Operation Neuland

Operation Neuland (New Land) was the German Navy's code name for the extension of unrestricted submarine warfare into the Caribbean Sea during World War II. U-boats demonstrated range to disrupt United Kingdom petroleum supplies and United States aluminum supplies which had not been anticipated by Allied pre-war planning. Although the area remained vulnerable to submarines for several months, U-boats never again enjoyed the opportunities for success resulting from the surprise achieved by the submarines participating in this operation.

| Operation Neuland | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Atlantic Campaign of World War II | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 11 submarines |

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

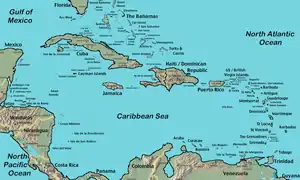

Background

The Caribbean was strategically significant because of Venezuelan oil fields in the southeast and the Panama Canal in the southwest. The Royal Dutch Shell oil refinery on Dutch-owned Curaçao, processing eleven million barrels per month, was the largest in the world; the refinery at Pointe-à-Pierre on Trinidad was the largest in the British Empire; and there was another large refinery on Dutch-owned Aruba. The British Isles required four oil tankers of petroleum daily during the early war years, and most of it came from Venezuela, through Curaçao, after Italy blocked passage through the Mediterranean Sea from the Middle East.[1]

The Caribbean held additional strategic significance to the United States. The southern United States Gulf of Mexico coastline, including petroleum facilities and Mississippi River trade, could be defended at two points. The United States was well positioned to defend the Straits of Florida but was less able to prevent access from the Caribbean through the Yucatán Channel. Bauxite was the preferred ore for aluminum, and one of the few strategic raw materials not available within the continental United States. United States military aircraft production depended upon bauxite imported from the Guianas along shipping routes paralleling the Lesser Antilles.[2]

United States Navy VP-51 Consolidated PBY Catalinas began neutrality patrols along the Lesser Antillies from San Juan, Puerto Rico on 13 September 1939.[3] The United Kingdom had established military bases on Trinidad; and British troops occupied Aruba, Curaçao and Bonaire soon after the Netherlands were captured by Nazi Germany. The French island of Martinique was perceived as a possible base for Axis ships as British relationships with Vichy France deteriorated following the Second Armistice at Compiègne. The September 1940 Destroyers for Bases Agreement enabled the United States to build bases in British Guiana, and on the islands of Great Exuma, Jamaica, Antigua, Saint Lucia and Trinidad.[4]

Concept

Declaration of war on 8 December 1941 removed United States neutrality assertions which had previously protected trade shipping in the Western Atlantic. The relatively ineffective anti-submarine warfare (ASW) measures along the United States Atlantic coast observed by U-boats participating in Operation Paukenschlag encouraged utilizing the range of German Type IX submarines to explore conditions in what had previously been the southern portion of a declared Pan American neutrality zone. A 15 January 1942 meeting in Lorient included former Hamburg America Line captains with Caribbean experience to brief commanding officers of U-156, U-67, U-502, U-161 and U-129 about conditions in the area. The first three U-boats sailed on 19 January with orders to simultaneously attack Dutch refinery facilities on 16 February. U-161 sailed on 24 January to attack Trinidad, and U-129 followed on 26 January. U-126 sailed on 2 February to patrol the Windward Passage between Cuba and Hispaniola; and five large Italian submarines sailed from Bordeaux to patrol the Atlantic side of the Lesser Antilles. These eleven submarines would patrol independently to disperse Allied ASW resources until exhaustion of food, fuel or torpedoes required them to return to France.[5]

Implementation

U-156

The second patrol of U-156 was under the command of Werner Hartenstein. Surfacing after nightfall on the evening on February 15, Hartenstein waited 2 miles off shore before commencing his attack at 0131 on February 16, 1942 when he fired two torpedoes at the tankers SS Pedernales and SS Oranjestad laying at anchor outside Aruba's San Nicolaas. Ten minutes later, U-156 moved to within 3/4 mile of the Lago refinery and prepared to bombard the facility. However, a crewman failed to remove the tampion from the muzzle of the 10.5 cm SK C/32 naval gun, and the first shell detonated within the barrel. One gunner was killed, another seriously injured, and the muzzle of the gun barrel was splayed open. Following the attack, the U-156 sailed past Oranjestad, 14 miles to the west and fired three torpedoes at the Shell tanker Arkansas berthed at the Eagle Pier. One struck the ship, causing minor damage while one missed its mark and disappeared in the water while the third beached itself. A few days later, four Dutch marines were killed as they attempted to disarm the torpedo. Hartenstein kept the U-156 submerged north of Aruba after day break. At nightfall the crew buried the sailor who died when the gun exploded, and the captain received permission to sail to Martinique where the injured crewman was put ashore. The crew used hacksaws to shorten the damaged gun barrel by 40 centimeters, and used the sawed-off gun to sink two ships encountered after all torpedoes had been expended sinking two other ships. U-156 started home on 28 February 1942.[6]

| Date[7] | Ship[7] | Flag[7] | Tonnage (GRT)[7] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 February 1942 | Pedernales | 4,317 | Tanker torpedoed outside San Nicolaas harbor, but later repaired | |

| 16 February 1942 | Oranjestad | 2,396 | Tanker torpedoed outside San Nicolaas harbor, and capsized in 48 seconds[8] | |

| 16 February 1942 | Arkansas | 6,452 | Tanker torpedoed at Eagle Pier near Oranjestad but later repaired | |

| 20 February 1942 | Delplata | 5,127 | Freighter torpedoed at 14°45′N 62°10′W[9] | |

| 25 February 1942 | La Carriere | 5,685 | Tanker | |

| 27 February 1942 | Macgregor | 2,498 | Freighter sunk by gunfire | |

| 28 February 1942 | Oregon | 7,017 | 6 crewman killed aboard tanker sunk by gunfire at 20°44′N 67°52′W[10] |

U-67

The third patrol of U-67 was under the command of Günther Müller-Stöckheim. In coordination with the attack on Aruba U-67 moved into Curaçao's Willemstad harbor shortly after midnight on 16 February to launch six torpedoes at three anchored tankers. The four bow torpedoes hit, but failed to explode. The two torpedoes from the stern tubes were effective on the third tanker.[11]

| Date[12] | Ship[12] | Flag[12] | Tonnage (GRT)[12] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 February 1942 | Rafaela | 3,177 | Tanker torpedoed in Willemstad harbor, but later repaired | |

| 21 February 1942 | Kongsgaard | 9,467 | Tanker | |

| 14 March 1942 | Penelope | 8,436 | Tanker |

U-502

The third patrol of U-502 was under the command of Jürgen Von Rosensteil. In coordination with the attacks on Aruba and Willemstad, U-502 waited to ambush shallow draft Lake Maracaibo crude oil tankers en route to the refineries. After three tankers were reported missing, the Chinese crews of surviving tankers refused to sail; and Associated Press broadcast a report that tanker traffic had been halted in the area. U-502 moved north and started home via the Windward Passage after launching its last torpedoes on 23 February.[13]

| Date[14] | Ship[14] | Flag[14] | Tonnage[14] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 February 1942 | Tia Juana | 2,395 | Shallow-draught 'Lake Maracaibo' crude oil tanker | |

| 16 February 1942 | Monagas | 2,650 | Shallow-draught 'Lake Maracaibo' crude oil tanker | |

| 16 February 1942 | San Nicholas | 2,391 | Shallow-draught 'Lake Maracaibo' crude oil tanker | |

| 22 February 1942 | J.N.Pew | 9,033 | Tanker torpedoed at 12°40′N 74°00′W,33 killed; 3 survivors[9] | |

| 23 February 1942 | Thallia | 8,329 | Tanker | |

| 23 February 1942 | Sun | 9,002 | No casualties aboard. Tanker damaged by torpedo at 13°02′N 70°41′W[15] |

