Armenian Revolutionary Federation

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Armenian: Հայ Յեղափոխական Դաշնակցութիւն, ՀՅԴ (classical spelling)[lower-alpha 1], abbr. ARF or ARF-D) also known as Dashnaktsutyun[lower-alpha 2] (collectively referred to as Dashnaks for short), is an Armenian nationalist and socialist political party[24][25][26][27] founded in 1890 in Tiflis, Russian Empire (now Tbilisi, Georgia) by Christapor Mikaelian, Stepan Zorian, and Simon Zavarian.[28] Today the party operates in Armenia, Artsakh, Lebanon, Iran and in countries where the Armenian diaspora is present. Although it has long been the most influential political party in the Armenian diaspora, it has a comparatively smaller presence in modern-day Armenia.[29] As of December 2018 was represented in two national parliaments with three seats in the National Assembly of Artsakh and three seats in the Parliament of Lebanon[30][31] as part of the March 8 Alliance. As of December 2020, the ARF has no seats in the National Assembly of Armenia.

Armenian Revolutionary Federation Հայ Յեղափոխական Դաշնակցութիւն | |

|---|---|

| |

| Other name | Dashnaktsutyun |

| Abbreviation | ARF (English) ՀՅԴ (Armenian) |

| Founders | • Christapor Mikaelian • Stepan Zorian • Simon Zavarian |

| Founded | 1890[1] in Tiflis, Russian Empire (now Tbilisi, Georgia) |

| Headquarters | Hanrapetutyun street 30, Yerevan |

| Newspaper | Yerkir (Երկիր, "Country") and Droshak (Դրօշակ, "Banner") |

| Student wing | • ARF Shant Student Association • ARF Armen Karo Student Association |

| Youth wing | Armenian Youth Federation |

| TV Channel | Yerkir Media |

| Membership | 6,800 (c. 2012)[2] |

| Ideology | United Armenia[a][3][4] Armenian nationalism[5][6][7] Social market economy[8][9] Pro-Russian policies[10][11][12][13] Historical ideologies: Democratic socialism[14][15][16] Revolutionary socialism[17] Anti-communism[18][19][20] (until the late 1980s)[11] |

| Political position | Centre-left |

| European affiliation | Party of European Socialists (observer)[21] |

| National affiliation | March 8 Alliance (in Lebanon) |

| International affiliation | Socialist International[22] |

| Colours | Red and gold |

| Slogan | "Ազատություն կամ մահ" Azatut'yun kam mah ("Freedom or Death")[23] |

| Anthem | "Մշակ, բանուոր" Mshag Panvor ("Peasant and Worker") |

| Affiliates | • Armenian Relief Society • Homenetmen • Hamazkayin • ANCA |

| National Assembly of Armenia | 0 / 132 |

| National Assembly of Artsakh | 3 / 33 |

| Parliament of Lebanon | 3 / 128 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| www | |

^ a: United Armenia is an irredentist concept referring to areas within the traditional Armenian homeland. The ARF idea of "United Armenia" incorporates claims to Western Armenia (eastern Turkey), Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh), the landlocked exclave Nakhichevan of Azerbaijan and the Javakheti (Javakhk) region of Georgia. | |

The ARF has traditionally advocated democratic socialism[14][32] and is a full member of the Socialist International since 2003, which it had originally joined in 1907.[22][33] It has the largest membership of the political parties present in the Armenian diaspora, having established affiliates in more than 20 countries.[34] Compared to other diasporan Armenian parties which tend to primarily focus on educational or humanitarian projects, the ARF is the most politically oriented of the organizations and traditionally has been one of the staunchest supporters of Armenian nationalism.[34] The party campaigns for the recognition of the Armenian Genocide and the right to reparations. It also advocates the establishment of United Armenia, partially based on the Treaty of Sèvres of 1920.

The ARF was founded as a merger of various Armenian political groups, mainly from the Russian Empire, with the declared goal of achieving "the political and economic freedom of Turkish Armenia" by means of armed rebellion.[35] In the 1890's, the party sought to unify the various small groups in the Ottoman Empire that were advocating for reform and defending Armenian villages from the massacres and banditry that were widespread in some of the Armenian-populated areas of the empire. ARF members formed fedayi groups that defended Armenian civilians through armed resistance. The party refrained from revolutionary activity in the Russian Empire until the decision of the Russian authorities to confiscate Armenian Church property in 1903.[36] Initially restricting its demands to the establishment of autonomy and democratic rights for Armenians in the two empires, the party adopted an independent and united Armenia as part of its program in 1919.[37]

In 1918, the party was instrumental in the creation of the First Republic of Armenia, which fell to the Soviet communists in 1920.[38] After its leadership was exiled by the communists, the ARF established itself within Armenian diaspora communities, where it helped Armenians preserve their cultural identity.[39] After the fall of the USSR, it reestablished its presence in Armenia. Prior to Serzh Sargsyan's election as president of Armenia and for a short time thereafter, the ARF was a member of the governing coalition, even though it nominated its own candidate in the presidential elections.[40]

ARF then reentered Sargsyan's cabinet in February 2016 in what was defined as a "long-term political cooperation" agreement with the Republican Party by means of which the ARF would share responsibility for all government policies.[41] The ARF then approved of Sargsyan's nomination as Prime Minister, from which he resigned six days later amid large-scale protests in what came to be known as the Velvet Revolution.[42] By the evening of 25 April 2018, ARF-Dashnaktsutyun had withdrawn from the coalition.

Following the Velvet Revolution, the party lost support from the general public in Armenia and is now being polled at 1–2%. The party then lost political representation after 2018 Armenian parliamentary election after receiving only 3.89% of the votes, which is lower than the 5% minimum threshold required for representation in the parliament.

Early history

In the late 19th century, the Russian Empire became the hub of small groups advocating reform in Armenian-populated areas in the Ottoman Empire. In 1890, recognizing the need to unify these groups in order to be more efficient, Christapor Mikaelian, Simon Zavarian and Stepan Zorian created a new political party called the "Federation of Armenian Revolutionaries" (Հայ Յեղափոխականների Դաշնակցութիւն, Hay Heghapokhakanneri Dashnaktsutyun), which would eventually be called the "Armenian Revolutionary Federation" or "Dashnaktsutiun" in 1890.[1]:103, 106

The Social Democrat Hunchakian Party, an existing Armenian socialist and revolutionary party, initially agreed to join the "Federation of Armenian Revolutionaries." However, the Hunchaks soon withdrew due to disputes over ideological and organizational questions, such as the role of socialism in the party's program. Another faction of non-socialists led by Konstantin Khatisian split from the federation early on. Despite this, the party began to organize itself in the Ottoman Empire and convened its First General Congress in 1892, where a program containing socialist principles was adopted.[35] The original aim of the ARF was to gain autonomy for the Armenian-populated areas in the Ottoman Empire by means of armed rebellion. At the First Congress, the party adopted a decentralized modus operandi according to which the chapters in different countries were allowed to plan and implement policies in tune with their local political atmosphere. The party set its goal of a society based on the democratic principles of freedom of assembly, freedom of speech, freedom of religion and agrarian reform.[28][1]

Russian Empire

The ARF gradually acquired significant strength and sympathy among Russian Armenians. Mainly because of the ARF's stance towards the Ottoman Empire, the party enjoyed the support of the central Russian administration, as tsarist and ARF foreign policy had the same alignment until 1903.[43] On 12 June 1903, the tsarist authorities passed an edict to bring all Armenian Church property under imperial control. This was faced by strong ARF opposition, because the ARF perceived the tsarist edict as a threat to the Armenian national existence. As a result, the ARF leadership decided to defend Armenian churches by dispatching militiamen who acted as guards and by holding mass demonstrations.[43][44] In 1904, the party broke with its old policy of non-struggle against the Tsarist authorities, engaging in acts of terrorism against the imperial bureaucracy and establishing separate schools, courts, and prisons in Russian Armenia.[36]

