Ocracoke, North Carolina

Ocracoke /ˈoʊkrəkoʊk/ [3] is a census-designated place (CDP) and unincorporated town located at the southern end of Ocracoke Island, located entirely within Hyde County, North Carolina, in the United States. The population was 948 as of the 2010 census.[4] As of 2014, Ocracoke's population was estimated at 591. Ocracoke Island was the location of the pirate Blackbeard's death in November 1718.[5][6][7][8][9]

Ocracoke, North Carolina | |

|---|---|

| |

Ocracoke  Ocracoke | |

| Coordinates: 35°6′46″N 75°58′33″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | North Carolina |

| County | Hyde |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9.6 sq mi (24.9 km2) |

| • Land | 8.6 sq mi (22.3 km2) |

| • Water | 1.0 sq mi (2.6 km2) |

| Elevation | 3 ft (1 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 948 |

| • Density | 110/sq mi (42.6/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| ZIP Code | 27960 |

| Area code(s) | 252 |

| FIPS code | 37-48740[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1021718[2] |

| Demonym | Ococker |

| Website | ocracokeisland |

In early September 2019, Ocracoke Island fell victim to Hurricane Dorian destroying about 1,000 feet of pavement along NC 12. Afterwards, Ocracoke Island was closed to visitors for contractors to repair the road and dune line. Normal access was restored as of December 5, 2019.[10]

History

The Outer Banks area was occasionally visited by Algonquian-speaking Indians but was never permanently settled. Ocracoke was called Wokokkon[11] and was used as a subsistence hunting and fishing ground for the Hatterask Indians. Yaupon Tea or Black Drink was made from the dried leaves of the indigenous yaupon, a native holly, and was used ceremonially by the Indians in the area. Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano described the area in detail in 1524. He was unable to navigate the shallow inlets leading into Pamlico Sound.[12][13]

In 1585, Sir Walter Raleigh's ship the Tiger ran aground on a sand bar in Ocracoke Inlet and was forced to land on the island for repairs.[14] English colonists attempted a settlement at Roanoke Island in the late 16th century, but it failed. This effectively halted European settlement in the area until 1663, when the Carolina Colony was chartered by King Charles II. However, remote Ocracoke Island was not permanently settled until 1750, being a pirate haven at times before then. It was a favorite anchorage of Edward Teach, better known as the pirate Blackbeard.[15] He was killed on the island in a fierce battle with troops from Virginia on November 22, 1718.[16] The grounds of the Springer's Point Nature Preserve were said to be his hide-out.[17]

The state assembly established Pilot Town in 1715.[18] Throughout the mid-to-late 18th century, the island was home to a number of especially skilled schooner pilots who could get smaller ships through the inlet to Pamlico Sound. As population increased on the mainland, demand increased for shipment of goods from ocean-going vessels. Warehouses were built to hold goods off-loaded from larger ships offshore and then loaded onto smaller schooners to be delivered to plantations and towns along the mainland rivers.[19]

By the late 19th century, the shipping business was gone, and the United States Life-Saving Service became a major source of steady income for local men.[20] Fishing became more important to the livelihood of the area, including charters for tourists.[21]

The Ocracoke Historic District, Ocracoke Light Station, and Salter-Battle Hunting and Fishing Lodge are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[22] Major hurricanes struck the island in August and September 1933, September 1944, and August 1949. The first-person accounts of these storms were recorded on the walls of the "Hurricane House".[23]

Fort Ocracoke

Fort Ocracoke, a Confederate fortification constructed at the beginning of the American Civil War, was situated on Beacon Island in Ocracoke Inlet, two miles to the west-southwest of Ocracoke village. The octagonally shaped fort was built on a previous War of 1812 site. At one point nearly 500 Confederate troops were stationed in and around Ocracoke and the fort. The Confederates abandoned and partially destroyed the fort in August 1861 after Union victories on nearby Hatteras Island. Union forces razed it a month later on September 17, 1861. Beacon Island and the fort subsided beneath the waves of the inlet after the 1933 hurricanes that struck the area.[24] The remnants of Fort Ocracoke were relocated and identified in 1998 by the Surface Interval Diving Company.[25]

