Omotic languages

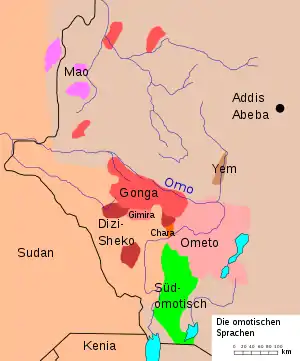

The Omotic languages are a group of languages spoken in southwestern Ethiopia. The Ge'ez script is used to write some of the Omotic languages, the Latin script for some others. They are fairly agglutinative and have complex tonal systems (for example, the Bench language). The languages have around 6.2 million speakers. The group is generally classified as belonging to the Afroasiatic language family, but this is disputed by some.

| Omotic | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Ethiopia | ||

| Linguistic classification | Afro-Asiatic

| ||

| Subdivisions | |||

| ISO 639-5 | omv | ||

| Glottolog | None | ||

Omotic languages: Neighboring languages:

| |||

Four separate "Omotic" groups are accepted by Glottolog 4.0 and Güldemann (2018): Ta-Ne-Omotic, Dizoid (Maji), Mao, and Aroid ("South Omotic").[1]

Languages

The North and South Omotic branches ("Nomotic" and "Somotic") are universally recognized, with some dispute as to the composition of North Omotic. The primary debate is over the placement of the Mao languages. Bender (2000) classifies Omotic languages as follows:

- South Omotic / Aroid (Hamer-Banna, Aari, Dime, Karo)

- North Omotic / Non-Aroid

Apart from terminology, this differs from Fleming (1976) in including the Mao languages, whose affiliation had originally been controversial, and in abolishing the "Gimojan" group. There are also differences in the subclassification of Ometo, which is not covered here.

Hayward (2003)

Hayward (2003) separates out the Mao languages as a third branch of Omotic and breaks up Ometo–Gimira:

Classification

Omotic is generally considered the most divergent branch of the Afroasiatic languages. Greenberg (1963) had classified it as the Western branch of Cushitic. Fleming (1969) argued that it should instead be classified as an independent branch of Afroasiatic, a view which Bender (1971) established to most linguists' satisfaction,[3] though a few linguists maintain the West Cushitic position[4] or that only South Omotic forms a separate branch, with North Omotic remaining part of Cushitic. Blench (2006) notes that Omotic shares honey-related vocabulary with the rest of Afroasiatic but not cattle-related vocabulary, suggesting that the split occurred before the advent of pastoralism. A few scholars have raised doubts that the Omotic languages are part of the Afroasiatic language family at all,[5][6] and Theil (2006) proposes that Omotic be treated as an independent family.[7] However, the general consensus, based primarily on morphological evidence, is that membership in Afroasiatic is well established.[8][9][10]

Glottolog

Hammarström, et al. in Glottolog does not consider Omotic to be a unified group, and also does not consider any of the "Omotic" groups to be part of the Afroasiatic phylum. Glottolog accepts the following as independent language families.

- Ta-Ne-Omotic

- Dizoid (Maji)

- Mao

- Aroid (Ari-Banna; "South Omotic")

These four families are also accepted by Güldemann (2018), who similarly doubts the validity of Omotic as a unified group.[1]

Reconstruction

Bender (1987: 33-35)[11] reconstructs the following proto-forms for Proto-Omotic and Proto-North Omotic, the latter which is considered to have descended from Proto-Omotic.

| English gloss | Proto- Omotic | Proto-North Omotic |

|---|---|---|

| ashes | *bend | |

| bird | *kaf | |

| bite | *sats’ | |

| breast | *t’iam | |

| claw | *ts’ugum | |

| die | *hayk’ | |

| dog | *kan | |

| egg | *ɓul | |

| fire | *tam | |

| grass | *maata | |

| hand | *kuc | |

| head | *to- | |

| hear | *si- | |

| mouth | *non- | |

| nose | *si(n)t’ | |

| root | *ts’ab- | |

| snake | *šooš | |

| stand (vb.) | *yek’ | |

| this | *kʰan- | |

| thou (2.SG) | *ne(n) | |

| water | *haats’ | |

| we (1.PL) | *nu(n) | |

| ye (2.PL) | *int- | |

| green | *c’il- | |

| house | *kyet | |

| left | *hadr- | |

| elephant | *daŋgVr | |

| sister, mother | *ind | |

| armpit | *šoɓ- | |

| boat | *gong- | |

| grave | *duuk | |

| vomit | *c’oš- |

Comparative vocabulary

Sample basic vocabulary of 40 Omotic languages from Blažek (2008):[12]

