No Child Left Behind Act

The No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB)[1][2] was a U.S. Act of Congress that reauthorized the Elementary and Secondary Education Act; it included Title I provisions applying to disadvantaged students.[3] It supported standards-based education reform based on the premise that setting high standards and establishing measurable goals could improve individual outcomes in education. The Act required states to develop assessments in basic skills. To receive federal school funding, states had to give these assessments to all students at select grade levels.

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Long title | An act to close the achievement gap with accountability, flexibility, and choice, so that no child is left behind. |

|---|---|

| Acronyms (colloquial) | NCLB |

| Enacted by | the 107th United States Congress |

| Citations | |

| Public law | 107-110 |

| Statutes at Large | 30 Stat. 750, 42 Stat. 108, 48 Stat. 986, 52 Stat. 781, 73 Stat. 4, 88 Stat. 2213, 102 Stat. 130 and 357, 107 Stat. 1510, 108 Stat. 154 and 223, 112 Stat. 3076, 113 Stat. 1323, 115 Stat. 1425 to 2094 |

| Codification | |

| Acts amended | Adult Education and Family Literacy Act Age Discrimination Act of 1975 Albert Einstein Distinguished Educator Fellowship Act of 1994 Augustus F. Hawkins-Robert T. Stafford Elementary and Secondary School Improvement Amendments of 1988 Carl D. Perkins Vocational and Technical Education Act of 1998 Civil Rights Act of 1964 Communications Act of 1934 Community Services Block Grant Act Department of Education Organization Act District of Columbia College Access Act of 1999 Education Amendments of 1972 Education Amendments of 1978 Education Flexibility Partnership Act of 1999 Education for Economic Security Act Educational Research, Development, Dissemination, and Improvement Act of 1994 Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 General Education Provisions Act Goals 2000: Educate America Act Hazardous and Solid Waste Amendments of 1986 Higher Education Act of 1965 Individuals with Disabilities Education Act James Madison Memorial Fellowship Act Internal Revenue Code of 1986 Johnson–O'Malley Act of 1934 Legislative Branch Appropriations Act, 1997 McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act of 1987 Museum and Library Services Act National Agricultural Research, Extension, and Teaching Policy Act of 1977 National and Community Service Act of 1990 National Child Protection Act of 1993 National Education Statistics Act of 1994 National Environmental Education Act of 1990 Native American Languages Act Public Law 88-210 Public Law 106-400 Refugee Education Assistance Act of 1980 Rehabilitation Act of 1973 Safe Drinking Water Act School-to-Work Opportunities Act of 1994 State Dependent Care Development Grants Act Telecommunications Act of 1996 Tribally Controlled Schools Act of 1987 Toxic Substances Control Act of 1976 Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century Workforce Investment Act of 1998 |

| Titles amended | 15 U.S.C.: Commerce and Trade 20 U.S.C.: Education 42 U.S.C.: Public Health and Social Welfare 47 U.S.C.: Telegraphy |

| U.S.C. sections amended | 15 U.S.C. ch. 53, subch. I §§ 2601–2629 20 U.S.C. ch. 28 § 1001 et seq. 20 U.S.C. ch. 70 42 U.S.C. ch. 119 § 11301 et seq. 47 U.S.C. ch. 5, subch. VI § 609 47 U.S.C. ch. 5, subch. II § 251 et seq. 47 U.S.C. ch. 5, subch. I § 151 et seq. 47 U.S.C. ch. 5, subch. II § 271 et seq. |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| Major amendments | |

| Repealed on December 10, 2015 | |

| Education in the United States |

|---|

|

|

|

The act did not assert a national achievement standard—each state developed its own standards.[4] NCLB expanded the federal role in public education through further emphasis on annual testing, annual academic progress, report cards, and teacher qualifications, as well as significant changes in funding.[3]

The bill passed in the Congress with bipartisan support.[5] By 2015, bipartisan criticism had accumulated so much that a bipartisan Congress stripped away the national features of No Child Left Behind. Its replacement, the Every Student Succeeds Act, turned the remnants over to the states.[6][7]

Legislative history

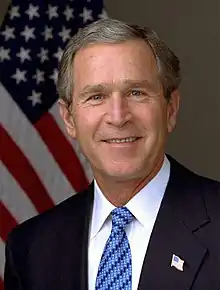

It was coauthored by Representatives John Boehner (R-OH), George Miller (D-CA), and Senators Ted Kennedy (D-MA) and Judd Gregg (R-NH). The United States House of Representatives passed the bill on December 13, 2001 (voting 381–41),[8] and the United States Senate passed it on December 18, 2001 (voting 87–10).[9] President Bush signed it into law on January 8, 2002.

Provisions of the act

No Child Left Behind requires all public schools receiving federal funding to administer a nationwide standardized test annually to all students. Schools that receive Title I funding through the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 must make Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) in test scores (e.g. each year, fifth graders must do better on standardized tests than the previous year's fifth graders).

If the school's results are repeatedly poor, then steps are taken to improve the school.[10]

- Schools that miss AYP for a second consecutive year are publicly labeled as "In Need of Improvement," and must develop a two-year improvement plan for the subject that the school is not teaching well. Students have the option to transfer to a higher performing school within the school district, if any exists.

- Missing AYP in the third year forces the school to offer free tutoring and other supplemental education services to students who are struggling.

- If a school misses its AYP target for a fourth consecutive year, the school is labelled as requiring "corrective action," which might involve wholesale replacement of staff, introduction of a new curriculum, or extending the amount of time students spend in class.

- A fifth year of failure results in planning to restructure the entire school; the plan is implemented if the school unsuccessfully hits its AYP targets for the sixth consecutive year. Common options include closing the school, turning the school into a charter school, hiring a private company to run the school, or asking the state office of education to run the school directly.

States must create AYP objectives consistent with the following requirements of the law:[11]

- States must develop AYP statewide measurable objectives for improved achievement by all students and for specific groups: economically disadvantaged students, students with disabilities, and students with limited English proficiency.

- The objectives must be set with the goal of having all students at the proficient level or above within 12 years (i.e. by the end of the 2013–14 school year).

- AYP must be primarily based on state assessments, but must also include one additional academic indicator.

- The AYP objectives must be assessed at the school level. Schools that failed to meet their AYP objective for two consecutive years are identified for improvement.

- School AYP results must be reported separately for each group of students identified above so that it can be determined whether each student group met the AYP objective.

- At least 95% of each group must participate in state assessments.

- States may aggregate up to three years of data in making AYP determinations.

The act requires states to provide "highly qualified" teachers to all students. Each state sets its own standards for what counts as "highly qualified." Similarly, the act requires states to set "one high, challenging standard" for its students. Each state decides for itself what counts as "one high, challenging standard," but the curriculum standards must be applied to all students, rather than having different standards for students in different cities or other parts of the state.

The act also requires schools to let military recruiters have students' contact information and other access to the student, if the school provides that information to universities or employers, unless the students opt out of giving military recruiters access. This portion of the law has drawn lots of criticism and has even led to political resistance. For instance, in 2003 in Santa Cruz, California, student-led efforts forced school districts to create an "opt-in" policy that required students affirm they wanted the military to have their information. This successful student organizing effort was copied in various other cities throughout the United States.[12]

Effects on teachers, schools, and school districts

Increased accountability

Supporters of the NCLB claim one of the strong positive points of the bill is the increased accountability that is required of schools and teachers. According to the legislation, schools must pass yearly tests that judge student improvement over the fiscal year. These yearly standardized tests are the main means of determining whether schools live up to required standards. If required improvements are not made, the schools face decreased funding and other punishments that contribute to the increased accountability. According to supporters, these goals help teachers and schools realize the significance and importance of the educational system and how it affects the nation. Opponents of this law say that the punishments only hurt the schools and do not contribute to the improvement of student education.

