Somali language

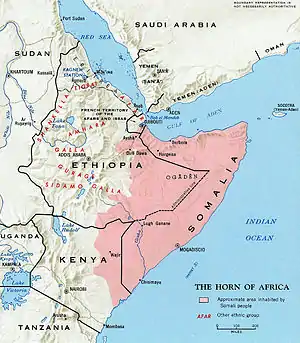

Somali /səˈmɑːli, soʊ-/[4][5] (Latin: Af-Soomaali; Osmanya: 𐒖𐒍 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘 [æ̀f sɔ̀ːmɑ́ːlì])[6] is an Afroasiatic language belonging to the Cushitic branch. It is spoken as a mother tongue by Somalis in Greater Somalia and the Somali diaspora. Somali is an official language of Somalia and Somaliland,[7] a national language in Djibouti, and a working language in the Somali Region of Ethiopia and also in North Eastern Kenya. It is used as an adoptive language by a few neighboring ethnic minority groups and individuals. The Somali language is written officially with the Latin alphabet.

| Somali | |

|---|---|

| Af Soomaali,[1] Soomaali[2] 𐒖𐒍 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘, 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘 | |

| Region | Horn of Africa |

| Ethnicity | Somalis |

Native speakers | 18.63 million (2020)[3] |

| Somali Latin alphabet (Latin script; official) Wadaad writing (Arabic script) Osmanya alphabet Borama alphabet Kaddare alphabet | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Regional Somali Language Academy |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | so |

| ISO 639-2 | som |

| ISO 639-3 | som |

| Glottolog | soma1255 |

| Linguasphere | 14-GAG-a |

Primary Somali Sprachraum | |

Classification

Somali is classified within the Cushitic branch of the Afroasiatic family; specifically, as Lowland East Cushitic along with Afar and Saho.[8] Somali is the best-documented Cushitic language,[9] with academic studies of the language dating back to the late 19th century.[10]

Geographic distribution

Somali is spoken by Somalis in Somalia, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Yemen and by the Somali diaspora. It is also spoken as an adoptive language by a few ethnic minority groups and individuals in these areas.

Somali is the second most widely spoken Cushitic language after Oromo.[11]

As of 2020, there were approximately 18.63 million speakers of Somali, spread in Greater Somalia of which around 7.8 million resided in Somalia.[3] The language is spoken by an estimated 95% of the country's inhabitants,[10] and also by a majority of the population in Djibouti.[9]

Following the start of the Somali Civil War in the early 1990s, the Somali-speaking diaspora increased in size, with newer Somali speech communities forming in parts of the Middle East, North America and Europe.[3]

Official status

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Somalia |

|---|

| Culture |

| People |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Politics |

|

Constitutionally, Somali and Arabic are the two official languages of Somalia.[12] Somali has been an official national language since January 1973, when the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) declared it the Somali Democratic Republic's primary language of administration and education. Somali was thereafter established as the main language of academic instruction in forms 1 through 4, following preparatory work by the government-appointed Somali Language Committee. It later expanded to include all 12 forms in 1979. In 1972, the SRC adopted a Latin orthography as the official national alphabet over several other writing scripts that were then in use. Concurrently, the Italian-language daily newspaper Stella d'Ottobre ("The October Star") was nationalized, renamed to Xiddigta Oktoobar, and began publishing in Somali.[13] The state-run Radio Mogadishu has also broadcast in Somali since 1943.[14] Additionally, the regional public networks the Puntland TV and Radio and Somaliland National TV, as well as Eastern Television Network and Horn Cable Television, among other private broadcasters, air programs in Somali.[15]

Somali is recognized as an official working language in the Somali Region of Ethiopia.[16] Although it is not an official language of Djibouti, it constitutes a major national language there. Somali is used in television and radio broadcasts,[10][17] with the government-operated Radio Djibouti transmitting programs in the language from 1943 onwards.[14]

The Kenya Broadcasting Corporation also broadcasts in the Somali language in its Iftin FM Programmes. Afsoomali is spoken in North Eastern Kenya[18]