U-161

The second patrol of U-161 was under the command of Albrecht Achilles. Achilles and his first watch officer Bender had both visited Trinidad while employed by Hamburg America Line before the war. U-161 entered Trinidad's Gulf of Paria harbor at periscope depth during daylight through a deep, narrow passage or Boca. An electronic submarine detection system registered its passage at 0930 on 18 February 1942, but the signal was dismissed as caused by a patrol boat. After spending the day resting on the bottom of the harbor, U-161 surfaced after dark to torpedo two anchored ships. U-161 then left the gulf with decks awash and running lights illuminated to resemble one of the harbor small craft; and then moved off to the northwest before returning to sink a ship outside the Boca. After sunset on 10 March 1942 U-161 silently entered the shallow, narrow entrance of Castries harbor surfaced on electric motors to torpedo two freighters at dockside; and then raced out under fire from machine guns. The two freighters had just arrived with supplies to construct the new US base; and the harbor previously considered immune to submarine attack was later fitted with an anti-submarine net. U-161 started home on 11 March 1942.[16]

| Date[17] | Ship[17] | Flag[17] | Tonnage[17] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 February 1942 | British Consul | 6,940 | Tanker torpedoed in Gulf of Paria, but later repaired | |

| 19 February 1942 | Mokihana | 7,460 | No casualties aboard freighter torpedoed in Gulf of Paria, but later repaired[18] | |

| 21 February 1942 | Circe Shell | 8,207 | Tanker | |

| 23 February 1942 | Lihue | 7,001 | No casualties aboard freighter torpedoed at 14°30′N 64°45′W[19] | |

| 7 March 1942 | Uniwaleco | 9,755 | Tanker exploded with no survivors[20] | |

| 10 March 1942 | Lady Nelson | 7,970 | Freighter torpedoed in Castries harbor, but later repaired | |

| 10 March 1942 | Umtata | 8,141 | Freighter torpedoed in Castries harbor, but later repaired | |

| 14 March 1942 | Sarniadoc | 1,940 | Freighter exploded and disappeared 30 seconds after torpedo impact[21] 21 lost no survivors | |

| 15 March 1942 | Acacia | 1,130 | USCG lighthouse tender sunk by gunfire south of Haiti |

Luigi Torelli

Luigi Torelli under the command of Antonio de Giacomo sank two ships.[22]

| Date[23] | Ship[22] | Flag[22] | Tonnage[22] | Notes[22] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 February | Scottish Star | 7,300 GRT | freighter | |

| 25 February | Esso Copenhagen | 9,200 GRT | tanker |

U-129

Under the command of Nicolai Clausen U-129 spent its fourth patrol intercepting bauxite freighters southeast of Trinidad.[24] The unexpected sinkings caused a temporary halt to merchant ship sailings. The Allies broadcast suggested routes for unescorted merchant ships to follow when sailings resumed. The U-boats received the broadcast and were waiting at the suggested locations.[25]

| Date[26] | Ship[26] | Flag[26] | Tonnage[26] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 February | Nordvangen | 2,400 GRT | tanker sunk with no survivors[27] | |

| 23 February | George L. Torian | 1,754 GRT | freighter | |

| 23 February | West Zeda | 5,658 GRT | no casualties aboard bauxite freighter[28] torpedoed at 09°13′N 69°04′W[9] | |

| 23 February | Lennox | 1,904 GRT | bauxite freighter | |

| 28 February | Bayou | 2,605 GRT | freighter | |

| 3 March | Mary | 5,104 GRT | bauxite freighter[29] torpedoed at 08°25′N 52°50′W[30] | |

| 7 March | Steel Age | 6,188 GRT | 33 killed;sole survivor taken captive from freighter torpedoed at 06°45′N 53°15′W[30] |