In addition to and in support of the above points, proponents claim that No Child Left Behind:

- Links state academic content standards with student outcomes

- Measures student performance: a student's progress in reading and math must be measured annually in grades 3 through 8 and at least once during high school via standardized tests

- Provides information for parents by requiring states and school districts to give parents detailed report cards on schools and districts explaining the school's AYP performance; schools must inform parents when their child is taught by a teacher or para-professional who does not meet "highly qualified" requirements

- Establishes the foundation for schools and school districts to significantly enhance parental involvement and improved administration through the use of the assessment data to drive decisions on instruction, curriculum and business practices

The commonwealth of Pennsylvania has proposed tying teacher's salaries to test scores. If a district's students do poorly, the state cuts the district's budget the following year and the teachers get a pay cut. Critics point out that if a school does poorly, reducing its budget and cutting teacher salaries will likely hamper the school's ability to improve.

School choice

- Gives options to students enrolled in schools failing to meet AYP. If a school fails to meet AYP targets two or more years running, the school must offer eligible children the chance to transfer to higher-performing local schools, receive free tutoring, or attend after-school programs.

- Gives school districts the opportunity to demonstrate proficiency, even for subgroups that do not meet State Minimum Achievement standards, through a process called "safe harbor," a precursor to growth-based or value-added assessments.

Narrow definition of research

The act requires schools to rely on scientifically based research for programs and teaching methods. The act defines this as "research that involves the application of rigorous, systematic, and objective procedures to obtain reliable and valid knowledge relevant to education activities and programs." Scientifically based research results in "replicable and applicable findings" from research that used appropriate methods to generate persuasive, empirical conclusions.[13]

Quality and distribution of teachers

Prior to the NCLB act, new teachers were typically required to have a bachelor's degree, be fully certified, and demonstrate subject matter knowledge—generally through tests. It is widely accepted that teacher knowledge has two components: specific subject matter knowledge (CK) such as an understanding of mathematics for a mathematics teacher, and pedagogical knowledge (PCK), which is knowledge of the subject of teaching/learning itself. Both types of knowledge, as well as experience in guided student teaching, help form the qualities needed by effective teachers.

Under NCLB, existing teachers—including those with tenure—were also supposed to meet standards. They could meet the same requirements set for new teachers or could meet a state-determined "...high, objective, uniform state standard of evaluation," aka HOUSSE. Downfall of the quality requirements of the NCLB legislation have received little research attention, in part because state rules require few changes from pre-existing practice. There is also little evidence that the rules have altered trends in observable teacher traits.[14] For years, American educators have been struggling to identify those teacher traits that are important contributors to student achievement. Unfortunately, there is no consensus on what traits are most important and most education policy experts agree that further research is required.

Effects on student assessment

Several of the analyses of state accountability systems that were in place before NCLB indicate that outcomes accountability led to faster growth in achievement for the states that introduced such systems.[15] The direct analysis of state test scores before and after enactment of NCLB also supports its positive impact.[16] A primary criticism asserts that NCLB reduces effective instruction and student learning by causing states to lower achievement goals and motivate teachers to "teach to the test." A primary supportive claim asserts that systematic testing provides data that shed light on which schools don't teach basic skills effectively, so that interventions can be made to improve outcomes for all students while reducing the achievement gap for disadvantaged and disabled students.[17]

Improved test scores

The Department of Education points to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) results, released in July 2005, showing improved student achievement in reading and math:[18]

- More progress was made by nine-year-olds in reading in the last five years than in the previous 28 years combined.

- America's nine-year-olds age group, posted the best scores in reading (since 1971) and math (since 1973) in the history of the report. America's 13-year-olds earned the highest math scores the test ever recorded.

- Reading and math scores for black and Hispanic nine-year-olds reached an all-time high.

- Achievement gaps in reading and math between white and black nine-year-olds and between white and Hispanic nine-year-olds are at an all-time low.

- Forty-three states and the District of Columbia either improved academically or held steady in all categories (fourth- and eighth-grade reading and fourth- and eighth-grade math).

These statistics compare 2005 with 2000 though No Child Left Behind did not even take effect until 2003. Critics point out that the increase in scores between 2000 and 2005 was roughly the same as the increase between 2003 and 2005, which calls into question how any increase can be attributed to No Child Left Behind. They also argue that some of the subgroups are cherry-picked—that in other subgroups scores remained the same or fell.[19] Also, the makers of the standardized tests have been blamed for making the tests easier so that it is easier for schools to sufficiently improve.

Education researchers Thomas Dee and Brian Jacob argue that NCLB showed statistically significant positive impact on students' performance on 4th-grade math exams (equal to two-thirds of a year's worth of growth), smaller and statistically insignificant improvements in 8th-grade math exam performance, and no discernible improvement in reading performance.[20]

Criticisms of standardized testing

Critics argue that the focus on standardized testing (all students in a state take the same test under the same conditions) encourages teachers to teach a narrow subset of skills that the school believes increases test performance, rather than achieve in-depth understanding of the overall curriculum.[21] For example, a teacher who knows that all questions on a math test are simple addition problems (e.g., What is 2 + 3?) might not invest any class time on the practical applications of addition, to leave more time for the material the test assesses. This is colloquially referred to as "teaching to the test." "Teaching to the test" has been observed to raise test scores, though not as much as other teaching techniques.[22]

Many teachers who practice "teaching to the test" misinterpret the educational outcomes the tests are designed to measure. On two state tests, New York and Michigan, and the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) almost two-thirds of eighth graders missed math word problems that required an application of the Pythagorean theorem to calculate the distance between two points.[23] The teachers correctly anticipated the content of the tests, but incorrectly assumed each test would present simplistic items rather than higher-order items.

Another problem is that outside influences often affect student performance. Students who struggle to take tests may perform well using another method of learning such as project-based learning. Sometimes, factors such as home life can affect test performance. Basing performance on one test inaccurately measures student success overall. No Child Left behind has failed to account for all these factors.[24]

Those opposed to the use of testing to determine educational achievement prefer alternatives such as subjective teacher opinions, classwork, and performance-based assessments.[25]

Under No Child Left Behind, schools were held almost exclusively accountable for absolute levels of student performance. But that meant that even schools that were making great strides with students were still labeled as "failing" just because the students had not yet made it all the way to a "proficient" level of achievement. Since 2005, the U.S. Department of Education has approved 15 states to implement growth model pilots. Each state adopted one of four distinct growth models: Trajectory, Transition Tables, Student Growth Percentiles, and Projection.[26]

The incentives for improvement also may cause states to lower their official standards. Because each state can produce its own standardized tests, a state can make its statewide tests easier to increase scores.[27] Missouri, for example, improved testing scores but openly admitted that they lowered the standards.[28] A 2007 study by the U.S. Dept. of Education indicates that the observed differences in states' reported scores is largely due to differences in the stringency of their standards.[29]

Intended effects on curriculum and standards

Improvement over local standards

Many argue that local government had failed students, necessitating federal intervention to remedy issues like teachers teaching outside their areas of expertise, and complacency in the face of continually failing schools.[30] Some local governments, notably that of New York state, have supported NCLB provisions, because local standards failed to provide adequate oversight over special education, and NCLB would let them use longitudinal data more effectively to monitor Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP).[31] States all over the United States have shown improvements in their progress as an apparent result of NCLB. For example, Wisconsin ranks first of all fifty states plus the District of Columbia, with ninety-eight percent of its schools achieving No Child Left Behind standards.[32]

Quality of education

- Increases the quality of education by requiring schools to improve their performance

- Improves quality of instruction by requiring schools to implement "scientifically based research" practices in the classroom, parent involvement programs, and professional development activities for those students that are not encouraged or expected to attend college.