The Somali language is regulated by the Regional Somali Language Academy, an intergovernmental institution established in June 2013 in Djibouti City by the governments of Djibouti, Somalia and Ethiopia. It is officially mandated with preserving the Somali language.[19]

As of 2013, Somali is also one of the featured languages available on Google Translate.[20]

Varieties

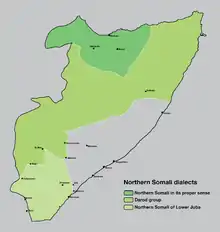

Somali linguistic varieties are broadly divided into three main groups: Afsoomali, Benadir and Maay.[21] Northern Somali (or Nsom[22]) forms the basis for Standard Somali.[21] It is spoken by more than 85% of the entire Somali population, with its speech area stretching from Djibouti, Northern Somalia, Somali Region of Ethiopia, North Eastern Kenya to most parts of Somalia[23] This widespread modern distribution is a result of a long series of southward population movements over the past ten centuries from the Gulf of Aden littoral.[24] Lamberti subdivides Northern Somali is into three dialects: Northern Somali proper (spoken in the northwest; he describes this dialect as Northern Somali in the proper sense), the Darod group (spoken in the northeast and along the eastern Ethiopia frontier; greatest number of speakers overall), and the Lower Juba group (spoken by northern Somali settlers in the southern riverine areas).[22]

Benadir (also known as Coastal Somali) is spoken on the central Indian Ocean seaboard, including Mogadishu. It forms a relatively smaller group. The dialect is fairly mutually intelligible with Northern Somali.[25]

Now there are other languages that are spoken in Somalia which are not necessarily Afsoomali. They may be a mixture of the Somali Languages and other indigenous Languages. Such a Language is Maay and is principally spoken by the Digil and Mirifle (Rahanweyn or Sab) clans in the southern regions of Somalia.[21] Its speech area extends from the southwestern border with Ethiopia to a region close to the coastal strip between Mogadishu and Kismayo, including the city of Baidoa.[25] Maay is not mutually comprehensible with Northern Somali, and it differs in sentence structure and phonology.[26] It is also not generally used in education or media. However, Maay speakers often use Standard Somali as a lingua franca,[25] which is learned via mass communications, internal migration and urbanization.[26]

Maay is not closely related with the Somali language in sentence structure and phonology is spoken by Jiddu, Dabarre, Garre and Tunni varieties that are also spoken by smaller Rahanweyn communities. Collectively, these languages present similarities with Oromo that are not found in mainstream Somali. Chief among these is the lack of pharyngeal sounds in the Rahanweyn/Digil and Mirifle languages, features which by contrast typify Somali but are not Somali. Although in the past frequently classified as dialects of Somali, more recent research by the linguist Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi has shown that these varieties, including Maay, constitute separate Cushitic languages.[27] The degree of divergence is comparable to that between Spanish and Portuguese.[28] Of the Digil varieties, Jiddu is the most incomprehensible to Benadir and Northern speakers.[29] Despite these linguistic differences, Somali speakers collectively view themselves as speaking a common language.[30]

These assumptions however has been contested by a more recent study by Deqa Hassan that tested the mutual intelligibility between Af-Maay and Af-Maxaa speakers (Northern Somali).

The study found that Af-Maay is partially mutually intelligible to Af-Maxaa (Northern Speakers) and that intelligibility increases with increased understanding of Standard Somali. Which implies understanding of standard Somali (Northern Somali) increases the chance of understanding Af-Maay. This accounts for the most significant linguistic factor that ties both language variations together. Furthermore Af-Maay is categorized as a Type 5 dialect for the overlapping common cultural history it shares with Af Maxaa speakers which explains its somewhat mutual intelligibility.[31]

Phonology

Somali has 22 consonant phonemes.[32]

| Bilabial | Labio dental |

Dental | Alveolar | Palato alveolar |

Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyn geal |

Glottal | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Plosive | b | t̪ | d̪ | ɖ | k | ɡ | q | ʔ | ||||||||||||||

| Affricate | t͡ʃ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Fricative | f | s | ʃ | x~χ | ħ | ʕ | h | |||||||||||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | |||||||||||||||||||