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci under the command of Luigi Longanesi-Cattani sank one Allied ship[22] and a neutral Brazilian freighter. There were no survivors from the Brazilian ship, and the sinking was not revealed.[31]

| Date[32] | Ship[32] | Flag[32] | Tonnage[32] | Notes[32] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 February 1942 | Cabadelo | 3,775 GRT | torpedoed at 16°00′N 42°30′W; all 54 hands lost | |

| 28 February | Everasma | 3,644 GRT | freighter torpedoed at 16°00′N 49°00′W |

U-126

U-126 patrolled the Windward Passage under the command of Ernst Bauer.[33]

| Date[34] | Ship[34] | Flag[34] | Tonnage[34] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 March | Gunny | 2,362 GRT | freighter | |

| 5 March | Mariana | 3,110 GRT | no survivors from freighter torpedoed at 22°14′N 71°23′W[30] [36 lost] | |

| 7 March | Barbara | 4,637 GRT | freighter torpedoed at 20°00′N 73°56′W[35] | |

| 7 March | Cardonia | 5,104 GRT | freighter torpedoed at 19°53′N 73°27′W[35] | |

| 8 March | Esso Bolivar | 10,389 GRT | tanker damaged by torpedoes within sight of Guantánamo[36] | |

| 9 March | Hanseat | 8,241 GRT | tanker | |

| 12 March | Texan | 7,005 GRT | freighter torpedoed at 21°32′N 76°24′W[37] | |

| 12 March | Olga | 2,496 GRT | freighter torpedoed at 23°39′N 77°00′W[37] | |

| 13 March | Colabee | 5,518 GRT | freighter damaged by torpedoes at 22°14′N 77°35′W[37] |

Enrico Tazzoli

The large 1,331-ton Enrico Tazzoli under the command of Carlo Fecia di Cossato sank six ships.[22]

| Date[38] | Ship[38] | Flag[38] | Tonnage[38] | Notes[38] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 March | Astrea | 1,406 GRT | freighter | |

| 6 March | Tonsbergfjord | 3,156 GRT | freighter torpedoed at 31°22′N 68°05′W with 1 killed | |

| 8 March | Montevideo | 5,785 GRT | freighter torpedoed at 29°13′N 69°35′W with 14 killed | |

| 10 March | Cygnet | 3,628 GRT | freighter torpedoed at 24°05′N 74°20′W with no casualties | |

| 13 March | Daytonian | 6,434 GRT | freighter torpedoed at 26°33′N 74°43′W with 1 killed | |

| 15 March | Athelqueen | 8,780 GRT | tanker torpedoed at 26°50′N 75°40′W with 3 killed |

Giuseppe Finzi

The large 1,331-ton Giuseppe Finzi under the command of Ugo Giudice sank three ships.[22]

| Date[39] | Ship[40] | Flag[40] | Tonnage[40] | Notes[40] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 March | Melpomene | 7,000 GRT | tanker | |

| 7 March | Skåne | 4,500 GRT | freighter | |

| 10 March | Charles Racine | 10,000 GRT | tanker torpedoed with no survivors[36] |

Morosini

Marcello class submarine Morosini under the command of Athos Fraternale sank three ships.[22]

| Date[41] | Ship[41] | Flag[41] | Tonnage[41] | Notes[41] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 March | Stangarth | 5,966 GRT | freighter torpedoed at 22°45′N 57°40′W | |

| 15 March | Oscilla | 6,341 GRT | tanker torpedoed with 4 killed | |

| 23 March | Peder Bogen | 9,741 GRT | tanker torpedoed at 24°53′N 57°30′W with no casualties |

Results

The Aruba refinery was within deck gun range of deep water. Grand Admiral Erich Raeder would have preferred shelling the refinery as the opening action of Operation Neuland. On the basis of experience with the relative damage caused by deck guns in comparison to torpedoes, U-boat officers chose to begin by torpedoing tankers to cause large fires of spreading oil. Results of the initial attacks on Aruba and Curaçao were diminished by weapon failures; and subsequent attempts to shell the Aruba refinery were discouraged by defensive fire from larger numbers of larger caliber coastal artillery and patrols by alerted aircraft and submarine chasers.[42]

