Netherton syndrome

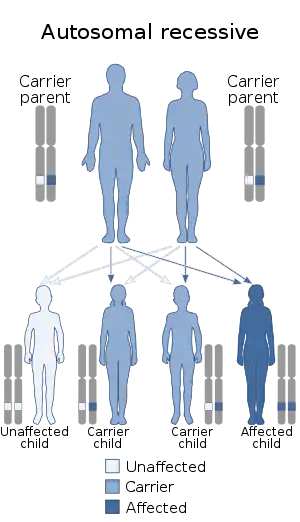

Netherton syndrome is a severe, autosomal recessive[1] form of ichthyosis associated with mutations in the SPINK5 gene.[2][3] It is named after Earl W. Netherton (1910–1985), an American dermatologist who discovered it in 1958.[4]

| Netherton syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Comèl-Netherton syndrome |

| |

| Netherton syndrome has an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Signs and symptoms

Netherton syndrome is characterized by chronic skin inflammation, universal pruritus (itch), severe dehydration, and stunted growth. Patients with this disorder tend to have a hair shaft defect (trichorrhexis invaginata), also known as "bamboo hair". The disrupted skin barrier function in affected individuals also presents a high susceptibility to infection and allergy, leading to the development of scaly, reddish skin similar to atopic dermatitis.[5] In severe cases, these atopic manifestations persist throughout the individual's life, and consequently post-natal mortality rates are high. In less severe cases, this develops into the milder ichthyosis linearis circumflexa.[3]

Netherton syndrome has recently been characterised as a primary immunodeficiency, which straddles the innate and acquired immune system, much as does Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome. A group of Netherton patients have been demonstrated to have altered immunoglobulin levels (typically high IgE and low to normal IgG) and immature natural killer cells. These Natural Killer cells have a reduced lytic function; which can be improved with regular infusions of immunoglobulin (see 'Treatment'); although the mechanism for this is not clear.[6]

Patients are more prone than healthy people to infections of all types, especially recurrent skin infections with staphylococcus. They may have more severe infections; but are not as vulnerable to opportunistic pathogens as patients with true Natural Killer cell deficiency-type SCID.

Cause

Netherton syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder associated with mutations in the SPINK5 gene, which encodes the serine protease inhibitor lympho-epithelial Kazal-type-related inhibitor (LEKTI).[2] These mutations result in a dysfunctional protein that has a reduced capacity to inhibit serine proteases expressed in the skin. Potential endogenous targets of LEKTI include KLK5, KLK7 and KLK14.[7] These enzymes are involved in various aspects of epidermal remodelling, including desquamation, PAR-2 activation and degradation of lipid hydrolases, suggesting a potential mechanism for the development of atopic manifestations characteristic of Netherton syndrome.[8]

Disease severity is determined by the level of LEKTI expression and, consequently, serine protease activity. Complete SPINK5 gene deletions have been linked to severe cases, while mutations which induce alternate splicing or create premature stop codons may lead to varying levels of severity.[8] Furthermore, LEKTI-knockout mice exhibit a phenotype similar to Netherton syndrome in humans.[5]

Treatment

There is no known cure at the moment but there are several things that can be done to relieve the symptoms. Moisturising products are very helpful to minimize the scaling/cracking, and anti-infective treatments are useful when appropriate because the skin is very susceptible to infection. Extra protein in the diet during childhood is also beneficial, to replace that which is lost through the previously mentioned "leaky" skin.

Steroid and retinoid products have been proven ineffective against Netherton syndrome, and may in fact make things worse for the affected individual.

Intravenous immunoglobulin has become established as the treatment of choice in Netherton's syndrome.[6] This therapy reduces infection; enables improvement and even resolution of the skin and hair abnormalities, and dramatically improves quality of life of the patients; although exactly how it achieves this is not known. Given this; it is possible that the reason Netherton's usually is not very severe at or shortly after birth is due to a protective effect of maternal antibodies; which cross the placenta but wane by four to six months.

See also

References

- Chao SC, Richard G, Lee JY (2005). "Netherton syndrome: report of two Taiwanese siblings with staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome and mutation of SPINK5". Br J Dermatol. 152 (1): 159–165. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06337.x. PMID 15656819. S2CID 22760789.

- Chavanas S, Bodemer C, Rochat A (June 2000). "Mutations in SPINK5, encoding a serine protease inhibitor, cause Netherton syndrome". Nat. Genet. 25 (2): 141–142. doi:10.1038/75977. PMID 10835624. S2CID 40421711.

- Freedberg, et al. (2003). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. (6th ed.). Page 496. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- Netherton, E. W. A unique case of trichorrhexis nodosa: 'bamboo hairs.'. Arch. Derm. 78: 483-487, 1958.

- Descargues P, Deraison C, Bonnart C, Kreft M, Kishibe M, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Elias P, Barrandon Y, Zambruno G, Sonnenberg A, Hovnanian A (January 2005). "Spink5-deficient mice mimic Netherton syndrome through degradation of desmoglein 1 by epidermal protease hyperactivity". Nat Genet. 37 (1): 56–65. doi:10.1038/ng1493. PMID 15619623. S2CID 11404025.

- Renner E, Hartle D, Rylaarsdam S, Young M, Monaco-Shawver L, Kleiner G, Markert ML, Stiehm ER, Belohradsky B, Upton M, Torgerson T, Orange J, Ochs H (August 2009). "Comel-Netherton syndrome defined as primary immunodeficiency". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 124 (3): 536–543. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.06.009. PMC 3685174. PMID 19683336.

- Ovaere P, Lippens S, Vandenabeele P, Declercq W (August 2009). "The emerging roles of serine protease cascades in the epidermis". Trends Biochem Sci. 34 (9): 453–63. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2009.08.001. PMID 19726197.

- Hachem JP, Wagberg F, Schmuth M, Crumrine D, Lissens W, Jayakumar A, Houben E, Mauro TM, Leonardsson G, Brattsand M, Egelrud T, Roseeuw D, Clayman GL, Feingold KR, Williams ML, Elias PM (April 2006). "Serine protease activity and residual LEKTI expression determine phenotype in Netherton syndrome". J Invest Dermatol. 126 (7): 1609–21. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700288. PMID 16601670.

- Yang T, Liang D, Koch PJ, Hohl D, Kheradmand F, Overbeek PA (October 2004). "Epidermal detachment, desmosomal dissociation, and destabilization of corneodesmosin in Spink5-/- mice". Genes Dev. 18 (19): 2354–8. doi:10.1101/gad.1232104. PMC 522985. PMID 15466487.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |