Monte Carlo Rally

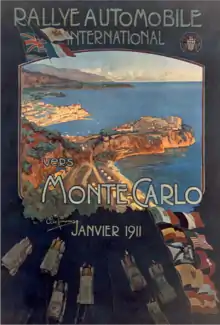

The Monte Carlo Rally or Rallye Monte-Carlo (officially Rallye Automobile de Monte-Carlo) is a rallying event organised each year by the Automobile Club de Monaco. The rally now takes place along the French Riviera in Monaco and southeast France. Previously, competitors would set off from various starting points around Europe and 'rally' (in other words, meet) in Monaco to celebrate the end of a unique event. From its inception in 1911 by Prince Albert I, the rally was intended to demonstrate improvements and innovations to automobiles, and promote Monaco as a tourist resort on the Mediterranean shore.

| Monte Carlo Rally | |

|---|---|

1911–2011 Centenary logo | |

| Status | Active |

| Genre | Motorsporting event |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Location(s) | Europe, France, Africa and Monaco |

| Inaugurated | 1911 |

History

1911-1912 elegance, controversy and adventure

In 1909 the Automobile Club de Monaco (Sport Automobile Velocipédique Monégasque) started planning a car rally at the behest of Albert I, Prince of Monaco. The Monte Carlo Rally was to start at points all over Europe and converge on Monte Carlo. In January 1911 23 cars set out from 11 different locations. Except for some glazed frost on the road, most of the itineraries were not too bad for January. However, the two participants starting from Vienna (1319KM) did not reach their destination because of temperatures of -18 Celsius and 40cm of iced snow on the roads. The event was won by Henri Rougier in a Turcat-Méry 25 Hp, who was one of nine drivers who left Paris to cover a 1,020 kilometres (634 mi) route. The rally comprised both driving and then somewhat arbitrary judging based on the elegance of the car, passenger comfort and the condition in which it arrived in the principality. The outcry of scandal when the results were published changed nothing, so Rougier was proclaimed the first winner.[1][2]

.jpg.webp)

In 1912 the Rallye Automobile de Monte-Carlo attracted 60 actual starters. There were now ten different starting points from where to rally towards the Principality of Monaco (Actually: ‘Rallye Automobile Monaco’ was on their cars plates). With an average required speed of 25 km/h (16 mph) this meant that the character was mostly touring, and the participants mostly used comfortable closed limousines. As these participants were often affluent owners, it was not uncommon that most of the driving was done by their chauffeurs. The most adventurous new starting city was Saint Petersburg in the Russian Empire, 3.257 km (2.024 mi) of winter roads away from Monte Carlo. It took more than 8 days for the only courageous participants - Andrej Platonovitsj Nagel and Vagyim Alekszandrovics Mihajlov in a Riga-built Russobalt S24-55 - to cover that distance. The low average of 16.7 km/h (10.4 mph) (and reputedly the less-than-shiny appearance of the car upon arrival and inspection by the judges) dropped them back to ninth place.

The winner, with an average of 29.2 km/h (18.1 mph) all the way from Berlin, just like the year before - was Julius Beutler from Germany. This time not in a Swiss built Martini, but in a French built Berliet. Second place was for his compatriot Karl Friederich von Esmarch, who had finished high the year before but was disqualified after protesting. Apparently in 1912 the arbitrary judging regarding style and presentation resulted in bad publicity. This caused the withdrawal of financial backing from the Societé des Bains de Mer for 1913 and 1914. Organizer Antony Noghès used another few years after the end of the Great War to rethink the formula of the event with promotion of the Principality keenly in mind.

1924-1939 organizers' challenge to find the right drivers' challenge

The period between 1924 and 1939 can be characterized as a difficult and sometimes frustrating search for an event to truly and fairly challenge the competitors and their vehicles. This was particularly hard because of the rapid development of not only the motor cars in that period, but also of the quality of the roads and their maintenance in winter.

Firstly, changing the date from January to March in 1924 was unsuccessful, even though reverting to January after that often lacked really snowy and icy circumstances for all participants. They would meet these circumstances depending on the weather on the way from their starting points. For several years for example, starting from Athens meant that heavy snowfall on Balkan roads frequently prevented participants from reaching Monte Carlo. Not because they were going to slow, simply because the roads were all blocked.

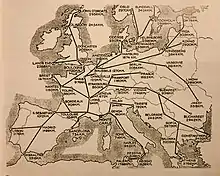

Secondly, the brilliant idea of rallying from all corners of Europe (and in 1925, Tunis in North Africa) inspired the right kind of adventure that well-off men and women in these days had in mind. Obviously, the longer the distance the higher the reward in points. Especially as in the outer corners of Europe the quality of the roads was questionable, reaching the starting point before the rally actually began was sometimes more challenging than rallying. Where in 1924 Glasgow was far far away, in 1926 John o'Groats in the far North of Scotland was a new challenge. Likewise, Königsberg was a challenge, but Tallinn in Estonia even more. Other starting points were Jassy in Rumania, Constantinople, Umeå in Northern Sweden, or Palermo in Sicily. The calculation method for distance covered however put almost always any participant not starting from the farthest point was beforehand down as a non-winner, before the event even started. Only from 1934 would this imbalance be addressed.

Thirdly, cars were improving enormously. Even in cold winter weather and over distances of up to around 3,750 km (2,330 mi) they rapidly became reliable. What before the Great War only seemed possible in large, closed saloons or possibly fast sports cars proved to be possible for what one could call "humble" (and far more affordable) closed four-seater like the Fiat 509 in 1928, with a 990 cc four-cylinder engine. Other smaller cars included the Amilcar in 1927 and the La Licorne in 1930. Therefore, the organizers from year to year increased the minimum average speed required on the open road from the starting points to Monte Carlo. This minimum doubled from 30 km/h (19 mph) in 1924 to 60 km/h (37 mph) from 1936 onwards, and the percentage of starters that reached the Mediterranean did not decrease. Organizers were forced to respond to this engineering progress from the manufacturers.

Fourthly, just a contest of distance and regularity no longer was enough to draw attention from participants, press and the public at large. Upon arrival many participants had scored the same amount of points, or did not get any penalties. They all had withstood the challenging rally with the same result. Obviously, some sort of final test or tests - preferably in or in the vicinity of Monte Carlo for attracting tourists - would have to be devised. These final tests were different almost every year, sometimes the changes were successful, sometimes they were not. These special "epreuves" were published in advance and often very detailed. Automobile clubs (like the RAC in Great Britain and the KNAC in the Netherlands) even organized simulation events on testing grounds for the diligent and well prepared participants. For several years this test was a 83 km (52 mi) regularity stage over some mountain passes like the Col de Braus. In 1929 and 1930 this stage was even a double lap of 160 km (99 mi). In some years there was also a short hill climb. From 1931 to 1937 the main test was - every year a little different - an acceleration, braking, reversing and steering contest on the Boulevard Albert 1er, Monaco. One year there was even a slow driving (in high gear) contest! This required a combination of driver skills and car capacities. Unfortunately, smart participants adapted their vehicles legally (there were no rules regarding the specification of the cars) with race car engines (Delahaye), left/right wheel brakes (Ford), light weight bodies (Triumph), special clutches (Invicta) or lower gearing (Hotchkiss). Form 1938 onwards these were forbidden. Standard (saloon) cars were mandatory, and there had to be a production of at least 30 identical vehicles, so no more specials! That year also saw the introduction of a real challenging route from Grenoble along the Route Napoleon to Monte Carlo, where snow and ice were much more likely to be encountered, over more than 350 km (220 mi). This was divided in several sub-sections where the required ‘regularity’ speed required real rallying in the modern sense of the word...