In 1905–06, the Armenian-Tatar massacres broke out during which the ARF became involved in armed activities. Some sources claim that the Russian government incited the massacres in order to reinforce its authority during the revolutionary turmoil of 1905.[45] The first outbreak of violence occurred in Baku, in February 1905.[46] The ARF held the Russian authorities responsible for inaction and instigation of massacres that were part of a larger anti-Armenian policy. On 11 May 1905, Dashnak revolutionary Drastamat Kanayan assassinated Russian governor general Nakashidze, who was considered by the Armenian population as the main instigator of hate and confrontation between the Armenians and the Tatars. Unable to rely on the state for protection, the Armenian bourgeoisie turned to the ARF. Against the criticisms of their rivals to the left (the Hunchaks, Bolsheviks and Specifists), the Dashnak leaders argued that, given employment discrimination against Armenian workers in non-Armenian concerns, the defence provided to the Armenian bourgeoisie was essential to the safekeeping of employment opportunities for Armenian laborers.[47] The Russian Tsar's envoy in the Caucasus, Vorontsov-Dashkov, reported that the ARF bore a major portion of responsibilities for perpetrating the massacres.[48] The ARF, however, argued that it helped to organize the defence of the Armenian population against Muslim attacks. The blows suffered at the hands of the Dashnakist fighting squads proved a catalyst for the consolidation of the Muslim community of the Caucasus.[46] During that period, the ARF regarded armed activity, including terror, as necessary for the achievement of political goals.[49]

In January 1912, 159 ARF members, being lawyers, bankers, merchants and other intellectuals, were tried before the Russian senate for their participation in the party. They were defended by then-lawyer Alexander Kerensky, who challenged much of the evidence used against them as the "original investigators had been encouraged by the local administration to use any available means" to convict the men.[50] Kerensky succeeded in having the evidence reexamined for one of the defendants. He and several other lawyers "made openly contemptuous declarations" about this discrepancy to the Russian press, which was forbidden to attend the trials, and this in turn greatly embarrassed the senators. The Senate eventually opened an inquiry against the chief magistrate who had brought the charges against the Dashnak members and concluded that he was insane. Ninety-four of the accused were acquitted, while the rest were either imprisoned or exiled for varying periods, the most severe being six years.[51]

Persian Empire

The Dashnaktsutiun held a meeting on 26 April 1907, dubbed the Fourth General Congress, at which ARF leaders such as Aram Manukian, Hamo Ohanjanyan and Stepan Stepanian discussed their engagement in the Iranian Constitutional Revolution.[52] They established that the movement was one that had political, ideological and economic components and was thus aimed at establishing law and order, human rights and the interests of all working people. They also felt that it would work for the benefit and interest of Armenian-Iranians. The final vote was 25 votes in favour and one absentia.[52]

From 1907 to 1908, during the time when the Young Turks came to power in the Ottoman Empire, Armenians from the Caucasus, Western Armenia, and Iran started to collaborate with Iranian constitutionalists and revolutionaries.[52] Political parties, notably the Dashnaktsutiun, wanted to influence the direction of the revolution towards greater democracy and to safeguard gains already achieved. The Dashnak contribution to the fight was mostly military, as it sent some of its well-known fedayees to Iran after the guerrilla campaign in the Ottoman Empire ended with the rise of the Young Turks.[52] A notable ARF member already in Iran was Yeprem Khan, who had established a branch of the party in the country. Yeprem Khan was highly instrumental in the Constitutional revolution of Iran. After the Persian national parliament was shelled by the Russian Colonel Vladimir Liakhov, Yeprem Khan rallied with Sattar Khan and other revolutionary leaders in the Constitutional Revolution of Iran against Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar.[53] Relations between Sattar Khan and the ARF oscillated between amity and resentment. Sometimes he was viewed as being ignorant, while at other times he was dubbed a great hero.[53] Nonetheless, the ARF came to collaborate with him and alongside Yeprem Khan posted many victories including the capture of Rasht in February 1909. At the end of June 1909, the fighters arrived in Tehran and after several battles, took over the Majles building and the Sepahsalar Mosque. Yeprem Khan was then appointed chief of Tehran police. This caused tensions between the Dashnaks and Khan.[53]

Abdul Hamid Period (1894–1908)

The ARF became a major political force in Armenian life. It was especially active in the Ottoman Empire, where it organized or participated in many revolutionary activities. In 1894, the ARF took part in the Sasun Resistance, supplying arms to the local population to help the people of Sasun defend themselves against the Hamidian purges.[54] In June 1896, the Armenakan Party organized the Van Rebellion in the province of Van. The Armenakans, assisted by members of the Hunchakian and ARF parties, supplied all able-bodied men of Van with weapons. They rose to defend the civilians from the attack and subsequent massacre.[55]

To raise awareness of the massacres of 1895–96, members of the Dashnaktsutiun led by Papken Siuni, occupied the Ottoman Bank on 26 August 1896.[56] The purpose of the raid was to dictate the ARF's demands of reform in the Armenian populated areas of the Ottoman Empire and to attract European attention to their cause since the Europeans had many assets in the bank. The operation caught European attention but at the cost of more massacres by Sultan Abdul Hamid II.[57]

During this period, many famous intellectuals joined the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, including Harutiun Shahrigian, Avetik Isahakyan, Hakob Zavriev, Levon Shant, Karekin Khajag, Vartkes Serengülian, Abraham Gyulkhandanyan, Vahan Papazian, Siamanto, Nikol Aghbalian and many others.

The Khanasor Expedition was performed by the Armenian militia against the Kurdish Mazrik tribe on 25 July 1897. During the Defense of Van, the Mazrik tribe had ambushed a squad of Armenian defenders and massacred them. The Khanasor Expedition was the ARF's retaliation.[54][58] Some Armenians consider this their first victory over the Ottoman Empire and celebrate each year in its remembrance.[59][60]

On 30 March 1904, the ARF played a major role in the Second Sasun Uprising. The ARF sent arms and fedayi to defend the region for the second time.[54] Among the 500 fedayees participating in the resistance were famed figures such as Kevork Chavush, Sepasdatsi Murad and Hrayr Djoghk. Although they managed to hold off the Ottoman army for several months, despite their lack of fighters and firepower, Ottoman forces captured Sasun and massacred thousands of Armenians.[54]

In 1905, members of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation organized the failed Yıldız Attempt, an assassination plot on Sultan Abdul Hamid II in the capital of the Ottoman Empire, Constantinople (modern day Istanbul);[54] the explosion missed its target by a few minutes. One of Dashnaksutiun's founders Kristapor Mikaelian was killed by an accidental explosion during the planning of the operation.

Young Turk Revolution (1908–14)

Two of the largest revolutionary groups trying to overthrow Sultan Abdul Hamid II had been the ARF and the Committee of Union and Progress, a group of mostly European-educated Turks.[62] In a general assembly meeting in 1907, the ARF acknowledged that the Armenian and Turkish revolutionaries had the same goals. Although the Tanzimat reforms had given Armenians more rights and seats in the parliament, the ARF hoped to gain autonomy to govern Armenian populated areas of the Ottoman Empire as a "state within a state". The "Second congress of the Ottoman opposition" took place in Paris, France, in 1907. Opposition leaders including Ahmed Riza (liberal), Sabahheddin Bey, and ARF member Khachatur Maloumian attended. During the meeting, an alliance between the two parties was officially declared.[62][63] The ARF decided to cooperate with the Committee of Union and Progress, hoping that if the Young Turks came to power, autonomy would be granted to the Armenians.