The consonants /b d̪ ɡ/ often weaken to [β ð ɣ] intervocalically.[35] The retroflex plosive /ɖ/ may have an implosive quality for some speakers, and intervocalically it can be realized as the flap [ɽ].[35] Some speakers produce /ħ/ with epiglottal trilling.[36] /q/ is often epiglottalized.[37]

The language has five basic vowels. Each has a front and back variation as well as long or short versions. This gives a distinct 20 pure vowel sounds. It also exhibits three tones: high, low and falling. Vowels harmonize within a harmonic group, so all vowels within the group must either be front or back. The Somali orthography does not distinguish between the front and back variants of vowels, however, as there are few minimal pairs.[38]

The syllable structure of Somali is (C)V(C). Root morphemes usually have a mono- or di-syllabic structure.

Pitch is phonemic in Somali, but it is debated whether Somali is a pitch accent or tonal language.[39] Andrzejewski (1954) posits that Somali is a tonal language,[40] whereas Banti (1988) suggests that it is a pitch accent language.[41]

Grammar

| Subject pronouns | Object pronouns | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Emphatic | Short | Emphatic | Short |

| 1. Sing. | anigu | aan | aniga | i(i) |

| 2. Sing. | adigu | aad | adiga | ku(u) |

| 3. Sing. m. | isagu | uu | isaga | (he) |

| 3. Sing. f. | iyadu | ay | iyada | (she) |

| 1. Pl. (inclusive) | innagu | aynu | innaga | ina/inoo |

| 1. Pl. (exclusive) | annagu | aannu | annaga | na/noo |

| 2. Pl. | idinku | aad | idinka | idin/idiin |

| 3. Pl. | iyagu | ay | iyaga | (u) |

Morphology

Somali is an agglutinative language, and also shows properties of inflection. Affixes mark many grammatical meanings, including aspect, tense and case.[42]

Somali has an old prefixal verbal inflection restricted to four common verbs, with all other verbs undergoing inflection by more obvious suffixation. This general pattern is similar to the stem alternation that typifies Cairene Arabic.[43]

Changes in pitch are used for grammatical rather than lexical purposes.[44] This includes distinctions of gender, number and case.[44] In some cases, these distinctions are marked by tone alone (e.g. Ínan, "boy"; inán, "girl").[45]

Somali has two sets of pronouns: independent (substantive, emphatic) pronouns and clitic (verbal) pronouns.[46] The independent pronouns behave grammatically as nouns, and normally occur with the suffixed article -ka/-ta (e.g. adiga, "you").[46] This article may be omitted after a conjunction or focus word. For example, adna meaning "and you..." (from adi-na).[46] Clitic pronouns are attached to the verb and do not take nominal morphology.[47] Somali marks clusivity in the first person plural pronouns; this is also found in a number of other East Cushitic languages, such as Rendille and Dhaasanac.[48]

As in various other Afro-Asiatic languages, Somali is characterized by polarity of gender, whereby plural nouns usually take the opposite gender agreement of their singular forms.[49][50] For example, the plural of the masculine noun dibi ("bull") is formed by converting it into feminine dibi.[49] Somali is unusual among the world's languages in that the object is unmarked for case while the subject is marked, though this feature is found in other Cushitic languages such as Oromo.[51]

Syntax

Somali is a subject–object–verb (SOV) language.[3] It is largely head final, with postpositions and with obliques preceding verbs.[52] These are common features of the Cushitic and Semitic Afroasiatic languages spoken in the Horn region (e.g. Amharic).[53] However, Somali noun phrases are head-initial, whereby the noun precedes its modifying adjective.[52][54] This pattern of general head-finality with head-initial noun phrases is also found in other Cushitic languages (e.g. Oromo), but not generally in Ethiopian Semitic languages.[52][55]

Somali uses three focus markers: baa, ayaa and waxa(a), which generally mark new information or contrastive emphasis.[56] Baa and ayaa require the focused element to occur preverbally, while waxa(a) may be used following the verb.[57]