| Language | eye | ear | nose | tooth | tongue | mouth | blood | bone | tree | water | eat | name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basketo | af | waytsi | sints | ačči | B ɪnts'ɨrs | no·na | suuts | mεk'εts | B mɪts | B waːtse | A moy- | B sumsa |

| Dokka | af | waytsi | si·nts | ačči | ɨrs'ɪns | no·na | su·ts | mik'әts | mittse | wa·tsi | m- | suntsa |

| Male | ’aːpi | waizi | sied‘i | ’ači | ’ɪndɪrsi | daŋka | sugutsi | mεgεtsi | mitsi | waːtsi | mo- | sunsi |

| Wolaita | ayf-iya; A ayp'-iya | haytta | sir-iya | acca; A acc'a | int'arsa | doona | suutta; Ch maččamié | mek'etta | mitta | hatta | m- | sunta |

| Kullo | ayp'-iya | haytsa | siid'-iya | acc'a | ins'arsa | doona | sutsa | mek'etsa | barzap'-iya | hatsa | m- | sutta |

| Cancha | ayp'e | hayts | sire | acc‘a | ins‘arsa | doona | suts | mek'etsa | mits | haats | m- | sunts |

| Malo | ’áɸe | hʌ́je | síd'e | ’áčʰә | ’irɪ́nts | dɔ́nʌ | sútsʰ | mεk‘ɨ́ts‘ | mɪ́ts | ’átsә | m- | sʊns |

| Gofa | ayp'e | haytsa | siide | acc'a | intsarsa | doona | sutsa | mek'etta | mitsa | hatse | m- | suntsa |

| Zala | ayfe | (h)aytsa | sid'e | ačča | int'arsa | duna | tsutsa | mitsa | hatsa | maa- | ||

| Gamu | ayp'e | haytsa | siire | acc'a | ins'arsa | doona | suuts | mek'ets | mitsa | hatse | m- | sunts |

| Dache | ayfe | hayts'e | siyd'e | acé | ɪntsεrs | duna | suts | mek'ets | šara | hatse | m- | sunts |

| Dorze | ayp'e | waye | sire | acc'a | ins'arsa | duuna | suts | mek'etsa | mits | haats | m- | sunts |

| Oyda | ápe, ayfe | B haːye | sid'e | ’ač, pl. o·či | iláns | B doːna | suts | mεk'εts | mɪns'a | haytsi | mu’- | suntsu |

| Zayse | ’áaɸε | waayέ | kuŋké | ’acc' | ints'έrε | baadέ | súuts' | mεk'έεte | mits'a | wáats'i | m- | č'úuč'e |

| Zergulla | ’aːɸe | wai | kuŋki | ’ac'e | ’insәre | haː’e | suːts | nεkεtε | mintsa | waːtse | m- | suːns |

| Ganjule | ’áaɸε | waašέ | kuŋkε | gaggo | ints'úrε | baadέ | súuts' | mεk'έtε | mits'i | waats'i | m- | ts'únts'i |

| Gidicho | ’áaɸε | waašέ | kuŋké | gaggo | ints'úrε | baadέ | súuts'i | mεk'εte | míts'i | wáats'i | m- | ts'únts'i |

| Kachama | ’áaɸε | uwaašέ | kuŋkέ | gaggo | ints'úrε | baadέ | súuts'ε | mέk‘έtee | mits'i | wáats'i | m- | ts'únts'i |

| Koyra | ’áɸε | waayέ | siid'ε | gaggo | ’únts'úrε | ’áaša | súuts' | mεk‘έεte | míts'e; Ce akka | wáats'e | múuwa | súuntsi |

| Chara | áːpa | wóːya | sínt'u | áč'a | ’íns'ila | noːná | súːta | mertá | mítsa | áːs'a | ḿ-na | sumá |

| Bench | ap | (h)ay | sint' | gaš; san | eyts' | non | sut | mert | inč | so’ | m’ | sum |

| She | af | ai | sint' | gaš | ets' | non | sut | mεrt | enc | so’ | mma | sum |

| Yemsa | aafa; kema | odo | siya | a’ya | terma | noono | anna | mega | i’o | aka | me | suna |

| Bworo | aawa | waaza | šint'a | gaša | albeera | noona | ts'atts'a | mak'әttsa | mitta | aatsa | maa- | šuutsa |

| Anfillo | aːfo | waːjo | šiːnto | gaːššo | εrɪːtso | nɔːno | ts'antso | šaušo | mɪːtso | yuːro | m | šiːgo |

| Kafa | affo, aho | wammo; kendo | muddo | gašo | eč'iyo | nono; koko | dammo | šawušo | met'o | ač'o | mammo; č‘okko | šiggo |

| Mocha | á·p̱o | wa·mmo | šit'ó | gášo | häč'awo | no·no | damo | ša·wúšo | mit'ó | à·č'o | ma̱·(hä) | šəgo |

| Proto-Omotic[13] | *si(n)t’ | *non- | *haats’ | |||||||||

| Maji | ||||||||||||

| Proto-Maji[14] | *ʔaːb | *háːy | *aːç’u | *eːdu | *uːs | *inču | *haːy | *um | ||||

| Dizi | ab-u | aːi | sin-u | ažu | yabɪl | εd-u | yεrm-u | us | wɪč | aːi | m- | sɪm-u |

| Shako | áːb | aːy | B sɪnt' | áːč'u | érb | eːd | yärm | uːsu | íːnču | áːy | m̥̀- | suːm |

| Nayi | ’aːf | B haːy | si.n | B acu | B yalb | eːdu | yarbm | ’uːs | B incus | B hai | m- | suːm |

| Mao | ||||||||||||

| Mao | áːfέ | wáːlέ | šíːnt'έ | àːts'ὲ | ánts'ílὲ | pɔ́ːnsὲ | hándέ | máːlt‘έ | ’íːntsὲ | hàːtsὲ | hà míjà | jèːškέ |

| Seze | aːb, áːwi | wέὲ | šíːnté | háːts'έ, haːnsì | jántsílὲ/ t'agál | waːndè | hámbìlὲ | bàk‘ílí | ’innsì | háːns'ì | máːmɔ́ | nìːší |

| Hozo | abbi | wεεra | šini | ats'i | S wìntə́lә | waandi | hambilε | bak‘ilε | S ’íːnti | haani | maa | iiši |

| Aroid | ||||||||||||

| Dime | ’afe, ’aɸe | k'aːme | nʊkʊ | F baŋgɪl; ɪts; kәsɪl | ’ɨdәm | ’afe; B ’app- | maχse; F dzumt | k‘oss; F k‘ʊs | ’aχe; B haːɣo | naχe; B nәːɣ- | ’ɨčɨn | mɨze; F naːb |

| Hamer | api, afi | k'a(ː)m- | nuki | ’ats' | ’ad’ab | ap- | zum’i | leːfi | ak'- | noko | kʊm- | nam- |

| Banna | afi | k'ami | nuki | atsi | adʌb/adɪm | afa | zump'i | lεfi | ɑhaka/haːk'a | noko | its-; kum- | na(a)bi |

| Karo | afi | k'ami | nuki | asi | attәp' | M ’apo | mәk'әs | lefi | aka | nuk'o | isidi | |

| Ari | afi | k'ami | nuki | atsi; B kasel geegi | adim | afa | zom’i | lεfi | ahaka | noɣa; B nɔk'ɔ | its- | nami |

| Ubamer | a·fi | ɣ/k'a·mi | nuki | atsi | admi | afa | mək'əs ~ -ɣ- | lεfí | aɣa | luk'a, luɣa | ’its- | na·mi |

| Galila | a·fi | k'a·mi | nuki | ači | admi | afa | mәk'әs | lεfí | aɣa/aháɣa | lu·ɣa/lo·ɣa | ič- | la·mi |

See also

Notes

- Güldemann, Tom (2018). "Historical linguistics and genealogical language classification in Africa". In Güldemann, Tom (ed.). The Languages and Linguistics of Africa. The World of Linguistics series. 11. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 58–444. doi:10.1515/9783110421668-002. ISBN 978-3-11-042606-9.