- Supports early literacy through the Early Reading First initiative.

- Emphasizes reading, language arts, mathematics and science achievement as "core academic subjects."[33]

Student performance in other subjects (besides reading and math) will be measured as a part of overall progress.

Effect on arts and electives

NCLB's main focus is on skills in reading, writing, and mathematics, which are areas related to economic success. Combined with the budget crises in the late-2000s recession, some schools have cut or eliminated classes and resources for many subject areas that are not part of NCLB's accountability standards.[34] Since 2007, almost 71% of schools have reduced instruction time in subjects such as history, arts, language, and music to provide more time and resources to mathematics and English.[35][36]

In some schools, the classes remain available, but individual students who are not proficient in basic skills are sent to remedial reading or mathematics classes rather than arts, sports, or other optional subjects.

According to Paul Reville, the author of "Stop Narrowing of the Curriculum By Right-Sizing School Time," teachers are learning that students need more time to excel in the "needed" subjects. The students need more time to achieve the basic goals that should come by somewhat relevant to a student.[37]

Physical Education, on the other hand, is one of the subjects least affected.[38] Some might find this confusing because like many electives and non-core classes, No Child Left Behind does not address Physical Education directly.[39] Two reasons why Physical Education is not adversely affected include the obesity crisis in the United States that the federal government is trying to reverse through programs like First Lady Michelle Obama's Let's Move Campaign, which among other things, looks to improve the quantity and quality of physical education.[40] Secondly, there is research, including a 2005 study by Dr. Charles H. Hillmam of The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign that concludes that fitness is globally related to academic achievement.[41]

The opportunities, challenges, and risks that No Child Left Behind poses for science education in elementary and middle schools—worldwide competition insists on rapidly improving science education. Adding science assessments to the NCLB requirements may ultimately result in science being taught in more elementary schools and by more teachers than ever before. 2/3 of elementary school teachers indicated that they were not familiar with national science standards. Most concern circulates around the result that, consuming too much time for language arts and mathematics may limit children's experience—and curiosity and interest—in sciences.[42]

Limitations on local control

Both U.S. conservative and liberal critics have argued that NCLB's new standards in federalizing education set a negative precedent for further erosion of state and local control. Libertarians further argue that the federal government has no constitutional authority in education, which is why participation in NCLB is technically optional. They believe that states need not comply with NCLB so long as they forgo the federal funding that comes with it.[43]

Effects on school and students

Gifted students

NCLB pressures schools to guarantee that nearly all students meet the minimum skill levels (set by each state) in reading, writing, and arithmetic—but requires nothing beyond these minima. It provides no incentives to improve student achievement beyond the bare minimum.[44] Programs not essential for achieving mandated minimum skills are neglected or canceled by those districts.[45]

In particular, NCLB does not require any programs for gifted, talented, and other high-performing students.[46] Federal funding of gifted education decreased by a third over the law's first five years.[46] There was only one program that helped improve the gifted: they received $9.6 million. In the 2007 budget, President George W. Bush zeroed this out.[47] While NCLB is silent on the education of academically gifted students, some states (such as Arizona, California, Virginia, and Pennsylvania) require schools to identify gifted students and provide them with an appropriate education, including grade advancement. According to research, an IQ of 120 is needed.[47] In other states, such as Michigan, state funding for gifted and talented programs was cut by up to 90% in the year after the Act became law.[46]

Unrealistic goals

"There's a fallacy in the law and everybody knows it," said Alabama State Superintendent Joe Morton on Wednesday, August 11, 2010. According to the No Child Left Behind Act, by 2014, every child is supposed to test on grade level in reading and math. "That can't happen," said Morton. "You have too many variables and you have too many scenarios, and everybody knows that would never happen." Alabama State Board Member Mary Jane Caylor said, "I don't think that No Child Left Behind has benefited this state." She argued the goal of 100 percent proficiency is unattainable.[48] Charles Murray wrote of the law: "The United States Congress, acting with large bipartisan majorities, at the urging of the President, enacted as the law of the land that all children are to be above average."[49][50]

Gaming the system

The system of incentives and penalties sets up a strong motivation for schools, districts, and states to manipulate test results. For example, schools have been shown to employ "creative reclassification" of high school dropouts (to reduce unfavorable statistics).[51] For example, at Sharpstown High School in Houston, Texas, more than 1,000 students began high school as freshmen, and four years later, fewer than 300 students were enrolled in the senior class. However, none of these "missing" students from Sharpstown High were reported as dropouts.[52]

Variability in student potential and 100% compliance

The act is promoted as requiring 100% of students (including disadvantaged and special education students) within a school to reach the same state standards in reading and mathematics by 2014; detractors charge that a 100% goal is unattainable, and critics of the NCLB requirement for "one high, challenging standard" claim that some students are simply unable to perform at the given level for their age, no matter how effective the teacher is.[53] While statewide standards reduce the educational inequality between privileged and underprivileged districts in a state, they still impose a "one size fits all" standard on individual students. Particularly in states with high standards, schools can be punished for not being able to dramatically raise the achievement of students that may have below-average capabilities.

The term "all" in NCLB ended up meaning less than 100% of students, because by the time the 100% requirement was to take effect in 2015, no state had reached the goal of having 100% of student pass the proficiency bar.[54] Students who have an Individual Education Plan (IEP) and who are assessed must receive the accommodations specified in the IEP during assessment; if these accommodations do not change the nature of the assessment, then these students' scores are counted the same as any other student's score. Common acceptable changes include extended test time, testing in a quieter room, translation of math problems into the student's native language, or allowing a student to type answers instead of writing them by hand.

Simply being classified as having special education needs does not automatically exempt students from assessment. Most students with mild disabilities or physical disabilities take the same test as non-disabled students.

In addition to not requiring 5% of students to be assessed at all, regulations let schools use alternate assessments to declare up to 1% of all students proficient for the purposes of the Act.[55] States are given broad discretion in selecting alternate assessments. For example, a school may accept an Advanced Placement test for English in lieu of the English test written by the state, and simplified tests for students with significant cognitive disabilities. The Virginia Alternate Assessment Program (VAAP) and Virginia Grade Level Alternative (VGLA) options, for example, are portfolio assessments.[56]

Organizations that support NCLB assessment of disabled or limited English proficient (LEP) students say that inclusion ensures that deficiencies in the education of these disadvantaged students are identified and addressed. Opponents say that testing students with disabilities violates the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) by making students with disabilities learn the same material as non-disabled students.[57]

Children with disabilities

NCLB includes incentives to reward schools showing progress for students with disabilities and other measures to fix or provide students with alternative options than schools not meeting the needs of the disabled population.[58] The law is written so that the scores of students with IEPs (Individualized Education Plans) and 504 plans are counted just as other students' scores are counted. Schools have argued against having disabled populations involved in their AYP measurements because they claim that there are too many variables involved.