Despite all these challenges, the Monte Carlo Rally had become the most famous Rally in the world, attracting equally famous participants (drivers and co-equipiers), including racing drivers like Caracciola, Wimille, Chiron and Sammy Davis. (The last one was often winner of the separate Concours Prize for the most lavishly presented car (inside and outside). More remarkable was the competitiveness of female drivers ("lady drivers" in those days). In 1924 a "Madame Repusseau" accompanying her husband, already a year later a "Madame Mertens" (so far no first name found..) accompanied by her husband, all the way from Tunis in an open Lancia Lambda won second place. "Madame Marika" (so far no last name found...), Mildred Bruce, Lucy O’Reilly Schell, Kitty Brunell, Charlotte Versigny, Germaine Rouault, Mme Y. Simon not only performed well in the "Coupe de Dames" (since 1927, for all-female teams) but some of them were top three finishers overall.

1949-1956 from amateur drivers to works teams

It took some time after the Second World War for the organizers - still with Anthony Noghès in charge - to put a new Rally together. Europe changed geographically and politically. New countries, new borders, so Prague was the only possible starting point behind the Iron Curtain. Instead of the rallying to meet near Monte Carlo, now there was a circular route from Monte Carlo to Amsterdam and back. However, during these years the quality of cars and roads in Europe shifted the real challenge from that first part to the second part of the event. A "Circuit Montagne" developed during these years that became more and more difficult. In 1956 it even included the famous Col de Turini. Still, these were regularity runs during which the best time keeping equipe would most likely win. Sometimes (like in 1953) the difference between the winner and the runner-up would be just one second - one second difference in penalty on the regularity contest that is. Also, this Mountain Circuit with higher altitudes meant a bigger chance on real winter weather with snow(fall) and ice.

During these years, works or works supported teams became more and more important. From 1949 onwards, there was a special Team prize. First winners were the three Allards of Potter, Godsall and Imhof. Simca, Delahaye, Sunbeam-Talbot, Jaguar were subsequent winners. Obviously, Sydney Allard - as the first and only winner driving his own car - was driving a "works" car in 1952, but Gatsonides also participated in a factory prepared Ford Zephyr in 1953, a year that saw no fewer than eight factory backed Sunbeam-Talbots.[3] In 1956, the winning Jaguars were previously entered by the Jaguar company as saloon car racers. In fact, the Norwegian participants Malling and Fadum were the last real privateer winners in 1955 with their Sunbeam.

Also, there was a move to much more professional preparation. Where in the 1930s participants practised the intricacies of the acceleration, braking and steering contest in advance, in the 1950s participants practised the regularity stages. The most dedicated probably was Maurice ("Maus") Gatsonides who allegedly drove the Circuit Montagne 32 times before the start of the event.

1958-1961 front-wheel drive, rear-wheel drive, front engine, rear engine, anything goes

Skipping 1957 because of the Suez crisis - with fuel rationing and a ban on motor sports events for several months - the next few years witnessed very different winners. Cars with completely different technical lay-outs were capable of winning. Especially when there was snow, the right combination of power and traction made all the difference. Because tyre technology was still in its infancy, more power was not really essential. In 1958 a rear-engined, rear-wheel-drive car would be successful, with only 36 CV (26 kW) but with the weight of the engine over the driving wheels. A year later, the completely reversed lay-out of a Citroën ID (a simple version of the DS) was dominant with front-engine and FWD. In 1960 the classical lay-out of the Mercedes-benz 220SE (front-engined, rear-wheel-drive) proved to be the winning formula. In 1961 - with the help of regulations that favoured large but small engined cars - the Panhard Tigre (PL17) was another example of a light weight combination of front-engined FWD. 1961 was also the year that saw the introduction of no less than five Regularity contests over the mountain roads turned into Special Stages were only speed counted. Probably inspired by Scandinavian rallies, this also signalled the rise to fame of Scandinavian rally drivers in the Monte.

1962-1973 the rise of Scandinavian driver skills and of more specialized rally cars

With the improvement of tyre technology, the advantage of front-engined FWD cars slowly shrunk. But limited horsepower did not prevent Saab (96, with Erik Carlsson) in 1962/1963 and BMC Mini (Cooper S, with more Scandinavian and British drivers) in 1964/1965/1967 from winning the often snow-packed Monte's with more and more of these exciting Special Stages. (Even the 1966 winner-after-disqualification-of-3 BMC-Mini's was a Citroën DS FWD with just 109BHP).

After that, better (studded) tyres made it possible to use the full power of sportscars like Porsche (911, with Elford and Waldegård) in 1968/1969/1970 in the all deciding Special Stages. Rear-engined and rear-wheel drive, just like the slightly less powerful but definitely more lightweight Alpine-Renault (1600 S with Andersson and Andruet) in 1971/1973. 1972 winner was the Lancia Fulvia, a sportscar with a front-engined FWD layout. Driver was Sandro Munari, who would dominate the next era of dedicated rally supercars.

This periode also saw full involvement of the tyre companies, including a wide selection of available tyres for all types of weather, spotters for teams to assess the actual circumstances on the mountain roads and the all important right tyre choice. The difference between winning and losing was in some years just 6 seconds after more than 4,000 km (2,500 mi) of rallying.

1975-1980 The hayday of special stages and rally supercars

.jpg.webp)

After another petrol crisis (following the Yom Kippur war) as a result of the stop of crude oil exports to Europe the 1974 edition was cancelled. By 1975 the participants had nearly cracked all nuts in Monte efficieny. On the human side professional works teams with professional drivers and advisors (funded now by ‘’extra sportive’’ or commercial sponsors), on the technical side engine technology that brought horsepower to the wheels and tyres on those wheels that could cope with all road circumstances imaginable. The final step was a car that would be specifically designed for rallying, and produced at least 400 times (as required for the Group 4 regulations allowed in the sport from 1971). Design with respect of course to engine position and what (two!) wheels to drive, but also regarding weight, chassis stiffness, suspension-and-damper characteristics, brakes and agility in steering. The Lancia company did just that, all of that when developing the Lancia Stratos HF. Purpose-built, and the looks to show exactly that. With Sandro Munari they were unbeatable from 1975 to 1977 with the 24 valve Ferrari V6 engine. In 1978 (with a 12 valve engine from that year on) they had a definite off-year with just Michèle Mouton surviving to the end. In 1979 they won again with Bernard Darniche in a semi works Stratos and in 1980 Darniche was second, behind what could be seen as an internal (corporate FIAT empire) competitor: the Fiat 131 Abarth of Walter Röhrl...