An important link in petroleum product transport from Venezuelan oil fields was a fleet of small tankers designed to reach the wells in shallow Lake Maracaibo and transport crude oil to the refineries. Approximately ten percent of these tankers were destroyed on the first day of Operation Neuland. Surviving tankers were temporarily immobilized when their Chinese crews mutinied and refused to sail without ASW escort.[43] Refinery output declined while the mutineers were jailed until sailings could resume.[44]

Torpedoing ships within defended harbors was relatively unusual through the battle of the Atlantic. U-boats more commonly deployed mines to permit a stealthy exit. Although results were perceived as less significant, the difficulty of attacks in the Gulf of Paria and Castries by U-161 was comparable to Günther Prien's penetration of Scapa Flow.[45]

Patrol of the Windward Passage by U-126 was well timed to exploit dispersion of ASW forces north and south. U-126 sank some ships within sight of Guantanamo Bay Naval Base.[46]

Neuland and Paukenschlag were opened with similar numbers of U-boats; but the effectiveness of Neuland was enhanced by coordination with Italian submarines. The level of success by Italian submarines against a concentration of undefended ships sailing independently was seldom repeated and marked a high point of effective Axis cooperation in the battle of the Atlantic.[22]

See also

Sources

- Blair, Clay Hitler's U-Boat War: The Hunters 1939-1942 Random House (1996) ISBN 0-394-58839-8

- Cressman, Robert J. The Official Chronology of the U.S.Navy in World War II Naval Institute Press (2000) ISBN 1-55750-149-1

- Kafka, Roger & Pepperburg, Roy L. Warships of the World Cornell Maritime Press (1946)

- Kelshall, Gaylord T.M. The U-Boat War in the Caribbean United States Naval Institute Press (1994) ISBN 1-55750-452-0

- Morison, Samuel Eliot, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II (volume I) The Battle of the Atlantic September 1939-May 1943 Little, Brown and Company (1975)

Notes

- Kelshall pp.7-22

- Kelshall pp.7-18

- Scarborough, William E. "The Neutralitv Patrol: To Keep Us Out of World War II?" pp.18-23 NAVAL AVIATION NEWS March–April 1990

- Kelshall pp.4-24

- Blair pp.503-509&728

- Kelshall pp.26-31,42,47-48&57

- "Patrol info for U-156". Guðmundur Helgason. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Kenshall p.29

- Cressman p.77

- Cressman p.79

- Kelshall pp.26&32

- "Patrol info for U-67". Guðmundur Helgason. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Kelshall pp.26,33,35,43-44&54

- "Patrol info for U-502". Guðmundur Helgason. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Cressman p.78

- Kelshall pp.26,35-42,44,49-51,60-64&67

- "Patrol info for U-161". Guðmundur Helgason. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Cressman p.76

- Cressman pp.77-78

- Kelshall p.59

- Kelshall p.66

- Blair p.508

- Kelshall pp.45&56

- Blair p.507

- Kelshall p.55

- "Patrol info for U-129". Guðmundur Helgason. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Kelshall p.47

- Kelshall p.53

- Kelshall p.57

- Cressman p.80

- Kelshall p.56

- "Leonardo da Vinci" at regiamarina.net, Cristiano D'Adamo; retrieved 25 July 2019

- Kelshall p.52

- "Patrol info for U-126". Guðmundur Helgason. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Cressman p.81

- Kelshall p.60

- Cressman p.82

- Enrico Tazzoli at regiamarina.net, Cristiano D'Adamo; retrieved 25 July 2019

- Kelshall pp.58&60

- Guiseppe Finzi at regiamarina.net, Cristiano D'Adamo; retrieved 25 July 2019

- Morosini at regiamarina.net, Cristiano D'Adamo; retrieved 25 July 2019

- Blair pp. 504–505.

- Blair pp. 505–506.

- Kelshall p. 43.

- Blair p. 506.

- Kelshall pp. 58–60.