Aligning the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

Stemming from the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EAHCA) of 1975, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) was enacted in its first form in 1991, and then reenacted with new education aspects in 2006 (although still referred to as IDEA 2004). It kept the EAHCA requirements of free and accessible education for all children. The 2004 IDEA authorized formula grants to states and discretionary grants for research, technology, and training. It also required schools to use research-based interventions to assist students with disabilities.

The amount of funding each school would receive from its "Local Education Agency" for each year would be divided by the number of children with disabilities and multiplied by the number of students with disabilities participating in the schoolwide programs.[59][60]

Particularly since 2004, policymakers have sought to align IDEA with NCLB.[61] The most obvious points of alignment include the shared requirements for Highly Qualified Teachers, for establishment of goals for students with special needs, and for assessment levels for these students. In 2004, George Bush signed provisions that would define for both of these acts what was considered a "highly qualified teacher."[62]

Positive effects for students with disabilities

The National Council on Disability (NCD) looks at how NCLB and IDEA are improving outcomes for students with Down syndrome. The effects they investigate include reducing the number of students who drop out, increasing graduation rates, and effective strategies to transition students to post-secondary education. Their studies have reported that NCLB and IDEA have changed the attitudes and expectations for students with disabilities. They are pleased that students are finally included in state assessment and accountability systems. NCLB made assessments be taken "seriously," they found, as now assessments and accommodations are under review by administrators.[63]

Another organization that found positive correlations between NCLB and IDEA was the National Center on Educational Outcomes. It published a brochure for parents of students with disabilities about how the two (NCLB & IDEA) work well together because they "provide both individualized instruction and school accountability for students and disabilities." They specifically highlight the new focus on "shared responsibility of general and special education teachers," forcing schools to have disabled students more on their radar." They do acknowledge, however, that for each student to "participate in the general curriculum [of high standards for all students] and make progress toward proficiency," additional time and effort for coordination are needed.[64] The National Center on Educational Outcomes reported that now disabled students will receive "...the academic attention and resources they deserved."[65]

Particular research has been done on how the laws impact students who are deaf or hard of hearing. First, the legislation makes schools responsible for how students with disabilities score—emphasizing "...student outcomes instead of placement."[66] It also puts the public's eye on how outside programs can be utilized to improve outcomes for this underserved population, and has thus prompted more research on the effectiveness of certain in- and out-of-school interventions. For example, NCLB requirements have made researchers begin to study the effects of read aloud or interpreters on both reading and mathematics assessments, and on having students sign responses that are then recorded by a scribe.

Still, research thus far on the positive effects of NCLB/IDEA is limited. It has been aimed at young students in an attempt to find strategies to help them learn to read. Evaluations also have included a limited number of students, which make it very difficult to draw conclusions to a broader group. Evaluations also focus only on one type of disabilities.

Negative effects for students with disabilities

The National Council for Disabilities had reservations about how the regulations of NCLB fit with those of IDEA. One concern is how schools can effectively intervene and develop strategies when NCLB calls for group accountability rather than individual student attention.[67] The Individual nature of IDEA is "inconsistent with the group nature of NCLB."[68] They worry that NCLB focuses too much on standardized testing and not enough on the work-based experience necessary for obtaining jobs in the future. Also, NCLB is measured essentially by a single test score, but IDEA calls for various measures of student success.

IDEA's focus on various measures stems from its foundation in Individualized Education Plans for students with disabilities (IEP). An IEP is designed to give students with disabilities individual goals that are often not on their grade level. An IEP is intended for "developing goals and objectives that correspond to the needs of the student, and ultimately choosing a placement in the least restrictive environment possible for the student."[69] Under the IEP, students could be able to legally have lowered success criteria for academic success.

A 2006 report by the Center for Evaluation and Education Policy (CEEP) and the Indiana Institute on Disability and Community indicated that most states were not making AYP because of special education subgroups even though progress had been made toward that end. This was in effect pushing schools to cancel the inclusion model and keep special education students separate. "IDEA calls for individualized curriculum and assessments that determine success based on growth and improvement each year. NCLB, in contrast, measures all students by the same markers, which are based not on individual improvement but by proficiency in math and reading," the study states.[70] When interviewed with the Indiana University Newsroom, author of the CEEP report Sandi Cole said, "The system needs to make sense. Don't we want to know how much a child is progressing towards the standards? ... We need a system that values learning and growth over time, in addition to helping students reach high standards."[71] Cole found in her survey that NCLB encourages teachers to teach to the test, limiting curriculum choices/options, and to use the special education students as a "scapegoat" for their school not making AYP. In addition, Indiana administrators who responded to the survey indicated that NCLB testing has led to higher numbers of students with disabilities dropping out of school.

Legal journals have also commented on the incompatibility of IDEA and NCLB; some say the acts may never be reconciled with one another.[72] They point out that an IEP is designed specifically for individual student achievement, which gives the rights to parents to ensure that the schools are following the necessary protocols of Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE). They worry that not enough emphasis is being placed on the child's IEP with this setup. In Board of Education for Ottawa Township High School District 140 v. Spelling, two Illinois school districts and parents of disabled students challenged the legality of NCLB's testing requirements in light of IDEA's mandate to provide students with individualized education.[72]:5 Although students there were aligned with "proficiency" to state standards, students did not meet requirements of their IEP. Their parents feared that students were not given right to FAPE. The case questioned which better indicated progress: standardized test measures, or IEP measures? It concluded that since some students may never test on grade level, all students with disabilities should be given more options and accommodations with standardized testing than they currently receive.

Effects on racial and ethnic minority students

Attention to minority populations

- Seeks to narrow the class and racial achievement gap in the United States by creating common expectations for all. NCLB has shown mixed success in eliminating the racial achievement gap. Although test scores are improving, they are not improving equally for all races, which means that minority students are still behind.

- Requires schools and districts to focus their attention on the academic achievement of traditionally under-served groups of children, such as low-income students, students with disabilities, and students of "major racial and ethnic subgroups".[73] Each state is responsible for defining major racial and ethnic subgroups itself.[73] Many previous state-created systems of accountability measured only average school performance—so schools could be highly rated even if they had large achievement gaps between affluent and disadvantaged students.

State refusal to produce non-English assessments

All students who are learning English would have an automatic three-year window to take assessments in their native language, after which they must normally demonstrate proficiency on an English-language assessment. However, the local education authority may grant an exception to any individual English learner for another two years' testing in his or her native language on a case-by-case basis.

In practice, however, only 10 states choose to test any English language learners in their native language (almost entirely Spanish speakers). The vast majority of English language learners are given English language assessments.[74]

Many schools test or assess students with limited English proficiency even when the students are exempt from NCLB-mandated reporting, because the tests may provide useful information to the teacher and school. In certain schools with large immigrant populations, this exemption comprises a majority of young students.

NCLB testing under-reports learning at non-English-language immersion schools, particularly those that immerse students in Native American languages. NCLB requires some Native American students to take standardized tests in English.[75] In other cases, the students could be legally tested in their native language, except that the state has not paid to have the test translated.