Vocabulary

Somali loanwords can be divided into those derived from other Afroasiatic languages (mainly Arabic), and those of Indo-European extraction (mainly Italian).[58]

Somali's main lexical borrowings come from Arabic, and are estimated to constitute about 20% of the language's vocabulary.[59] This is a legacy of the Somali people's extensive social, cultural, commercial and religious links and contacts with nearby populations in the Arabian peninsula. Arabic loanwords are most commonly used in religious, administrative and education-related speech (e.g. aamiin for "faith in God"), though they are also present in other areas (e.g. kubbad-da, "ball").[58] Soravia (1994) noted a total of 1,436 Arabic loanwords in Agostini a.o. 1985,[60] a prominent 40,000-entry Somali dictionary.[61] Most of the terms consisted of commonly used nouns. These lexical borrowings may have been more extensive in the past since a few words that Zaborski (1967:122) observed in the older literature were absent in Agostini's later work.[60] In addition, the majority of personal names are derived from Arabic.[62]

The Somali language also contains a few Indo-European loanwords that were retained from the colonial period.[13] Most of these lexical borrowings come from English and Italian and are used to describe new objects or modern concepts (e.g. telefishen-ka, "television"; raadia-ha, "radio").[63] There are as well 300 directly Romance loans, such as garawati for "tie" (from the Italian cravatta).

Indeed, the most used loanwords from the Italian are "ciao" as a friendly salute, "dimuqraadi" from Italian "democratico" (democratic), "mikroskoob" from "microscopio (microscope), "Jalaato" from "gelato" (ice cream), "baasto" from "pasta" (pasta), "bataate" from "patate" (potato), "bistoolad" from "pistol" (pistol), "fiyoore" from "fiore" (flower) and "injinyeer" from "ingegnere" (engineer).[64] Somalis call their calendar months as Soon, soonfur, siditaal, carafa....but these changed recently. Furthermore, all the months in Somali language are now loaned words from the Italian, like "Febraayo" that comes from "febbraio" (February).

Additionally, Somali contains lexical terms from Persian, Urdu and Hindi that were acquired through historical trade with communities in the Near East and South Asia (e.g. khiyaar "cucumber" from Persian: خيار khiyār).[63] Some of these words were also borrowed indirectly via Arabic.[63][65]

As part of a broader governmental effort to ensure and safeguard the primacy of the Somali language, the past few decades have seen a push in Somalia toward replacement of loanwords in general with their Somali equivalents or neologisms. To this end, the Supreme Revolutionary Council during its tenure officially prohibited the borrowing and use of English and Italian terms.[13]

Writing system

Archaeological excavations and research in Somalia uncovered ancient inscriptions in a distinct writing system.[66] In an 1878 report to the Royal Geographical Society of Great Britain, scientist Johann Maria Hildebrandt noted upon visiting the area that "we know from ancient authors that these districts, at present so desert, were formerly populous and civilised[...] I also discovered ancient ruins and rock-inscriptions both in pictures and characters[...] These have hitherto not been deciphered."[67] According to Somalia's Ministry of Information and National Guidance, this script represents the earliest written attestation of Somali.[66]

Besides Ahmed's Latin script, other orthographies that have been used for centuries for writing the Somali language include the long-established Arabic script and Wadaad writing.[68] According to Bogumił Andrzejewski, this usage was limited to Somali clerics and their associates, as sheikhs preferred to write in the liturgical Arabic language. Various such historical manuscripts in Somali nonetheless exist, which mainly consist of Islamic poems (qasidas), recitations and chants.[69] Among these texts are the Somali poems by Sheikh Uways and Sheikh Ismaaciil Faarah. The rest of the existing historical literature in Somali principally consists of translations of documents from Arabic.[70]

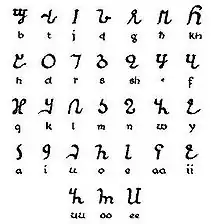

Since then a number of writing systems have been used for transcribing the Somali language. Of these, the Somali Latin alphabet, officially adopted in 1972, is the most widely used and recognised as official orthography of the state.[71] The script was developed by a number of leading scholars of Somali, including Musa Haji Ismail Galal, B. W. Andrzejewski and Shire Jama Ahmed specifically for transcribing the Somali language, and uses all letters of the English Latin alphabet except p, v and z.[72][73] There are no diacritics or other special characters except the use of the apostrophe for the glottal stop, which does not occur word-initially. There are three consonant digraphs: DH, KH and SH. Tone is not marked, and front and back vowels are not distinguished.