In 1908, Abdul Hamid II was overthrown during the Young Turk Revolution, which launched the Second Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire. Dashnaktsutiun became a legal political party and Armenians gained more seats in the 1908 parliament, but the reforms fell short of the greater autonomy that the ARF had hoped for. The Adana massacre in 1909 also created antipathy between Armenians and Turks, and the ARF cut relations with the Young Turks in 1912.[63] Between December 1912 and 1914 ARF politicians held negotiations with the CUP about political reforms in the eastern provinces. The Armenians had the support of the Russians and the CUP accused the Armenians that their actions caused further division between Turks and Armenians.[64]

World War I and the Armenian Genocide

In 1915, Dashnak leaders were deported and killed alongside other Armenian intellectuals during a purge by Ottoman officials against the leaders of the empire's Armenian communities.[65] The ARF, maintaining its ideological commitment to a "Free, Independent, and United Armenia", led the defense of the Armenian people during the Armenian Genocide, becoming leaders of the successful Van Resistance. Jevdet Bey, the Ottoman administrator of Van, tried to suppress the resistance by killing two Armenian leaders (Ishkhan and Vramian) and trying to imprison Aram Manukian, who had risen to fame and gained the nickname "Aram of Van".[66] Moreover, on 19 April, he issued an order to exterminate all Armenians, and threatened to kill all Muslims who helped them.[67]

About 185,000 Armenians lived in Vaspurakan. In the city of Van itself, there were around 30,000 Armenians, but more Armenians from surrounding villages joined them during the Ottoman offensive. The battle started on 20 April 1915, with Aram Manukian as the leader of the resistance, and lasted for two months. In May, the Armenian battalions and Russian regulars entered the city and successfully drove the Ottoman army out of Van.[66] The Dashnaktsutiun was also involved in other less-successful resistance movements in Zeitun, Shabin-Karahisar, Urfa, and Musa Dagh. After the end of the Van resistance, ARF leader Aram Manukian became governor of the Administration for Western Armenia and worked to ease the sufferings of Armenians.

At the end of World War I, members of the Young Turks movement, considered executors of the Armenian Genocide by the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, were assassinated during Operation Nemesis.[68][69]

Republic of Armenia (1918–1920)

As a result of the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917, the Armenian, Georgian, and Azerbaijani leaders of the Caucasus united to create the Transcaucasian Federation in the winter of 1918. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk had drastic consequences for the Armenians: Turkish forces reoccupied Western Armenia. The federation lasted for only three months, eventually leading to the proclamation of the Republics of Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan. The negotiators for Armenia were from the ARF.[70]

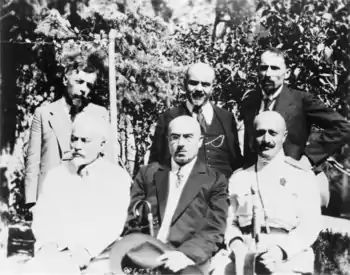

Sitting: Avetik Sahakyan, Alexander Khatisyan, General Christophor Araratov. Standing: Nikol Aghbalian, A. Gulkandanian, S. Araradian.

With the collapse of the Transcaucasian Federation, the Armenians were left to fend for themselves as the Turkish army approached the capital of Yerevan. At first, fearing a major military defeat and massacre of the population of Armenia, the Dashnaks wanted to evacuate the city of Yerevan. Instead, the Military Council headed by Colonel Pirumian decided that they would not surrender and would confront the Turkish army.[71] The opposing armies met on 28 May 1918, near Sardarapat. The battle was a major military success for the Armenian army as it was able to halt the invading Turkish forces.[72] The Armenians also stood their ground at the Battle of Kara Killisse and at the Battle of Bash Abaran. The creation of the First Republic of Armenia was proclaimed on the same day of the Battle of Sardarapat, and the ARF became the ruling party. However, the new state was devastated, with a dislocated economy, hundreds of thousands of refugees, and a mostly starving population.[71]

The ARF, led by General Andranik, tried several times to seize Shusha (known as Shushi by Armenians), a city in Karabakh. Just before the Armistice of Mudros was signed, Andranik was on the way from Zangezur to Shusha, to control the main city of Karabakh. Andranik's forces got within 42 km (26 mi) of the city when the First World War ended, and Turkey, along with Germany and Austria-Hungary, surrendered to the Allies.[73] British forces ordered Andranik to stop all military advances, assuring him that the conflict would be solved with the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. Andranik, not wanting to antagonize the British, retreated to Goris, Zangezur.[73]

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation had a strong presence in the DRA government. Most of the important government posts, such as prime minister, defence minister and interior minister were controlled by its members.

The DRA wanted to recover the country's economy, and create new rules and regulations, but the situation required it to focus on overcoming widespread hunger in the country. The situation was complicated externally, provoked by Turkish and Azerbaijani Muslim riots. In 1920 the situation in the country became worse, with apparent rapprochement between Soviet Russia and Kemal's Turkey. When the Turkish-Armenian war started in autumn 1920, Armenia was isolated and abandoned by Western allies. The newly formed League of Nations did not provide any help. Soviet Russia intensified its pressure on Armenia. Losing the war, Armenia signed the Treaty of Alexandropol on 2 December 1920, which resulted in the recognition of large territorial losses to Turkey. The Armenia military-revolutionary committee formed in Soviet Azerbaijan. Despite their tight grip on power, the ARF ceded power to the Communist Red Army troops invading from the north, which culminated with a Soviet takeover.[38] The ARF was banned, its leaders exiled, and many of its members dispersed to other parts of the world.[38]

Exile

After the communists took over the short-lived First Republic of Armenia and ARF leaders were exiled, the Dashnaks moved their base of operations to where the Armenian diaspora had settled. With the large influx of Armenian refugees in the Levant, the ARF established a strong political structure in Lebanon and to a lesser extent, Syria. From 1921 to 1990, the Dashnaktsutiun established political structures in more than 200 states including the USA, where another large influx of Armenians settled.[34]

With political and geographic division came religious division. One part of the Armenian Church claimed it wanted to be separate from the head, whose seat was in Echmiadzin, Armenian SSR. Some Armenians in the US thought Moscow tried to use the Armenian Church to promote Communists' ideas outside the country. The Armenian Church thus separated into two branches, Echmiadzin and Cilician, and started to operate separately. In the US, Echmiadzin branch churches of the Armenian Apostolic Church would not admit members of the ARF. This was one of the reasons why the ARF discouraged people from attending these churches and brought the representatives from a different wing of the church, the Armenian Catholicate of Cilicia, from Lebanon to the US.[74] In 1933, members of ARF were convicted in the assassination of Armenian archbishop Levon Tourian in New York City. Prior to his murder, the archbishop had been accused of being exclusively pro-Soviet by the ARF.[75] The ARF was legally exonerated from any direct complicity in the assassination.[76]

During World War II, some Berlin-based ARF members saw an opportunity to remove Soviet control from Armenia by supporting the Nazis. The Armenian Legion, composed largely of former Soviet Red Army POWs, was led by Drastamat Kanayan. It participated in the occupation of the Crimean Peninsula[77] but was later based in the Netherlands and France a result of Adolf Hitler's distrust of their loyalty.

During the 1950s, tensions arose between the ARF and Armenian SSR. The death of Catholicos Garegin of the Holy See of Cilicia prompted a struggle for succession. The National Ecclesiastic Assembly, which was largely influenced by the ARF, elected Zareh of Aleppo. This decision was rejected by the Echmiadzin-based Catholicos of All Armenians, the anti-ARF coalition, and Soviet Armenian authorities. Zareh extended his administrative authority over a large part of the Armenian diaspora, furthering the rift that had already been created by his election.[57] This event split the large Armenian community of Lebanon, creating sporadic clashes between the supporters of Zareh and those who opposed his election.[57]

Religious conflict was part of a greater conflict that raged between the two "camps" of the Armenian diaspora. The ARF still resented the fact that they were ousted from Armenia after the Red Army took control, and the ARF leaders supported the creation of a "Free, Independent, and United Armenia", free from both Soviet and Turkish hegemony. The Social Democrat Hunchakian Party and Ramgavar Party, the main rivals of the ARF, supported the newly established Soviet rule in Armenia.[57]