1981-1986 Four-wheel drive and Group B rally cars

These years the first four-wheel-drive cars appeared. Allowed form 1979, in fact the Audi Quattro was the first to be entered in 1981, but it took some years to become successful. Combined with the arrival of Group B regulations from 1982 (200 cars to be built with vast freedom in design and almost unlimited power with turbo engines developed and allowed) this made rally cars incredibly fast. And incredibly hard to drive. No clear and dominant car in this period, but more a dominant driver and co-pilot. Walter Röhrl and Christian Geistdorfer proved they could drive very different cars to victory. After their success with the front-engined-rear-drive Fiat in 1981 they repeated this with an Opel Ascona 400 (same lay-out) in 1982. Subsequently, in 1983 they were victorious with a Group B Lancia 037 Rally (mid-engine-rear-drive) and in 1984 with an Audi Quattro (front-engine-four-wheel-drive). In 1981 Jean Ragnotti was successful with the mid-engine-rear-drive Renault 5 turbo, which was a very different car compared to the podium finishing Renault 5 Alpines of 1978. The fact that the Renault 5 Turbo was built in the Dieppe factory of Alpine explains a lot. Renault built nearly 5.000 of them, so this was at least a car ordinary people could buy. In 1985 and 1986 Peugeot and Lancia were successful with extremely powerful, fully developed Group B mid-engine-four-wheel-drive turbo-engined cars. Henri Toivonen (the son of 1966 winner Pauli Toivonen) died in a crash later that year during the Tour De Corse. The regulatory body FIA immediately banned Group B from rallying. However, Lancia was able to develop their Delta into a Group A version and maintain their success in the next era...

1987-1996 Group A & Group N rally cars

During these ten years the Martini sponsored Lancia team was the best to develop a competitive car to Group A specifications after the ban on Group B (mostly silhouette racing cars with just an outward similarity to normal production cars). Based on the normal Lancia Delta, the team developed the HF, the Integrale and Integrale 16V to stay competitive, with a total of five wins of which to by Italian Miki Biasion. From 1990 onwards, real competition came from [[Toyota Team Europe]] - led by 1971 winner Ove Andersson - with Carlos Sainz as their main driver in a Celica. At the end of the period the Ford Escort RS Cosworth (like the Lancia and the Toyota a homologation special of which 5000 cars had to be built) claimed victory in the hands of Francois Delecour. The typical Group A car had a four-wheeldrive front engined 2.0 litre 16 valve turbocharged layout. Sainz - Toyota and Subaru - and Didier Auriol - Lancia and Toyota - showed their skill with victories for different constructors, with Sainz driving a Subaru Impreza 555 to underline the ascent of the Japanese rallying teams. The concentration runs became more and more obsolete and the main event consisted of 20-25 special stages totalling about 500-600 km. The closest finish was in 1993, with just 15 seconds (after 594 km) separating Auriol's Toyota Celica and Delecour's Ford Escort. The rally was the first event on the WRC calendar, except for 1996 when it did not count for the WRC Championship.

1997-present WRC regulations and the reign of Mäkinen, Loeb and Ogier

One of the most remarkable facts over the last twentysome years is that just three drivers won 18 out of the 24 events. Tommi Mäkinen four times in a row and later Sébastien Loeb and Sébastien Ogier seven times each! Proof of their unique skills is that they drove at least two different cars. Mäakinen retired in 2003, at the age of 39, Loeb retired in 2014 at the age of 39 and Ogier is still active (born in 1983). Mitsubishi (2), Citroën (8), Peugeot (2, in the 2009-2011 IRC regulations era), Ford (4) and Volkswagen (3) were the most successful constructors in this period, with Hyundai from South-Korea in 2020 a new kid on the block.

Also a quite radical break with the past is the concentration of the Special Stages around one location, where cars can be serviced. In stead of a series of stages in line, with in between sections to go the next stage it changed from 1997 to a kind of flower with a return to the petal after each special stage. Also the rays of the star (the concentration from all over Europe to Monte Carlo) disappeared. The main reason for these changes was safety. Safety especially for the spectators who were still turning out in huge numbers to watch the spectacle of the special stages. On YouTube there are several Monte Carlo Rally videos that make very clear that crowd control is nearly impossible and accidents can easily turn into drama. Also, the more concentrated layout minimizes the traffic by spectators.

(Under construction, the regulations, the cars, etc.)

The event as part of FIA Championships: ERC, WRC and IRC

From its introduction in 1953 to 1972 the Rallye was part of the European Rally Championship, except in 1968 and 1969. From 1973 to 2008 the rally was held in January as the first event of the FIA World Rally Championship, but between 2009 to 2011 it has been the opening round of the Intercontinental Rally Challenge (IRC) programme, a championship for N/A 4WD cars, before returning to the WRC championship season again in 2012. As recently as 1991, competitors were able to choose their starting points from approximately five venues roughly equidistant from Monte Carlo (one of Monaco's administrative areas) itself.

With often varying conditions at each starting point (typically comprising dry tarmac, wet tarmac, snow, and ice, sometimes all in a single stage of the rally), this event places a big emphasis on tyre choices, as a driver has to balance the need for grip on ice and snow with the need for grip on dry tarmac. For the driver, this is often a difficult choice as the tyres that work well on snow and ice normally perform badly on dry tarmac.

The Automobile Club de Monaco confirmed on 19 July 2010 that the 79th Monte-Carlo Rally would form the opening round of the new Intercontinental Rally Challenge season.[4] To mark the centenary event, the Automobile Club de Monaco has also confirmed that Glasgow, Barcelona, Warsaw and Marrakesh have been selected as start points for the rally.

Remarkable facts about the event

Firsts and lasts during Rallye Monte Carlo history

During the more than 100 years of history there have been many remarkable firsts in the event. Also - because of the continuous change in the way the Rallye Monte Carlo was run - there have been as many lasts. This is a summary of firsts and lasts.

1911 First: an event to ‘’rally’’ to Monte Carlo (Monaco) from six different starting points (Geneva representing the minimum distance of 670KM)

1912 Last: Points for the main event to be won for elegance and appearance of the car (0-10 points for 4 different aspects)

1924 First: a hillclimbing speed test (at Mont Agel)

1924 First and last: event held in March

1924 First: a regularity stage over a mountainous road circuit (over the Col de Braus)

1927 First: a special trophy for all-female teams, the Coupe des Dames (already in 1925 lady drivers finished on the podium)

1931 First: an acceleration and braking test (this was held on the seafront, as the final part of the event)

1932 First and last: a slow driving test in high gear over 100m (the winner managed it in 2m35s)

1937 Last: The possibility to participate with a Bus or Coach or a car with caravan (thus gaining extra points for extra travellers)

1938 First: No special bodied or modified cars were allowed anymore. Only saloons or drophead coupes of which 30 identical examples had been built

1951 First: a speed and regularity test on the full Monaco Grand Prix circuit (4 laps as fast but also each lap as regular as the other)

1953 First: for the first time the Rally was part of a bigger championship; the new European Rally Championship

1961 First: a Special Stage, a timed section (on mountain roads) where not a regular speed or a minimum speed was required but the highest speed possible. Until 1968 the times set by a car for each Special Stage were recalculated according to a handicap or index that was different each year. This was usually according to FIA Group 1, 2 or 3 homologated cars.

