New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General

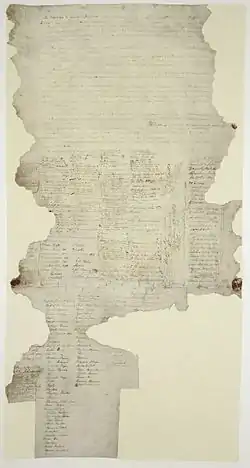

New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General, also known as the "Lands" case or "SOE" case, was a seminal New Zealand legal decision marking the beginning of the common law development of the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi.

| New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | Court of Appeal of New Zealand |

| Decided | 29 June 1987 |

| Citation(s) | [1987] 1 NZLR 641, (1987) 6 NZAR 353 |

| Transcript(s) | Available here |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting | Cooke P, Richardson, Somers, Casey and Bisson JJ |

| Keywords | |

| Treaty of Waitangi, judicial review, State-Owned Enterprises Act | |

Background

The Fourth Labour Government was embarking on a programme of commercialisation of government departments and on 1 April 1987 the State-Owned Enterprises Act 1986 came into force. The Act would allow assets and land owned by the Crown to be transferred to State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) which were government departments restructured and operated as companies.[1]

After the introduction of the State-Owned Enterprises Bill into the House of Representatives on 30 September 1986, an interim report of the Waitangi Tribunal had been given to the Minister of Māori Affairs. The Tribunal report feared that land transferred to SOEs such as the Forestry Corporation or Land Corporation would then be out of the power of the Crown to return to iwi in accordance with Tribunal recommendations because the SOE would have sold the land to a private buyer or be unwilling to sell the land back to the Crown. These land transfers would equate to a large proportion of New Zealand's land surface area.[2]

Included in the State-Owned Enterprises Act were two key sections, section 9 and section 27. Section 9 read, "9. Treaty of Waitangi — Nothing in this Act shall permit the Crown to act in a manner that is inconsistent with the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi."[3] Section 27 concerned land transferred under the Act which was subject to a Waitangi Tribunal claim prior to the Governor-General's assent of the Act, 18 December 1986.[4]

The main concern for the New Zealand Māori Council was that only where claims had been lodged before 18 December 1987 could the alienation of Māori lands be halted.

The Māori Council filed for a judicial review in March 1987 alleging in their statement of claim, "Unless restrained by this Honourable Court it is likely that the Crown will take action consequential on the exercise of statutory powers pursuant to the Act by way of the transfer of the assets the subject of existing and likely future claims before the Waitangi Tribunal in breach of the provisions of section 9 of the Act".

Judgments

The Māori Council succeeded in their appeal. The Court issued,

A declaration that the transfer of assets to State enterprises without establishing any system to consider in relation to particular assets or particular categories of assets whether such transfer would be inconsistent with the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi would be unlawful.[5]

In addition the Court directed the Crown and the Maori Council to collaborate on a,

scheme of safeguards giving reasonable assurance that lands or waters will not be transferred to State enterprises in such a way as to prejudice Maori claims that have been submitted to the Waitangi Tribunal on or after 18 December 1986 or may foreseeably be submitted to the Tribunal.[6]

In their judgments the Court recognised a number of principles of the Treaty of Waitangi, including,

- Kawanatanga and tino rangatiratanga – the right of the Crown to govern and the right of Māori to continue to exercise self-determination,[7]

- On-going partnership with obligations to act reasonably and in good faith,[8]

- Duty to remedy past breaches,

- Active protection.[9]

The Court also noted that the use of the phrase "Treaty principles" rather than terms of the Treaty, "calls for an assessment of the relationship the parties hoped to create by and reflect in that document, and an inquiry into the benefits and obligations involved in applying its language in today's changed conditions and expectation in the light of that relationship."

Significance

In December 1987 the Minister of Justice Geoffrey Palmer introduced the Treaty of Waitangi (State Enterprises) Bill into the House of Representatives to give effect to the scheme agreed between Crown and Māori Council as a result of the judgment. In December 1987, Cooke P delivered a Minute of the Court,

The Court is glad that they have succeeded. As the proposed legislation and other arrangements have been agreed, the Court has not been required to make any further ruling or to scrutinise the terms closely. We merely note that the broad principle appears to be that, if land is transferred to a State enterprise but the Waitangi Tribunal later recommend that it be returned to Maori ownership, that will be compulsory. [...] The Court hopes that this momentous agreement will be a good augury for the future of the partnership. Ka pai.[10]

In New Zealand Māori Council v Attorney-General [2013] NZSC 6, the Supreme Court, "gave weight to the SOE case jurisprudence that vests the section 9 Treaty principles section as a paramount provision that contains a broad constitutional principle. The SOE case is “of great authority and importance to the law concerning the relationship between the Crown and Maori” (at [52])."[11]

Shortly after the decision, Eddie Durie, Chief Judge of the Maori Land Court said, "Until the Court of Appeal decision two years ago which halted the transfer of assets to state-owned enterprises, Maori people had not won a case since 1847. You had a sort of judicial scoreboard - Settlers: 60, Maori: 1."[12]

Glazebrook J has described the case thus,

The Court of Appeal's decision in the Maori Council case has been viewed by New Zealand historians as one of the crucial measures that helped facilitate Maori development and identity through propelling extensive social and political change in New Zealand. It has been argued that the decision, which has been seen as giving the Treaty of Waitangi an explicit place in New Zealand jurisprudence for the first time, was one of the catalysts for the creation of a general acceptance that the state has a responsibility actively to fund the promotion of Maori language and culture and language.[13]

References

- New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General [1987] 1 NZLR 641 at 651.

- New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General [1987] 1 NZLR 641 at 653.

- New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General [1987] 1 NZLR 641 at 656.

- New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General [1987] 1 NZLR 641 at 657.

- New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General [1987] 1 NZLR 641 at 666.

- New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General [1987] 1 NZLR 641 at 666.

- New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General [1987] 1 NZLR 641 at 663.

- New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General [1987] 1 NZLR 641 at 702.

- New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General [1987] 1 NZLR 641 at 703.

- New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney-General [1987] 1 NZLR 641 at 719.

- Ruru, Jacinta (March 2013). "Partial privatisation no material impairment to remedying Treaty breaches – New Zealand Māori Council v Attorney-General [2013] NZSC 6". Māori Law Review. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "NZ Herald". 14 March 1989. p. 20.

- Glazebrook, Susan (2010). "What makes a Leading Case? The Narrow Lens of the Law or a Wider Perspective?" (PDF). VUWLR. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.