Geography

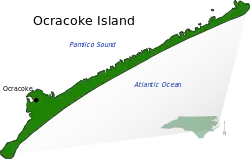

The island of Ocracoke is a part of the Outer Banks of North Carolina. At various times throughout recorded history the barrier island now known as Ocracoke has been part of Hatteras Island. The "Old Hatteras Inlet" opened prior to 1657 south of the current inlet separating Ocracoke from Hatteras, but closed around 1764 causing the islands to be reconnected. Ocracoke remained connected to Hatteras until Wells Creek Inlet opened in the 1840s and later closed. The modern "Hatteras Inlet" that separates the two islands was formed on September 7, 1846 by a violent gale. This massive storm, known in Cuba as 1846 Havana hurricane and along the East Coast of the United States as the Great Gale of 1846, was the same storm that opened Oregon Inlet.[26]

It is one of the most remote islands in the Outer Banks, as it can only be reached by one of three public ferries (two of which are toll ferries), private boat, or private plane. Other than the village of Ocracoke and a few other areas (a ferry terminal, a pony pen, a small runway), the entire island is part of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore.[27][28]

The village of Ocracoke is located around a small sheltered harbor called Silver Lake, with a second smaller residential area built around a series of man-made canals called Oyster Creek. The village is located at the widest point of the island, protected from the Atlantic Ocean by sand dunes and a salt marsh. The average height of the island is less than five feet (1.5 m) above sea level, and many of the buildings on the island are built on pilings to lift them off the ground. Flooding is a risk during both hurricanes and large storms. Ocracoke Light is situated near Silver Lake and has remained in continuous operation since 1823.[29]

The island is home to a British cemetery. During World War II, German submarines sank several British ships including HMT Bedfordshire, and the bodies of British sailors were washed ashore.[30] They were buried in a cemetery on the island. A lease for the 2,290-square-foot (213 m2) plot, where a British flag flies at all times, was given to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission for as long as the land remained a cemetery, and the small site officially became a British cemetery. The United States Coast Guard station on Ocracoke Island takes care of the property.[31] A memorial ceremony is held each year in May.[32]

Ocracoke village is located at 35°6′46″N 75°58′33″W (35.112687, -75.975895).[33] The United States Census Bureau counts the entire island as a census-designated place (CDP), with a total area of 9.6 square miles (24.9 km2). 8.6 square miles (22.3 km2) of the area is land, and 1.0 square mile (2.6 km2), or 10.58%, is water.[4]

Climate

Ocracoke has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) with hot, humid summers and cool, windy winters. Precipitation is plentiful year round and peaks during the months of August and September. The record high and low are 99 °F (37 °C) and 13 °F (−11 °C) and occurred on the dates August 18 & 22, 1975 and February 20th, 2015. The highest minimum temperature recorded is 84 °F (29 °C) and occurred on July 2, 1973. The lowest maximum temperature recorded is 22 °F (−6 °C) and occurred on February 20, 2015. The highest daily snowfall recorded is 9 in (23 cm) and happened on January 24, 2003. The highest daily snow depth also occurred on January 24, 2003 and as 9 inches, with the snow sticking on the ground for 5 days in total. The first and last average dates for a freeze are December 21 and March 3, giving Ocracoke an average growing season of 293 days, though some years don't record a freeze, with the recent winters of 2015–2016, 2016–2017, 2017–2018, and 2018–2019 not recording one. The average first and last dates for a hot 80 °F (27 °C) temperature are May 9 and October 16. The water temperature averages 81.7 °F (27.6 °C) in August to 53.4 °F (11.9 °C) in February, and usually is never above 85 °F (29 °C) or below 50 °F (10 °C), though due to the island's close proximity to Cape Hatteras where the warm Gulf Stream and the cold Labrador Current meet, water temperatures commonly fluctuate year round. The ocean is usually comfortable for swimming from late May into early October.[34][35]

| Climate data for Ocracoke, North Carolina (1981–2010 normals, extremes 1957–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 74 (23) |