Demographic study of AYP failure rates and requirement for failing schools

One study found that schools in California and Illinois that have not met AYP serve 75–85% minority students while schools meeting AYP have less than 40% minority students.[76] Schools that do not meet AYP are required to offer their students' parents the opportunity to transfer their students to a non-failing school within the district, but it is not required that the other school accepts the student.[77] NCLB controls the portion of federal Title I funding based upon each school meeting annual set standards. Any participating school that does not make Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) for two years must offer parents the choice to send their child to a non-failing school in the district, and after three years, must provide supplemental services, such as free tutoring or after-school assistance. After five years of not meeting AYP, the school must make dramatic changes to how the school is run, which could entail state-takeover.[78]

Funding

As part of their support for NCLB, the administration and Congress backed massive increases in funding for elementary and secondary education. Total federal education funding increased from $42.2 billion to $55.7 billion from 2001, the fiscal year before the law's passage, to fiscal year 2004.[79] A new $1 billion Reading First program was created, distributing funds to local schools to improve the teaching of reading, and over $100 million for its companion, Early Reading First.[80] Numerous other formula programs received large increases as well. This was consistent with the administration's position of funding formula programs, which distribute money to local schools for their use, and grant programs, where particular schools or groups apply directly to the federal government for funding. In total, federal funding for education increased 59.8% from 2000 to 2003.[81] The act created a new competitive-grant program called Reading First, funded at $1.02 billion in 2004, to help states and districts set up "scientific, research-based" reading programs for children in grades K–3 (with priority given to high-poverty areas). A smaller early-reading program sought to help states better prepare 3- to 5-year-olds in disadvantaged areas to read. The program's funding was later cut drastically by Congress amid budget talks.[82]

Funding Changes: Through an alteration in the Title I funding formula, the No Child Left Behind Act was expected to better target resources to school districts with high concentrations of poor children. The law also included provisions intended to give states and districts greater flexibility in how they spent a portion of their federal allotments.[82]

Funding for school technology used in classrooms as part of NCLB is administered by the Enhancing Education Through Technology Program (EETT). Funding sources are used for equipment, professional development and training for educators, and updated research. EETT allocates funds by formula to states. The states, in turn, reallocate 50% of the funds to local districts by Title I formula and 50% competitively. While districts must reserve a minimum of 25% of all EETT funds for professional development, recent studies indicate that most EETT recipients use far more than 25% of their EETT funds to train teachers to use technology and integrate it into their curricula. In fact, EETT recipients committed more than $159 million in EETT funds towards professional development during the 2004–05 school year alone. Moreover, even though EETT recipients are afforded broad discretion in their use of EETT funds, surveys show that they target EETT dollars towards improving student achievement in reading and mathematics, engaging in data-driven decision making, and launching online assessment programs.[83]

In addition, the provisions of NCLB permitted increased flexibility for state and local agencies in the use of federal education money.[84]

The NCLB increases were companions to another massive increase in federal education funding at that time. The Bush administration and congress passed very large increases in funding for the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) at the same time as the NCLB increases. IDEA Part B, a state formula-funding program that distributes money to local districts for the education of students with disabilities, was increased from $6.3 billion in 2001 to $10.1 billion in 2004.[85] Because a district's and state's performance on NCLB measures depended on improved performance by students with disabilities, particularly, students with learning disabilities, this 60 percent increase in funding was also an important part of the overall approach to NCLB implementation.

Criticisms of funding levels

Some critics claim that extra expenses are not fully reimbursed by increased levels of federal NCLB funding. Others note that funding for the law increased massively following passage[86] and that billions in funds previously allocated to particular uses could be reallocated to new uses. Even before the law's passage, Secretary of Education Rod Paige noted ensuring that children are educated remained a state responsibility regardless of federal support:

Washington is willing to help [with the additional costs of federal requirements], as we've helped before, even before we [proposed NCLB]. But this is a part of the teaching responsibility that each state has. ... Washington has offered some assistance now. In the legislation, we have ... some support to pay for the development of tests. But even if that should be looked at as a gift, it is the state responsibility to do this.

— [87]

Various early Democratic supporters of NCLB criticize its implementation, claiming it is not adequately funded by either the federal government or the states. Ted Kennedy, the legislation's initial sponsor, once stated: "The tragedy is that these long overdue reforms are finally in place, but the funds are not."[88] Susan B. Neuman, U.S. Department of Education's former Assistant Secretary for Elementary and Secondary Education, commented about her worries of NCLB in a meeting of the International Reading Association:

In [the most disadvantaged schools] in America, even the most earnest teacher has often given up because they lack every available resource that could possibly make a difference. ... When we say all children can achieve and then not give them the additional resources ... we are creating a fantasy.

— [89]

Organizations have particularly criticized the unwillingness of the federal government to "fully fund" the act. Noting that appropriations bills always originate in the House of Representatives, it is true that during the Bush Administration, neither the Senate nor the White House has even requested federal funding up to the authorized levels for several of the act's main provisions. For example, President Bush requested only $13.3 billion of a possible $22.75 billion in 2006.[90] Advocacy groups note that President Bush's 2008 budget proposal allotted $61 billion for the Education Department, cutting funding by $1.3 billion from the year before. 44 out of 50 states would have received reductions in federal funding if the budget passed as it was.[91] Specifically, funding for the Enhancing Education Through Technology Program (EETT) has continued to drop while the demand for technology in schools has increased (Technology and Learning, 2006). However, these claims focused on reallocated funds, as each of President Bush's proposed budgets increased funding for major NCLB formula programs such as Title I, including his final 2009 budget proposal.[79]

Members of Congress have viewed these authorized levels as spending caps, not spending promises. Some opponents argue that these funding shortfalls mean that schools faced with the system of escalating penalties for failing to meet testing targets are denied the resources necessary to remedy problems detected by testing. However, federal NCLB formula funding increased by billions during this period[86] and state and local funding increased by over $100 billion from school year 2001–02 through 2006–07.[92]

In fiscal year 2007, $75 billion in costs were shifted from NCLB, adding further stresses on state budgets.[93] This decrease resulted in schools cutting programs that served to educate children, which subsequently impacted the ability to meet the goals of NCLB. The decrease in funding came at a time when there was an increase in expectations for school performance. To make ends meet, many schools re-allocated funds that had been intended for other purposes (e.g., arts, sports, etc.) to achieve the national educational goals set by NCLB. Congress acknowledged these funding decreases and retroactively provided the funds to cover shortfalls, but without the guarantee of permanent aid.[94]

The number one area where funding was cut from the national budget was in Title I funding for disadvantaged students and schools.[95]

State education budgets

According to the book NCLB Meets School Realities, the act was put into action during a time of fiscal crisis for most states.[96] While states were being forced to make budget cuts, including in the area of education, they had to incur additional expenses to comply with the requirements of the NCLB Act. The funding they received from the federal government in support of NCLB was not enough to cover the added expense necessary to adhere to the new law.

Proposals for reform

The Joint Organizational Statement on No Child Left Behind[97] is a proposal by more than 135 national civil rights, education, disability advocacy, civic, labor, and religious groups that have signed on to a statement calling for major changes to the federal education law. The National Center for Fair & Open Testing (FairTest) initiated and chaired the meetings that produced the statement, originally released in October 2004. The statement's central message is that "the law's emphasis needs to shift from applying sanctions for failing to raise test scores to holding states and localities accountable for making the systemic changes that improve student achievement." The number of organizations signing the statement has nearly quadrupled since it was launched in late 2004 and continues to grow. The goal is to influence Congress, and the broader public, as the law's scheduled reauthorization approaches.