Lebanon

| Year | Mandates | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1943 | 1 / 55 | ||

| 1947 | 2 / 55 | ||

| 1951 | 2 / 77 | ||

| 1953 | 1 / 44 | ||

| 1957 | 2 / 66 | ||

| 1960 | 4 / 99 | ||

| 1964 | 4 / 99 | ||

| 1968 | 4 / 99 | ||

| 1972 | 1 / 99 | ||

| 1992 | 1 / 128 | ||

| 1996 | 1 / 128 | ||

| 2000 | 2 / 128 | ||

| 2005 | 2 / 128 | ||

| 2009 | 3 / 128 | ||

| 2018 | 3 / 128 | ||

From 1923 to 1958, conflicts erupted among Armenian political parties struggling to dominate and organize the diaspora. The ARF and Hunchakian parties struggled in 1926 for control of the newly established shanty-town of Bourj Hammoud in Lebanon; ARF member Vahan Vartabedian was assassinated. The assassination of Hunchakian members Mihran Aghazarian and S. Dekhrouhi followed in 1929 and 1931 respectively.[78] In 1956, when Bishop Zareh was consecrated Catholicos of Cilicia, the Catholicos of Echmiadzin refused to recognize his authority. This controversy polarized the Armenian community of Lebanon. As a result, in the context of the Lebanese civil strife of 1958, an armed conflict erupted between supporters (the ARF) and opponents (Hunchakians, Ramgavars) of Zareh.[57]

Prior to the Lebanese Civil War of 1975–90, the party was closely allied to the Phalangist Party of Pierre Gemayel and generally ran joint tickets with the Phalangists, especially in Beirut constituencies with large Armenian populations.[79] The refusal of the ARF, along with most Armenian groups, to play an active role in the civil war, however, soured relations between the two parties, and the Lebanese Forces (a militia dominated by Phalangists and commanded by Bachir Gemayel, Pierre Gemayel's son), responded by attacking the Armenian quarters of many Lebanese towns, including Bourj Hammoud.[79] Many Armenians affiliated with the ARF took up arms voluntarily to defend their quarters. In the midst of the Lebanese civil war, the shadowy guerrilla organization Justice Commandos of the Armenian Genocide emerged and carried out assassinations from 1975 to 1983. The guerrilla organization has sometimes been linked to the Dashnaks.[80]

Ethnic Armenians are allocated six seats in Lebanon's 128-member National Assembly. The Lebanese branch of the ARF has usually controlled a majority of the Armenian vote and won most of the ethnic Armenian seats in the National Assembly. A major change occurred in the parliamentary election of 2000. With a rift between ARF and the Mustaqbal (Future) party of Rafik Hariri and the ARF was left with only one parliamentary seat, its worst result in many decades. The ARF called for a boycott of the 2005 Beirut elections. Relations soured further when on 5 August 2007 by-election in the Metn district, which includes the predominantly Armenian area of Bourj Hammoud, ARF decided to support Camille Khoury, the candidate backed by opposition leader Michel Aoun's Free Patriotic Movement against Phalangist leader Amine Gemayel and subsequently won the seat. In the 2009 Lebanese general elections, the ARF won 2 seats in parliament which it holds presently. In June 2011, a new Lebanese government was formed where ARF party members were appointed to two ministerial positions, including Ministry of Industry, as part of the March 8 alliance.

The ARF Lebanon branch is headquartered in Bourj Hammoud in the Shaghzoian Centre, along with the ARF Lebanon Central Committee's Aztag Daily newspaper and "Voice Of Van" 24-hour radio station.[81]

Syria

During the French Mandate and under the parliamentary régime in Syria, there were reserved seats for the various religious communities, like in Lebanon, including for Armenians. This system is unofficially still living. Even when they didn't take part as such in elections, Armenian parties such as Dashnak exerted an influence on them.[82][83][84][85]

Independent Armenia

The ARF has always maintained its ideological commitment to "a Free, Independent, and United Armenia".[86] The term United Armenia refers to the borders of Armenia recognized by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and outlined in the Treaty of Sèvres.[87] After Armenia fell under Soviet control in 1920, the ARF within the Armenian diaspora opposed Soviet rule over Armenia and rallied in support of Armenian independence. It contributed to organizing a social and cultural framework aimed at preserving the Armenian identity.[88] However, because of tight communist control, the ARF could not operate in the Armenian SSR and the political party remained banned until 1991.

When independence was achieved in 1991, the ARF soon became one of the major and most active political parties, rivaled mainly by the Pan-Armenian National Movement. Subsequently, on 28 December 1994, President Levon Ter-Petrosyan in a famous television speech banned the ARF, which was the nation's leading opposition party, along with Yerkir, the country's largest daily newspaper.[89] Ter-Petrosyan introduced evidence that supposedly detailed a plot hatched by the ARF to engage in terrorism against his administration, endanger Armenia's national security and overthrow the government. Throughout the evening, government security forces arrested leading ARF figures, and police seized computers, fax machines, files and printing equipment from ARF offices. In addition to Yerkir, government forces also closed several literary, women's, cultural, and youth publications.[89] Thirty-one men, who would later be known as the "Dro Group" (named after the Dro Committee, the group that was allegedly behind the plot), were arrested.

Gerard Libaridyan, an historian and close adviser of Ter-Petrosyan, collected and presented the evidence against the defendants. He later stated in an interview that he was unsure if the evidence was true, inviting the notion that the party was banned because of its increasing chances of winning seats in the July 1995 parliamentary elections.[90] Several months after the elections, most of the men were found not guilty with the exception of several defendants charged for engaging in corrupt business practices. The ban on the party was lifted, however, less than a week after Ter-Petrosyan fell from power in February 1998 and was replaced by Robert Kocharyan, who was backed by the Dashnaks.[38]

However, the ARF members Arsen Artsruni and Armenak Mnjoyan were arrested,[91][92] and Mnjoyan died while in prison in early 2019.

In 2007, the ARF was not part of but had a cooperation agreement in place with the governing coalition, which consisted of two parties in the government coalition, the Republican Party and Prosperous Armenia Party. The Country of Law party was also a member of the governing coalition until it pulled out in May 2006. With 16 of the 131 seats in the National Assembly of Armenia, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation is the major socialist party in Armenia and the third-largest party in parliament.

In addition to its parliamentary seats, the following governmental ministries were also headed by ARF members: Ministry of Agriculture, Davit Lokian;[93] Ministry of Education and Science, Levon Mkrtchian;[94] Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, Aghvan Vardanian;[95] Ministry of Healthcare, Norair Davidian.[96] On 13 July 2007, the ARF History Museum was inaugurated in Yerevan, displaying the history of the party and of its notable members.

In 2007, the ARF announced that it would nominate its own candidate to run for president of Armenia in the February 2008 presidential election. In an innovation on 24–25 November 2007, the ARF conducted a non-binding Armenia-wide primary election. They invited the public to vote to advise the party which of two candidates, Vahan Hovhannisyan and Armen Rustamyan, they should formally nominate for president of Armenia in the subsequent official election. What characterized it as a primary instead of a standard opinion poll was that the public knew of the primary in advance, all eligible voters were invited, and the voting was by secret ballot. Nearly 300,000 people voted in makeshift tents and mobile ballot boxes. Vahan Hovhannisyan received the most votes and was subsequently nominated for the presidential election by the ARF Supreme Council in a secret ballot.[97] In the presidential election, Hovhannisyan placed fourth with 6.2% of the vote.[98] In 2008, ARF re-joined the ruling political coalition in Armenia[40] and supported strong police actions during the 2008 Armenian presidential election protests that led to ten deaths.

Due to the signature of the so-called Zurich Protocols the ARF left the coalition and became an opposition party once again in 2009, but relations with other factions in the Armenian opposition have remained frosty.[99] In 2012 parliamentary election the ARF won 5 seats losing 11 parliamentary seats from 2007.

ARF then reentered Sargsyan's cabinet in February 2016, obtaining three ministerial posts: Ministry of Economy, Local Government and Education; also as a result of what was defined as a "long-term political cooperation" agreement with the Republican Party, ARF also got to appoint the regional governors of Aragatsotn and Shirak Provinces.[41]

After the 2016 Nagorno-Karabakh clashes, the ARF helped the Ministry of Defense of Armenia in setting up a volunteer reserve battalion, made up mostly of party members. This unit, made up of experienced commanders and soldiers, some of them veterans from the Nagorno-Karabakh war, is one of the newest units of the Armenian military. It traces back its heritage from the Shushi independent battalion of the previous war, and is simply called the "ARF battalion".[100]

The party scored well at the 2017 election, winning 7 seats at the National Assembly with 6,58% of the votes, mostly due to the great management of the ministries and provinces under its control.