80 (27) |

80 (27) |

85 (29) |

94 (34) |

96 (36) |

98 (37) |

99 (37) |

96 (36) |

87 (31) |

83 (28) |

77 (25) |

99 (37) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 49.6 (9.8) |

52.9 (11.6) |

58.5 (14.7) |

67.1 (19.5) |

73.8 (23.2) |

81.3 (27.4) |

85.7 (29.8) |

84.5 (29.2) |

80.0 (26.7) |

71.1 (21.7) |

62.3 (16.8) |

54.5 (12.5) |

68.4 (20.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 43.8 (6.6) |

46.1 (7.8) |

52.0 (11.1) |

60.3 (15.7) |

67.6 (19.8) |

75.4 (24.1) |

79.7 (26.5) |

78.4 (25.8) |

74.4 (23.6) |

65.2 (18.4) |

56.1 (13.4) |

48.1 (8.9) |

62.3 (16.8) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 38.0 (3.3) |

39.2 (4.0) |

45.5 (7.5) |

53.5 (11.9) |

61.4 (16.3) |

69.6 (20.9) |

73.7 (23.2) |

72.3 (22.4) |

68.8 (20.4) |

59.3 (15.2) |

49.9 (9.9) |

41.8 (5.4) |

56.1 (13.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 14 (−10) |

13 (−11) |

21 (−6) |

28 (−2) |

37 (3) |

48 (9) |

60 (16) |

57 (14) |

50 (10) |

36 (2) |

25 (−4) |

17 (−8) |

13 (−11) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.04 (103) |

3.77 (96) |

4.89 (124) |

3.96 (101) |

4.13 (105) |

4.07 (103) |

5.15 (131) |

7.80 (198) |

6.88 (175) |

4.97 (126) |

4.63 (118) |

3.90 (99) |

58.19 (1,478) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 8.8 | 8.5 | 8.4 | 7.7 | 7.3 | 8.2 | 10.6 | 10.1 | 10.3 | 7.3 | 7.5 | 9.7 | 104.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 70.9 | 70.0 | 67.9 | 68.3 | 71.4 | 74.8 | 77.2 | 76.1 | 73.9 | 71.0 | 72.5 | 71.1 | 72.1 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 36.9 (2.7) |

38.3 (3.5) |

42.6 (5.9) |

50.3 (10.2) |

58.8 (14.9) |

67.7 (19.8) |

72.3 (22.4) |

71.2 (21.8) |

66.5 (19.2) |

57.0 (13.9) |

49.5 (9.7) |

41.0 (5.0) |

54.4 (12.4) |

| Source 1: NOAA[36][37] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: PRISM (humidity and dew point)[38] | |||||||||||||

Transportation

A single paved two-lane road, NC 12, runs from the village at the southwestern end of the island to the ferry dock at the northeastern tip of the island, where a 1-hour-long free ferry connects to Hatteras Island. The second ferry dock, located in the village, has toll connections to Swan Quarter, North Carolina, on the mainland and Cedar Island, near Atlantic, North Carolina.

A passenger ferry operates across Ocracoke Inlet to the deserted village of Portsmouth, at the northern end of the Core Banks.

Ocracoke Island Airport (FAA Identifier W95) is located slightly southeast of the village, allowing small aircraft to land.

Economy

Tourism

The economy of Ocracoke Island is based almost entirely on tourism.[39] During the winter, the population shrinks and only a few businesses remain open. During the spring, summer, and early fall, an influx of tourists occupies hotels, campgrounds and weekly rental houses—and day visitors arrive by ferry from Hatteras Island. Several bars, a brewery, dozens of restaurants, and many shops, stores and other tourist-based businesses open for the tourist season. Visitors can find many shops that feature local, handmade goods, as well as imported artisanal goods and rare antiques, unusual for such a small island.[40]

Fishing

Commercial fishing contributes to the local economy with chartered sport fishing drawing tourism. With easy access to Pamlico Sound, the Atlantic coast and the Gulf Stream, Ocracoke offers various fishing opportunities, from small Sound fish to tuna and drum.[41]

World records

On November 4, 1987, the world record 13-pound (5.9 kg) Spanish mackerel was caught on a boat owned by Woody Outlaw off Ocracoke.[42] The fish that set this world record exceeded the previous record by almost 20%.[42]

