History of Burkina Faso

The history of Burkina Faso includes the history of various kingdoms within the country, such as the Mossi kingdoms, as well as the later French colonisation of the territory and its independence as the Republic of Upper Volta in 1960.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Burkina Faso |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Sport |

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Burkina Faso | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

Ancient and medieval history

Recent archeological discoveries at Bura in southwest Niger and in adjacent southwest Burkina Faso have documented the existence of the iron-age Bura culture from the 3rd century to the 13th century. The Bura-Asinda system of settlements apparently covered the lower Niger River valley, including the Boura region of Burkina Faso. Further research is needed to understand the role this early civilization played in the ancient and medieval history of West Africa.[1]

Loropéni is a pre-European stone ruin which was linked to the gold trade. It has been declared as Burkina Faso's first World Heritage site.

From medieval times until the end of the 19th century, the region of Burkina Faso was ruled by the empire-building Mossi people, who are believed to have come up to their present location from northern Ghana, where the ethnically-related Dagomba people still live. For several centuries, Mossi peasants were both farmers and soldiers. During this time the Mossi Kingdoms successfully defended their territory, religious beliefs and social structure against forcible attempts at conquest and conversion by their Muslim neighbors to the northwest.

French Upper Volta

When the French troops of Kimberly arrived and claimed the area in 1896, Mossi resistance ended with the capture of their capital at Ouagadougou. In 1919, certain provinces from Ivory Coast were united into French Upper Volta in the French West Africa federation. In 1932, the new colony was split up for economic reasons; it was reconstituted in 1937 as an administrative division called the Upper Coast. After World War II, the Mossi actively pressured the French for separate territorial status and on September 4, 1947, Upper Volta became a French West African territory again in its own right.

A revision in the organization of French Overseas Territories began with the passage of the Basic Law (Loi Cadre) of July 23, 1956. This act was followed by reorganizational measures approved by the French parliament early in 1957 that ensured a large degree of self-government for individual territories. Upper Volta became an autonomous republic in the French community on December 11, 1958. On July 11, 1960 France agreed to Upper Volta becoming fully independent.[2]

Republic of Upper Volta

The Republic of Upper Volta declared independence on 5 August 1960. The first president, Maurice Yaméogo, was the leader of the Voltaic Democratic Union (UDV). The 1960 constitution provided for election by universal suffrage of a president and a national assembly for 5-year terms. Soon after coming to power, Yaméogo banned all political parties other than the UDV. Yaméogo's government was viewed as corrupt and said to perpetuate neo-colonialism by favoring French political and economic interests which had allowed politicians to enrich themselves but not the nation's peasants or small class of urban workers.[3]

The government lasted until 1966 when - after much unrest including mass demonstrations and strikes by students, labor unions, and civil servants - the military intervened and deposed Yaméogo in the 1966 Upper Voltan coup d'état. The coup leaders suspended the constitution, dissolved the National Assembly, and placed Lieutenant Colonel Sangoulé Lamizana at the head of a government of senior army officers. The army remained in power for 4 years; on June 14, 1970, the Voltans ratified a new constitution that established a 4-year transition period toward complete civilian rule. Lamizana remained in power throughout the 1970s as president of military or mixed civil-military governments. He faced a major crisis in the form of the Sahel drought and was sent in 1973 to the UN and the US in order to secure aid.[4] After conflict over the 1970 constitution, a new constitution was written and approved in 1977, and Lamizana was reelected by open elections in 1978.

Lamizana's government faced problems with the country's traditionally powerful trade unions and on November 25, 1980, Colonel Saye Zerbo overthrew President Lamizana in a bloodless coup. Colonel Zerbo established the Military Committee of Recovery for National Progress as the supreme governmental authority, thus eradicating the 1977 constitution.

Colonel Zerbo also encountered resistance from trade unions and was overthrown two years later on November 7, 1982, by Major Dr. Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo and the Council of Popular Salvation (CSP). The CSP continued to ban political parties and organizations, yet promised a transition to civilian rule and a new constitution.

Infighting developed between the right and left factions of the CSP. The leader of the leftists, Capt. Thomas Sankara, was appointed prime minister in January 1983, but subsequently arrested. Efforts to free him, directed by Capt. Blaise Compaoré, resulted in a military coup d'état on 4 August 1983.

The coup brought Sankara to power and his government began to implement a series of revolutionary programs which included mass-vaccinations, infrastructure improvements, the expansion of women's rights, encouragement of domestic agricultural consumption and anti-desertification projects.[5]

Burkina Faso

On 2 August 1984,[6] on President Sankara's initiative, the country's name was changed from Upper Volta to Burkina Faso (land of the upright/honest people).[7][8][9]The presidential decree was confirmed by the National Assembly on 4 August.