1973 First: a female partipant takes the overall victory. (This was Michèle Espinosi-Petit - nicknamed ‘’biche’’ - partnering Jean-Claude Andruet in the Alpine-Renault)

1973 First: the Rally was part of the new World Rally Championship. (It was in fact the very first event on that calendar)

1981 First: a four-wheel-drive car participated in the Rally (also: was allowed to participate; it was the Audi Quattro)

1997 Last: the original Concentration Run from all-over Europe to ‘’rally’’ to Monte Carlo on common and open roads - often over more than 3000KM. (In 1997 this was only possible for non-works participants)

Sabotage, disqualifications and outrage: the hottest disputes in a cold winter rally

(Under construction)

1954 controversy The winner of the event was Louis Chiron, famous Grand Prix driver (between 1931 and 1955), and the first Monegasque driver to win the Monte. The question was whether his Lancia Aurelia B20 with 2500cc engine was a normal production car. Competitors believed it was an older chassis fitted with the new 2500cc engine. A combination that had never been in production. Claims were brought to the green table: the FIA decided many weeks after the event that the claims were not true....

1966 controversy The 1966 event was the most controversial in the history of the Rally. The first four finishers, driving three Mini-Coopers, Timo Mäkinen, Rauno Aaltonen and Paddy Hopkirk, and Roger Clark's 4th-placed Ford Cortina were all disqualified because they used non-dipping single filament quartz iodine bulbs in their headlamps, in place of the standard double filament dipping glass bulbs, which are fitted to the series production version of each models sold to the public.[5] This elevated Pauli Toivonen (Citroën ID) into first place overall. Rosemary Smith (Hillman Imp) was also disqualified from sixth place, after winning the Coupe des Dames, the ladies' class. In all, ten cars were disqualified.[6] Teams threatened to boycott the event.[7] The headline in Motor Sport read "The Monte Carlo Fiasco."[8]

Remarkable participants with a long list of appearances in the event

Some participants were regular fixtures and would come back every January to the magic of the most famous rally in the world. Often in very different cars and from very different starting points. Sometimes not very successful but some with a record of more than 30 entries. As a driver or as a navigator. This is a selection of them.[9]

- Leif Vold-Johansen (1912-1996)

This Norwegian driver participated in no less than 38 editions of the RMC. His final outing was when he was 80, in a Volkswagen Golf GTi 16v, and he achieved his best result with a third place in 1960 with a DKW.

- Marc Dessi (1956)

This Monegasque driver partipated in 40 editions of the RMC, starting in 1976 in a Fiat 124 with his wife Carla as co-pilot and rallying from 1998 together with his daughters Vanessa or Pamela, in cars such as a Renault Twingo. His 2019 car had ‘’Daghe Munegu’’ in his local language on the roof. It means: ‘’Go, Monaco!’’

- Jens Nielsen (1918-2018)

This Danish driver first participated in 1961 (in a Volkswagen) at the age of 42 and started 28 times until his final appearance in 1992 at the age of 73 in a Renault Clio. His best result was in 1965, in a Volvo PV 544.

- Bruno Saby (1949)

This French driver won the 1988 Rally Monte Carlo in a Lancia. His first appearance was in 1971, driving a Ford Capri. After his last full season as a professional driver in 1991 he reappeared in the Monte from 2015 onwards, almost 70 years old in his most recent (and 22nd) drive in a Renault Megane RS.

- Greta Molander (1908-2002)

This Norwegian driver competed before and after World War 2. Overall 18 editions, before the war usually in Chryslers, after the war in FWD's. She won the Coupe des Dames in 1937 and 1952. Her first entry was in 1933.

- Maurice Gatsonides (1911-1998)

This Dutch driver participated 14 times, between 1936 and 1965, winning in 1953. He was known for his meticulous preparation and drove very different cars from the very big Humber Super Snipe to small cars like a Hillman Imp. His first appearance was driving a Hillman, his last with a Sunbeam Tiger. He also built his own cars in which he rallied: the Gatford and the Gatso. He used his experience with driving very precise average speeds in rallys (with good timekeeping) later to develop the Gatsometer, a device used by the police to monitor illegal speeding.

- Pat Moss-Carlsson (1934-2008)

Younger sister to Grand Prix driver Stirling Moss and one of the most successful female rally drivers of all time. Patricia married two time Monte winner Erik Carlsson in 1963 and drove her first Monte in 1958 (with Ann Wisdom-Riley, in an Austin A40) and her last one in 1973 (with Elisabeth Crellin, in a Renault A110). She holds the record of 8 Coupe des Dames wins in the Rally Monte Carlo.

.jpg.webp)

Remarkable cars that took part in the event

In over a century of history, until the arrival of specialized rallycars and homologation specials that were not really for sale for common motorists, nearly every car could be used to compete in the Monte Carlo Rally. And nearly every car was used. Small cars like the Fiat 509 in 1928 or the Licorne 5CV in 1930. Large cars like the Graham-Paige in 1930 or the Mercedes-Benz 220SE in 1960. Even huge cars like the Renault 40CV in 1925 (although that car really required extra reverse gear manoeuvering on the Col de Braus!). Anything goes, anything went and any car could be successful.

Especially before 1938 - when there were no specific rules or regulations regarding to the car you drove - there were some really remarkable entries. This is a short selection.

- 1912 Delaunay-Belleville with double rear tyres

- 1929/1930 Weiß Manfred prototype

- 1935 Bentley with Gardner Diesel engine prototype driven by Lord de Clifford

- 1931 Kegresse half-track car

- 1936 Ford V8 ‘speciale’ with many modifications driven by Cristea and Zamfirescu

- 1932 Hillman car with Eccles caravan entered by Dudley Noble

- 1934 Citroën Autobus

- 1936 Commandant Berlescu’s special halftrack Ford V8 based vehicle with quick- detachable front ski's and double rear-axle

Remarkable roads and routes that were used in the event

The longest road

- In 1912 the road from Saint Petersburg was really the most challenging with lots of snow. Although it took a long time the single crew that started from there actually arrived in Monte Carlo and finished in 9th place.

- In 1925 Tunis was an incredible 4.760 km away from Monte Carlo. Not really a winter challenge for the African part, but in the Twenties it must have been a real challenge in itself.

- Before 1934 Athens was a tempting challenge as starting place because the distance gave those who arrived without penalties in Monte Carlo the most points. But from Athens, sometimes even before reaching Saloniki, the winter roads would be blocked by snow and impossible to use. Until 1934 no participant from Athens would succeed in reaching Monte Carlo....

- In 1971 Agadir in Morocco was perhaps the most exotic starting place ever in the Monte Carlo Rally.

The Grand Prix de Monaco circuit

The most special of Special Stages? Col de Turini

Since 1961, this rally features one of the most famous special stages in the world. The stage is run from La Bollène-Vésubie to Sospel, or the other way around, over a steep and tight mountain road with many hairpin turns. On this 31 km (19 mi) route it passes over the Col de Turini, a mountain pass road which normally has ice and/or snow on sections of it at that time of the year. Spectators also throw snow on the road—in 2005, Marcus Grönholm and Petter Solberg both ripped a wheel off their cars when they skidded on snow probably placed there by spectators, and crashed into a wall. Grönholm went on to finish fifth, but Solberg was forced to retire as the damage to his car was extensive. In the same event, Sébastien Loeb set one of the fastest times in the modern era, with 21 minutes 40 seconds.