Education critic Alfie Kohn argues that the NCLB law is "unredeemable" and should be scrapped. He is quoted saying "[I]ts main effect has been to sentence poor children to an endless regimen of test-preparation drills".[98]

In February 2007, former Health and Human Services Secretary Tommy Thompson and Georgia Governor Roy Barnes, Co-Chairs of the Aspen Commission on No Child Left Behind, announced the release of the Commission's final recommendations for the reauthorization of the No Child Left Behind Act.[99] The Commission is an independent, bipartisan effort to improve NCLB and ensure it is a more useful force in closing the achievement gap that separates disadvantaged children and their peers. After a year of hearings, analysis, and research, the Commission uncovered the successes of NCLB, as well as provisions that must be significantly changed.

The Commission's goals are:

- Have effective teachers for all students, effective principals for all communities

- Accelerate progress and achievement gaps closed through improved accountability

- Move beyond status quo to effective school improvement and student options

- Have fair and accurate assessments of student progress

- Have high standards for every student in every state

- Ensure high schools prepare students for college and the workplace

- Drive progress through reliable, accurate data

- Encourage parental involvement and empowerment

The Forum on Educational Accountability (FEA), a working group of signers of the Joint Organizational Statement on NCLB has offered an alternative proposal.[100] It proposes to shift NCLB from applying sanctions for failing to raise test scores to supporting state and communities and holding them accountable as they make systemic changes that improve student learning.

While many critics and policymakers believe the NCLB legislation has major flaws, it appears the policy will be in effect for the long-term, though not without major modifications.

President Barack Obama released a blueprint for reform of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the successor to No Child Left Behind, in March 2010. Specific revisions include providing funds for states to implement a broader range of assessments to evaluate advanced academic skills, including students' abilities to conduct research, use technology, engage in scientific investigation, solve problems, and communicate effectively.

In addition, Obama proposes that the NCLB legislation lessen its stringent accountability punishments to states by focusing more on student improvement. Improvement measures would encompass assessing all children appropriately, including English language learners, minorities, and special needs students. The school system would be re-designed to consider measures beyond reading and math tests; and would promote incentives to keep students enrolled in school through graduation, rather than encouraging student drop-out to increase AYP scores.[101]

Obama's objectives also entail lowering the achievement gap between Black and White students and also increasing the federal budget by $3 billion to help schools meet the strict mandates of the bill. There has also been a proposal, put forward by the Obama administration, that states increase their academic standards after a dumbing down period, focus on re-classifying schools that have been labeled as failing, and develop a new evaluation process for teachers and educators.[102]

The federal government's gradual investment in public social provisions provides the NCLB Act a forum to deliver on its promise to improve achievement for all of its students. Education critics argue that although the legislation is marked as an improvement to the ESEA in de-segregating the quality of education in schools, it is actually harmful. The legislation has become virtually the only federal social policy meant to address wide-scale social inequities, and its policy features inevitably stigmatize both schools attended by children of the poor and children in general.

Moreover, critics further argue that the current political landscape of this country, which favors market-based solutions to social and economic problems, has eroded trust in public institutions and has undermined political support for an expansive concept of social responsibility, which subsequently results in a disinvestment in the education of the poor and privatization of American schools.

Skeptics posit that NCLB provides distinct political advantages to Democrats, whose focus on accountability offers a way for them to speak of equal opportunity and avoid being classified as the party of big government, special interests, and minority groups—a common accusation from Republicans who want to discredit what they see as the traditional Democratic agenda. Opponents posit that NCLB has inadvertently shifted the debate on education and racial inequality to traditional political alliances. Consequently, major political discord remains between those who oppose federal oversight of state and local practices and those who view NCLB in terms of civil rights and educational equality.[103]

In the plan, the Obama Administration responds to critiques that standardized testing fails to capture higher level thinking by outlining new systems of evaluation to capture more in depth assessments on student achievement.[104] His plan came on the heels of the announcement of the Race to the Top initiative, a $4.35 billion reform program financed by the Department of Education through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.[105]

Obama says that accurate assessments "...can be used to accurately measure student growth; to better measure how states, districts, schools, principals, and teachers are educating students; to help teachers adjust and focus their teaching, and to provide better information to students and their families."[104] He has pledged to support state governments in their efforts to improve standardized test provisions by upgrading the standards they are set to measure. To do this, the federal government gives states grants to help develop and implement assessments based on higher standards so they can more accurately measure school progress.[104] This mirrors provisions in the Race to the Top program that require states to measure individual achievement through sophisticated data collection from kindergarten to higher education.

While Obama plans to improve the quality of standardized testing, he does not plan to eliminate the testing requirements and accountability measures produced by standardized tests. Rather, he provides additional resources and flexibility to meet new goals.[106] Critics of Obama's reform efforts maintain that high-stakes testing is detrimental to school success across the country, because it encourages teachers to "teach to the test" and places undue pressure on teachers and schools if they fail to meet benchmarks.[107]

The re-authorization process has become somewhat of a controversy, as lawmakers and politicians continually debate about the changes that must be made to the bill to make it work best for the educational system.[108]

Waivers

In 2012, President Obama granted waivers from NCLB requirements to several states. "In exchange for that flexibility, those states 'have agreed to raise standards, improve accountability, and undertake essential reforms to improve teacher effectiveness,' the White House said in a statement."[109]

- February 9, 2012 – Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, Oklahoma, and Tennessee

- February 15, 2012 – New Mexico

- May 29, 2012 – Connecticut, Delaware, Louisiana, Maryland, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, and Rhode Island

- June 29, 2012 – Arkansas, Missouri, South Dakota, Utah, and Virginia

- July 6, 2012 – Washington and Wisconsin

Eight of the 32 NCLB waivers granted to states are conditional, meaning those states have not entirely satisfied the administration's requirements and part of their plans are under review.

The waivers of Arizona, Oregon, and Kansas are conditional, according to Acting Assistant Secretary for Elementary and Secondary Education Michael Yudin. Arizona has not yet received state board approval for teacher evaluations, and Kansas and Oregon are both still developing teacher and principal evaluation guidelines.

In addition, five states that did not complete the waiver process—and one whose application was rejected—got a one-year freeze on the rising targets for standardized test scores: Alabama, Alaska, Idaho, Iowa, Maine, and West Virginia.[110]

Replacement

On April 30, 2015, a bill was introduced to Congress to replace the No Child Left Behind Act, the Every Student Succeeds Act, which was passed by the House on December 2 and the Senate on December 9, before being signed into law by President Obama on December 10, 2015.[7][111] This bill affords states more flexibility in regards to setting their own respective standards for measuring school as well as student performance.[6][112]

See also

- Annenberg Foundation via Annenberg School Reform Institute Major Supporter of Program

- Campbell's law

- Edison Schools

- Education policy

- English immersion resources for immigrant students

- FairTest

- Learning disability

- List of standardized tests in the United States

- Mental health provisions in Title V of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001

- Ohio Graduation Test

- Prairie State Achievement Examination

- Race to the Top

- School Improvement Grant

- Stanford Achievement Test Series

References

- Pub.L. 107–110 (text) (pdf), 115 Stat. 1425, enacted January 8, 2002.

