Muizz Street

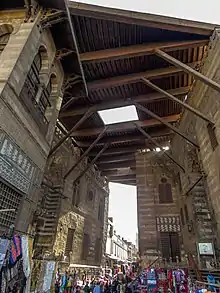

Al-Muizz li-Din Allah al-Fatimi Street (Arabic: شارع المعز لدين الله الفاطمي), or al-Muizz street for short, is a major north-to-south street in the walled city of historic Cairo, Egypt. It is one of Cairo's oldest streets as it dates back to the foundation of the city (not counting the earlier Fustat) by the Fatimid dynasty in the 10th century, under their fourth caliph, Al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah (after whom the street is named).[1] Historically, it was the most important artery of the city and was often referred to as the Qasaba (or Qasabah). It constituted the main axis of the city's economic zones where its souqs (markets) were concentrated.[1] The street's prestige also attracted the construction of many monumental religious and charitable buildings commissioned by Egypt's rulers and elites, making it a dense repository of historic Islamic architecture in Cairo.[2][1] This is especially evident in the Bayn al-Qasrayn area, which is lined with some of the most important monuments of Islamic Cairo.[2]

Description

Al-Muizz street runs from the city gate of Bab al-Futuh in the north to the gate of Bab Zuweila in the south, both entrances in the stone walls built by the vizier Badr al-Jamali in the 11th century.[1] This makes it one of the longest streets in the walled city, at approximately one kilometer long. Although the name al-Muizz street generally applies only to the street within the historic walled city, in practice the road begun by al-Muizz street continues (under various names) further south for a few kilometers, passing through the Qasaba of Radwan Bey (al-Khayamiya street), and finally ending at the great Qarafa necropolis (the Southern Cemetery or City of the Dead).[2]

History

Historically, the street was referred to as the Qasaba (a word of variable usage in Arabic, but in this case referring to a central part of the city), and constituted the main urban axis of economic and religious life in Cairo.[1]

It was laid out at the very beginning of Cairo's foundation by the Fatimid dynasty. The Fatimids conquered Egypt in 969 CE with a North African Kutama army under the command of the general, Jawhar al-Siqilli. In 970, Jawhar was responsible for planning, founding, and constructing a new city to serve as the residence and center of power for the Fatimid Caliphs. The city was named al-Mu'izziyya al-Qaahirah, the "Victorious City of al-Mu'izz", later simply called "al-Qahira", which gave us the modern name of Cairo.[3]:80 The city was located northeast of Fustat, the existing capital and main city of Egypt. Jawhar organized the city so that two great palaces for the caliphs were at its center, while between them was an important plaza known as Bayn al-Qasrayn ("Between the Two Palaces"). The city's main street connected its northern and southern gates and passed between the palaces via Bayn al-Qasrayn. In this period of the city's history, however, Cairo was a restricted city accessible only to the caliph, the army, state officials, and other persons required for the palace-city's functioning.[4][3]

After the demise of the Fatimid regime in 1171 under Salah ad-Din (Saladin), the city was opened up to common people and underwent major transformations. Over the subsequent centuries, Cairo developed into a full-scale urban center which eventually eclipsed the earlier city of Fustat. The Ayyubid sultans and their Mamluk successors, who were Sunni Muslims eager to erase the influence of the Shi'a Muslim Fatimids, progressively demolished and replaced the Fatimid structures with their own buildings and institutions. The seat of power and residence of Egypt's rulers also moved from here to the newly constructed Citadel to the south, begun by Salah ad-Din in 1176. The Qasaba avenue (al-Muizz street) went from a partly ceremonial axis to a major commercial street with shops and souqs (markets) establishing themselves along most of its length. The Khan al-Khalili commercial district developed on the Qasaba's eastern side and, partly because there was no more room to expand along that street, stretched further east towards the Mosque/shrine of al-Hussein and the Mosque of al-Azhar.[4]

Even with the removal of the royal residences, however, its symbolic importance endured and it remained one of the most prestigious sites to erect the mosques, mausoleums, madrasas and other monumental buildings commissioned by the sultans and the high elites of the regimes. During the Mamluk period in particular, the street filled up with major architectural monuments, many of which still stand today.[5] New royally-sponsored buildings continued to be built even in the 19th century under Muhammad Ali Pasha and his successors.[2]

In the 20th century, the construction of a major bypass road known as al-Azhar street, running from modern downtown Cairo in the west to al-Azhar and then later to the Salah Salem highway in the east, created a major interruption in the traditional path of al-Muizz street.[1] Today, the old city is, to some extent, split into two by this major road cutting across the former urban fabric, passing between the Khan al-Khalili area and the 16th-century Sultan al-Ghuri complex.

