... İngiliz konsolosunun teklifiyle kendisini Ermenilerin lideri sayan Mıgırdıç Kırımyan Efendi ...

- Sheklian, Christopher (2014). "Venerating the Saints, Remembering the City: Armenian Memorial Practices and Community Formation in Contemporary Istanbul". In Agadjanian, Alexander (ed.). Armenian Christianity Today: Identity Politics and Popular Practice. Ashgate Publishing. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-4724-1271-3.

- Voskanian 2007, p. 98.

- Hacikyan, Agop Jack; Basmajian, Gabriel; Franchuk, Edward S.; Ouzounian, Nourhan (2005). "Mkrtich Khrimian (Hayrik)". The Heritage of Armenian Literature: From the eighteenth century to modern times. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. pp. 236–238. ISBN 978-0-8143-3221-4.

- Tekkoyun 2011, p. 51.

- Panossian 2006, p. 167.

- Derderian, Dzovinar (16 December 2014). "Mapping the Fatherland: Artzvi Vaspurakan's Reforms through the Memory of the Past". houshamadyan.org.

- Voskanian 2007, p. 99.

- Kostandyan, E. (1981). "Մկտրիչ Ա Վանեցի [Mkrtich I of Van]". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia Volume 7 (in Armenian). pp. 641–642.

- Voskanian 2007, p. 101.

- Panossian 2006, p. 168.

- Voskanian 2007, p. 102.

- Voskanian 2007, p. 103.

- Voskanian 2007, pp. 103–104.

- Voskanian 2007, p. 104.

- Panossian 2006, p. 70.

- Tekkoyun 2011, p. 89.

- Tekkoyun 2011, p. 52.

- Miller 2011, p. 29.

- Özbek 2012, p. 792.

- Kheremian 1872.

- Suny 2015, p. 61.

- Panossian 2006, p. 174.

- Walker 1990, pp. 428–429.

- Vartooguian 1896, p. 80.

- Zeidner, Robert F. (1976). "Britain and the Launching of the Armenian Question". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 7 (4): 473. doi:10.1017/S002074380002465X. JSTOR 162505.

- Panossian 2006, p. 170.

- Government of Armenia (2002). "Հայաստանի Հանրապետության Արմավիրի Մարզի Պատմության և Մշակույթի Անշարժ Հուշարձանների Պետական Ցուցակը [List of the Immovable Historical And Cultural Monuments in the Armavir Province of the Republic of Armenia]" (in Armenian). Armenian Legal Information System. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014.

- Panossian 2006, pp. 168–169.

- Arnavoudian, Eddie (30 December 2002). "In defence of the Armenian National Liberation Movement". groong.usc.edu. University of Southern California. Armenian News Network / Groong.

- Tekkoyun 2011, p. 56.

- Tekkoyun 2011, p. 96.

- Tekkoyun 2011, p. 97.

- "Խրիմյան Հայրիկ [Khrimyan Hayrik]" (in Armenian). Yerevan State University Institute for Armenian Studies. Archived from the original on 2017-10-26.

- Kostandyan 2006, p. 83.

- Kostandyan 2006, p. 84.

- Voskanian 2007, p. 105.

- "190ամեակ Խրիմեան Հայրիկի [Khrimyan Hayrik's 190th anniversary]" (PDF). getronagan.k12.tr (in Armenian). Istanbul: Getronagan Armenian High School. 2010.

- Ormanian 1912, p. 238.

- Vartooguian 1896, p. 86.

- Vartooguian 1896, p. 90.

- Kostandyan 2006, p. 85.

- Barrett, David B.; Kurian, George Thomas; Johnson, Todd M. (2001). World Christian encyclopedia: a comparative survey of churches and religions in the modern world, Volume 1 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-19-510318-2.

- Hewsen 2001, p. 259.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 40.

- Hovannisian 1971, p. 41.

- Adalian 2010, p. 130.