- The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (The No Child Left Behind Act of 2004)

- "No Child Left Behind: An Overview". Education Week. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- "No Child Left Behind". Archived from the original on May 2, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- "To close the achievement gap with accountability, flexibility, and choice, so that no child is left behind". Library of Congress. March 22, 2001. Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- Lyndsey Layton, "Obama signs new K–12 education law that ends No Child Left Behind" Washington Post Dec 11, 2015

- Hirschfeld Davis, Julie (December 10, 2015). "President Obama Signs Into Law a Rewrite of No Child Left Behind". The New York Times.

- "Actions Overview H.R.1 — 107th Congress (2001-2002)". Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- Dillon, Erin & Rotherham, Andy. "States' Evidence: What It Means to Make 'Adequate Yearly Progress' Under NCLB" Archived 2010-01-24 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 19, 2009.

- Linn, Robert L.; Eva L. Baker; Damian W Betebenner (August–September 2002). "Accountability Systems: Implications of Requirements of the No Child Left behind Act of 2001". Educational Researcher. 31 (6): 3–16. doi:10.3102/0013189x031006003. JSTOR 3594432. S2CID 145316506.

- http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2003/04/23/32recruit.h22.html

- Beghetto, R. (2003) Scientifically Based Research. ERIC Clearinghouse on Educational Management. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- Hanushek, Eric A.; Steven G. Rivkin (Summer 2010). "The Quality and Distribution of Teachers under the No Child Left Behind Act". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 24 (3): 133–50. doi:10.1257/jep.24.3.133. JSTOR 20799159.

- See the analyses of NAEP results in Martin Carnoy and Susanna Loeb, "Does external accountability affect student outcomes? A cross-state analysis," Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 24, no. 4 (Winter 2002): 305–31, and Eric A. Hanushek and Margaret E. Raymond, "Does school accountability lead to improved student performance?" Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 24, no. 2 (Spring 2005): 297–327.

- Center on Education Policy, Answering the Question That Matters Most: Has Student Achievement Increased Since No Child Left Behind? Washington: Center on Education Policy, June 2007).

- List of articles regarding NCLB debate

- (2006) No Child Left Behind Act Is Working Department of Education. Retrieved 6/7/07.

- Linda Perlstein, Tested

- Dee, Thomas; Jacob, Brian. "Evaluating No Child Left Behind". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - (nd) High-Stakes Assessments in Reading Archived 2006-08-27 at the Wayback Machine. International Reading Association. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- "Learning about Teaching: Initial Findings from the Measuring Effective Teaching Program". Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. December 2010. Lay summary – The Los Angeles Times (December 11, 2010). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Wiggins, G. & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design, 2nd Edition. ASCD. ISBN 978-1-4166-0035-0. pp. 42–43

- Eskelsen García, Lily; Thornton, Otha (February 13, 2015). "'No Child' has failed". Washington Post. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- (nd) What's Wrong With Standardized Testing? FairTest.org. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- Carey, Kevin (May 24, 2011). "Growth Models and Accountability: A Recipe for Remaking ESEA". Education Sector.

- (nd) New study confirms vast differences in state goals for academic ‘proficiency’ under NCLB. South Carolina Department of Education. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- (2007) Congress To Weigh 'No Child Left Behind'. Washington Post. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- "Mapping 2005 state proficiency standards onto the NAEP scales". NCES 2007-482. National Center for Education Statistics. June 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Mizell, H (2003). "NCLB: Conspiracy, Compliance, or Creativity?". Archived from the original on July 13, 2007. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- "Federal Legislation and Education in New York State 2005: No Child Left Behind Act". New York State Education Agency. 2005. Archived from the original on May 9, 2007. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- "NPR and Newshour 2008 Election Map: More about Wisconsin".

- United States. Public Law 107-110. 107th Congress, 2002.

- Beveridge, T (2010). "No Child Left Behind and Fine Arts Classes". Arts Education Policy Review. 111 (1): 4–7. doi:10.1080/10632910903228090. S2CID 73523609.

- Grey, A (2010). "No Child Left Behind in Art Education Policy: A Review of Key Recommendations for Arts Language Revisions. A". Arts Education Policy Review. 111 (1): 8–15. doi:10.1080/10632910903228132. S2CID 144288670.

- Pederson, P (2007). "What Is Measured Is Treasured: The Impact of the No Child Left Behind Act on Nonassessed Subjects". Clearing House. 80 (6): 287–91. doi:10.3200/tchs.80.6.287-291. S2CID 143019686.

- Reville, Paul (October 2007). "Stop the Narrowing of the Curriculum By 'Right-Sizing' School Time". Education Week 24 (Academic Search Premier. EBSCO.Web).

- Jack Jennings and Diane Stark Rentner, Ten Big Effects of the No Child Left Behind Act on Public Schools, Phi Delta Kappan, Vol. 88, No. 02, October 2006, pp. 110–13

- Kathy Speregen, "Physical Education in America's Public Schools" UMich.edu

- David R. Williams1, Mark B. McClellan and Alice M. Rivlin, "Beyond The Affordable Care Act: Achieving Real Improvements In Americans' Health" Health Affairs August 2010 29: 81481–88

- Hillman et al. 2005; CDE, 2001

- Marx, Ronald W.; Christopher J. Harris (May 2006). "No Child Left Behind and Science Education: Opportunities, Challenges, and Risks". The Elementary School Journal. 106 (5): 467–78. doi:10.1086/505441. JSTOR 10.1086/505441. S2CID 146637284.

- Holland, R. (2004) Critics are many, but law has solid public support. School Reform News. March 1, 2004. The Heartland Institute. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- Klein, Alyson. "No Child Left Behind Overview: Definitions, Requirements, Criticisms, and More". Education Week. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- "5 Ways No Child Left Behind Waivers Help State Education Reform - Center for American Progress". Center for American Progress. April 8, 2013. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- Cloud, John. Are We Failing Our Geniuses? from Time, July 27, 2007, pp 40–46. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- Murray, Charles (2007). "Education, Intelligence, and America's Future". Columbia International Affairs Online: 5 – via CIAO.

- Times Watchdog Report: No Child Left Behind on the way out, but not anytime soon. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- Articles & Commentary

- Marler, David (2011). "St. Louis Public Schools". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - (2004) Bush Education Ad: Going Positive, Selectively Archived 2008-01-07 at the Wayback Machine. FactCheck.org. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- Meier and Woods, D. and G. (2004). Many Children Left Behind: How the No Child Left Behind Act Is Damaging Our Children and Our Schools. Boston: Beacon Press. p. 36. ISBN 0-8070-0459-6.

- EdAccountability.org website.

- Klein, Alison (April 10, 2015). "No Child Left Behind: An Overview". Education Week. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- "VDOE :: No Child Left Behind – NCLB, Understanding AYP". Archived from the original on February 11, 2008. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- "Terminology" Virginia Department of Education website

- Harper, Liz. "No Child Left Behind’s Impact on Specialized Education". Online NewsHour. August 21, 2005. pbs.org/newshour. 20 February 2009.

- No Child Left Behind Act#Provisions of the act

- "Building The Legacy of IDEA 2004". Idea.ed.gov. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act#Alignment with No Child Left Behind

- "Reauthorized Statute Alignment With the No Child Left Behind Act" (PDF). IDEA.