- Blench, 2006. The Afro-Asiatic Languages: Classification and Reference List

- Hayward (2000:85)

- Lamberti (1991), Zaborksi (1986)

- I. M. Diakonoff (1998) Journal of Semitic Studies 43:209: "It is quite evident that cultural ties between Proto-Semitic and the African branches of the Afrasian macrofamily must have been severed at a very early date indeed. However, the grammatical structure of [Common Semitic] (especially in the verb) is obviously close to that of Common Berbero-Libyan (CBL), as well as to Bedauye. (Bedauye might, quite possibly, be classified as a family distinct from the rest of Kushitic.) The same grammatical isoglosses are somewhat more feebly felt between Semitic and (the other?) Kushitic languages. They practically disappear between the Semitic and the Omotic languages, which were formerly termed Western Kushitic, but which actually may not be Afrasian at all, like their neighbours the Nubian languages and Meroitic."

- Newman (1980)

- Rolf Theil (2006) Is Omotic Afro-Asiatic? pp 1–2: "I claim to show that no convincing arguments have been presented [for the inclusion of Omotic (OM) in Afro-Asiatic (AA)], and that OM should be regarded as an independent language family. No closer genetic relations have been demonstrated between OM and AA than between OM and any other language family."

- Gerrit Dimmendaal (2008) "Language Ecology and Linguistic Diversity on the African Continent", in Language and Linguistics Compass 2/5:841: "Although its Afroasiatic affiliation has been disputed, the allocation of Omotic within this family is now well-established, based on the attestation of morphological properties that this family shares with other Afroasiatic branches."

- Ehret, Christopher (2010-12-17). History and the Testimony of Language. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-94759-7.

- Lecarme, Jacqueline (2003-01-01). Research in Afroasiatic Grammar Two. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-4753-7.

- Bender, Lionel M. 1987. "First Steps Toward proto-Omotic." Current Approaches to African Linguistics 3 (1987): 21-36.

- Blažek, Václav. 2008. A lexicostatistical comparison of Omotic languages. In Bengtson (ed.), 57–148.

- Bender, Lionel M. 1987. "First Steps Toward proto-Omotic." Current Approaches to African Linguistics 3 (1987): 21-36.

- Aklilu, Yilma. 2003. Comparative phonology of the Maji languages. Journal of Ethiopian studies 36: 59-88.

Sources cited

- Bender, M. Lionel. 2000. Comparative Morphology of the Omotic Languages. Munich: LINCOM.

- Fleming, Harold. 1976. Omotic overview. In The Non-Semitic Languages of Ethiopia, ed. by M. Lionel Bender, pp. 299–323. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University.

- Newman, Paul. 1980. The classification of Chadic within Afroasiatic. Universitaire Pers Leiden.

General Omotic bibliography

- Bender, M. L. 1975. Omotic: a new Afroasiatic language family. (University Museum Series, 3.) Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University.

- Blench, Roger. 2006. Archaeology, Language, and the African Past. AltaMira Press

- Hayward, Richard J., ed. 1990. Omotic Language Studies. London: School of Oriental and African Studies.

- Hayward, Richard J. 2003. Omotic: the "empty quarter" of Afroasiatic linguistics. In Research in Afroasiatic Grammar II: selected papers from the fifth conference on Afroasiatic languages, Paris 2000, ed. by Jacqueline Lecarme, pp. 241–261. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Lamberti, Marcello. 1991. Cushitic and its classification. Anthropos 86(4/6):552-561.

- Zaborski, Andrzej. 1986. Can Omotic be reclassified as West Cushitic? In Gideon Goldenberg, ed., Ethiopian Studies: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference pp. 525–530. Rotterdam: Balkema.

External links

- Is Omotic Afro-Asiatic? by Rolf Theil