Writing systems developed in the twentieth century include the Osmanya, Borama and Kaddare alphabets, which were invented by Osman Yusuf Kenadid, Abdurahman Sheikh Nuur and Hussein Sheikh Ahmed Kaddare, respectively.[74]

Sample text

Numbers

| English | Somali |

|---|---|

| One | kow |

| Two | laba |

| Three | saddex |

| Four | afar |

| Five | shan |

| Six | lix |

| Seven | toddoba |

| Eight | siddeed |

| Nine | sagaal |

| Ten | toban |

| English | Somali |

|---|---|

| Eleven | kow iyo toban |

| Twelve | laba iyo toban |

| Thirteen | saddex iyo toban |

| Fourteen | afar iyo toban |

| Fifteen | shan iyo toban |

| Sixteen | lix iyo toban |

| Seventeen | toddoba iyo toban |

| Eighteen | sideed iyo toban |

| Nineteen | sagaal iyo toban |

| Twenty | labaatan |

| English | Somali |

|---|---|

| Thirty | soddon |

| Forty | afartan |

| Fifty | konton |

| Sixty | lixdan |

| Seventy | todobaatan |

| Eighty | siddeetan |

| Ninety | sagaashan |

| English | Somali |

|---|---|

| One hundred | boqol |

| One thousand | kun |

| One million | milyan |

| One billion | bilyan |

Days of the week

| English | Somali |

|---|---|

| Sunday | Axad |

| Monday | Isniin |

| Tuesday | Salaasa/Talaado |

| Wednesday | Arbacaa/Arbaco |

| Thursday | Khamiis |

| Friday | Jimco |

| Saturday | Sabti |

Months of the year

| English | Somali |

|---|---|

| January | Janaayo |

| February | Febraayo |

| March | Maarso |

| April | Abriil |

| May | Maajo |

| June | Juun |

| July | Luuliyo |

| August | Agoosto |

| September | Sebteembar |

| October | Oktoobar |

| November | Nofeembar |

| December | Diseembar |

See also

References

- "Somali alphabets, pronunciation and language". Omniglot. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- "cldr/so.xml at master · unicode-org/cldr". Unicode. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- "Somali". SIL International. 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.), English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 3-12-539683-2

- "Somali". Collins Dictionary. Retrieved on 21 September 2013

- Saeed (1999:107)

- "Constitution of the Republic of Somaliland" (PDF). Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- Lewis (1998:11)

- Lecarme & Maury (1987:22)

- Dubnov (2003:9)

- Saeed (1999:3)

- "The Federal Republic of Somalia - Provisional Constitution" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- Ammon & Hellinger (1992:128–131)

- Dubnov (2003:10)

- "Somali Media Mapping Report" (PDF). Somali Media Mapping. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- Kizitus Mpoche, Tennu Mbuh, eds. (2006). Language, literature, and identity. Cuvillier. pp. 163–164. ISBN 3-86537-839-0.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Ethnologue - Djibouti - Languages". Ethnologue. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5g2xHqL7Eyo

- "Regional Somali Language Academy Launched in Djibouti". COMESA Regional Investment Agency. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- "Google Translate - now in 80 languages". Google Translate. 10 December 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- Dalby (1998:571)

- Lamberti, Marcello (1986). Map of Somali dialects in the Somalia Democratic Republic (PDF). H. Buske. ISBN 9783871186905.

- Mundus, Volumes 23-24. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft. 1987. p. 205.