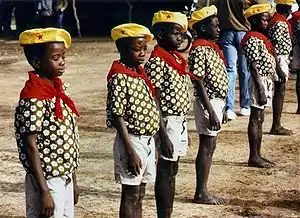

Sankara's government formed the National Council for the Revolution (CNR), with Sankara as its president, and established popular Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs). The Pioneers of the Revolution youth programme was also established.

Sankara launched an ambitious socioeconomic programme for change, one of the largest ever undertaken on the African continent.[5] His foreign policies were centred on anti-imperialism, his government denying all foreign aid, pushing for odious debt reduction, nationalising all land and mineral wealth and averting the power and influence of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. His domestic policies included a nationwide literacy campaign, land redistribution to peasants, railway and road construction and the outlawing of female genital mutilation, forced marriages and polygamy.[10][5]

Sankara pushed for agrarian self-sufficiency and promoted public health by vaccinating 2,500,000 children against meningitis, yellow fever, and measles.[10] His national agenda also included planting over 10,000,000 trees to halt the growing desertification of the Sahel. Sankara called on every village to build a medical dispensary and had over 350 communities build schools with their own labour.[5][11]

Five-day War with Mali

On Christmas Day 1985, tensions with Mali over the mineral-rich Agacher Strip erupted in a war that lasted five days and killed about 100 people. The conflict ended after mediation by President Félix Houphouët-Boigny of Ivory Coast. The conflict is known as the "Christmas war" in Burkina Faso.

Many of the strict austerity measures taken by Sankara met with growing resistance and disagreement. Despite his initial popularity and personal charisma, problems began to surface in the implementation of the revolutionary ideals.

Rule of Blaise Compaoré

The CDRs, which were formed as popular mass organizations, deteriorated in some areas into gangs of armed thugs and clashed with several trade unions. Tensions over the repressive tactics of the government and its overall direction mounted steadily. On October 15, 1987, Sankara was assassinated in a coup which brought Captain Blaise Compaoré to power.

Compaoré, Captain Henri Zongo, and Major Jean-Baptiste Boukary Lengani formed the Popular Front (FP), which pledged to continue and pursue the goals of the revolution and to "rectify" Sankara's "deviations" from the original aims. The new government, realizing the need for bourgeois support, tacitly moderated many of Sankara's policies. As part of a much-discussed political "opening" process, several political organizations, three of them non-Marxist, were accepted under an umbrella political organization created in June 1989 by the FP.

Some members of the leftist Organisation pour la Démocratie Populaire/Mouvement du Travail (ODP/MT) were against the admission of non-Marxist groups in the front. On September 18, 1989, while Compaoré was returning from a two-week trip to Asia, Lengani and Zongo were accused of plotting to overthrow the Popular Front. They were arrested and summarily executed the same night. Compaoré reorganized the government, appointed several new ministers, and assumed the portfolio of Minister of Defense and Security. On December 23, 1989, a presidential security detail arrested about 30 civilians and military personnel accused of plotting a coup in collaboration with the Burkinabe external opposition.

A new constitution, establishing the fourth republic, was adopted on June 2, 1991. Among other provisions, it called for an Assembly of People's Deputies with 107 seats (now 111). The president is chief of state, chairs a council of ministers, appoints a prime minister, who with the legislature's consent, serves as head of government. In April 2000, the constitution was amended reducing the presidential term from seven to five years, enforceable as of 2005, and allowing the president to be reelected only once. The legislative branch is a unicameral National Assembly (Assemblée Nationale) consisting of 111 seats. Members are elected by popular vote for five-year terms.

In April 2005, President Compaoré was re–elected for a third straight term. He won 80.3% of the vote, while Benewende Stanislas Sankara came a distant second with a mere 4.9%. In November 2010, President Compaoré was re–elected for a fourth straight term. He won 80.2% of the vote, while Hama Arba Diallo came a distant second with 8.2%.

In February 2011, the death of a schoolboy provoked an uprising in the entire country, lasting through April 2011, which was coupled with a military mutiny and with a strike of the magistrates. See 2011 Burkina Faso uprising.

