National Library of the Philippines

The National Library of the Philippines (Filipino: Pambansang Aklatan ng Pilipinas or Aklatang Pambansa ng Pilipinas, abbreviated NLP) is the official national library of the Philippines. The complex is located in Ermita on a portion of Rizal Park facing T. M. Kalaw Avenue, neighboring culturally significant buildings such as the Museum of Philippine Political History and the National Historical Commission. Like its neighbors, it is under the jurisdiction of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA).

.svg.png.webp) | |

The facade of the library facing Kalaw Avenue | |

| Country | Philippines |

|---|---|

| Type | National library |

| Established | August 12, 1887 |

| Reference to legal mandate | Act No. 96 of the Philippine Commission (passed on March 5, 1901) |

| Location | Rizal Park, Kalaw Avenue, Ermita, Manila |

| Coordinates | 14°34′55.37″N 120°58′51.73″E |

| Branches | N/A |

| Collection | |

| Items collected | Books, journals, newspapers, magazines, sound and music recordings, databases, maps, atlases, microforms, stamps, prints, drawings, manuscripts |

| Size | 1,678,950 items, including 291,672 volumes, 210,000 books, 880,000 manuscripts, 170,000 newspaper issues, 66,000 theses and dissertations, 104,000 government publications, 53,000 photographs and 3,800 maps (2008) |

| Criteria for collection | Filipino literary and scholarly works (Filipiniana) |

| Legal deposit | Yes, provided in law by:

|

| Access and use | |

| Access requirements | Reading room services limited to Filipiniana theses and dissertations (while facilities are under renovation as of August 27, 2019) |

| Circulation | Library does not publicly circulate |

| Members | 34,500 (2007) |

| Other information | |

| Budget | ₱120.6 million (2013) |

| Director | Cesar Gilbert Q. Adriano |

| Staff | 172 |

| Website | web.nlp.gov.ph |

| Map | |

| |

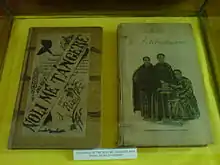

The library is notable for being the home of the original copies of the defining works of José Rizal: Noli Me Tangere, El Filibusterismo and Mi último adiós.

History

Origins (1887–1900)

The National Library of the Philippines can trace its history to the establishment of the Museo-Biblioteca de Filipinas (Museum-Library of the Philippines), established by a royal order of the Spanish government on August 12, 1887.[1][2] It opened on October 24, 1891 at the Intendencia in Intramuros, then home of the Manila Mint (as the Casa de la Moneda), with around 100 volumes and with both Julian Romero and Benito Perdiguero as director and archivist-librarian, respectively.[1]

Romero resigned in 1893 and was briefly replaced by Tomás Torres of the Escuela de Artes y Ofícios in Bacolor, Pampanga (now the Don Honorio Ventura Technological State University), who in turn was replaced by Don Pedro A. Paterno on March 31, 1894. By that time, the library had moved to a site in Quiapo near the present site of the Masjid Al-Dahab. Later on, Paterno published the first issue of the Boletin del Museo-Biblioteca de Filipinas (Bulletin of the Museum-Library of the Philippines) on January 15, 1895.[1]

The Museo-Biblioteca was abolished upon the onset of the American colonization of the Philippines. By the time of its abolition, the library held around 1,000 volumes and averaged around 25–30 visitors a day. The entire collection would later be transferred at Paterno's expense to his own private library, of which some books would form the basis for the Filipiniana collection of subsequent incarnations of the National Library.[1]

Establishment (1900–1941)

As the Philippine–American War died down and peace gradually returned to the Philippines, Americans who had come to settle in the islands saw the need for a wholesome recreational outlet. Recognizing this need, Mrs. Charles Greenleaf and several other American women organized the American Circulating Library (ACL), dedicated in memory of American soldiers who died in the Philippine–American War. The ACL opened on March 9, 1900 with 1,000 volumes donated by the Red Cross Society of California and other American organizations.[1] By 1901, the ACL's collection grew to 10,000 volumes, consisting mostly of American works of fiction, periodicals and newspapers. The rapid expansion of the library proved to be such a strain on the resources of the American Circulating Library Association of Manila, the organization running the ACL, that it was decided that the library's entire collection should be donated to the government.[1]