- Andrzejewski & Lewis (1964:6)

- Saeed (1999:4)

- "Maay - A language of Somalia". Ethnologue. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- Abdullahi (2001:9)

- Lewis, I. M. (1998-01-01). Saints and Somalis: Popular Islam in a Clan-based Society. The Red Sea Press. p. 74. ISBN 9781569021033.

- "Report Somalia: Language situation and dialects" (PDF). Country of Origin Information Centre (Landinfo). 2011. p. 6.

- Somali nationalism: international politics and the drive for unity in the Horn of Africa. Department of Linguistics and the African Studies Center, University of California, Los Anglos. 1963. p. 24. ISBN 9780674818255.

- Somali Dialects in the United States: How intelligible is Af-Maay to Speakers of Af-Maxaa? by Deqa Hassan (Minnesota State University - Mankato)

- Saeed (1999:7)

- Saeed (1999:7–10)

- Gabbard (2010:6)

- Saeed (1999:8)

- Gabbard (2010:14)

- Edmondson, Esling & Harris (n.d.:5)

- "Somali ATR harmony". www.ling.upenn.edu. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- Keith Brown, Sarah Ogilvie (2010). Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Elsevier. p. 987. ISBN 978-0080877754.

- Andrzejewski, Bogumit Witalis (1954). "Is Somali a Tone-language?", Proceedings of the Twenty-Third International Congress of Orientalists. Royal Asiatic Society. pp. 367–368. OCLC 496050266.

- Banti, Giorgio (1988). "Two Cushitic Systems: Somali and Oromo nouns", Autosegmental Studies on Pitch Accent (PDF). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 11–50. ISBN 3110874261. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- Dubnov (2003:11)

- Kraska, Iwona (2007). Analogy: the relation between lexicon and grammar. Lincom Europa. p. 140. ISBN 978-3895868986.

- Saeed (1999:21)

- Saeed (1999:19)

- Saeed (1999:68)

- Saeed (1999:72)

- Weninger (2011:43)

- Tosco, Mauro; Department of Anthropology; Indiana University (2000). "Is There an "Ethiopian Language Area"?". Anthropological Linguistics. 42 (3): 349. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- Zwicky & Pullum (1983:389)

- John I. Saeed (1984). The Syntax of Focus & Topic in Somali. H. Buske. p. 66. ISBN 3871186724.

- Heine & Nurse (2000:253)

- Klaus Wedekind, Charlotte Wedekind, Abuzeinab Musa (2007). A learner's grammar of Beja (East Sudan): grammar, texts and vocabulary (Beja-English and English-Beja). Rüdiger Köppe Verlag. p. 10. ISBN 978-3896455727.

- Saeed (1999:164, 173)

- Fisiak (1997:53)

- Saeed (1999:117)

- Saeed (1999:240)

- Dubnov (2003:71)

- Laitin (1977:25)

- Versteegh (2008:273)

- Saeed (1999:5)

- Saeed (1999:2)

- Dubnov (2003:73)

- "Italian and English Loanwords in Somali, by Alberto Mioni". Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- Sheik-ʻAbdi (1993:45)

- Ministry of Information and National Guidance, Somalia, The writing of the Somali language, (Ministry of Information and National Guidance: 1974), p.5

- Royal Geographical Society (Great Britain), Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of London, Volume 22, "Mr. J. M. Hildebrandt on his Travels in East Africa", (Edward Stanford: 1878), p. 447.

- "Omniglot - Somali writing scripts". Omniglot. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- Andrezewski, B. W. In Praise of Somali Literature. Lulu. pp. 130–131. ISBN 1291454535. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- Andrezewski, B. W. In Praise of Somali Literature. Lulu. p. 232. ISBN 1291454535. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- Economist Intelligence Unit (Great Britain), Middle East annual review, (1975), p.229

- Abdullahi, Mohamed Diriye (2001). Culture and Customs of Somalia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-313-31333-2.

- Lewis, I. M. (1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. James Currey Publishers. ISBN 978-0-85255-280-3.