Overthrow of Compaoré

In June 2014 Compaoré's ruling party, the CDP, called on him to organise a referendum that would allow him to alter the constitution in order to seek re-election in 2015; otherwise he would be forced to step down due to term limits.[12]

On 30 October 2014 the National Assembly was scheduled to debate an amendment to the constitution which would have enabled Compaoré to stand for re-election as President in 2015. Opponents protested this by storming the parliament building in Ouagadougou, starting fires inside it and looting offices; billowing smoke was reported to be coming from the building by the BBC.[13] Opposition spokesman Pargui Emile Paré, of the People's Movement for Socialism / Federal Party, described the protests as "Burkina Faso’s black spring, like the Arab spring".[14]

Compaoré reacted to the events by shelving the proposed constitutional changes, dissolving the government, declaring a state of emergency and offering to work with the opposition to resolve the crisis. Later in the day, the military, under General Honore Traore, announced that it would install a transitional government "in consultation with all parties" and that the National Assembly was dissolved; he foresaw "a return to the constitutional order" within a year. He did not make clear what role, if any, he envisioned for Compaoré during the transitional period.[15][16][17] Compaoré said that he was prepared to leave office at the end of the transition.[18]

On October 31 Compaoré announced he had left the presidency and that there was a "power vacuum"; he also called for a "free and transparent" election within 90 days. Yacouba Isaac Zida then took over the reins as head of state in an interim capacity.[19]

On 17 November 2014, a civilian, Michel Kafando, was chosen to replace Zida as transitional head of state, and he was sworn in on 18 November.[20] Kafando then appointed Zida as Prime Minister of Burkina Faso on 19 November 2014.[21]

On 19 July 2015, amidst tensions between the military and Prime Minister Zida, Kafando stripped Zida of the defense portfolio and took over the portfolio himself. He also took over the security portfolio, previously held by Zida's ally Auguste Denise Barry.[22] As part of the same reshuffle, he appointed Moussa Nébié to replace himself as Minister of Foreign Affairs.[23]

September 2015 failed coup d'état

On 16 September 2015, two days after a recommendation from the National Reconciliation and Reforms Commission to disband the Regiment of Presidential Security (RSP), members of the RSP detained President Kafando and Prime Minister Zida, and installed the National Council for Democracy in power with Gilbert Diendéré as its chairman.[24][25]

The military chief of staff (the chef d'état-major des armées du Burkina Faso), Brigadier General Pingrenoma Zagré, called on members of the RSP to lay down their arms, promising in a statement that they would not be harmed if they surrendered peacefully.[26]

Kafando was believed to remain under house arrest until 21 September, when he was reported to have arrived at the residence of the French ambassador.[27] The regular army issued an ultimatum to the RSP to surrender by the morning of 22 September.[28]

Kafando was reinstalled as President at a ceremony on 23 September in the presence of ECOWAS leaders.[29]

On 25 September the RSP was disbanded by government decree. On 26 September the assets of Diendéré and others associated with the coup, as well as the assets of four political parties, including the CDP, were frozen by the state prosecutor.[30] Djibril Bassolé and Eddie Komboïgo, who were barred from standing as presidential candidates, both had their assets frozen. Bassolé was arrested on 29 September for allegedly supporting the coup.[31]

2015 general election

On 13 October 2015 it was announced that general elections would be held on 29 November 2015.[32] The Congress for Democracy and Progress was banned from running a presidential candidate, but was still able to participate in the parliamentary election.

The presidential election was won by Roch Marc Christian Kaboré of the People's Movement for Progress (MPP), who received 53% of the vote in the first round, negating the need for a second round. The parliamentary election was also won by MPP, which scored 34,71% of votes and won 55 seats in the National Assembly, followed by the Union of Progress and Reform (20,53%, 33 seats) and the Congress for Democracy and Progress (13,20%, 18 seats).

Kaboré was sworn in as President on 29 December 2015. On 7 January 2016 he appointed Paul Kaba Thieba as Prime Minister.[33]

2018 status

The 2018 CIA World Factbook provides this updated summary. "Burkina Faso is a poor, landlocked country that depends on adequate rainfall. Irregular patterns of rainfall, poor soil, and the lack of adequate communications and other infrastructure contribute to the economy’s vulnerability to external shocks. About 80% of the population is engaged in subsistence farming and cotton is the main cash crop. The country has few natural resources and a weak industrial base. Cotton and gold are Burkina Faso’s key exports ...The country has seen an upswing in gold exploration, production, and exports."

"While the end of the political crisis has allowed Burkina Faso’s economy to resume positive growth, the country’s fragile security situation could put these gains at risk. Political insecurity in neighboring Mali, unreliable energy supplies, and poor transportation links pose long-term challenges." Civil unrest continued to be problematic, according to the report. "The country experienced terrorist attacks in its capital in 2016, 2017, and 2018 and continues to mobilize resources to counter terrorist threats." (In 2018, several governments were warning their citizens not to travel into the northern part of the country and into several provinces in the East Region.)[34][35] The CIA report also states that "Burkina Faso's high population growth, recurring drought, pervasive and perennial food insecurity, and limited natural resources result in poor economic prospects for the majority of its citizens". The report is optimistic in some aspects, particularly the work being done with assistance by the International Monetary Fund. "A new three-year IMF program (2018-2020), approved in 2018, will allow the government to reduce the budget deficit and preserve critical spending on social services and priority public investments."[36]

See also

- Ouagadougou history and timeline (capital and largest city)

- History of Africa

- History of West Africa

- List of heads of government of Burkina Faso

- List of heads of state of Burkina Faso

- Politics of Burkina Faso

References

- LaGamma, Alisa Verfasser. Sahel : art and empires on the shores of the Sahara. ISBN 978-1-58839-687-7. OCLC 1150817612.