Following the start of the Armenian Velvet Revolution, ARF broke its coalition with the Republican Party and moved into opposition; later on, the party supported Nikol Pashinyan's new cabinet. The election of 2018 saw the collapse of the party, only scoring 3,89% of the votes and winning no seats; it was the first time since the Independence of Armenia that ARF had no representation in the National Assembly.

Since its loss in the election, the ARF has become the main reasonable extra parliamentary opposition party to the Pashinyan government, criticizing it mainly because of its right-wing economic and social policies, like the introduction of 20% flat tax by the government, the elimination of tax brackets, wanting to change the National anthem of Armenia, etc.

The ARF also gained popularity by intensifying its social aid programs to those in need in Armenia, especially in the rural areas. The party has provided aid to locals during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, mainly thanks to various donation made by members of the Armenian diaspora.

During the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War, the ARF again formed volunteer battalions to fight in the war.[101] After the conclusion of the war, the party formed a coalition with 16 other political parties (most notably the former ruling Republican Party and the parliamentary opposition party Prosperous Armenia) calling itself the "Homeland Salvation Movement", calling on Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan to resign for the defeat of the Armenian side in the war. Along with the other parties in the coalition, the ARF currently supports former prime minister Vazgen Manukyan as their candidate for prime minister. The "Homeland Salvation Movement" has attempted to force Pashinyan's resignation through the organization of mass protests.[102]

Electoral record

In the 2000s, the party usually garnered some 10 to 15 percent of the vote in national elections.[103] In a 2007 confidential telegram Anthony Godfrey, U.S. Embassy in Armenia chargé d'affaires, wrote that the party "has had a historically loyal following of 10 to 12 percent of the population, but probably has little chance to expand from that base."[104] Following the 2018 Armenian Velvet Revolution, the party polled at 1–2%.[105][106][107] The ARF, for the first time since 1999, did not win seats in the parliament and effectively became extra-parliamentary opposition.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Artsakh

| National Assembly of Artsakh | |||||||||

| Year | Party-list | Constituency /total | Total seats | +/– | |||||

| Votes | % | Seats /total | |||||||

| 1995 | / | / | /33 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | % | / | / | 9 / 33 |

|||||

| 2005 | 14,534 | 24.4% | / | / | 3 / 33 |

||||

| 2010 | 12,725 | 19.1% | 4 / 17 |

2 / 16 |

6 / 33 |

||||

| 2015 | 12,965 | 18.81% | 4 / 22 |

3 / 11 |

7 / 33 |

||||

After the Soviet Union expanded into the South Caucasus, it established the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) within the Azerbaijan SSR in 1923.[111][112][113] In the final years of the Soviet Union, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation established a branch in Nagorno-Karabakh. In January 1991, the Dashnaktsutiun won the parliamentary election and governed as the ruling party during the entirety of the Nagorno-Karabakh war.[114] The Dashnaks actively supported the independence of Nagorno-Karabakh (or Artsakh as Armenians call it). It aided the Nagorno-Karabakh Defense Army by sending armed volunteers to the front lines and supplying the army with weapons, food, medicine and moral support.[115] The party even had its own infantry battalion, subordinated to NKR army command, the "Shushi independent battalion", which became one of the most efficient Armenian units during the war. After deciding not to run in the second parliamentary elections, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation ran in the 1999 elections and won 9 of the 33 seats in the National Assembly of Nagorno Karabakh.[114] At the June 2005 elections, the Dashnaktsutiun was part of an electoral alliance with Movement 88 that won 3 out of 33 seats. Following the March 2020 elections, the party won 3 seats in the National Assembly.

Ideology and goals

The principal founders of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation were nationalist,[116] socialists, and Marxist elements were omnipresent in the introductory section of the party's first program written by Rosdom, entitled "General Theory".[117] The ARF first set down its ideological and political goals during the Hamidian regime. It denounced the Ottoman regime and the unbearable conditions of life for its Armenians and advocated changing the regime in power and securing more rights through revolution and armed struggle. The ARF had and still has socialism within its political philosophy. Its program expresses the entire, multifaceted make-up of the Armenian revolutionary movement, including its national-liberation, political, and social-economic aspects.[118]

Despite subsequent modifications, the above-mentioned principles and tendencies continue to characterize the ideological world of the Dashnaktsutiun, and its approach toward issues has remained unchanged. In recent decades, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation reasserted itself ideologically and reformulated the section of its program called "General Theory", adapting it to current concepts of socialism, democracy and rights of self-determination.[118] The party has long supported a parliamentary republican political system and campaigned for a "yes" vote in the 2015 constitutional referendum.[119][120]

Its primary goals are:

- Creation of a free, independent, and united Armenia. The borders of United Armenia shall include all territories designated as Armenia by the Treaty of Sèvres as well as the regions of Artsakh, Javakhk, and Nakhichevan (See map).[39]

- International condemnation of the Genocide committed by the Ottoman Empire against the Armenians, return of the lands which are occupied, and just reparations to the Armenian nation[39]

- The gathering of worldwide expatriate Armenians on the lands of United Armenia.[39]

- Strengthening Armenia's statehood, institutionalization of democracy and the rule of law, securing the people's economic well-being, and establishment of social justice, and a democratic and socialistic independent republic in Armenia[39]

The ARF is often accused of having a present strategy that does not differ from the one used during the time of the Ottoman Empire. Its tactics are viewed as still being aimed at convincing Western governments and diplomatic circles to sponsor the party's demands.[121]

In 1907, the Dashnaktsutiun joined the Second International until its dissolution during World War I.[122] It later joined the reformed Socialist International and remained a full member until 1960, when it decided to pull out of the organization.[123] In 1996, it was re-accepted as an observer member, and in 1999 the Dashnaks earned full membership in the international organization.[123] The party was also a member of the Labour and Socialist International between 1923 and 1940.[124]

A member of the ARF is called Dashnaktsakan (in Eastern Armenian) or Tashnagtsagan (in Western Armenian), or Dashnak/Tashnag for short. Other than calling each other by name, members formally address one another as Comrade (Ընկեր or Unger for boys and men, Ընկերուհի or Ungerouhi for girls and women).[125]

The party is also generally pro-European and supports the European integration of Armenia. The party is in favor of Armenia's continued political association and economic integration with the European Union.[126]

Affiliate organizations

The ARF is considered the foremost organization in the Armenian diaspora, having established numerous Armenian schools, community centers, Scouting and athletic groups, relief societies, youth groups, camps, and other organs throughout the world.[34]

The ARF also works as an umbrella organ for the Armenian Relief Society, the Homenetmen Armenian General Athletic Union, the Hamazkayin Cultural Foundation, and many other community organizations.[34] It operates the Armenian Youth Federation, which encourages the youth of the diaspora to join the political cause of the ARF and the Armenian people.

The ARF Shant Student Association and the ARF Armen Karo Student Association are organizations of college and university students on various campuses and are the only ARF organizations whose membership is exclusively from this group.

US and Canada

Armenian National Committee of America, an ARF-affiliate organization, is the strongest Armenian lobby organization in the United States.[127] Its sister organization Armenian National Committee of Canada, operates in Canada as the strongest and most influential Armenian-Canadian organization.[128]

Other countries

Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Cyprus, Egypt, England, France, Georgia, Greece, Iran, Israel, Lebanon, Russia, Switzerland, Syria, The Netherlands and Uruguay subsequently have played a significant role in the campaign for the recognition of the Armenian Genocide in their respective countries.[129]

Media

ARF and its affiliate organizations worldwide publish 12 newspapers: 4 daily and 8 weekly. Also, there are two TV channels, including one online. Two radio stations are aired everyday, including one online.