Winter economy

During the winter, the island's only main employers are construction, the NC Department of Transportation, and the businesses that support the small population. Many islanders use the winter as time off, since they tend to work between 60 and 80 hours a week during the tourist season.[43][44]

Local dialect

Ocracoke Island and other parts of the Outer Banks historically have a distinct dialect of English, often referred to as a brogue.[45] The dialect is known as the High Tider dialect, after the characteristic phrase "high tide" (often pronounced "hoi toide"[46]). Due to the influx of tourists and greater contact with the mainland in recent years, however, the brogue has been increasingly influenced by outside dialects.[47]

Demographics

As of 2010, there were 948 people living in the CDP.[48][49] The population density as of 2000 was 80.4 people per square mile (31.1/km2). In 2000, there were 784 housing units at an average density of 82.0/sq mi (31.7/km2) in 2000. As of 2010, the racial makeup of the CDP was 96.2% White, 1.6% African American, 0.6% from two or more races, 0.4% from Native American, and 0.2% Asian. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 19.1% of the population.[48][49]

There were 370 households, out of which 17.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.8% were married couples living together, 8.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 40.8% were non-families. 30.8% of all households were composed of individuals, and 8.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.08 and the average family size was 2.55.

In the CDP, the population was spread out, with 13.0% under the age of 18, 6.1% from 18 to 24, 28.3% from 25 to 44, 34.6% from 45 to 64, and 17.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 46 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.0 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $34,315, and the median income for a family was $38,750. Males had a median income of $26,667 versus $25,625 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $18,032. About 7.7% of families and 9.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.8% of those under age 18 and 10.4% of those age 65 or over.

Public services

The residents of Ocracoke Island are served by the Ocracoke School (K-12), part of the Hyde County Schools, with a student population of 186 as of 2019.[50]

The island also has a small airport located southeast of the village on NC 12.[51] Hyde County maintains the Ocracoke Volunteer Fire Department located on Highway 12.[52]

Events

In Ocracoke, figs and fig cake are a prominent part of the town's cuisine, and the town has an annual fig festival that includes a fig cake contest.[53]

Media

Ocracoke is home to one radio station, WOVV.[54] The studios of WOVV, branded as "Ocracoke Community Radio", are located on Back Road in Ocracoke.[55]

The Ocracoke Observer newspaper provides coverage of local and regional events. The Observer website is updated daily and a monthly print edition is produced March through December.[56]

Ocracoke is the first setting of the protagonists in the book, "Sink Or Swim: A Novel of WWII" by Steve Watkins.

Ocracoke appears in the novel "A Breath of Snow and Ashes" by Diana Gabaldon.

References

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Talk Like a Tarheel Archived 2013-06-22 at the Wayback Machine, from the North Carolina Collection website at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 2013-01-29.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001): Ocracoke CDP, North Carolina". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- "Ocracoke's Most Famous Visitor". nps.gov. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- "Blackbeard the Pirate". ocracokeweb.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-19. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- "Ocracoke Island, North Carolina: A Research Guide". University of North Carolina Library. Archived from the original on 2013-08-27. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- Konstam, Angus (2006). Blackbeard: America's Most Notorious Pirate. John Wiley & Sons. p. 336. ISBN 0-471-75885-X.

- John Amrhein. "Ocracoke, North Carolina". treasureislandtheuntoldstory.com. Retrieved 2013-06-02.

- "N.C. 12 on Ocracoke Island to Open to All Traffic Thursday". NCDOT. 2019-04-12. Retrieved 2020-03-01.

- The inlet appears as "Okok" in the map "A New Description of Carolina" engraved by Francis Lamb (London, Tho. Basset and Richard Chiswell, 1676).

- "The History Behind Ocracoke Island". ocracokepreservation.org. Archived from the original on 2014-10-09. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- Earl W. O'Neal, Jr. "OCRACOKE ISLAND HISTORY - Hyde County, NC". files.usgwarchives.net (USGenWeb Archives). Archived from the original on 2014-08-10. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- "A Brief History of Ocracoke". outerbankschamber.com. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- Cosco, Joseph (28 November 1993). "Blackbeard's Lair". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 6 November 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- D. Moore. (1997) "A General History of Blackbeard the Pirate, the Queen Anne's Revenge and the Adventure". In Tributaries, Volume VII, 1997. pp. 31–35. (North Carolina Maritime History Council)

- Porter, Darwin; Prince, Danforth (2007). Frommers: The Carolinas & Georgia.