- "4 AFRICAN STATES ATTAIN FREEDOM; France Gives Independence to Ivory Coast, Niger, Dahomey and Volta". nytimes.com. Retrieved April 9, 2018.

- Benin, The Congo, Burkina Faso, Politics, Economics and Society, 1989, Joan Baxter and Keith Somerville, Pinter Publishers, London and New York, (Book)

- File:Nixon, Upper Volta President Lamizana - October 15, 1973(Gerald Ford Library)(1552621).pdf

- Thomas Sankara: The Upright Man by California Newsreel

- "More (Language of the Moose people) Phrase Book". World Digital Library. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- Kingfisher Geography Encyclopedia. ISBN 1-85613-582-9. Page 170

- Manning, Patrick (1988). Francophone Sub-Saharan Africa: 1880-198. Cambridge: New York.

- The name is an amalgam of More burkina ("honest", "upright", or "incorruptible men") and Jula faso ("homeland"; literally "father's house"). The "-be" suffix in the name for the people – Burkinabe – comes from the Fula plural suffix for people, -ɓe.

- Commemorating Thomas Sankara by Farid Omar, Group for Research and Initiative for the Liberation of Africa (GRILA), November 28, 2007

- X, Mr (October 28, 2015). "Resurrecting Thomas Sankara - My Blog". My Blog. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- Burkina Faso ruling party calls for referendum on term limits, Africa, 22 June 2014, ENCA, http://www.enca.com/burkina-faso-ruling-party-calls-referendum-term-limits

- "Burkina Faso parliament set ablaze". BBC News. 30 October 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- "Protesters storm Burkina Faso's parliament". The Guardian. 30 October 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- "Burkina Faso army announces emergency measures", BBC News, 30 October 2014.

- Hervé Taoko and Alan Cowell, "Government of Burkina Faso collapses", The New York Times, 30 October 2014.

- Mathieu Bonkoungou and Joe Penney, "Burkina army imposes interim government after crowd burns parliament", Reuters, 30 October 2014.

- "Compaore says will step down as Burkina Faso president", Deutsche Welle, 30 October 2014.

- "Burkina Faso general takes over as Compaore resigns". BBC News.

- "Kafando sworn in as Burkina Faso transitional president", Reuters, 18 November 2014.

- Mathieu Bonkoungou and Nadoun Coulibaly, "Burkina Faso names army colonel Zida as prime minister", Reuters, 19 November 2014.

- "Burkina Faso reshuffles govt 3 months before polls", Deutsche Presse-Agentur, 20 July 2015.

- "Burkina Faso reshuffles government 3 months before elections", Reuters, 20 July 2015.

- Ouedraogo, Brahima (September 16, 2015). "Military detains Burkina Faso's president, prime minister weeks ahead of landmark vote". U.S. News & World Report. Associated Press. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- Coulibaly, Nadoun; Flynn, Daniel (September 16, 2015). "Burkina Faso presidential guard detains cabinet - military sources". Reuters. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- Mathieu Bonkoungou and Nadoun Coulibaly, "Burkina Faso army enters capital to disarm coup leaders", Reuters, 21 September 2015.

- "Burkina Faso army reaches capital to quell coup", BBC News, 22 September 2015.

- "Loyalist troops tell Burkina coup leaders: surrender or face attack", Reuters, 22 September 2015.

- Patrick Fort and Romaric Ollo Hien, "Burkina president resumes power after week-long coup", Agence France-Presse, 23 September 2015.

- "Burkina Faso Coup Plotters Refuse to Give Up Arms, Imperiling Deal". Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- "Burkina army enters presidential guard camp, coup leader gone". Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- "Burkina elections to be held November 29, say candidates". Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- Editorial, Reuters. "Burkina Faso's president names economist as prime minister". U.S. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- https://beta.ctvnews.ca/national/canada/2019/1/5/1_4241773.html

- "Burkina Faso Travel Advisory". Government of USA. October 11, 2016. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- "Africa - Burkina Faso". Danube Travel. December 21, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

Further reading

- Chafer, Tony. The End of Empire in French West Africa: France's Successful Decolonization. Berg (2002). ISBN 1-85973-557-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Burkina Faso. |