The Philippine Commission formalized the acceptance of the ACL's collections on March 5, 1901 through Act No. 96,[3] today observed as the birthdate of both the National Library and the Philippine public library system.[1] With the ACL now a Philippine government institution, a board of trustees and three personnel, led by librarian Nelly Y. Egbert, were appointed by the colonial government. At the same time, the library moved to Rosario Street (now Quintin Paredes Street) in Binondo before its expansion warranted its move up the street to the Hotel de Oriente on Plaza Calderón de la Barca in 1904. It was noted in the 1905 annual report of the Department of Public Instruction (the current Department of Education) that the new location "was not exactly spacious but at least it was comfortable and accessible by tramway from almost every part of the city".[1] At the same time, the ACL, acting on its mandate to make its collections available to American servicemen stationed in the Philippines, established five traveling libraries, serving various, if not unusual, clientele across the islands.[1] In November 1905, Act No. 1407 placed the library under the Bureau of Education and subsequently moved to its headquarters at the corner of Cabildo (now Muralla) and Recoletos Streets in Intramuros, on which today the offices of the Manila Bulletin stand.[1]

On June 2, 1908, Act No. 1849 was passed, mandating the consolidation of all government libraries in the Philippines into the ACL. Subsequently, Act No. 1935 was passed in 1909, renaming the ACL the Philippine Library and turning it into an autonomous body governed by a five-member Library Board. At the same time, the Act mandated the division of the library into four divisions: the law, scientific, circulating and Filipiniana divisions.[1] The newly renamed library was headed by James Alexander Robertson, an American scholar who, in collaboration with Emma Helen Blair, wrote The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898, and recognized today as both the first director of the modern National Library and the father of Philippine library science. Robertson would later abolish the library's subscription fees for books in general circulation in 1914.[1]

Act No. 2572, passed on January 31, 1916, merged the Philippine Library with two other government institutions: the Division of Archives, Patents, Copyrights and Trademarks (later to become the National Archives, the Copyright Office of the National Library and the Intellectual Property Office) and the Law Library of the Philippine Assembly, forming the Philippine Library and Museum.[4] In addition, the Philippine Library and Museum was placed under the supervision of the Department of Justice.[1] However, on December 7, 1928, Act No. 3477 was passed, splitting the Philippine Library and Museum into the National Library and the National Museum (now the National Museum of the Philippines).[4] The newly formed National Library was placed under the supervision of the Philippine Assembly, subsequently moving to the Legislative Building on Padre Burgos Street in Ermita. This arrangement continued with the convocation of the National Assembly at the dawn of the Commonwealth era in 1935. However, supervision of the National Library would return to the Department of Public Instruction in 1936.[1]

World War II (1941–1946)

The dawn of World War II and the subsequent invasion of the Philippines by the Japanese had no significant impact on the National Library, with the institution still remaining open and the government at the time making few significant changes to the library, such as the abolition of the Research and Bibliography Division and the subsequent suspension of work on the national bibliography in 1941.[1] However, by late 1944, with the impending campaign of combined American and Filipino forces to recapture the Philippines, Japanese forces stationed in Manila began setting up fortifications in large buildings, including the Legislative Building. Despite the occupation of the Legislative Building, the Japanese commanding officer permitted library officials to vacate the premises within two weeks of their occupation, with the library subsequently moving into the building housing the Philippine Normal School (now the Philippine Normal University). Two weeks later, however, Japanese troops also moved to occupy that building as well, with the same commanding officer giving library officials only until that afternoon to vacate the premises. All collections of the National Library were moved into a 1.5-cubic meter vault under the Manila City Hall, the closest building at the time. However, most of the library's Filipiniana collection, having been overlooked by moving staff and due to time constraints, was left behind at the Philippine Normal School.[1]

The Battle of Manila would prove to be disastrous to the cultural patrimony of the Philippines and the collections of the National Library in particular. Most of the library's collections were either destroyed by fires as a result of the ensuing battle between American, Filipino and Japanese forces, lost or stolen by looters afterward. Pieces lost from the library's collections included an urn where Andrés Bonifacio's remains were stored, as well as valuable Filipiniana pieces such as some of the manuscripts of José Rizal.[1] Of the 733,000 volumes the library had in its collections prior to World War II, only 36,600 remained.[5] However, luckily for library officials, a locked box containing the "crown jewels" of the National Library: the original copies of Rizal's Noli Me Tangere, El Filibusterismo and Mi último adiós, was left intact. Tiburcio Tumaneng, then the chief of the Filipiniana Division, described the event as a happy occasion.[1]

I looked around for the other box and I found it covered by a big steel cabinet which I could not lift so I only fished for the lock and found it intact. I was very happy because I knew that this second box contained the original manuscripts of the Noli, the Fili and the Último Adiós.