- Zacharias, Lee (2015-04-29). "A Circle, A Line, An Island: Ocracoke Ghosts". Our State. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- "Ocracoke Newsletter: September 21, 2011". villagecraftsmen.com. 2011-09-21. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

- "Ocracoke's Favorite Residents". nps.gov. Retrieved 2013-06-02.

- Cindy Price (2005-11-11). "Ocracoke in Fall: Gloriously Empty". nytimes.com. Retrieved 2013-06-03.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Burlingame, Dr. William V. "Hurricane Boards". Ocracoke Newsletter. Village Craftsman. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- "Fort Ocracoke". Ocracoke Navigator. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- "Fort Ocracoke". SIDCO. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- http://www.digital.ncdcr.gov/cdm/ref/collection/p249901coll22/id/20315

- "Outer Banks Ferries". outer-banks.com. Archived from the original on 2013-06-23. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- "TripAdvisor: Ocracoke Traveler Article: Ocracoke: A Primer for the Ocracoke Ferries". tripadvisor.com. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- "Ocracoke History". ocracokeguide.com. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- "Ocracoke Island / Hyde County's Outer Banks". ocracoke-nc.com. Archived from the original on 2014-08-11. Retrieved 2013-06-02.

- "Walking Tour". www.ocracokeisland.com.

- Neala Schwartzberg. "Offbeat Travel". offbeattravel.com. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- Ltd, Copyright Global Sea Temperatures-A.-Connect. "Outer Banks (NC) Water Temperature | United States | Sea Temperatures". World Sea Temperatures. Retrieved 2020-07-26.

- Team, National Weather Service Corporate Image Web. "National Weather Service Climate". w2.weather.gov. Retrieved 2020-07-26.

- "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- "NC Ocracoke". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- "PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University". Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- "The official Ocracoke Civic & Business Tourism Site". ocracokevillage.com. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- "Roxy's Rocks!". OcracokeCurrent. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- "The Official Website of the Ocracoke's Working Watermen's Association". ocracokewatermen.org. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- Robert J. Goldstein (1 January 2000). Coastal Fishing in the Carolinas: From Surf, Pier, and Jetty. John F. Blair, Publisher. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-0-89587-195-4.

- "About Ocracoke Island". ocracokeislandrealty.com. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- "Ocracoke History". ocracoke-nc.com. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- Neal Hutcheson, director (2009). The Carolina Brogue (television documentary). Ocracoke Island, North Carolina. Archived from the original on 2017-09-12. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- Wolfram & Schilling-Estes (1997:123)

- Wolfram, Walt; Estes, Natalie Schilling (1997). Hoi Toide on the Outer Banks. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 117–136. ISBN 0-8078-4626-0.

- "Profile: Ocracoke, North Carolina". city-data.com. Retrieved 2013-06-02.

- "Ocracoke, North Carolina Population: Census 2010 and 2000 Interactive Map, Demographics, Statistics, Quick Facts". censusviewer.com. Retrieved 2013-06-02.

- "Search for Public Schools - School Detail for Ocracoke School". nces.ed.gov. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "Ocracoke Island (W95)". ocracokeairport.com. 2013-06-01. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- "History of the Ocracoke Volunteer Fire Department". ocracokevfd.org. Archived from the original on 2014-08-10. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- Weigl, Andrea (September 1, 2015). "Learning to make a better fig cake". The News & Observer. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- "WOVV Facility Record". Federal Communications Commission, audio division. Retrieved September 18, 2018.

- "Contact Us - WOVV Radio". Ocracoke Foundation. Retrieved September 18, 2018.

- "The Ocracoke Observer". Ocracoke Observer. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Ocracoke. |

- Ocracoke village website

- Cape Hatteras National Seashore - Ocracoke Island

- Clips from The Ocracoke Brogue documentary

- Preliminary Site Sketch, Fort Ocracoke

| Preceded by Hatteras Inlet Peninsula |

Beaches of The Outer Banks | Succeeded by Portsmouth Island |