Historical buildings of Muizz Street

Below is a list of notable or recorded historic monuments, from many different periods, which are situated today along al-Muizz street.[2] The list goes (roughly) from the north to south, starting at Bab al-Futuh and ending at Bab Zuweila.

The following monuments are on the northern part of al-Muizz street, between Bab al-Futuh and al-Azhar street:

- Mosque of Al Hakim bi Amr Allah (1013)

- Mosque of Sulayman Agha al-Silahdar (1839)

- Bayt al-Suhaymi (1648-1796)

- Mosque of al-Aqmar (1125)

- Sabil-Kuttab of Abdel Rahman Katkhuda (1744)

- Qasr Bashtak (1339)

- Sabil of Ismail Pasha (1828)

- Hammam of Sultan Inal (1456)

- Madrasa of Al-Kamil Ayyub (1229)

- Madrasa of Barquq (1386)

- Madrasa of Al-Nasir Muhammad (1304)

- Complex of Qalawun (1285)

- Mosque of Taghri Bardi (1440)

- Sabil-Kuttab of Khusraw Pasha (1535)

- Madrasa of Al-Salih Ayyub (1250)

- Khan al-Khalili: a souq district stretching between al-Muizz street and al-Hussein square. (Dating from the Mamluk period, with many changes over time.)

- Mosque of Al-Ashraf Barsbay (1425)

- Mosque of Shaykh Ali Al-Mutahhar (1744)

The monuments below are on the southern part of al-Muizz Street, after the intersection with Al-Azhar Street:

- Madrasa of Sultan Al-Ghuri (1505)

- Mausoleum of Sultan Al-Ghuri (1505)

- Fakahani Mosque (1735)

- Sabil of Tusun Pasha (1820)

- Mosque of Muayyad (1420)

- Wikala and Sabil of Nafisa Bayda (1796)

Beyond Bab Zuweila, the path of the road continues further south but goes under different names. A few monuments, however, are clearly located along it, at the exit of Bab Zuweila:

- Zawiya of Farag Ibn Barquq (1408)

- Mosque of Salih Tala'i (1160)

- Qasaba of Radwan Bey (1650)

Rehabilitation project

Starting in 1997,[6][7] the national government carried out extensive renovations to the historical buildings, modern buildings, paving, and sewerage to turn the street into an "open-air museum". On April 24, 2008, Al-Muizz Street was rededicated as a pedestrian only zone between 8:00 am and 11:00 pm; cargo traffic is allowed outside of these hours.[8]

One of the aims of the renovations is to approximate the original appearance of the street. Buildings higher than the level of monuments have been brought down in height and painted an appropriate colour, while the street has been repaved in the original style. 34 monuments along the street and some 67 nearby have been restored. On the other hand, the nighttime appearance of the street has been modernised by the installation of state of the art refined exterior lighting on buildings.[9] To prevent the accumulation of subterranean water – the principal threat to Islamic Cairo – a state of the art drainage system has been installed.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Muizz Street. |

References

- Raymond, André (1993). Le Caire. Fayard.

- Williams, Caroline (2018). Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide (7th ed.). Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

- Brett, Michael (2017). The Fatimid Empire. Edinburgh: Edinbugh University Press.

- Denoix, Sylvie; Depaule, Jean-Charles; Tuchscherer, Michel, eds. (1999). Le Khan al-Khalili et ses environs: Un centre commercial et artisanal au Caire du XIIIe au XXe siècle. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. 2007. Cairo of the Mamluks: A History of Architecture and its Culture. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

- LA Times, 28 Sept. 1998.

- LA Times, 10 July 1998.

- Reuters

- Al-Ahram Weekly

Further reading

- Al-Ahram Weekly Online. 4–10 October 2007.

- Los Angeles Times. 28 Sept. 1997. Once-Splendid Medieval Cairo Crumbles Into Ruins.

- Los Angeles Times. 10 July 1998. Cairo Tries to Reclaim Lost Treasure Amid City’s Trash. Front page feature.

- Reuters. No date. An AOL video accompanied by a Reuters news brief.