Word of the books' discovery by Tumaneng was relayed to Professor H. Otley Beyer, then chairman of the Committee on Salvage of Government Libraries, through officer-in-charge Luis Montilla.[1] Having found a new sense of optimism after the books' discovery, Beyer and a group of volunteers began scouring the ruins of the Legislative Building and the Philippine Normal School for any and all books they could find. However, much to their surprise, the entire collection stored under Manila City Hall disappeared, lost to looters who ransacked the ruins of public buildings. All salvaged materials were brought back to Beyer's residence on Aviles Street, near Malacañan Palace.[1]

With the return of Commonwealth rule, the National Library reopened and relocated to the site of the Old Bilibid Prison (today the Manila City Jail) on Oroquieta Street in Santa Cruz while the Legislative Building was being restored. It also sought the assistance of friendly countries to rebuild its collections. According to Concordia Sanchez in her book The Libraries of the Philippines, many countries, mainly the United States, donated many thousands of books, although some were outdated and others were too foreign for Filipino readers to understand. Although rebuilding the General Reference and Circulation Divisions was easy, rebuilding the Filipiniana Division was the hardest of all.[1]

Reconstruction (1946–1964)

In 1947, one year after the independence of the Philippines from the United States, President Manuel Roxas signed Executive Order No. 94, converting the National Library into an office under the Office of the President called the Bureau of Public Libraries.[4] The name change was done reportedly out of a sense of national shame as a result of World War II, with Roxas preferring to emphasize the library's administrative responsibilities over its cultural and historical functions.[1] Although the library was offered its original headquarters in the newly-rebuilt Legislative Building, the newly convened Congress of the Philippines forced it to relocate to the old Legislative Building at the corner of Lepanto (now Loyola) and P. Paredes Streets in Sampaloc, near the current campus of the University of the East. The Circulation Division, originally meant to cater to the residents of the city of Manila, was abolished in 1955 after it was determined that the city's residents were already adequately served by the four libraries under the supervision of the Manila city government. That same year, it was forced to relocate to the Arlegui Mansion in San Miguel, then occupied by the Department of Foreign Affairs.[1]

During this time, much of the library's Filipiniana collection was gradually restored. In 1953, two folders of Rizaliana (works pertaining to José Rizal) previously in the possession of a private Spanish citizen which contained, among others, Rizal's transcript of records, a letter from his mother, Teodora Alonso, and a letter from his wife, Josephine Bracken, were returned by the Spanish government as a gesture of friendship and goodwill. Likewise, the 400,000-piece Philippine Revolutionary Papers (PRP), also known as the Philippine Insurgent Records (PIR), were returned by the United States in 1957.[1]

After many moves throughout its history, the National Library finally moved to its present location on June 19, 1961, in commemoration of the 100th birthday of José Rizal.[4] It was renamed back to the National Library on June 18, 1964, by virtue of Republic Act No. 3873.[6][4]

Contemporary history (1964–)

Although no major changes occurred in the National Library immediately after its relocation, two significant events took place in the 1970s: first, the issuance of Presidential Decree No. 812 on October 18, 1975, which allowed the National Library to exercise the right of legal deposit, and second, the resumption of work on the Philippine National Bibliography (PNB) which had been suspended since 1941. For this purpose, the library acquired its first mainframe computer and likewise trained library staff in its use with the assistance of both UNESCO and the Technology and Livelihood Resource Center. The first edition of the PNB was published in 1977 using simplified MARC standards, and subsequently updated ever since. The library subsequently purchased three microcomputers in the 1980s and, through a Japanese grant, acquired three IBM PS/2 computers and microfilming and reprographics equipment.[1] The Library for the Blind Division was organized in 1988 and subsequently launched in 1994.[7]