- Laitin (1977:86–87)

Sources

- Abdullahi, Mohamed Diriye (2001). Culture and Customs of Somalia. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-31333-2.

- Ammon, Ulrich; Hellinger, Marlis (1992). Status Change of Languages. Walter de Gruyter.

- Andrzejewski, B.; Lewis, I. (1964). Somali poetry: an introduction. Clarendon Press.

- Dalby, Andrew (1998). Dictionary of languages: the definitive reference to more than 400 languages. Columbia University Press.

- Dubnov, Helena (2003). A Grammatical Sketch of Somali. Koln: Rudiger Koppe Verlag.

- Edmondson, Jerold; Esling, John; Harris, Jimmy (n.d.), Supraglottal cavity shape, linguistic register, and other phonetic features of Somali (PDF)

- Fisiak, Jacek (1997). Linguistic reconstruction and typology. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-014905-0.

- Gabbard, Kevin (2010), A Phonological Analysis of Somali and the Guttural Consonants, hdl:1811/46639

- Heine, Bernd; Nurse, Derek (2000). African Languages: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66629-9.

- Laitin, David (1977). Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience. University Of Chicago Press.

- Lecarme, Jacqueline; Maury, Carole (1987). "A software tool for research in linguistics and lexicography: Application to Somali". Computers and Translation. Paradigm Press. 2: 21–36. doi:10.1007/BF01540131. S2CID 6515240.

- Lewis, I. (1998). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho. Red Sea Press.

- Saeed, John (1999). Somali. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. ISBN 1-55619-224-X.

- Sheik-ʻAbdi, ʻAbdi ʻAbdulqadir (1993). Divine madness: Moḥammed ʻAbdulle Ḥassan (1856-1920). Zed Books.

- Versteegh, Kees (2008). Encyclopedia of Arabic language and linguistics, Volume 4. Brill. ISBN 978-9004144767.

- Weninger, Stefan (2011). Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-025158-6.

- Zwicky, Arnold; Pullum, Geoffrey (1983). "Phonology in Syntax: The Somali Optional Agreement Rule" (PDF). Natural Language & Linguistic Theory. 1 (3): 385–402. doi:10.1007/bf00142471. S2CID 170420275.

Further reading

- Abdullahi, Mohamed Diriye (2000). Le Somali, dialectes et histoire. Ph.D. dissertation, Université de Montréal.

- Armstrong, L.E. (1964). "The phonetic structure of Somali," Mitteilungen des Seminars für Orientalische Sprachen Berlin 37/3:116-161.

- Bell, C.R.V. (1953). The Somali Language. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

- Berchem, Jörg (1991). Referenzgrammatik des Somali. Köln: Omimee.

- Cardona, G.R. (1981). "Profilo fonologico del somalo," Fonologia e lessico. Ed. G.R. Cardona & F. Agostini. Rome: Dipartimento per la Cooperazione allo Sviluppo; Comitato Tecnico Linguistico per l'Università Nazionale Somala, Ministero degli Affari Esteri. Volume 1, pages 3–26.

- Dobnova, Elena Z. (1990). Sovremennyj somalijskij jazyk. Moskva: Nauka.

- Puglielli, Annarita (1997). "Somali Phonology," Phonologies of Asia and Africa, Volume 1. Ed. Alan S. Kaye. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. Pages 521-535.

- Lamberti, M. (1986). Die Somali-Dialekte. Hamburg: Buske.

- Lamberti, M. (1986). Map of the Somali-Dialects in the Somali Democratic Republic. Hamburg: Buske.

- Saeed, John Ibrahim (1987). Somali Reference Grammar. Springfield, VA: Dunwoody Press.

External links

| Somali edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Somali phrasebook. |

- Somali Language Page: Resources, links and information on the Somali language.

- Hooyo.Web - Somali Grammar

- Somali Language and Linguistics: A Bibliography

- Learn101 - Learn Somali

- Virtual keyboard for historical Osmanya script. Lexilogos.

- Digital Dialects - Somali language learning games

- Enhancing the Quality of Google Somali Translations