Oldest Dryas

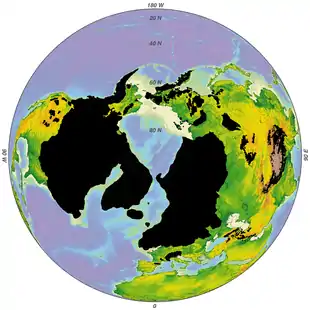

The Oldest Dryas[lower-alpha 1] is a biostratigraphic subdivision layer corresponding to an abrupt cooling event, or stadial, which occurred during the last glacial retreat.[1][2] The time period to which the layer corresponds varies between regions, but it is generally dated as starting at 18.5-17 ka BP and ending 15-14 ka BP.[3][4][5][6][7] As with the Younger and Older Dryas events, the stratigraphic layer is marked by abundance of the pollen and other remains of Dryas octopetala, an indicator species that colonizes arctic-alpine regions.

In the Alps, the Oldest Dryas corresponds to the Gschnitz stadial of the Würm glaciation. The term was originally defined specifically for terrestrial records in the region of Scandinavia, but has come to be used both for ice core stratigraphy in areas across the world, and to refer to the time period itself and its associated temporary reversal of the glacial retreat.[1]

In archaeological chronology, the Older Dryas falls within the period of the Upper Palaeolithic; Europe was then occupied by Magdalenian hunter gatherers.[8]

Flora

During the Oldest Dryas, Europe was treeless and similar to the Arctic tundra, but much drier and grassier than the modern tundra. It contained shrubs and herbaceous plants such as the following:

- Poaceae, grasses

- Artemisia

- Betula nana, dwarf birch

- Salix retusa, dwarf willow

- Dryas octopetala

Grassland (Inner Mongolia)

Grassland (Inner Mongolia) Artemisia vulgaris

Artemisia vulgaris Betula nana

Betula nana Dryas octopetala

Dryas octopetala

Fauna

Species were mainly Arctic but during the Glacial Maximum, the warmer weather species had withdrawn into refugia and began to repopulate Europe in the Oldest Dryas.

The brown bear, Ursos arctos, was among the first to arrive in the north. Genetic studies indicate North European brown bears came from a refugium in the Carpathians of Moldavia. Other refugia were in Italy, Spain and Greece.

The bears would not have returned north except in pursuit of food. The tundra must already have been well populated. It is likely that the species hunted by humans at Lake Neuchâtel in Switzerland by the end of the period were present during it. Here are other animals present:

- Gavia arctica, black-throated diver

- Podiceps nigricollis, black-necked grebe

- Cygnus cygnus, whooper swan

- Aquila chrysaetos, golden eagle

Gavia arctica

Gavia arctica Podiceps nigricollis

Podiceps nigricollis Cygnus cygnus

Cygnus cygnus Aquila chrysaetos

Aquila chrysaetos

The above birds are primarily maritime. They must have fed in the copious glacial waters of the north that were just beginning to be released.

- Lota lota, burbot

- Thymallus thymallus, grayling

- Rutilus rutilus, roach

- Salmo trutta, trout

- Salvelinus alpinus, char

Glacial stream

Glacial stream Lota lota

Lota lota Salmo trutta

Salmo trutta Salvelinus

Salvelinus

The smaller mammals of the food chain inhabited the herbaceous blanket of the tundra:

- Discrotonyx torquatus, collared lemming

- Microtus oeconomus, root vole

- Microtus arvalis, common vole

- Chionmys nivalis, snowy vole

- Lepus timidus, Arctic hare

- Marmota marmota, marmot

Microtus oeconomus

Microtus oeconomus Microtus arvalis

Microtus arvalis Lepus timidus

Lepus timidus Marmota marmota

Marmota marmota

In addition to bears and birds were other predators of the following small animals:

- Felis lynx, lynx

- Alopex lagopus, Arctic fox

- Canis lupus, wolf

Lynx (or Felis) lynx

Lynx (or Felis) lynx Alopex lagopus

Alopex lagopus Canis lupus

Canis lupus Icelandic horse, perhaps like Equus ferus

Icelandic horse, perhaps like Equus ferus

Humans were interested in the large mammals, which included:

- Rangifer tarandus, reindeer

- Equus ferus, wild horse

- Capra ibex, ibex

At some point, the larger mammals arrived: hyena, woolly rhinoceros, cave bear and mammoth.

