Wright Brothers National Memorial

Wright Brothers National Memorial, located in Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, commemorates the first successful, sustained, powered flights in a heavier-than-air machine. From 1900 to 1903, Wilbur and Orville Wright came here from Dayton, Ohio, based on information from the U.S. Weather Bureau about the area's steady winds. They also valued the privacy provided by this location, which in the early twentieth century was remote from major population centers.

| Wright Brothers National Memorial | |

|---|---|

Monument at Wright Brothers National Memorial. | |

| |

| Location | Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, USA |

| Coordinates | 36.0143°N 75.6679°W |

| Area | 428 acres (173 ha)[1] |

| Authorized | March 2, 1927 |

| Visitors | 445,455 (in 2011)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Wright Brothers National Memorial |

| |

| Official name | Wright Brothers National Memorial Visitor Center |

| Designated | January 3, 2001[3] |

| Designated | October 15, 1966 |

| Reference no. | 66000071[4] |

| Architects | Rogers & Poor; National Park Service |

| Architecture | Art Deco |

Administrative history

Authorized as Kill Devil Hill Monument on March 2, 1927, it was transferred from the War Department to the National Park Service on August 10, 1933. Congress renamed it and designated it a national memorial on December 4, 1953. As with all historic areas administered by the National Park Service, the national memorial was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966. The memorial's visitor center, designed by Ehrman Mitchell and Romaldo Giurgola, was designated a National Historic Landmark on January 3, 2001.[3] The memorial is co-managed with two other Outer Banks parks, Fort Raleigh National Historic Site and Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

Exhibits and features

The field and hangar

The Wrights made four flights from level ground near the base of the hill on December 17, 1903, in the Wright Flyer, following three years of gliding experiments from atop this and other nearby sand dunes. It is possible to walk along the actual routes of the four flights, with small monuments marking their starts and finishes. Two wooden sheds, based on historic photographs, recreate the world's first airplane hangar and the brothers' living quarters.

Visitor Center

The Visitor Center is home to a museum featuring models and actual tools and machines used by the Wright brothers during their flight experiments including a reproduction of the wind tunnel used to test wing shapes and a portion of the engine used in the first flight. In one wing of the Visitor Center is a life-size replica of the Wright brothers' 1903 Wright Flyer, the first powered heavier-than-air aircraft in history to achieve controlled flight (the original being displayed at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C.). A full-scale model of the Brothers' 1902 glider is also present, having been constructed under the direction of Orville Wright himself. Adorning the walls of the glider room are portraits and photographs of other flight pioneers throughout history.

The visitor center's Modern design was a departure from the National Park Service's earlier, more traditional buildings, and was built as part of its "Mission 66" modernization and expansion program. As the first major building of that effort, it was a high-profile success, bringing critical notice for its Modern design and launching the careers of its designers. It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1975 for its architecture and its importance to the Park Service's program.[5]

Kill Devil Hill and the Memorial Tower

A 60 feet (18.29 m) granite monument, dedicated in 1932, is perched atop 90-foot-tall (27 m) Kill Devil Hill, commemorating the achievement of the Wright brothers. They conducted many of their glider tests on the massive shifting dune that was later stabilized to form Kill Devil Hill. Inscribed in capital letters along the base of the memorial tower is the phrase "In commemoration of the conquest of the air by the brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright conceived by genius achieved by dauntless resolution and unconquerable faith." Atop the tower is a marine beacon, similar to one found in a lighthouse.[6]

The doors of the tower are stainless steel over nickel, with a price of $3,000 in 1928 (equivalent to $35,818 in 2019[7]). The six relief panels represent the conquest of the air:

Left Door (top to bottom): The contraptions of the French locksmith Besnier, who thought he could fly if he propelled himself into the air while wearing paddles on his arms and legs; An homage to Otto Lilienthal, a German who died while conducting gliding experiments; A reference to a French philosopher who thought that since dew rose in the morning, if it could be placed in an expandable bag attached to a box and sail, it would naturally rise when placed in the sun. (It didn't.)

Right Door (top to bottom): Icarus, the Greek mythological figure who tried to fly from Crete by attaching feathers to his arms with wax. He fell when he flew too close to the sun, melting the wax; Bird flight to plane flight, or the rise of a phoenix; Kites used by the Wrights and others in early experiments

Building the Memorial

The tower was designed by Rodgers and Poor, a New York City architectural firm; the design was officially selected on February 14, 1930. Prior to the memorial's construction, the War Department selected Captain William H. Kindervater of the Quartermaster Corps to prepare the site for construction and to manage the area landscaping. To secure the sandy foundation, Captain Kindervater selected bermuda grass to be planted on Kill Devil Hill and the surrounding area. He also ordered a special fertilizer to be spread throughout the area to promote grass and shrubbery growth and decided to build a fence to prevent animal grazing. With a strong foundation in place, the Office of the Quartermaster selected Marine Captain John A. Gilman to preside over the construction project. Construction began in October 1931 and with a budget of $213,000 (equivalent to $2.94 million in 2019[7]), the memorial was completed in November 1932. In the end, 1,200 tons (1.1 million kg) of granite, more than 2,000 tons (1.8 million kg) of gravel, more than 800 tons (730,000 kg) of sand and almost 400 tons (360,000 kg) of cement were used to build the structure, along with numerous other materials. It is constructed of granite mined at the North Carolina Granite Corporation Quarry Complex.[8]

Memorial dedication

November 14, 1932, was selected as the dedication day. Over 20,000 people were expected to attend the event, but only around 1,000 showed up on a stormy and windy day. Orville Wright was the main guest of honor at the ceremony, and aviator Ruth Nichols was given the privilege of removing the American flag that covered the word "GENIUS" and the plaque on the monument. President Herbert Hoover was unable to attend the ceremony,[9] but a letter from the President was read prior to the dedication. The ceremony also marked the rare occasion when one of the persons the memorial was dedicated to (Orville Wright) was still living.

