Leporidae

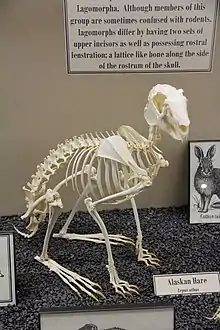

Leporidae is the family of rabbits and hares, containing over 60 species of extant mammals in all. The Latin word Leporidae means "those that resemble lepus" (hare). Together with the pikas, the Leporidae constitute the mammalian order Lagomorpha. Leporidae differ from pikas in that they have short, furry tails and elongated ears and hind legs.

| Rabbits and hares[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Arctic hare (Lepus arcticus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Lagomorpha |

| Family: | Leporidae Fischer de Waldheim, 1817 |

| Genera | |

|

Pentalagus | |

The common name "rabbit" usually applies to all genera in the family except Lepus, while members of Lepus (almost half the species) usually are called hares. Like most common names however, the distinction does not match current taxonomy completely; jackrabbits are members of Lepus, and members of the genera Pronolagus and Caprolagus sometimes are called hares.

Various countries across all continents except Antarctica and Australia have indigenous species of Leporidae. Furthermore, rabbits, most significantly the European rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus, also have been introduced to most of Oceania and to many other islands, where they pose serious ecological and commercial threats.

Characteristics

Leporids are small to moderately sized mammals, adapted for rapid movement. They have long hind legs, with four toes on each foot, and shorter fore legs, with five toes each. The soles of their feet are hairy, to improve grip while running, and they have strong claws on all of their toes. Leporids also have distinctive, elongated and mobile ears, and they have an excellent sense of hearing. Their eyes are large, and their night vision is good, reflecting their primarily nocturnal or crepuscular mode of living.[2]

Leporids range in size from the pygmy rabbit (Brachylagus idahoensis), with a head and body length of 25–29 cm, and a weight of around 300 grams, to the European hare (Lepus europaeus), which is 50–76 cm in head-body length, and weighs from 2.5 to 5 kilograms. Female leporids are almost always larger than males, which is unusual among terrestrial mammals, in which males are usually the larger sex.[3]

Both rabbits and hares are almost exclusively herbivorous (with exceptions among the members of Lepus),[4][5] feeding primarily on grasses and herbs, although they also eat leaves, fruit, and seeds of various kinds. They are coprophagous, as they pass food through their digestive systems twice, first expelling it as soft green feces, called cecotropes, which they then reingest, eventually producing hard, dark fecal pellets. Like rodents, they have powerful front incisor teeth, but they also have a smaller second pair of incisors to either side of the main teeth in the upper jaw, and the structure is different from that of rodent incisors. Also like rodents, leporids lack any canine teeth, but they do have more cheek teeth than rodents do. Their jaws also contain a large diastema. The dental formula of most, though not all, leporids is: 2.0.3.31.0.2.3

They have adapted to a remarkable range of habitats, from desert to tundra, forests, mountains, and swampland. Rabbits generally dig permanent burrows for shelter, the exact form of which varies between species. In contrast, hares rarely dig shelters of any kind, and their bodies are more suited to fast running than to burrowing.[2]

The gestation period in leporids varies from around 28 to 50 days, and is generally longer in the hares. This is in part because young hares, or leverets, are born fully developed, with fur and open eyes, while rabbit kits are naked and blind at birth, having the security of the burrow to protect them.[2] Leporids can have several litters a year, which can cause their population to expand dramatically in a short time when resources are plentiful.

Reproduction

Leporids are typically polygynandrous, and have highly developed social systems. Their social hierarchies determine which males mate when the females go into estrus, which happens throughout the year. Gestation periods are variable, but in general, higher latitudes correspond to shorter gestation periods.[6] Moreover, the gestation time and litter size correspond to predation rates as well. Species nesting below ground tend to have lower predation rates and have larger litters.[7]

Evolution

The oldest known leporid species date from the late Eocene, by which time the family was already present in both North America and Asia. Over the course of their evolution, this group has become increasingly adapted to lives of fast running and leaping. For example, Palaeolagus, an extinct rabbit from the Oligocene of North America, had shorter hind legs than modern forms (indicating it ran rather than hopped) though it was in most other respects quite rabbit-like.[8] Two as yet unnamed fossil finds—dated ~48 Ma (from China) and ~53 Ma (India)—while primitive, display the characteristic leporid ankle, thus pushing the divergence of Ochotonidae and Leporidae yet further into the past.[9]

The cladogram is from Matthee et al., 2004, based on nuclear and mitochondrial gene analysis.[10]