Rangifer tarandus

Rangifer tarandus Capra ibex

Capra ibex Woolly rhinoceros

Woolly rhinoceros Mammoth

Mammoth

See also

Notes

- The standard sequence between about 18,500 and 11,700 years ago is Oldest Dryas (cold), then Bølling oscillation (warming), then Older Dryas (cold), then Allerød oscillation (warming), then Younger Dryas (cold). A few experts (confusingly) use the terms Old or Older instead of Oldest and Middle or Medium instead of Older.

References

- Rasmussen, Sune O.; Bigler, Matthias; Blockley, Simon P.; Blunier, Thomas; Buchardt, Susanne L.; Clausen, Henrik B.; Cvijanovic, Ivana; Dahl-Jensen, Dorthe; Johnsen, Sigfus J.; Fischer, Hubertus; Gkinis, Vasileios; Guillevic, Myriam; Hoek, Wim Z.; Lowe, J. John; Pedro, Joel B.; Popp, Trevor; Seierstad, Inger K.; Steffensen, Jørgen Peder; Svensson, Anders M.; Vallelonga, Paul; Vinther, Bo M.; Walker, Mike J.C.; Wheatley, Joe J.; Winstrup, Mai (December 2014). "A stratigraphic framework for abrupt climatic changes during the Last Glacial period based on three synchronized Greenland ice-core records: refining and extending the INTIMATE event stratigraphy". Quaternary Science Reviews. 106: 14–28. Bibcode:2014QSRv..106...14R. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.09.007.

- Hoek, Wim (2009). "Bølling-Allerød Interstadial". In Gornitz, Vivien (ed.). Encyclopedia of Paleoclimatology and Ancient Environments. Dordrecht: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-4551-6.

- Carlson, Anders E.; Winsor, Kelsey (26 August 2012). "Northern Hemisphere ice-sheet responses to past climate warming" (PDF). Nature Geoscience. 5 (9): 607–613. Bibcode:2012NatGe...5..607C. doi:10.1038/NGEO1528. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- Clark, P. U.; Shakun, J. D.; Baker, P. A.; Bartlein, P. J.; Brewer, S.; Brook, E.; Carlson, A. E.; Cheng, H.; Kaufman, D. S.; Liu, Z.; Marchitto, T. M.; Mix, A. C.; Morrill, C.; Otto-Bliesner, B. L.; Pahnke, K.; Russell, J. M.; Whitlock, C.; Adkins, J. F.; Blois, J. L.; Clark, J.; Colman, S. M.; Curry, W. B.; Flower, B. P.; He, F.; Johnson, T. C.; Lynch-Stieglitz, J.; Markgraf, V.; McManus, J.; Mitrovica, J. X.; Moreno, P. I.; Williams, J. W. (13 February 2012). "Global climate evolution during the last deglaciation" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (19): E1134–E1142. doi:10.1073/pnas.1116619109. PMC 3358890. PMID 22331892. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- Roberts, Neil (2014). The holocene : an environmental history (3rd ed.). Oxford: John Wiley & sons, Ltd. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-4051-5521-2.

- Shakun, Jeremy D.; Carlson, Anders E. (July 2010). "A global perspective on Last Glacial Maximum to Holocene climate change" (PDF). Quaternary Science Reviews. 29 (15–16): 1801–1816. Bibcode:2010QSRv...29.1801S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.03.016. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- Zheng, Yanhong; Pancost, Richard D.; Liu, Xiaodong; Wang, Zhangzhang; Naafs, B.D.A.; Xie, Xiaoxun; Liu, Zhao; Yu, Xuefeng; Yang, Huan (2 October 2017). "Atmospheric connections with the North Atlantic enhanced the deglacial warming in northeast China". Geology. 45 (11): 1031–1034. Bibcode:2017Geo....45.1031Z. doi:10.1130/G39401.1.

- Wood, Bernard, ed. (2013). "Magdalenian". Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Evolution. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 477. ISBN 978-1-1186-5099-8.

Further reading

- Ehlers, Gibbard, Hughes (eds) (2011) Quaternary Glaciations - Extent and Chronology: A Closer Look Elsevier ISBN 9780444534477

- Bradley, Raymond S. (2013) Paleoclimatology: Reconstructing Climates of the Quaternary Academic Press ISBN 9780123869951