Scandal arose in September 1993 when it was discovered that a researcher from the National Historical Institute (now the National Historical Commission of the Philippines), later identified as Rolando Bayhon,[8] was pilfering rare documents from the library's collections.[1] According to some library employees, the pilfering of historical documents dates back to the 1970s, when President Ferdinand Marcos began writing a book on Philippine history titled Tadhana (Destiny), using as references library materials which were subsequently not returned.[8] Having suspected widespread pilferage upon assuming the directorship in 1992, then-Director Adoracion B. Mendoza sought the assistance of the National Bureau of Investigation in recovering the stolen items. Some 700 items were recovered from an antique shop in Ermita and Bayhon was arrested. Although convicted of theft in July 1996,[8] Bayhon was sentenced in absentia and still remains at large.[9] The chief of the Filipiniana Division at the time, Maria Luisa Moral, who was believed to be involved in the scandal, was dismissed on September 25,[1] but subsequently acquitted on May 29, 2008.[9] Following Bayhon's arrest, Mendoza made several appeals calling on the Filipino people to return items pilfered from the library's collections without criminal liability. Around eight thousand documents, including the original copy of the Philippine Declaration of Independence among others, were subsequently returned to the library by various persons, including some six thousand borrowed by a professor of the University of the Philippines.[8]

In 1995, the National Library launched its local area network, consisting of a single file server and four workstations, and subsequently its online public access catalog (named Basilio, after the character in Rizal's novels) in 1998,[1] as well as its website on March 15, 2001. Following the retirement of Mendoza in 2001, Prudenciana C. Cruz was appointed director and has overseen the continued computerization of its facilities, including the opening of the library's Internet room on July 23, 2001. That same year, the library began digitization of its collections, with an initial 52,000 pieces converted into a digital format.[10] This digitization was one of the factors which led to the birth of the Philippine eLibrary, a collaboration between the National Library and the University of the Philippines, the Department of Science and Technology, the Department of Agriculture and the Commission on Higher Education, which was launched on February 4, 2004 as the Philippines' first digital library.[11] The Philippine President's Room, a section of the Filipiniana Division dedicated to works and documents pertaining to Philippine presidents, was opened on July 7, 2007.[12]

On September 26, 2007, the National Library was reorganized into nine divisions per its rationalization plan. In 2010, Republic Act No. 10078 was signed, renaming the National Library to the National Library of the Philippines.[13]

Building

In 1954, President Ramon Magsaysay issued an executive order forming the José Rizal National Centennial Commission, entrusted with the duty of "erecting a grand monument in honor of José Rizal in the capital of the Philippines". The Commission then decided to erect a cultural complex in Rizal Park with a new building housing the National Library as its centerpiece, a memorial to Rizal as an advocate of education.[14] To finance the construction of the new National Library building, the Commission conducted a nationwide public fundraising campaign, the donors being mostly schoolchildren, who were encouraged to donate ten centavos to the effort,[14] and library employees, who each donated a day's salary.[1] Because of this effort by the Commission, the National Library of the Philippines is said to be the only national library in the world built mostly out of private donations, and the only one built out of veneration to its national hero at the time of its construction.[14]

Construction on the building's foundation began on March 23, 1960 and the superstructure on September 16.[14] During construction, objections were raised over the library's location, claiming that the salinity of the air around Manila Bay would hasten the destruction of the rare books and manuscripts that would be stored there. Despite the objections, construction still continued,[14] and the new building was inaugurated on June 19, 1961, Rizal's 100th birthday, by President Carlos P. Garcia, Magsaysay's successor.[4]

The current National Library building, a six-storey, 110-foot (34 m) edifice, was designed by Hexagon Associated Architects and constructed at a cost of 5.5 million pesos.[1] With a total floor area of 198,000 square feet (18,400 m2), the library has three reading rooms and three mezzanines which currently occupy the western half of the second, third and fourth floors. Each reading room can accommodate up to 532 readers, or 1,596 in total for the entire building. The 400-seat Epifanio de los Santos Auditorium and a cafeteria are located on the sixth floor.[14] There are also provisions for administrative offices, a fumigation room, an air-conditioned photography laboratory and printing room, two music rooms and an exhibition hall.[14][15] The library's eight stack rooms have a total combined capacity of one million volumes with ample room for expansion.[14] In addition to two staircases connecting all six floors, the National Library building is equipped with a single elevator, servicing the first four floors.

Part of the National Library building's west wing is occupied by the National Archives.