- Nersissian, M. G. (1993). "Խրիմյան Հայրիկի դիմումը Նիկոլայ Երկրորդին (1907 թ.) և արխիվային այլ նյութեր Հայկական հարցի ու հայ կամավորական շարժման մասին (1912—1915 թթ.) [Catholicos M. Khrimian's Appeal to Nicolas II (1907) and Other Archive Materials on the Armenian Question and about the Armenian Volunteer Movement (1912–1915)]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian) (1–2): 165–180. ISSN 0135-0536.

- Manjyan, H. (July 2012). "Մի նկարի պատմություն. Խրիմյան Հայրիկ". Hay Zinvor (in Armenian). Defense Ministry of Armenia.

- Barkhudaryan, Vladimir, ed. (2012). Հայոց Պատմություն Նոր շրջան դասագիրք հանրակրթական դպրոցի 8-րդ դասարանի համար [Armenian History New Era 8th grade textbook for public schools] (PDF) (in Armenian). Yerevan: Manmar. p. 71. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04.

- Avakian, Arra S. (1998). "Van". Armenia: A Journey Through History. Electric Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-916919-24-5.

- Blackwell, Alice Stone (1917). "Murmurs of a Patriot". Armenian Poems. Boston: Atlantic Printing Company. p. 201.

- "Iron Ladle by Khrimyan Hayrig". The Armenite. William Bairamian (commentary). 4 March 2014.

Hayrig's voluminous contribution to progressive Armenian intellectualism cannot be adequately discussed here.

CS1 maint: others (link) - Vartooguian 1896, p. 79.

- Panossian 2006, p. 141.

- Tekkoyun 2011, p. 58.

- Lynch 1901, pp. 236–237.

- Adalian 2010, pp. 446–447.

- Ramet 1989, p. 456.

- Tekkoyun 2011, p. 54.

- Payaslian 2007, p. 119.

- Panossian 2006, p. 198.

- Payaslian 2007, pp. 121–122.

- Harutyunyan, V. (1983). "Մերկուրով Սերգեյ [Merkurov Sergey]". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia Volume 9 (in Armenian). Yerevan. p. 494.

Մ-ի հանած առաջին դիմակը Խրիմյան Հայրիկինն էր (1907)

- Onanyan, Vardan (15 December 2010). "Արծվաթեւ մարտնչողը". The Armenian Times (in Armenian).

- Tumanyan, Hovhannes (1985). "Երկու հայր". Ընտիր երկեր, 2 հատորով [Selected works, in 2 volumes] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Sovetakan grogh.

- Atamian, Sarkis (1955). The Armenian Community: The Historical Development of a Social and Ideological Conflict. New York: Philosophical Library. p. 84.

- Kalpakian, Jack V. (2006). "Khrimian, Mkrtich (1820–1907)". In Domenico, Roy P.; Hanley, Mark Y. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Modern Christian Politics. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-32362-1.

- Tekkoyun 2011, p. 50.

- Libaridian, Gerard J. (2011). "What Was Revolutionary about Armenian Revolutionary Parties in the Ottoman Empire?". In Suny, Ronald G.; Göçek, Fatma Müge; Naimark, Norman M. (eds.). A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-19-978104-1.

- Panossian 2006, pp. 167–168.

- Raffi (2000). The Fool: Events from the Last Russo-Turkish War (1877–78). Donald Abcarian (translator). Princeton, NJ: Gomidas Institute. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-9535191-8-7.

- Cholakian, Patricia (2006). "Flight from Van: Memories of an Armenian Genocide Survivor". In Bronner, Stephen Eric; Thompson, Michael (eds.). The Logos Reader: Rational Radicalism and the Future of Politics. University Press of Kentucky. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-8131-9148-5.

- Acharian, Hrachia (1944). "Մկրտիչ կաթողիկոս Խրիմյան [Catholicos Mkrtich Khrimian]". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin. 1 (4–5): 15–19.