- Periodicals

| Name (in Armenian) | Type | Date est. | Location | Language(s) | Website |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yerkir (Երկիր) | weekly | 1991 | Eastern Armenian | www | |

| Aparaj (Ապառաժ) | weekly | Eastern Armenian | aparaj | ||

| Alik (Ալիք) | daily | 1931 | Eastern Armenian | alikonline | |

| Housaper (Յուսաբեր) | daily | 1913 | Western Armenian | ||

| Aztag (Ազդակ) | daily | 1927 | Western Armenian | www | |

| Asbarez (Ասպարէզ) | daily | 1908 | Western Armenian, English | asbarez | |

| Hairenik (Հայրենիք) | weekly | 1899 | Western Armenian | hairenikweekly | |

| Armenian Weekly | weekly | 1934 | English | armenianweekly | |

| Haytoug (Հայդուկ) | youth magazine (AYF) | 1978 | Western Armenian, English | www | |

| Horizon (Հորիզոն) | weekly | 1979 | Western Armenian, English, French | horizonweekly | |

| Ardziv (Արծիւ) | youth magazine (AYF) | 1991 | Western Armenian, English, French | ardziv | |

| Artsakank (Արձագանգ) | weekly | Western Armenian, English | www | ||

| Azat Or (Ազատ Օր) | weekly | 1945 | Western Armenian, Greek | azator | |

| Kantsasar (Գանձասար) | weekly | 1978 | Western Armenian | www | |

| Armenia (Արմենիա) | weekly | 1931 | Western Armenian, Spanish | diarioarmenia |

- Television

| Name | Date established | Location | Language(s) | Website |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yerkir Media (Երկիր Մեդիա) | 2003 | Armenian | www | |

| Horizon TV (online only) | Armenian, English | www | ||

| Nor Hai Horizon TV | 1993 | Armenian, English | www | |

- Radio

| Name | In Armenian | Type | Date established | Location | Language(s) | Circulation | Website |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voice of Van | Վանայ Ձայն | radio station | 1927 | Armenian | — | www | |

| Azat Alik | Ազատ Ալիք | online radio station | Armenian | — | web | ||

| Radio Yeraz | Ռատիո Երազ | online radio station | 2011 | Armenian | first Armenian online radio station in Syria | www www |

See also

References

- Notes

- Reformed spelling: Հայ Յեղափոխական Դաշնակցություն; Eastern Armenian pronunciation: Hay Heghapokhagan Dashnaktsutyun; Western Armenian pronunciation: Hay Heghapokhagan Tashnagtsutiun. The abbreviation in both cases is written as ՀՅԴ which is pronounced as Ho-Yi-Da in Eastern and Ho-Hi-Ta in Western Armenian.

- Eastern Armenian: Դաշնակցություն, Dashnaktsutyun; Western Armenian: Դաշնակցութիւն, Tashnagtsoutioun

- Sources

- Libaridian, Gerard J. (2004). Modern Armenia: People, Nation, State. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7658-0205-7.

- "Յուրաքանչյուր երկրորդ չափահաս հայաստանցին կուսակցակա՞ն [Every second Armenian a party member?]". Tert.am (in Armenian). Yerevan. 15 May 2012. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

...իսկ ՀՅԴ գերագույն մարմնի անդամ Սպարտակ Սեյրանյանի խոսքով փետրվարի վերջի տվյալներով կուսակցության անդամների թիվը կազմել է 6800:

- "Armenia: Internal Instability Ahead" (PDF). Yerevan/Brussels: International Crisis Group. 18 October 2004. p. 8. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

The Dashnaktsutiun Party, which has a major following within the diaspora, states as its goals: "The creation of a Free, Independent, and United Armenia. The borders of United Armenia shall include all territories designated as Armenia by the Treaty of Sevres as well as the regions of Artzakh [the Armenian name for Nagorno-Karabakh], Javakhk, and Nakhichevan".

- Harutyunyan, Arus (2009). Contesting National Identities in an Ethnically Homogeneous State: The Case of Armenian Democratization. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Western Michigan University. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-109-12012-7.

The ARF strives for the solution of the Armenian Cause and formation of the entire motherland with all Armenians. The party made it abundantly clear that historical justice will be achieved once ethnic Armenian repatriate to united Armenia, which in addition to its existing political boundaries would include Western Armenian territories (Eastern Turkey), Mountainous Karabagh and Nakhijevan (in Azerbaijan), and the Samtskhe-Javakheti region of the southern Georgia, bordering Armenia.

- "Armenian Nationalist Party Threatens President Over Turkey Protocols". Yerevan. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 14 January 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- Cornell, Svante E. (2011). Azerbaijan Since Independence. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe. p. 11. ISBN 9780765630049.

Drawn equally to nationalism, the ARF...

- Abbasov, Shahin (15 October 2010). "Azerbaijan: Baku Reaches Out to Armenian Hard-liners in Karabakh PR Bid". EurasiaNet. New York. Open Society Institute. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

...Armenian Revolutionary Federation-Dashnaktsutiun, a nationalist Armenian party...

- "The first numbers of the lists of eleven political forces presented their visions of the fight against corruption and economic development" Տասնմեկ քաղաքական ուժերի ցուցակների առաջին համարները ներկայացրին կոռուպցիայի դեմ պայքարի ու տնտեսության զարգացման իրենց տեսլականները (in Armenian). Armenpress. 5 December 2018. Archived from the original on 9 November 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

Տնտեսության վերաբերյալ՝ տնտեսական մեր կարգը սոցիալական-շուկայական տնտեսությունն է՝ Սահմանադրությամբ: Սա է պետք կյանքի կոչել»,- ասաց ՀՅԴ ցուցակի առաջին համար Արմեն Ռուստամյանը:

- "It is necessary to get rid of the phrase 'there are no means, there can be no reforms.' Armen Rustamyan" Պետք է ձերբազատվել «չկան միջոցներ, չեն կարող լինել բարեփոխումներ» ձևակերպումից. Արմեն Ռուստամյան. Yerkir (in Armenian). 16 September 2017. Archived from the original on 9 November 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

Իրապես սոցիալական շուկայական տնտեսությունը ենթադրում է շուկայի կարգավորում:

- Kalantarian, Karine (25 November 2009). "Dashnaks Explain Criticism Of Russia". azatutyun.am. RFE/RL. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020.

...the traditionally pro-Russian party...

- Danielyan, Emil (16 December 1995). "ARMENIA: Banned Opposition Party Has Deep Roots". Azg. Transitions Online. Archived from the original on 4 July 2020. "...the virulently anti-Turkish party..." [...] "The pro-Russian and pro-socialist Dashnak party... [...] The Dashnaks were opposed to Armenian independence from the USSR, and they slammed the government over its initial refusal to participate in discussions on a new union treaty initiated under Mikhail Gorbachev's leadership."

- Bedevian, Astghik; Stepanian, Ruzanna (4 December 2014). "Armenian Parliament Backs Eurasian Union Entry". azatutyun.am. RFE/RL. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020.

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutyun), another major opposition party, said joining the EEU is critical for Armenia's national security.

- Stepanian, Ruzanna (1 September 2010). "Dashnaks Back New Russian-Armenian Pact". azatutyun.am. RFE/RL. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020.

- "Դաշնակցության սոցիալիզմի մոդելը [The Socialist Model of Dashnaktsutyun]". parliamentarf.am (in Armenian). Armenian Revolutionary Federation faction in the National Assembly of the Republic of Armenia. 9 July 2011. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- "Evaluation Report on Armenia on Transparency of party funding" (PDF). Strasbourg: Council of Europe. 3 December 2010. p. 5.

Armenian Revolutionary Federation Party (ARF, socialist)

- "Where is the Armenian LEFT, the true alternative?". Yerevan: Institute for Democracy and Human Rights (IDHR). 10 December 2007. Archived from the original on 7 September 2014.

