Monarchy in Nova Scotia

By the arrangements of the Canadian federation, the Canadian monarchy operates in Nova Scotia as the core of the province's Westminster-style parliamentary democracy.[1] As such, the Crown within Nova Scotia's jurisdiction is referred to as the Crown in Right of Nova Scotia,[2] Her Majesty in Right of Nova Scotia,[3] or the Queen in Right of Nova Scotia.[4] The Constitution Act, 1867, however, leaves many royal duties in Nova Scotia specifically assigned to the sovereign's viceroy, the Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia,[1] whose direct participation in governance is limited by the conventional stipulations of constitutional monarchy.[5]

| Queen in Right of Nova Scotia | |

|---|---|

Provincial/State | |

| |

| Incumbent | |

| |

| Elizabeth II Queen of Canada since 6 February 1952 | |

| Details | |

| Style | Her Majesty |

| First monarch | Victoria |

| Formation | 1 July 1867 |

| Residence | Government House, Halifax |

Constitutional monarchy in Nova Scotia

The role of the Crown is both legal and practical; it functions in Nova Scotia in the same way it does in all of Canada's other provinces, being the centre of a constitutional construct in which the institutions of government acting under the sovereign's authority share the power of the whole.[6] It is thus the foundation of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the province's government.[7] The Canadian monarch—since 6 February 1952, Queen Elizabeth II—is represented and her duties carried out by the Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia, whose direct participation in governance is limited by the conventional stipulations of constitutional monarchy, with most related powers entrusted for exercise by the elected parliamentarians, the ministers of the Crown generally drawn from amongst them, and the judges and justices of the peace.[5] The Crown today primarily functions as a guarantor of continuous and stable governance and a nonpartisan safeguard against the abuse of power.[5][8][9] This arrangement began with the 1867 British North America Act and continued an unbroken line of monarchical government extending back to the late 16th century.[1] However, though Nova Scotia has a separate government headed by the Queen, as a province, Nova Scotia is not itself a kingdom.[10]

Government House in Halifax is owned by the sovereign in her capacity as Queen in Right of Nova Scotia and is used as an official residence both by the lieutenant governor and the sovereign and other members of the Canadian Royal Family will reside there when in Nova Scotia.

Royal associations

Those in the Royal Family perform ceremonial duties when on a tour of the province; the royal persons do not receive any personal income for their service, only the costs associated with the exercise of these obligations are funded by both the Canadian and Nova Scotia Crowns in their respective councils.[11] Monuments around Nova Scotia mark some of those visits, while others honour a royal personage or event. Further, Nova Scotia's monarchical status is illustrated by royal names applied regions, communities, schools, and buildings, many of which may also have a specific history with a member or members of the Royal Family. Associations also exist between the Crown and many private organizations within the province; these may have been founded by a Royal Charter, received a royal prefix, and/or been honoured with the patronage of a member of the Royal Family. Examples include the Royal Nova Scotia International Tattoo, which is under the patronage of Queen Elizabeth II and received its royal prefix from her in 2006.

The main symbol of the monarchy is the sovereign herself, her image (in portrait or effigy) thus being used to signify government authority.[12] A royal cypher or crown may also illustrate the monarchy as the locus of authority, without referring to any specific monarch. Further, though the monarch does not form a part of the constitutions of Nova Scotia's honours, they do stem from the Crown as the fount of honour, and so bear on the insignia symbols of the sovereign.

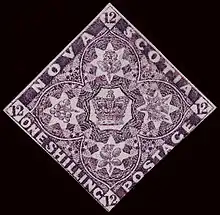

A Nova Scotia stamp issued between 1851 and 1857 bears the royal crown at its centre

A Nova Scotia stamp issued between 1851 and 1857 bears the royal crown at its centre Port Royal, named in honour of King Henry IV

Port Royal, named in honour of King Henry IV

Louisbourg, which derives its name from King Louis XV

Louisbourg, which derives its name from King Louis XV Kingsburg, named for King George III

Kingsburg, named for King George III

Halifax's former Queen Elizabeth High School is named after Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother)