Sospel has an elevation of 479m, and the D70 has a maximum elevation of 1603m, for an average gradient of 6.7%. The Turini is also driven at night, with thousands of fans watching the "Night of Turini", also known as the "Night of the Long Knives" due to the strong high beam lights cutting through the night.[10][11] In the 2007 edition of the rally, the Turini was not used, but it returned for the 2008 route.[12] For both the 2009 and 2010 event the stage was run at night and shown live on Eurosport.

Past winners of the event, including second and third places

1911–1972

| Year & Edition | Winner | Second | Third | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrant/Nationality | Car & Type (engine displacement) | Starting #/ License plate | Place of departure (Km) | Entrant/Nationality | Car & Type (engine displacement) | Starting #/ License plate | Place of departure (Km) | Entrant/Nationality | Car & Type (engine displacement) | Starting #/ License plate | Place of departure (Km) | |

| 1911 I | Henri Rougier (F) | Turcat-Méry 25HP Double coupé | #1 793 WI |

Paris (1020 km) | J.A. de Aspiazu (6 travellers) | Gobron-Brillié 40CV torpedo cabriolet (7600cc) | #3 ...6-E |

Paris (1020 km) | Julius Beutler (D) | Martini 28/35 HP landaulet | #13? |

Berlin (1700 km) |

| 1912 II | Julius Beutler (D) | Berliet 16CV | #69 IA-5135 |

Berlin (1700 km) | (Captain) Karl Friedrich Von Esmarch (D) | Dürkopp 12/64 HP | #26 IA-6028 |

Berlin (1700 km) | Paul Meunier (F) (7 travellers) | Delaunay-Belleville 40 CV Conduite Interieure (double rear tyres) | #9 | Le Havre[13] (1229 km) |

| 1913–23 | ||||||||||||

| 1924 III | Jacques Edouard Ledure & Madame Ledure (B) (4 travellers) | Bignan 11CV conduite interieure (1975 cc) | #62 | Glasgow (2006 km) | M.G. Marquet Fils | Métallurgique 2 litres, conduite interieure Vanden Plas (1970 cc) | #64 | Amsterdam (1527 km) | Barbillon | Bignan 11CV conduite interieure (1975 cc) | #77 | Boulogne-sur-Mer (1269 km) |

| 1925 IV | François Repusseau & Madame Repusseau (F) (6 travellers) | Renault 40CV Conduite Interieure (9131 cc) | #4 | Tunis (3860 km) | Madame Mertens (& Monsieur Mertens) (2 travellers) | Lancia Lambda (2400 cc) | #42 5829 G8 |

Tunis (3860 km) | Lt. Lamarche | FN (1460 cc) | #21 | Tunis (3860 km) |

| 1926 V | Victor A. Bruce / William J Brunell (GB) (2 travellers) | Autocarrier AC Six twoseater drophead coupé (1991 cc) | #12 PE 7799 |

John O’Groats (2461 km) | Pierre Bussienne (F) | Sizaire Frères (1993 cc) | #35 | Brest | Madame "Marika" [14] | Citroën B2/B10 (1452 cc) | #36 | Brest |

| 1927 VI | Marcel Lefebvre-Despeaux (F) (5 travellers) | Amilcar CGSS Sedan (cozette)[15] (1089 cc) | #29 9053 X3 |

Königsberg (2643 km) | Pierre Clause (F) | Celtic-Bignan (1100 cc) | #19 | Königsberg (2643 km) | Pierre Bussienne (F) | Sizaire-Frères (1993 cc) | #32 | Königsberg (2643 km) |

| 1928 VII | Jacques Bignan (F) (5 travellers) | Fiat 509 Sedan (990 cc) | #24 2212 X3 |

Bucharest | E. P. Malaret (5 travellers) | Fiat 509 (990 cc) | #1 60??? |

Königsberg | Charlotte Versigny (F) | Talbot 70 sedan (1672 cc) | #2 | Bucharest |

| 1929 VIII | Jacques Johan Sprenger van Eijk (NL) / Frits Rodrigo (NL) / Loten van Doelen Grothe[16] (NL) / van Soeren (NL)(4 travellers) | Graham-Paige 619 (4718 cc) | #43 P-4910 |

Stockholm (2961 km) | Viktor Szmick (HU) / Emánuel Csajkovszky / Laszlo Wolfner ? / Ferenc Pesti ? | Weiss Manfréd prototype (875 cc) | #41 8 27 193 |

Bucharest | IJsbrand Visser (NL) | Lancia Lambda (2400 cc) | #57 | |

| 1930 IX | Hector Petit (F) / Robert Lestienne (F) / André Galloisy (F) (3 travellers) | Licorne 5CV torpedo 2 portes (905 cc) | #27 | Jassy (3518 km) | (Commandant) Alex C. Berlesco (or: Berlescu) (RO) | DeSoto Model K Roadster six (2799 cc) | #86 UW 3148 (?) |

Jassy (3518 km) | Abel Blin D'Orimont (B) | Studebaker (5380 cc) | #25 | Jassy (3518 km) |

| 1931 X | Large cars: Donald Healey (GB) / Lewis Pearce / Humfrey E. Symons (GB) (3 travellers) | Invicta S-type 4.5 Litre (4467 cc) | #128 PL 3188 |

Stavanger (3638 km) | Jean-Pierre Wimille (F) | Lorraine coupe sport B3-6 (3500 cc) | #121 | Stavanger (3638 km) | Madame Lucy Schell (USA) | Bugatti T44 Berline Gangloff (2991 cc) | #167 2059 RE4 |

Stavanger (3638 km) |

| Small cars (<1100cc) Victor E. Leverett (GB) | Riley Nine Monaco Saloon (1087 cc) | #4 GN7 |

Stavanger (3638 km) | de Lavalette | Peugeot | Madame ‘’Jeanne’’ | Rosengart | |||||

| 1932 XI | Large cars: Maurice Vasselle (F) / François Duhamel (F) | Hotchkiss AM 2 (2475 cc) | #64 9558 RF4 | Umeå (3750 km) | Donald Healey (GB) | Invicta S-type 4.5 litre low chassis (4467 cc) | #1 PL 9662 |

Umeå (3750 km) | Boris Ivanowski (RU)/ Mary Ham | Ford V8 (3284 cc) | #62 | Umeå (3750 km) |

| Small cars (<1500 cc): G. de Lavelette (F)/Charles de Cortanze (F) | Peugeot 201C (1085 cc) | #212 3084 RF4 |

Umeå (3750 km) | André Boillot (F) | Peugeot 201C (1085 cc) | #211 3085 RF4 |

Athens (3785 km) | Victor E. Leverett (GB) / George Dennison (GB) | Riley Six Alpine Tourer (1486 cc)[17] | #208 VC 9899 |

Umeå (3750 km) | |

| 1933 XII | Maurice Vasselle (F) / Buzi (F) / Maret (F) | Hotchkiss AM80 S (3485 cc) | #1 8291-RG1 |

Tallinn (3780 km) | Robert Guyot (F) | Renault Nervasport (4241 cc) | #34 4259 RC |