The hill offers great views of the surrounding area.

Repairs

In 2008, the memorial, long plagued by seepage problems, was refurbished and better water control measures were installed. Interior lighting was improved and a steel map of early aviation flights restored. Visitors occasionally may ascend the tower by reservation.[10]

Centennial of Flight

On December 17, 2003, the Centennial of Flight was celebrated at the Park. The ceremony was hosted by flight enthusiast John Travolta, and included appearances by President George W. Bush, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, and test pilot Chuck Yeager. The Centennial Pavilion was built for the celebration and housed exhibits showing the Outer Banks at the turn-of-the-century, the development of the 1903 replica, and NASA provided displays on aviation and flight.[11] The Centennial Pavilion closed in 2014 and is slated to be demolished due to budget constraints.[12]

An interactive sculpture was donated by the State of North Carolina and dedicated during the celebration. The life sized sculpture, created by Stephen H. Smith, is a full-sized replica of the 1903 Wright Flyer the moment the flight began and includes the Wright Brothers along with members of the Kill Devil Hills Life-Saving Station who assisted in moving the aircraft, as well as John T. Daniels who took the now famous photograph of the first flight.[13]

Curiously the sculpture correctly has a criss-crossed chain driving the port propeller but incorrectly has this propeller being identical to, rather than a mirror image of, the starboard propeller.[14]

Gallery

Kill Devil Hill Monument, as it appeared in 1929.

Kill Devil Hill Monument, as it appeared in 1929. Photo of the monument from the rear.

Photo of the monument from the rear. Overview of the site taken from the memorial atop Kill Devil Hill.

Overview of the site taken from the memorial atop Kill Devil Hill. Reproduction of the launch rail

Reproduction of the launch rail First landing spot

First landing spot In 2001, the US Mint selected the first flight as the image North Carolina's issue in the state quarter series

In 2001, the US Mint selected the first flight as the image North Carolina's issue in the state quarter series Sign by the National Park Service

Sign by the National Park Service The first powered flight site from the east. The monument in the center was established in 1928.

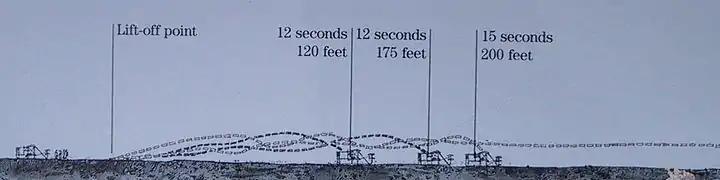

The first powered flight site from the east. The monument in the center was established in 1928. Flight profile from the east

Flight profile from the east Big Kill Devil Hill

Big Kill Devil Hill Pieces of fabric and wood from the Wright Flyer traveled to the Moon in the Apollo 11 lunar module Eagle

Pieces of fabric and wood from the Wright Flyer traveled to the Moon in the Apollo 11 lunar module Eagle

See also

References

- "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- "Wright Brothers National Memorial Visitor Center". National Historic Landmarks Program. Archived from the original on May 10, 2015. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- "National Register Information System – Wright Brothers National Memorial (#66000071)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. November 2, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- "NHL nomination for Wright Brothers National Memorial Visitors Center" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- "Monument To Open Following Restoration Provided By First Flight Foundation" (Press release). National Park Service. June 17, 2008. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2020). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved September 22, 2020. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- Parham, David W.; Sumner, Jim (November 1979). "North Carolina Granite Corporation Quarry Complex" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places - Nomination and Inventory. North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- Chapman, William R.; Hanson, Jill K. (January 1997). "The Wright Brothers National Memorial: The Memorial Tower". National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 21, 2006. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- Kozak, Catherine (June 26, 2008). "Restored Wright brothers memorial makes its debut". The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- "Places to Go: Wright Brothers Monument". National Park Service. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- Walker, Sam (November 27, 2013). "Centennial Pavilion will come down under budget constraints". The Outer Banks Voice. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- "Wright brothers take flight in sculpture". USA Today. December 13, 2003. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- "Propeller Propulsion". NASA. March 29, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wright Brothers National Memorial. |

- Official website

- "Wright Brothers National Memorial". National Park Service. April 18, 2005. Archived from the original on December 14, 2010.

- "Aviation: From Sand Dunes to Sonic Booms". National Register of Historic Places. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015.

- "Video: The Wright Brothers Monument". RTP TV. 2003.

- Wright, Hamilton M. (July 1930). "Chaining a Mountain of Sand". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. pp. 99–100. ISSN 0032-4558.

- "PC Modders Latest Design Homage to Wright Brothers Monument". Intel Free Press. August 23, 2013. Archived from the original on January 11, 2017.

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. NC-396, "Wright Brothers National Memorial Visitor Center, Highway 158, Kill Devil Hills, Dare County, NC", 41 photos, 2 color transparencies, 7 photo caption pages