Armenian Revolutionary Federation, ARF: For almost nine years they have been party, ally or auxiliary to the neo-liberal capitalist authorities in the Third Republic of Armenia. They deny, avoid, and deviate from the socialist roots that are so indispensable for the survival and development of our people, nation and state for the sake of pragmatism, real-politik, the result of which is degeneration. They also reinforce neo-liberalism in Armenia.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1971). "Russian Armenia. A Century of Tsarist Rule". Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas. Franz Steiner Verlag. 19 (1): 40. JSTOR 41044266.

- Verluise, Pierre (1995). Armenia in Crisis: The 1988 Earthquake. Wayne State University Press. p. 38. ISBN 9780814325278.

Although socialism played an important part in party ideology in its early years, the ARF after 1920 became an outspoken nationalist critic of Soviet Armenia.

- Goltz, Thomas (2015) [1998]. Azerbaijan Diary: A Rogue Reporter's Adventures in an Oil-rich, War-torn, Post-Soviet Republic. Routledge. p. 314. ISBN 9780765602442.

Suppressed or expelled from Soviet Armenia, the Dashnaks became the most visible and resonant anti-Communist opposition group in the Armenian diaspora for the next seventy years.

- Panossian, Razmik (2006). The Armenians: From Kings and Priests to Merchants and Commissars. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 365. ISBN 9780231139267.

The ARF thus came to associate its nationalism with anti-communism...

- "ARF Joins Party of European Socialists as Observer Member". Armenian Weekly. 16 June 2015.

- "ARF news 'Yerkir', Hrant Markarian Speech". Archived from the original on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- Verluise, Pierre (1995). Armenia in crisis: the 1988 earthquake. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 38. ISBN 9780814325278.

- "Report on Armenia's Parliamentary Election May 30, 1999". Washington, D.C.: Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe. 1 September 1999. p. 7. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015.

Armenian Revolutionary Federation: Founded in 1890, the ARF is a nationalist, socialist party...

- Evans, John Marshall (16 June 2005). "Dashnaks Maneuvering For Position". Embassy of the United States of America to Armenia – via WikiLeaks.

The Dashnak Party is a socialist-nationalist party.

- Geukjian, Ohannes (2007). "The Policy of Positive Neutrality of the Armenian Political Parties in Lebanon during the Civil War, 1975–90: A Critical Analysis". Middle Eastern Studies. 43 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1080/00263200601079633. JSTOR 4284524. S2CID 144094304.

the Armenian Revolutionary. Federation or the Dashnak Party, socialist in doctrine, but which remained more of a nationalist party throughout history

- "Armenian Revolutionary Federation". Portal on Central Eastern and Balkan Europe. Bologna, Italy: University of Bologna. Archived from the original on 7 September 2014.

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation is a nationalist-socialist party.

- "Armenian Revolutionary Federation Founded, Armenian history timeline". Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- Sanjian, Ara (2011). "The ARF's First 120 Years". The Armenian Review. 52 (3–4): 1–16. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "Tachnaq party holds 2 seats in Lebanese National Assembly" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 30 December 2006.

- "ARF among parties running in NKR elections". Archived from the original on 3 October 2006. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- Armenian Revolutionary Federation Program (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation in its world outlook and traditions is essentially a socialist, democratic, and revolutionary party.

- "ARFD". ARFD. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- "U.S. Embassy releases study on Armenian-Americans". Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- Nalbandian, Louise (1975). "Armenian Revolutionary Federation, 1890-1896". The Armenian Revolutionary Movement. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. pp. 151–178. ISBN 0-520-00914-2.

- Libaridian, Gerard J. (1996). "Revolution and Liberation in the 1892 and 1907 Programs of the Dashnaktsutiun". In Suny, Ronald Grigor (ed.). Transcaucasia, Nationalism, and Social Change. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 187–198.

- Dasnabedian, Hratch (1990). History of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation Dashnaktsutiun 1890/1924. Milan: Oemme Edizioni. pp. 43–44.

- "ARF.am Home". Archived from the original on 12 October 2006. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- "Goals of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation". Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 29 December 2006.

- "RA Prime Minister Tigran Sargsyan's Speech at General Meeting of ARF "Dashnaktsutyun"". Government of Armenia. 21 May 2008. Archived from the original on 25 June 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- "ARF Signs 'Political Cooperation' Agreement with Government". 24 February 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- "ARF's Supreme Council Approves Nomination of Serzh Sargsyan for Prime Minister". Hetq. 23 April 2018.

- Geifman, Anna (31 December 1995). Thou Shalt Kill: Revolutionary Terrorism in Russia, 1894–1917. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-691-02549-0.

- Vratsian, Simon (2000). Tempest-Born DRO. Armenian Prelacy, New York, translated by Tamar Der-Ohannesian. pp. 13–22.

- ""A Critical Survey of Bolshevism" – Stalin". Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- Swietochowski, Tadeusz (1985). Russian Azerbaijan, 1905–1920. The Shaping of a National Identity in a Muslim Community. Cambridge University Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-521-52245-8.

- Libaridian, Gerard J. (31 December 1995). Modern Armenia: People, Nation, State. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-691-02549-0.

- (in Russian)«Всеподданейшая записка по управлению кавказским краем генерала адьютанта графа Воронцова-Дашкова», СПб.: Государственная Тип., 1907, с.12

- Suny, Ronald (1996). Transcaucasia, Nationalism, and Social Change: Essays in the History of Armenia, 2nd edition. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-0-472-06617-9.

- Abraham, Richard (1990). Alexander Kerensky: The First Love of the Revolution. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-231-06109-4.

- Abraham. Alexander Kerensky, p. 54

- Berberian, Houri (2001). Armenians and the Iranian Constitutional Revolution of 1905–1911. Westview Press. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-0-8133-3817-0.

- Berberian, Houri (2001). Armenians and the Iranian Constitutional Revolution of 1905–1911. Westview Press. pp. 132–134. ISBN 978-0-8133-3817-0.

- Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1996). Hayots Badmoutioun (Armenian History) (in Armenian). Hradaragutiun Azkayin Oosoomnagan Khorhoortee, Athens Greece. pp. 42–48.

- Ministère des affaires étrangères, op. cit., no. 212. M. P. Cambon, Ambassadeur de la Republique française à Constantinople, ŕ M. Hanotaux, Ministre des affaires étrangères, p. 239; et no. 215 p. 240.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1997). The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 224–225. ISBN 978-0-312-10168-8.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1997). The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 418. ISBN 978-0-312-10168-8.

- "Khanasor Expedition, Armenian history timeline". Retrieved 26 December 2006.

- Karentz, Varoujan (2004). Mitchnapert the Citadel: A History of Armenians in Rhode Island. iUniverse. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-595-30662-6.

- Mesrobian, Arpena S. (2000). Like One Family: The Armenians of Syracuse. Gomidas Institute. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-9535191-1-8.

- Pasdermadjian, Garegin (1918). Why Armenia Should be Free: Armenia's Rôle in the Present War (PDF). Hairenik Pub. Co.

- Kansu, Aykut (1997). The Revolution of 1908 in Turkey. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 78. ISBN 978-90-04-10283-5.

- Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1996). Hayots Badmoutioun (Armenian History) (in Armenian). Hradaragutiun Azkayin Oosoomnagan Khorhoortee, Athens Greece. pp. 52–53.

- Kevorkian, Raymond (30 March 2011). The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. I.B.Tauris. pp. 158–165. ISBN 978-0-85773-020-6.

- "Eyewitness account of the start of the Armenian Genocide". Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1996). Hayots Badmoutioun (Armenian History) (in Armenian). Hradaragutiun Azkayin Oosoomnagan Khorhoortee, Athens Greece. pp. 92–93.

- Ussher, Clarence D (1917). An American Physician in Turkey. Boston. p. 244.

- "Punishment of the Executors of the Armenian Genocide". Archived from the original on 11 December 2006. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- Avakian, Lindy V. (1989). The Cross and the Crescent. USC Press. ISBN 978-0-943247-06-9.

- "Transcaucasian Federation". Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- "The First Republic". Archived from the original on 19 December 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- "Genocide survivors recall victory at Sardarapat". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 30 December 2006.

- "Pre-Soviet history of Karabakh". Retrieved 30 December 2006.