Tallinn (3780 km) | Madame Germaine Rouault (F) / Julio Quinlin (F) | Salmson S4C (1495 cc) | #15 5856 RG |

Tallinn (3780 km) |

| 1934 XIII | Louis Gas (F) / Jean Trévoux (F) | Hotchkiss AM80 S (3485 cc) | #4 9683 RT |

Athens (3786 km) | Marc Chauvierre-Lanciano (F) (4 travellers) | Chenard-Walcker Aigle V8 (3600 cc) | #17 5630 R?? |

Athens (3786 km) | Donald Healey (GB) / Lewis Pearce (GB) (3 travellers ?) | Triumph Gloria "special" (1232 cc) | #151 KV 6905 |

Athens (3786 km) |

| 1935 XIV | Charles Lahaye (F) / René Quatresous (F) | Renault Nervasport CS (4827 cc?) | #51 8000 UD 2 |

Stavanger (3696 km) | Jack C. Ridley (GB) | Triumph Gloria "special" (1232 cc) | #23 KVG 90? |

Umeå (3780 km) | Madame Lucy O'Reilly Schell (USA) / Laury Schell(USA) | Delahaye 135 (3557 cc) | #136 1821-RJI |

Stavanger (3696 km) |

| 1936 XV | Petre G. Cristea (RO)/ Ionel Zamfirescu (RO) | Ford Model 48 two-seater convertible "speciale" (3622 cc) | #16 1701-B |

Athens | Lucy O'Reilly Schell (USA)| Laury Schell (USA) | Delahaye 135 Sport (3557 cc) | #41 707 RK |

Athens | Charles Lahaye (F) / [René Quatresous] (F) | Renault Vivasport (4085 cc) | #1 1330 DU 3 |

Athens |

| 1937 XVI | René Le Bègue (F) / Julio Quinlin (F) | Delahaye 135 MS Spéciale (3557 cc) | #20 1581 RK 2 |

Stavanger | Philippe de Massa (F) / Norbert-Jean Mahe (F) | Talbot (3988 cc) | #86 | Stavanger | [18] M. Jacobs / Tj. de Boer (NL) / Lindner [19] | Buick (4560 cc) | #103 | Stavanger |

| 1938 XVII | Gerard Bakker-Schut (NL) / Karel Ton (NL) / Klaas Barendrecht (NL) | Ford V8 two-door coupe (3622 cc) | #9 GZ 15572 |

Athens | Jean Trévoux (F) / Marcel Lesurque (F) | Hotchkiss 686 (3485 cc) | #12 3354 RL 4 |

Athens | Charles Lahaye (F) / René Quatresous (F) | Renault Primaquatre (2383 cc) | #93 8000 DU 3 |

Athens |

| 1939 XVIII | Jean Trévoux (F) / Marcel Lesurque (F), ex aequo Jean Paul (F) / Marcel Contet (F) |

Hotchkiss 686 GS Riviera cabriolet (3485 cc), ex aequo Delahaye 135 M (3557 cc) |

#7, ex aequo #31 |

Athens, ex aequo Athens (3812 km) |

Ernest Mutsaerts (NL)/ André Kouwenberg (NL)/ Paul Lamberts Hurrelbrinck (NL) | Ford V8 (3622 cc) | #71 | Palermo (4090 km) | ||||

| 1940–48 | ||||||||||||

| 1949 XIX | Jean Trévoux (F) / Marcel Lesurque (F) | Hotchkiss 686GS sedan (3485 cc) | #36 5940 RO 6 |

Lisbon | Maurice Worms / Edmond Mouche | Hotchkiss 686 GS sedan (3485 cc) | #38 | Monte Carlo | František Dobry (CZ) / Zdeněk Treybal (CZ) | Bristol 400 (1971 cc) | #68 P 28797 |

Monte Carlo |

| 1950 XX | Marcel Becquart (F) / Henri Secret (F) | Hotchkiss 686GS sedan ‘’Paris-Nice’’ (1939) (3485 cc) | #23 10 04 |

Lisbon | Maurice Gatsonides (NL) / Klaas Barendregt (NL) |

Humber Super Snipe (4086 cc) | #231 JHP 329 |

Monte Carlo | Julio Quinlin (F) /Jean Behra (F) | Simca 8 Coupé (1090 cc) | #224 821 RU8 | Monte Carlo |

| 1951 XXI | Jean Trévoux (F) / Roger Crovetto (F) | Delahaye 175 S Motto (4455 cc) | #277 3413 P 75 |

Lisbon | Comte/Conde? de Monte Real (P) / Manuel J. Palma (P) | Ford V8 (3622 cc?) | #332 HC-13-03 |

Lisbon | Cecil Vard (IRL)/ Bill A Young / Arthur Jolley (GB NI) | Jaguar Mark V (3485 cc?) | #211 ZE 7445 |

Glasgow |

| 1952 XXII | Sydney Allard (GB) / Guy Warburton (GB)/ Tom Lush (navigator) (GB) | Allard P1 (3622 cc Ford V8) | #146 MLX 381 |

Glasgow | Stirling Moss (GB)/ Desmond Scannell (GB)/ John Cooper (GB) |

Sunbeam-Talbot 90 (2267 cc) | #341 LHP 823 |

Dr. Marc Angelvin (F) / Nicole Angelvin (F) | Simca 8 Sport (1221 cc) | #293 5052 AE 13 |

||

| 1953 XXIII | Maurice Gatsonides (NL) / Peter Worledge (GB) | Ford Zephyr (2262 cc) | #365 VHK 194 |

Monte Carlo | Ian Appleyard (GB)/ Pat Appleyard (GB) | Jaguar Mark VII (3442 cc) | #228 PNW 7 |

Roger Marion / Jean Charmasson | Citroën 15 CV Six (2867 cc) | |||

| 1954 XXIV | Louis Chiron (MON) / Ciro Basadonna (I) | Lancia Aurelia B20 GT (2451 cc) | #69 142843 TO |

Monte Carlo | Pierre David / Paul Barbier (F) | Peugeot 203 (1290 cc) | #393 | André Blanchard / Marcel Lecoq (F) | Panhard Dyna X86 cabriolet (850 cc) | #394 | ||

| 1955 XXV | Per Malling (N) / Gunnar Fadum (N) | Sunbeam-Talbot 90 Mk III (2267 cc) | #201 A-68909 |

Oslo | Georges Gillard / Roger Duget | Panhard Dyna Z (848 cc) | #275 369 BX 63 |

Monte Carlo | Hanns Gerdum (D)/ Joachim Kühling (D) | Mercedes-Benz 220 (2195 cc) | #255 H94-8070 |

Munich |

| 1956 XXVI | Ronnie Adams / Frank Biggar (EI)/ Derek Johnston (GB/Northern Ireland) | Jaguar Mark VII (3442 cc) | #164 PWK 700 |

Glasgow | Walter Schock (D)/ K Raebe (D) | Mercedes-Benz 220 (2195 cc) | Michel Grosgogeat / Pierre Biagini | DKW | #331 845 DJ 06 |

|||

| 1957 | ||||||||||||

| 1958 XXVII | Guy Monraisse (F) / Jacques Feret (F) | Renault Dauphine Gordini R1091 (845 cc) | #65 9641 GN 75 |