- "____". The Missionary Herald. Boston. 87. 1891.

- Isahakyan, Avetik (1945). "Խրիմյան Հայրիկը (Հուշեր) [Khrimian Hayrik (Memories)]". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin (5): 38–42.

- Fujihara Hovhaness, Hinako. "Alan Hovhaness (1911–2000): Khrimian Hairig • Guitar Concerto • Symphony No. 60 "To the Appalachian Mountains"". Naxos Records.

- "The schools subordinated to the municipality of Yerevan". yerevan.am. Yerevan Municipality.

Bibliography

- Adalian, Rouben Paul (2010). Historical Dictionary of Armenia. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7450-3.

- Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). "The Monastery of Ējmiatsin". Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-33228-4.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1971). "Russian Armenia. A Century of Tsarist Rule". Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas. Franz Steiner Verlag. 19 (1): 31–48. JSTOR 41044266.

- Kheremian, Meguerditch (11 April 1872). "First Report on Provincial Oppressions, submitted to the Sublime Porte in the Name of the Armenian National Assembly". Constantinople.

- Kostandyan, Emma (2006). "Մկրտիչ Խրիմյանն ու հայկական Երուսաղեմը [Mkrtich Khrimyan and the Armenian Jerusalem]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian) (2): 79–87. ISSN 0135-0536.

- Lynch, H. F. B. (1901). Armenia, travels and studies. Volume I: The Russian Provinces. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. pp. 236–7.

- Miller, Meaghan (2011). The Disintegration of Ottoman-Armenian Relations in the Tanzimat and Hamidian Periods, 1839-1896 (Thesis). University of Colorado, Boulder.

- Ormanian, Malachia (1912). The Church of Armenia. G. Marcar Gregory (translator), J. E. C. Welldon. Oxford: Mowbray.

- Özbek, Nadir (2012). "The Politics of Taxation and the Armenian Question during the Late Ottoman Empire, 1876-1908". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 54 (2): 770–797. doi:10.1017/S0010417512000412.

- Panossian, Razmik (2006). The Armenians: From Kings and Priests to Merchants and Commissars. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13926-7.

- Payaslian, Simon (2007). The History of Armenia. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-7467-9.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (1989). Religion and Nationalism in Soviet and East European Politics. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-0854-6.

- Suny, Ronald G. (2015). "They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else": A History of the Armenian Genocide. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14730-7.

- Tekkoyun, Ali (2011). "The role of religion in the formation of nationalism, two case studies: Turkish and Armenian nationalisms" (MA thesis). University of Utah.

- Vartooguian, Armayis P. (1896). Armenia's Ordeal (second ed.). New York: Privately published.

- Voskanian, Shoghik (2007). "Մկրտիչ Խրիմյանի կյանքը, մանկավարժական լուսավորական գործունեությունը [The life and pedagogical enlightening activity of Mkrtich Khrimian]". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin. 63 (9): 97–109.

- Walker, Christopher J. (1990). Armenia: The Survival of a Nation (revised second ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-04230-1.

Further reading

- Hayrig: a celebration of his life and vision on the eightieth anniversary of his death (1907–1987). New York: Prelacy of the Armenian Apostolic Church of America. 1987. OCLC 16985479.

- Խրիմյան Հայրիկ. Երկեր (PDF) (in Armenian). Yerevan State University Press. 1992.

- Antaramian, Richard Edward (2014). In Subversive Service of the Sublime State: Armenians and Ottoman State Power, 1844–1896 (dissertation). University of Michigan.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mkrtich Khrimian. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Mkrtich Khrimian (Armenian Wikiquote) |

| Religious titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ignatios I of Constantinople |

Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople 1869–1873 |

Succeeded by Nerses II of Constantinople |

| Preceded by Magar I |

Catholicos of the Mother See of Holy Echmiadzin and All Armenians 1892–1907 |

Succeeded by Matthew II |