Ontogeny

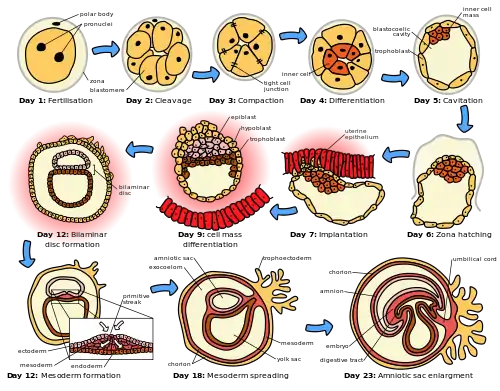

Ontogeny (also ontogenesis) is the origination and development of an organism (both physical and psychological, e.g., moral development[1]), usually from the time of fertilization of the egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to the study of the entirety of an organism's lifespan.

Ontogeny is the developmental history of an organism within its own lifetime, as distinct from phylogeny, which refers to the evolutionary history of a species. In practice, writers on evolution often speak of species as "developing" traits or characteristics. This can be misleading. While developmental (i.e., ontogenetic) processes can influence subsequent evolutionary (e.g., phylogenetic) processes[2] (see evolutionary developmental biology and recapitulation theory), individual organisms develop (ontogeny), while species evolve (phylogeny).

Ontogeny, embryology and developmental biology are closely related studies and those terms are sometimes used interchangeably. Aspects of ontogeny are morphogenesis, the development of form; tissue growth; and cellular differentiation. The term ontogeny has also been used in cell biology to describe the development of various cell types within an organism.[3]

Ontogeny is a useful field of study in many disciplines, including developmental biology, developmental psychology, developmental cognitive neuroscience, and developmental psychobiology.

Ontogeny is used in anthropology as "the process through which each of us embodies the history of our own making."[4]

Etymology

The word ontogeny comes from the Greek ὄν, on (gen. ὄντος, ontos), i.e. "being; that which is", which is the present participle of the verb εἰμί, eimi, i.e. "to be, I am", and from the suffix -geny from the Greek -γένεια -geneia, which expresses the concept of "mode of production".[5]

Nature and nurture

A seminal 1963 paper by Niko Tinbergen named ontogeny as one of the four primary questions of biology, along with Huxley's three others: causation, survival value and evolution.[6] Tinbergen emphasized that the change of behavioral machinery during development was distinct from the change in behavior during development. "We can conclude that the thrush itself, i.e. its behavioral machinery, has changed only if the behavior change occurred while the environment was held constant...When we turn from description to causal analysis, and ask in what way the observed change in behavior machinery has been brought about, the natural first step is to try and distinguish between environmental influences and those within the animal...In ontogeny the conclusion that a certain change is internally controlled (is "innate") is reached by elimination. " (p. 424) Tinbergen was concerned that the elimination of environmental factors is difficult to establish, and the use of the word "innate" is often misleading.

Ontogenetic allometry

Most organisms undergo allometric changes in shape as they grow and mature, while others engage in metamorphosis. Even "reptiles" (non-avian sauropsids, e.g., crocodilians, turtles, snakes,[7] lizards[8]), in which the offspring are often viewed as miniature adults, show a variety of ontogenetic changes in morphology and physiology.[9]

Anthropological application

Comparing ourselves to others is something humans do all the time. "In doing so we are acknowledging not so much our sameness to others or our difference, but rather the commonality that resides in our difference. In other words, because each one of us is at once remarkably similar to, and remarkably different from, all other humans, it makes little sense to think of comparison in terms of a list of absolute similarities and a list of absolute differences. Rather, in respect of all other humans, we find similarities in the ways we are different from one another and differences in the ways we are the same. That we are able to do this is a function of the genuinely historical process that is human ontogeny".[4]

See also

- Recapitulation theory, the idea that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny

- Organogenesis

- Ontogeny (psychoanalysis)

- Phylogenetics

- Phylogeny (psychoanalysis)

- Noogenesis

- Apoptosis - Cell death in specific locations due to inherited genetic instructions.

Notes and references

- Tomasello, Michael (27 September 2018). "The Normative Turn in Early Moral Development". Human Development. 61 (4–5): 248–263. doi:10.1159/000492802. S2CID 149612818.

- Gould, S.J. (1977). Ontogeny and Phylogeny. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

- Thiery, Jean Paul (1 December 2003). "Epithelial–mesenchymal transitions in development and pathologies". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 15 (6): 740–746. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.006. PMID 14644200.

- Toren, Christina. "Comparison and ontogeny." Anthropology, by comparison (2002): 187.

- See -geny in the Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 1989; online version March 2011, accessed 9 May 2011. Earlier version first published in New English Dictionary, 1898.

- Niko Tinbergen (1963). "On aims and methods of ethology" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. 20 (4): 410–433. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1963.tb01161.x. See page 411.

- Pough, F. H. (1978). "Ontogenetic changes in endurance in water snakes (Natrix sipedon): Physiological correlates and ecological consequences". Copeia. 1978 (1): 69–75. doi:10.2307/1443823. JSTOR 1443823.

- Garland Jr, T. (1985). "Ontogenetic and individual variation in size, shape and speed in the Australian agamid lizard Amphibolurus nuchalis". Journal of Zoology. 207 (3): 425–439. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.211.1730. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1985.tb04941.x.

- Garland Jr., T.; Else, P. L. (1987). "Seasonal, sexual, and individual variation in endurance and activity metabolism in lizards". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 252 (3): R439–R449. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.1987.252.3.r439. PMID 3826408. S2CID 15804764.

External links

Media related to Morphogenesis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Morphogenesis at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of ontogeny at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of ontogeny at Wiktionary