Lisbon | Alexandre Gacon (F)/ Leo Borsa (F) | Alfa Romeo Giulietta (1290 cc) | #70 9646 AV 69 |

Leif Vold-Johansen (N) / Finn Huseby Kopperud (N) | DKW (896 cc) | #18 A 8052 |

||

| 1959 XVIII | Paul Coltelloni (F)/ Pierre Alexandre (F)/ Claude Desrosiers (F) | Citroën ID19 (1911 cc) | #176 3427 HP 75 |

Paris | André Thomas / Jean Delliere | Simca Aronde (1290 cc) | #211 28 DH 26 |

Pierre Surles / Jacques Piniers | Panhard 850 (848 cc) | |||

| 1960 XIX | Walter Schock (D)/ Rolf Moll (D) | Mercedes-Benz 220SE (2195 cc) | #128 S-JX 190 |

Warsaw | Eugen Böhringer (D)/ Hermann Socher (D) | Mercedes-Benz 220SE (2195 cc) | #121 S-JX 74 |

Eberhard Mahle (D)/ Roland Ott (D) | Mercedes-Benz 220SE (2195 cc) | #135 S-JX 71 |

||

| 1961 XXX | Maurice Martin (F) / Roger Bateau (F) | Panhard PL 17 Tigre (848 cc) | #174 9333 KJ 75 |

Walter Löffler (D)/ Hans-Joachim Walter (D) | Panhard PL 17 Tigre (848 cc) | #87 8758 TB 75 |

Guy Jouanneaux / Alain Coquillet | Panhard PL 17 Tigre (848 cc) | #220 957 FC 45 |

|||

| 1962 XXXI | Erik Carlsson (S)/ Gunnar Häggbom (S) | Saab 96 (841 cc) | #303 P 61444 |

Oslo | Eugen Böhringer (D) / Peter Lang (D) | Mercedes-Benz 220SE (2195 cc) | #257 S-JX 74 |

Paddy Hopkirk (GB NI)/ Jack Scott (GB) | Sunbeam Rapier (1592 cc) | #155 5192 RW |

||

| 1963 XXXII | Erik Carlsson (S)/ Gunnar Palm (S) | Saab 96 (841 cc) | #283 P 77558 |

Stockholm | Pauli Toivonen (FIN) / Anassi Järvi (FIN) | Citroën DS19 (1911 cc) | #233 7230 NC 75 |

Rauno Aaltonen (FIN) / Tony Ambrose (GB) | Mini Cooper (997 cc) | #288 977 ARX |

||

| 1964 XXXIII | Paddy Hopkirk (GB NI) / Henry Liddon (GB) | Morris Mini Cooper S (1071 cc) [20] | #37 33 EJB |

Minsk | Bo Ljungfeldt (S)/ Fergus Sager (S) | Ford Falcon Futura Sprint (4700 cc) | #49 ZE-1047 |

Erik Carlsson (S) / Gunnar Palm (S) | Saab 96 Sport (841 cc) | #131 P 44301 |

||

| 1965 XXXIV | Timo Mäkinen (FIN) / Paul Easter (GB) | Mini Cooper S (1071cc) | #52 AJB44B |

Stockholm | Eugen Böhringer (D) / Rolf Wütherich (D) | Porsche 904 (1966 cc) | #10 S-TJ 16 |

Pat Moss-Carlsson (GB) / Elisabeth Nyström (S) | Saab 96 Sport (841 cc) | #49 PA 12570 |

||

| 1966 XXXV | Pauli Toivonen (FIN) / Ensio Mikander (FIN) | Citroën DS21 (2175 cc) | #195 8625 SC 75 |

Oslo | René Trautmann (F)/ Jean-Pierre Hanrioud (F) | Lancia Flavia coupé (1800 cc) | #66 TO 759709 |

Ove Andersson (S) / Rolf Dahlgren (S) | Lancia Flavia coupé (1800 cc) | #140 TO 756708 |

||

| 1967 XXXVI | Rauno Aaltonen (FIN) / Henry Liddon (GB) | Mini Cooper S | #177 LBL 6D |

Monte Carlo | Ove Andersson (S) / John Davenport (GB) | Lancia Fulvia 1200 HF (1200cc) | Vic Elford (GB) / David Stone (GB) | Porsche 911S (1991 cc) | ||||

| 1968 XXXVII | Vic Elford (GB)/ David Stone (GB) | Porsche 911T (1991 cc) | #210 S-C9165 |

Warsaw | Pauli Toivonen (FIN) / Martti Tiukkanen (FIN) | Porsche 911S (1991 cc) | #116 4028 Z-97 |

Rauno Aaltonen (FIN) / Henry Liddon (GB) | Mini Cooper 1275S (1275 cc) | #18 ORX 7F |

||

| 1969 XXXVIII | Björn Waldegård / Lars Helmer (S) | Porsche 911S (1991 cc) | #37 S-L 2263 |

Warsaw | Gérard Larrousse (F) / Jean-Claude Perramond (F) | Porsche 911S (1991 cc) | #31 S-L 2264 |

Jean Vinatier / Jean-François Jacob | Alpine-Renault A110 1300S (1300cc) | #26 7753 GH 76 |

||

| 1970 XXXIX | Björn Waldegård (S) / Lars Helmér (S) | Porsche 911S (2195 cc) | #6 S-T 5704 |

Oslo | Gérard Larrousse (F) / Maurice Gélin (F) | Porsche 911S (2195 cc) | #2 S-T 5705 |

Jean-Pierre Nicolas (F) / Claude Roure (F) | Alpine-Renault A110 1300S (1300 cc) | #18 3413 GP 76 |

||

| 1971 XL | Ove Andersson (S) / David Stone (GB) | Alpine-Renault A110 1600S (1585 cc) | #28 8380 GU 76 |

Marrakech | Jean-Luc Thérier (F) / Marcel Callewaert (F) | Alpine-Renault A110 1600S (1600 cc) | #9 8385 GU 76 |

Marrakech | Björn Waldegård (S) / Hans Thorszelius (S), ex aequo Jean-Claude Andruet (F)/ G. Vial (F) |

Porsche 914/6 (1991 cc), ex aequo Alpine-Renault A110 1600S (1600 cc) |

#7 S-Y 7714, ex aequo .... |

Warsaw, ex aequo .... |

| 1972 XLI | Sandro Munari (I) / Mario Manucci (I) | Lancia Fulvia 1.6HF (1584 cc) | #14 E 24265 TO |

Almeria | Gérard Larrousse (F) / Jean-Claude Perramond (F) | Porsche 911S (2341 cc) | Rauno Aaltonen (FIN) / Jean Todt (F) | Datsun 240Z (2393 cc) | ||||

1973–1985

| Rally name | Special Stages | Podium finishers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Driver Co-driver |

Team Car |

Time | ||

| 42ème Rallye Automobile de Monte-Carlo 19 to 26 January 1973 Round 1 of the World Rally Championship |