- "Soviet background separates two Armenian churches in US". Archived from the original on 30 June 2007. Retrieved 28 June 2007.

- Atabaki & Mehendale, Touraj & Sanjyot (2005). Central Asia And The Caucasus: Transnationalism And Diaspora. Routledge (UK). pp. 136. ISBN 978-0-415-33260-6.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1997). The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 416. ISBN 978-0-312-10168-8.

- Auron Yuri, The Banality of Denial, p. 238

- Weinberg, Leonard (1992). Political parties and terrorist groups. Routledge (UK). p. 19. ISBN 978-0-7146-3491-3.

- Federal Research, Division (2004). Lebanon a Country Study. Kessinger Publishing. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-4191-2943-8.

- Verluise, Pierre (April 1995), Armenia in Crisis: The 1988 Earthquake, Wayne State University Press, p. 143, ISBN 978-0-8143-2527-8

- "Tashnag says offers of compromise were snubbed". Retrieved 8 August 2007.

- "The Arab-American handbook: a guide to the Arab, Arab-American & Muslim worlds", Nawar Shora. Cune Press, 2008. ISBN 1-885942-47-8, ISBN 978-1-885942-47-0. p. 261

- Albert H. Hourani, Minorities in the Arab World, London, Oxford University Press, 1947 ISBN 0-404-16402-1

- Claude Palazzoli, La Syrie – Le rêve et la rupture, Paris, Le Sycomore, 1977 ISBN 2-86262-002-5

- Nikolaos van Dam, The Struggle For Power in Syria: Politics and Society Under Asad and the Ba'th Party, London, Croom Helm, 1979 ISBN 1-86064-024-9

- "ARF Shant Student Association". Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- "Treaty of Sèvres". Archived from the original on 6 January 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- "Armenian Revolutionary Federation – Dashnaktsutiun". Archived from the original on 14 March 2007. Retrieved 3 February 2007.

- "ARF newspaper banned". Archived from the original on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- Interview in 2001 by Aram Abrahamyan on Horizon Armenian Programming.

- "Վճիռ ցմահ դատապարտյալ Արսեն Արծրունու գործով. պատիժը մնաց անփոփոխ". Human Rights Armenia. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- "Արմեն Մնջոյանին մերժել են: Ցմահ ազատազրկվածները դիմում են դատարաններ". Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- "Davit Lokyan profile at Armenian Government website". Archived from the original on 8 December 2006. Retrieved 29 December 2006.

- "Levon Mkrtchian profile at Armenian Government website". Archived from the original on 16 October 2006. Retrieved 29 December 2006.

- "Aghvan Vardanian profile at Armenian Government website". Archived from the original on 16 October 2006. Retrieved 29 December 2006.

- "Norair Davidian profile at Armenian Government website". Archived from the original on 16 October 2006. Retrieved 29 December 2006.

- "ARFD Nominates Vahan Hovhannissian". A1+. 30 November 2007. 18 December 2007.

- "Ra Cec Declared Serge Sargsian Armenia's President", defacto.am, 25 February 2008.

- "Dashnaks Skeptical About Sarkisian's Dialogue With Ter-Petrosian". Azatutyun. 28 April 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- https://araratnews.am/hyd-n-kazmavorum-e-kamavorakanneri-pahestayin-gumartak/

- "More ARF Volunteers Head to Frontlines". Asbarez. 28 October 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- "As Ultimatum Expires, Protests Continue". EVN Report.

- Pennington (6 February 2008). "Presidential Candidate Profile: Vahan Hovanissian (Dashnak Party) – Fighting for the third force mantle". Embassy of the United States of America to Armenia – via WikiLeaks.

...ARF's customary 10–15 percent of votes...

- Anthony Godfrey (4 May 2007). "Armenia Political Party Primer". Embassy of the United States of America to Armenia – via WikiLeaks.

- https://www.iri.org/sites/default/files/2018.11.23_armenia_poll.pdf

- (in Armenian) «Gallap international association»-ը հրապարակեց 17.04–23.04 ժամանակահատվածում անցկացված սոցիոլոգիական հարցումների արդյունքները Archived 30 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Pashinyan's Yelk would get 75% of votes if snap elections were held next Sunday, poll says". ARKA News Agency. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- "Armenia's parliamentary election and constitutional referendum: July 5, 1995". Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe. p. 11.

The most controversial aspect of the election was the banning of the ARF.

- Khachatrian, Ruzanna (25 November 2002). "Dashnaks Endorse Kocharian's Reelection Bid". azatutyun.am. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- "Armen Sarkissian Elected Fourth President of Armenia". civilnet.am. 2 March 2018.

- "The World Factbook – Armenia". CIA. Retrieved 27 January 2007.

- (in Armenian) Լեռնային Ղարաբաղի Ինքնավար Մարզ (ԼՂԻՄ) (Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast) Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia, Vol. 4, Yerevan 1978 p. 576

- de Waal, Thomas (2003). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-1945-9.

- "Electioral history of Karabakh". Archived from the original on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2007.

- Federal Research, Division (2004). Armenia a Country Study. Kessinger Publishing. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-4191-0751-1.

- "The principal founders of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation were nationalist, The ARF's involvement in each of these revolutions was largely a result of the organization's pragmatic world-view arising from the close linkage between national liberation and socialism underpinning its ideology". Archived from the original on 6 January 2006. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- "ARF history". Archived from the original on 2 January 2006. Retrieved 29 January 2006.

- "ARF history (2)". Archived from the original on 6 January 2006. Retrieved 29 January 2006.

- Aslanian, Karlen; Movsisian, Hovannes (24 August 2015). "Constitutional Reform 'Victory For Dashnaktsutyun'". azatutyun.am. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

...Dashnaktsutyun has long favored the country's transformation into a parliamentary republic...

- Hayrumyan, Naira (8 November 2012). "Vote 2013: PAP for "technical" president to carry out constitutional reform". ArmeniaNow.

...the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF Dashnaktsutyun) have long been advocating a transition to a parliamentary form of government...

- Melkonian, Monte (1990). The Right to Struggle: Selected Writings of Monte Melkonian on the Armenian National Question. San Francisco, Sardarabad Collective. pp. 55–57. ISBN 978-0-9641569-1-3.

- Vered Amit, Talai (1989). Armenians in London: the management of social boundaries. Manchester University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7190-2927-1.

- "La F.R.A. Dachnaktsoutioun rejoint l'Internationale Socialiste" (in French). Archived from the original on 4 December 2006. Retrieved 11 March 2006.

- Kowalski, Werner (1985). Geschichte der sozialistischen arbeiter-internationale: 1923 – 19. Dt. Verl. d. Wissenschaften, 1985. p. 335.

- "Spotlight: ANC of Rhode Island". Retrieved 14 March 2007.

- Karentz, Varoujan (2004). Mitchnapert the Citadel: A History of Armenians in Rhode Island. iUniverse. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-595-30662-6.

- "Armenian National Committee of Canada". Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- "ANC Chapters". Bay Area Armenian National Committee. Archived from the original on 19 October 2004. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

Further reading

- Papazian, Kapriel Serope (1934). Patriotism perverted: A discussion of the deeds and the misdeeds of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, the so-called Dashnagtzoutune. Boston: Baikar Press. [a critical publication on the party's history by a Ramgavar author]

- Tololyan, Minas (1962). The crusade against the Armenian Revolutionary Federation. Armenian Research Center collection. Boston: Hairenik Association. [a publication by the ARF]

- Кhudinian, Gevorg (1990). "Հ. Հ. Դաշնակցության գաղափարական ակունքները [High-principled sources of Armenian revolutioiary parly Dashnaktsutjun]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian). № 6 (6): 3–12.

External links

- Official web site – Armenian Revolutionary Federation

- Official English language site – Armenian Revolutionary Federation – Dashnaktsutyun (Armenian Socialist Party)

- Armenian Revolutionary Federation Shant Student Association

- Armenian Revolutionary Federation Archives Institute

- Altintas, Toygun: Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

.svg.png.webp)