Halifax's former Queen Elizabeth High School is named after Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother)

History

Nova Scotia's first monarchical connections were formed when Jacques Cartier in 1534 claimed Chaleur Bay for King Francis I, though the area was not officially settled until King Henry IV in 1604 established a colony administered by the Governor of Acadia. Only slightly later, King James VI and I laid claim to what is today Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and part of Maine and made it part of the Scottish Crown's dominion, calling the area Nova Scotia.[13][14] James' son, Charles I, later issued the Charter of New Scotland, which created the Baronets of Nova Scotia, many of which continue to exist today. Over the course of the 17th century, the French Crown lost via war and treaties its Maritimes territories to the British sovereign.

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, was sent in 1794 to take command of Nova Scotia, where he, an amateur architect, designed many of Halifax's forts, oversaw the construction of numerous roads, devised a telegraph system, and left an indelible mark on the city in the form of public buildings of Georgian architecture. After he departed in 1800, he remained remembered for his deeds, such as the construction of both St. George's Round Church and the Halifax Town Clock, as well as improvements to the Grand Parade.[15]

For the bicentennial in 1983 of the arrival of the first Empire Loyalists in Nova Scotia, Prince Charles, Prince of Wales, and his wife, Diana, Princess of Wales, attended the celebrations.[16]

See also

References

- Victoria (29 March 1867), Constitution Act, 1867, III.9, V.58, Westminster: Queen's Printer, retrieved 15 January 2009

- Transport Canada (1994), Transport Canada > Safety > Transportation of Dangerous Goods > TDG Act & Regulations > Agreements Respecting Administration of the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act, 1992 > Nova Scotia, Queen's Printer for Canada, retrieved 9 July 2009

- Transport Canada 1994, 18.a

- Elizabeth II (2005), Municipal Funding Agreement (PDF), Halifax: Queen's Printer for Nova Scotia, retrieved 9 July 2009

- MacLeod, Kevin S. (2008). A Crown of Maples (PDF) (1 ed.). Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-662-46012-1. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- Cox, Noel (September 2002). "Black v Chrétien: Suing a Minister of the Crown for Abuse of Power, Misfeasance in Public Office and Negligence". Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law. Perth: Murdoch University. 9 (3): 12. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- Privy Council Office (2008), Accountable Government: A Guide for Ministers and Ministers of State – 2008, Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada, p. 49, ISBN 978-1-100-11096-7, archived from the original on 18 March 2010, retrieved 17 May 2009

- Roberts, Edward (2009). "Ensuring Constitutional Wisdom During Unconventional Times" (PDF). Canadian Parliamentary Review. Ottawa: Commonwealth Parliamentary Association. 23 (1): 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 February 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- MacLeod 2008, p. 20

- Forsey, Eugene (31 December 1974), "Crown and Cabinet", in Forsey, Eugene (ed.), Freedom and Order: Collected Essays, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Ltd., ISBN 978-0-7710-9773-7

- Palmer, Sean; Aimers, John (2002), The Cost of Canada's Constitutional Monarchy: $1.10 per Canadian (2 ed.), Toronto: Monarchist League of Canada, archived from the original on 19 June 2008, retrieved 15 May 2009

- MacKinnon, Frank (1976), The Crown in Canada, Calgary: Glenbow-Alberta Institute, p. 69, ISBN 978-0-7712-1016-7

- Bousfield, Arthur; Toffoli, Garry, Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada, Canadian Royal Heritage Trust, archived from the original on 5 January 2010, retrieved 10 July 2009

- Fraser, Alistair B. (30 January 1998), "XVII: Nova Scotia", The Flags of Canada, University Park, retrieved 10 July 2009

- Department of Canadian Heritage, Ceremonial and Canadian Symbols Promotion > The Canadian Monarchy > 2005 Royal Visit > The Royal Presence in Canada - A Historical Overview, Queen's Printer for Canada, archived from the original on 7 August 2007, retrieved 4 November 2007

- Royal Visits to Canada, CBC, retrieved 10 July 2009