Collections

The collections of the National Library of the Philippines consist of more than 210,000 books; over 880,000 manuscripts, all part of the Filipiniana Division; more than 170,000 newspaper issues from Metro Manila and across the Philippines; some 66,000 theses and dissertations; 104,000 government publications; 3,800 maps and 53,000 photographs.[12] The library's collections include large numbers of materials stored on various forms of non-print media, as well as almost 18,000 pieces for use of the Library for the Blind Division.[12]

Overall, the National Library has over 1.6 million pieces in its collections,[12] one of the largest among Philippine libraries. Accounted in its collections include valuable Rizaliana pieces, four incunabula, the original manuscript of Lupang Hinirang (the National Anthem),[16] several sets of The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898, a collection of rare Filipiniana books previously owned by the Compañía General de Tabacos de Filipinas, and the documents of five Philippine Presidents.[1] The most prized possessions of the National Library, which include Rizal's Noli Me Tangere, El Filibusterismo and Mi último adiós, three of his unfinished novels and the Philippine Declaration of Independence, are kept in a special double-combination vault at the rare documents section of the Filipiniana Division's reading room.[1][17]

A significant portion of the National Library's collections are composed of donations and works obtained through both legal deposit and copyright deposit due to the limited budget allocated for the purchase of library materials; the 2007 national budget allocation for the library allocated less than ten million pesos for the purchase of new books.[12] The library also relies on its various donors and exchange partners, which numbered 115 in 2007,[12] for expanding and diversifying its collections. The lack of a sufficient budget has affected the quality of the library's offerings: the Library for the Blind suffers from a shortage of books printed in braille,[18] while the manuscripts of Rizal's masterpieces have reportedly deteriorated due to the lack of funds to support 24-hour air conditioning to aid in its preservation.[19] In 2011, Rizal's manuscripts were restored with the help from German specialist. Major documents in the National Library of the Philippines, along with the National Archives of the Philippines, have great potential to be included in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.[20]

References

- Morallos, Chando P. (1998). Treasures of the National Library: A Brief History of the Premier Library of the Philippines. Manila: Quiapo Printing. ISBN 971-556-018-0.

- Gaceta de Madrid: num. 237, p. 594. August 25, 1887. Reference: BOE-A-1887-5774

- Act No. 96, 1901. Supreme Court E-Library

- Drake, Miriam (2003). Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science. New York: Marcel Dekker. pp. 2031–2035. ISBN 0-8247-2079-2.

- Hernandez, Vicente S. (June 3, 1999). "Trends in Philippine Library History". Conference Proceedings of the 65th IFLA Council and General Conference. 65th IFLA Council and General Conference. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- Republic Act No. 3873, 1964. Supreme Court E-Library

- Weisser, Randy (October 12, 1999). A Status Report on the Library for the Blind in the Philippines. 65th IFLA Council and General Conference. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- Mercene, Floro M. (May 30, 2008). "Losses at Nat'l Library". Manila Bulletin. Manila Bulletin Publishing Corporation. Retrieved February 17, 2009 – via Questia Online Library.

- Rufo, Aries (May 29, 2008). "Former National Library exec acquitted in pilferage case". ABS-CBN News and Current Affairs. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- National Library Annual Report. 2001.

- Antonio, Marilyn L. "Philippine eLibrary: Reaching People Beyond Borders". eGovernance Center of Excellence. Archived from the original on December 19, 2008. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- National Library Annual Report. 2007.

- Republic Act No. 10078, 2010. Supreme Court E-Library

- Velasco, Severino I. (1962). "A Philippine hero builds a National Library building". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - The National Library Brochure. 1967.

- Esplanada, Jerry E. (June 12, 2008). "Feel stirring beat of national anthem, poetry in its lyrics". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Philippine Daily Inquirer, Inc. Archived from the original on October 4, 2008. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- Ocampo, Ambeth R. (February 25, 2005). "Rizal's two unfinished novels". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Philippine Daily Inquirer, Inc. Archived from the original on May 3, 2009. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- Ortiz, Margaux C. (May 21, 2006). "Shining through in world of darkness". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Philippine Daily Inquirer, Inc. Archived from the original on May 3, 2009. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- De Guzman, Susan A. (January 8, 2007). "Saving the national treasures". Manila Bulletin. Manila Bulletin Publishing Corporation. Archived from the original on January 11, 2007. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- "Rare Books and Manuscripts Section – National Library of the Philippines". web.nlp.gov.ph. Retrieved April 23, 2018.