18 stages 420 km |

1 | 5h 42m 04s | ||

| 2 | 5h 42m 30s | ||||

| 3 | 5h 43m 39s | ||||

| 1974 rally cancelled | |||||

| 43ème Rallye Automobile de Monte-Carlo 15 to 23 January 1975 Round 1 of the World Rally Championship |

22 stages 472 km |

1 | 6h 25m 59s | ||

| 2 | 6h 29m 05s | ||||

| 3 | 6h 29m 46s | ||||

| 44ème Rallye Automobile de Monte-Carlo 17 to 24 January 1976 Round 1 of the World Rally Championship |

23 stages 530 km |

1 | 6h 25m 10s | ||

| 2 | 6h 26m 37s | ||||

| 3 | 6h 31m 23s | ||||

| 45ème Rallye Automobile de Monte-Carlo 22 to 28 January 1977 Round 1 of the World Rally Championship Round 1 of the FIA Cup for Rally Drivers |

26 stages 506 km |

1 | 6h 36m 13s | ||

| 2 | 6h 38m 29s | ||||

| 3 | 6h 47m 07s | ||||

| 46ème Rallye Automobile de Monte-Carlo 21 to 28 January 1978 Round 1 of the World Rally Championship Round 1 of the FIA Cup for Rally Drivers |

29 stages 570 km |

1 | 6h 57m 03s | ||

| 2 | 6h 58m 55s | ||||

| 3 | 6h 59m 55s | ||||

| 47ème Rallye Automobile de Monte-Carlo 20 to 26 January 1979 Round 1 of the World Rally Championship |

30 stages 619 km |

1 | 8h 13m 38s | ||

| 2 | 8h 13m 44s | ||||

| 3 | 8h 17m 47s | ||||

| 48ème Rallye Automobile de Monte-Carlo 19 to 25 January 1980 Round 1 of the World Rally Championship |

30 stages 601 km |

1 | 8h 42m 20s | ||

| 2 | 8h 52m 58s | ||||

| 3 | 8h 53m 48s | ||||

| 49ème Rallye Automobile de Monte-Carlo 24 to 30 January 1981 Round 1 of the World Rally Championship |

32 stages 757 km |

1 | 9h 55m 55s | ||

| 2 | 9h 58m 49s | ||||

| 3 | 10h 2m 54s | ||||

| 50ème Rallye Automobile de Monte-Carlo 16 to 22 January 1982 Round 1 of the World Rally Championship |

32 stages 753 km |

1 | 8h 20m 33s | ||

| 2 | 8h 24m 22s | ||||

| 3 | 8h 32m 38s | ||||

| 51ème Rallye Automobile de Monte-Carlo 22 to 29 January 1983 Round 1 of the World Rally Championship |

30 stages 709 km |

1 | 7h 58m 57s | ||

| 2 | 8h 5m 59s | ||||

| 3 | 8h 10m 15s | ||||

| 52ème Rallye Automobile de Monte-Carlo 21 to 27 January 1984 Round 1 of the World Rally Championship |

30 stages 722 km |

1 | 8h 52m 29s | ||

| 2 | 8h 53m 53s | ||||

| 3 | 9h 5m 9s | ||||

| 53ème Rallye Automobile de Monte-Carlo 26 January to 1 February 1985 Round 1 of the World Rally Championship |

34 stages 852 km |

1 | 10h 20m 49s | ||

| 2 | 10h 26m 06s | ||||

| 3 | 10h 30m 54s | ||||

1986–1999

2000–2009

2010–2019

2020–

| Rally name | Stages | Podium finishers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Driver Co-driver |

Team Car |

Time | ||

| 88ème Rallye Automobile Monte-Carlo 23 to 26 January 2020 Round 1 of the 2020 World Rally Championship |

16 stages 304.28 km |

1 | 3h 10m 57.6s | ||

| 2 | 3h 11m 10.2s | ||||

| 3 | 3h 11m 11.9s | ||||

| 89ème Rallye Automobile Monte-Carlo 21 to 24 January 2021 Round 1 of the 2021 World Rally Championship |

14 stages 257.64 km |

1 | 2h 56m 33.7s | ||

| 2 | 2h 57m 06.3s | ||||

| 3 | 2h 57m 47.2s | ||||

- † – Event was shortened after stages were cancelled.

Multiple winners

|

|

See also

- Monte Carlo or Bust!

- Herbie Goes to Monte Carlo

- EWRC.com shows many of the results

- Further reading: 1911-1980 Monte Carlo Rally - The Golden Age, by Graham Robson (2007)

Notes

- "Latest Formula 1 Breaking News - Grandprix.com". www.grandprix.com.

- "Rallye de Monaco 1911, première édition du Monte-Carlo". pcallais.free.fr.

- Monte Carlo Rally, the golden age; Graham Robson, p99

- "Monte Carlo Rally to open 2011 IRC season". ircseries.com. Intercontinental Rally Challenge. 2010-07-19. Archived from the original on 2010-10-10. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- Motor Sport, March 1966, pages 202, 204.

- Competition Press & Autoweek, February 12, 1966, Pages 1, 6.

- "1966: Future of Monte Carlo rally in doubt". BBC News. 21 January 1966.

- MotorSport Archive, March, 1966, Pages 44.|url= http://www.motorsportmagazine.com/archive/article/march-1966/44/monte-carlo-fiasco

- The website ewrc.com gives a full list of the most frequent winners, podium winners, stage winners and the most frequent participants

- "Team LOOS INTERNATIONAL" at the 9th Rallye Monte-Carlo Historique Archived 2008-04-15 at the Wayback Machine. Loos International. Accessed May 12, 2010.

- Duijvestijn, Guus. Alpine Passes Archived 2008-04-16 at the Wayback Machine. Archived at AJ's Touring Home Page. Accessed May 12, 2010.

- Monte Carlo: Rally route Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine. Motorsport.com, January 18, 2008. Accessed May 12, 2010.

- According to an article in an unknown 1912 French newspaper stating "Arrivee du Paul Meunier. .... Il est venu du Havre ....avec sept personnes..."

- according to William Body in 1983 in Motor Sport she was the wife of a Citroën dealer

- "Honours". Automobile Club de Monaco.

- Octane Magazine (Dutch edition, No 034); Matthijs Diepraam: ‘’This participant died as a result of an accident during the 1930 RMC, when near Valence the Graham Paige was hit from behind by a Rolls Royce of another participant while changing a tyre (p118/119)

- Hamberg, Erik (1998). "Rileys svenska Monte Carlo-historia" [Riley's Swedish Monte Carlo history] (PDF). Rileybladet (in Swedish). Svenska Rileyregistret. 20 (2): 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-12-13.

- Some sources state Zamfirescu/Trevoux in 3rd place; see ewrc.com

- Lindner was chronometreur, see conam.info

- Readers' guide to who won at Monte Carlo, British Motor Corporation advertisement, Life Magazine, 14 February 1964, page 81 Retrieved from books.google.com.au on 22 December 2011

- "2009 Final Ranking". www.acm.mc. 2009-01-24. Archived from the original on 2011-05-23. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- "2010 Final Ranking". www.acm.mc. 2010-01-23. Archived from the original on 2010-03-16. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- "2011 Final Ranking". www.acm.mc. 2011-01-23. Archived from the original on 2011-05-23. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rallye Automobile Monte Carlo. |