- "Building The Legacy of IDEA 2004". Idea.ed.gov. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- American Youth Policy Forum; Educational Policy Institute. No Child Left Behind: Improving Educational Outcomes for Students with Disabilities (PDF). National Council on Disability. pp. 7–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 23, 2012. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

- pp. 10–12, http://www.cehd.umn.edu/nceo/onlinepubs/parents.pdf, "NCLB and IDEA: What parents need to know and do"

- p. 20, http://www.cehd.umn.edu/nceo/onlinepubs/parents.pdf, "NCLB and IDEA: What parents need to know and do"

- pp. 480–81, "Policies for Students Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing Hidden Benefits and Unintended Consequences of No Child Left Behind," http://aer.sagepub.com/content/44/3/460.full.pdf+html

- p. 5, "No Child Left Behind:Improving Educational Outcomes for Students with Disabilities" http://www.aypf.org/publications/NCLB-Disabilities.pdf Archived March 23, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- p. 23, "No Child Left Behind:Improving Educational Outcomes for Students with Disabilities" http://www.aypf.org/publications/NCLB-Disabilities.pdf Archived March 23, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Individualized Education Program

- Education Policy Brief, Closing the Achievement Gap Series: Part III, "What is the Impact of NCLB on the Inclusion of Students with Disabilities?" Cassandra Cole, http://www.ceep.indiana.edu/projects/PDF/PB_V4N11_Fall_2006_NCLB_dis.pdf Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Cassandro Cole, Interview w/ Newsroom Indiana University, http://newsinfo.iu.edu/news/page/normal/4379.html

- The Impact of No Child Left Behind on IDEA's Guarantee of Free, Appropriate Public Education for Students with Disabilities: A Critical Review of Recent Case Law (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on January 30, 2012, retrieved January 23, 2020

- "Charting the Course: States Decide Major Provisions Under No Child Left Behind". U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved April 9, 2008.

- Crawford, J. (nd) No Child Left Behind: Misguided Approach to School Accountability for English Language Learners Archived 2013-04-08 at the Wayback Machine. National Association for Bilingual Education. Retrieved June 7, 2007.

- "Native American Languages Act: Twenty Years Later, Has It Made a Difference?". Cultural Survival. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- Owens, A., & Sunderman, G. L. (2006). School Accountability under NCLB: Aid or Obstacle for Measuring Racial Equity? Cambridge, MA: Civil Rights Project at Harvard University.

- Knaus, Christopher. (2007). Still Segregated Still Unequal: Analyzing the Impact of No Child Left Behind on African American Students. University of California, Berkeley: National Urban League.

- U.S. Department of Education: The Condition of Education 2006.

- U.S. Department of Education, Fiscal Year 2009 Budget Proposal .

- U.S. Department of Education, Fiscal Year 2005 Budget Proposal

-

"Archived:Introduction: No Child Left Behind". US Department of Education. Retrieved February 23, 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "No Child Left Behind: An Overview". Education Week. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- "Support the Enhancing Education Through Technology Program Restore Funding to $496 million FY 05 Level" (PDF). Software & Information Industry Association (SIIA). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 9, 2008. Retrieved July 6, 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) -

"Archived:Introduction: No Child Left Behind". US Department of Education. December 19, 2005. Retrieved February 23, 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - U.S. Department of Education, Fiscal Year 2007 Budget Proposal

- U.S. Department of Education, Elementary and Secondary Education Act Budget Table. 2006. 7 April 2009.

- "Frontline. Testing Our Schools". March 28, 2002.

- (nd) Leaving No Child Left Behind: States charged with implementing Bush’s national education plan balk at the cost of compliance. Archived October 10, 2006, at the Wayback Machine The American Conservative. Retrieved 6/7/07.

- "Bush Education Ad: Going Positive, Selectively". FactCheck. 2004. Archived from the original on January 7, 2008. Retrieved December 29, 2007.

- (nd) Funding Archived 2006-10-19 at the Wayback Machine. American Federation of Teachers. Retrieved 6/7/07.

- Center for American Progress The Targets of Bush's Education Cuts.

- National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics 2007

- Monitor Overview

- "Funding Stagnant for No Child Left Behind Program". NPR. August 20, 2007. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- Archived November 20, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Sunderman, Gail L.; James S. Kim; Gary Orfield (2005). NCLB meets school realities: lessons from the field. Corwin Press. p. 10. ISBN 1-4129-1555-4.

- "Joint Organizational Statement on No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act". October 21, 2004. Retrieved January 3, 2008.

- NCLB: 'Too Destructive to Salvage', USA Today, May 31, 2007. Retrieved 6/7/07.

- Beyond NCLB: Fulfilling the Promise to Our Nation's Children Archived 2007-06-08 at the Wayback Machine, February, 2007. Retrieved 6/8/07.

- "Forum on Educational Accountability". Retrieved January 3, 2008.

- Weinstein, A. "Obama on No Child Left Behind Act", "Education.com, Inc." (2006).

- Dillon, Sam. "No Child Left Behind Act". The New York Times.

- Lowe, R. and Kantor, H. (2006). From New Deal to No Deal: No Child Left Behind Act and the Devolution of Responsibility for Equal Opportunity. 76:4. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Educational Review.

- U.S. Department of Education "ESEA Blueprint for Reform", (2010).

- Lohman, J. "Comparing No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top.", "OLR Research Report" (4 June 2010).

- Russell Chaddock, G. "Obama’s No Child Left Behind Revise: A Little More Flexibility", "The Christian Science Monitor". (2010).

- Ravitch, D. "Dictating to the Schools: A Look at the Effects of the Bush and Obama Administrations on Schools" Archived 2011-08-10 at the Wayback Machine, "Virginia Journal of Education". (November 2010).

- "NCLB's Lost Decade Report". FairTest. December 30, 2011. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- "Obama to push 'No Child Left Behind' overhaul". CNN. March 15, 2010. Archived from the original on February 14, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- 07/19/2012 12:01 am Updated: 08/13/2012 11:04 am (July 19, 2012). "No Child Left Behind Waivers Granted To 33 U.S. States, Some With Strings Attached". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- Lamar, Sen Alexander (April 30, 2015). "S.1177 114th Congress (2015–2016): Every Student Succeeds Act". congress.gov. Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- Nelson, Libby (December 2, 2015). "Congress is getting rid of No Child Left Behind. Here's what will replace it". Vox. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

Further reading

- Mcguinn, Patrick J. No Child Left Behind And the Transformation of Federal Education Policy, 1965–2005 (2006) excerpt and text search

- Rhodes, Jesse H. An Education in Politics: The Origins and Evolution of No Child Left Behind (Cornell University Press; 2012) 264 pages; explores role of civil-rights activists, business leaders, and education experts in passing the legislation.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Lewis, T. (2010). Obama Administration to Push for NCLB Reauthorization This Year. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- Klein, A. (2015). No Child Left Behind: An Overview. Education Week. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- Klein, A. (2015). ESEA's 50-Year Legacy a Blend of Idealism, Policy Tensions. Education Week. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- Klein, A. (2015). The Nation's Main K–12 Law: A Timeline of the ESEA. Education Week. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- No Child Left Behind news. Education Week.

- Brenneman, R. (2015). Rebranding No Child Left Behind a Tough Marketing Call. Education Week. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- Government

- NCLB Desktop Reference (online version, includes Microsoft documents and PDF links)

- Remarks by President Bush at signing ceremony

- President Discusses No Child Left Behind and High School Initiatives, Speech text and video, January 12, 2005

- Interest groups