| Leporidae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Classification

Family Leporidae:[1] rabbits and hares

- Genus Pentalagus

- Amami rabbit/Ryūkyū rabbit, Pentalagus furnessi

- Genus Bunolagus

- Riverine rabbit, Bunolagus monticularis

- Genus Nesolagus

- Sumatran striped rabbit, Nesolagus netscheri

- Annamite striped rabbit, Nesolagus timminsi

- Genus Romerolagus

- Volcano rabbit, Romerolagus diazi

- Genus Brachylagus

- Pygmy rabbit, Brachylagus idahoensis

- Genus Sylvilagus

- Subgenus Tapeti

- Swamp rabbit, Sylvilagus aquaticus

- Tapeti, Sylvilagus brasiliensis

- Dice's cottontail, Sylvilagus dicei

- Omilteme cottontail, Sylvilagus insonus

- Marsh rabbit, Sylvilagus palustris

- Venezuelan lowland rabbit, Sylvilagus varynaensis

- Subgenus Sylvilagus

- Desert cottontail, Sylvilagus audubonii

- Manzano mountain cottontail, Sylvilagus cognatus

- Mexican cottontail, Sylvilagus cunicularis

- Eastern cottontail, Sylvilagus floridanus

- Tres Marias rabbit, Sylvilagus graysoni

- Mountain cottontail, Sylvilagus nuttallii

- Appalachian cottontail, Sylvilagus obscurus

- Robust cottontail, Sylvilagus robustus

- New England cottontail, Sylvilagus transitionalis

- Subgenus Microlagus

- Brush rabbit, Sylvilagus bachmani

- San Jose brush rabbit, Sylvilagus mansuetus

- Subgenus Tapeti

- Genus Oryctolagus

- European rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus

- Genus Poelagus

- Bunyoro rabbit, Poelagus marjorita

- Genus Pronolagus

- Natal red rock hare, Pronolagus crassicaudatus

- Jameson's red rock hare, Pronolagus randensis

- Smith's red rock hare, Pronolagus rupestris

- Hewitt's red rock hare, Pronolagus saundersiae

- Genus Caprolagus

- Hispid hare, Caprolagus hispidus

- Genus Lepus

- Subgenus Macrotolagus

- Antelope jackrabbit, Lepus alleni

- Subgenus Poecilolagus

- Snowshoe hare, Lepus americanus

- Subgenus Lepus

- Arctic hare, Lepus arcticus

- Alaskan hare, Lepus othus

- Mountain hare, Lepus timidus

- Subgenus Proeulagus

- Black-tailed jackrabbit, Lepus californicus

- White-sided jackrabbit, Lepus callotis

- Cape hare, Lepus capensis

- Tehuantepec jackrabbit, Lepus flavigularis

- Black jackrabbit, Lepus insularis

- Scrub hare, Lepus saxatilis

- Desert hare, Lepus tibetanus

- Tolai hare, Lepus tolai

- Subgenus Eulagos

- Broom hare, Lepus castrovieoi

- Yunnan hare, Lepus comus

- Korean hare, Lepus coreanus

- Corsican hare, Lepus corsicanus

- European hare, Lepus europaeus

- Granada hare, Lepus granatensis

- Manchurian hare, Lepus mandschuricus

- Woolly hare, Lepus oiostolus

- Ethiopian highland hare, Lepus starcki

- White-tailed jackrabbit, Lepus townsendii

- Subgenus Sabanalagus

- Ethiopian hare, Lepus fagani

- African savanna hare, Lepus microtis

- Subgenus Indolagus

- Hainan hare, Lepus hainanus

- Indian hare, Lepus nigricollis

- Burmese hare, Lepus peguensis

- Subgenus Sinolagus

- Chinese hare, Lepus sinensis

- Subgenus Tarimolagus

- Yarkand hare, Lepus yarkandensis

- Subgenus incertae sedis

- Japanese hare, Lepus brachyurus

- Abyssinian hare, Lepus habessinicus

- Subgenus Macrotolagus

- Genus †Serengetilagus

- †Serengetilagus praecapensis

- Genus †Aztlanolagus

- †Aztlanolagus agilis

Predation

Predators of rabbits and hares include raccoons, snakes, eagles, canids, cats, mustelids, owls and hawks. Animals that eat roadkill rabbits include vultures and buzzards.

See also

References

- Hoffman, R.S.; Smith, A.T. (2005). "Order Lagomorpha". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 194–211. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Chapman, J.; Schneider, E. (1984). MacDonald, D. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. pp. 714–719. ISBN 978-0-87196-871-5.

- Ralls, Katherine (June 1976). "Mammals in Which Females are Larger Than Males". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 51 (2): 245–276. doi:10.1086/409310.

- Best, Troy L.; Henry, Travis Hill (1994). "Lepus arcticus". Mammalian Species. American Society of Mammalogists (published 2 June 1994) (457): 1–9. doi:10.2307/3504088. JSTOR 3504088. OCLC 46381503.

- "Snowshoe Hare". eNature: FieldGuides. eNature.com. 2007. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- Chapman, Joseph A. (1 September 1984). "Latitude and Gestation Period in New World Rabbits (Leporidae: Sylvilagus and Romerolagus)". The American Naturalist. 124 (3): 442–445. doi:10.1086/284286. JSTOR 2461471.

- Virgós, Emilio; Cabezas-Díaz, Sara; Blanco-Aguiar, José Antonio (1 August 2006). "Evolution of life history traits in Leporidae: a test of nest predation and seasonality hypotheses". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 88 (4): 603–610. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2006.00646.x. ISSN 1095-8312.

- Savage, R.J.G.; Long, M.R. (1986). Mammal Evolution: an illustrated guide. New York: Facts on File. pp. 128–129. ISBN 978-0-8160-1194-0.

- Handwerk, Brian (21 March 2008). "Easter Surprise: World's Oldest Rabbit Bones Found". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society.

- Matthee, Conrad A.; et al. (2004). "A Molecular Supermatrix of the Rabbits and Hares (Leporidae) Allows for the Identification of Five Intercontinental Exchanges During the Miocene". Systematic Biology. 53 (3): 433–477. doi:10.1080/10635150490445715.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leporidae. |

_(Sylvilagus_palustris).jpg.webp)