Operation Sky Shield

Operation Sky Shield, sometimes known as Exercise Skyshield, was a series of three large-scale military exercises conducted in the United States in 1960, 1961, and 1962 by the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) and the Strategic Air Command (SAC) to test defenses against an air attack from the USSR. The tests were intended to ensure that any attacks over the Canada–US border or coastlines would be detected and subsequently stopped.

The operations involved 6,000 sorties flown by aircraft of the United States Air Force, British Royal Air Force (RAF) and Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), simulating Soviet fighter / bomber attacks against New York, Chicago, San Diego, Los Angeles, Washington D.C. and more. This made it among the largest military aviation exercises ever held.

While the United States and Canada assured citizens that its defenses were "99 percent effective,"[1] the results showed how unsuccessful the defense would be against a Soviet air attack. No more than one-fourth of bombers in Sky Shield would have been intercepted according to the reports written after the operations.[2] The results of the tests were classified until 1997 over fears that they could be used by the Soviet Union to engage the US more effectively in the event of a third World War.

In these exercises, all air traffic from the Arctic Circle to Mexico was grounded, sometimes for up to twelve hours. The estimated cost of these shut downs was millions of dollars. In the reporting of the September 11 attacks in 2001, these exercises were often overlooked, with news agencies reporting that the similar, but unplanned, evacuation of US airspace during that incident was the first ever clearing of US airspace of all civilian aircraft.

Operations

Sky Shield I (1960)

In late July 1960, the Department of Defense gave airlines an eight-week notice that it would mobilize an unprecedented number of combat aircraft in a training exercise so vast that it could succeed only if civil aircraft did not interfere and that the airlines should adjust their schedules accordingly and notify their reservation holders.[2] An estimated 1,000 U.S. commercial flights carrying around 37,000 passengers, and 700 general aviation aircraft were affected by this exercise. To go along with this, Canada had 310 flights with 3,000 passengers affected, and 31 foreign flights scheduled to land in North America were canceled.[1] William B. Becker of the Air Transport Association (ATA) wrote that an "Estimated cost figures from only nine of the many air carriers affected totaled approximately one-half million dollars." (equivalent to $4,320,000 in 2019)[2]

Operation Sky Shield took place as planned on September 10, 1960 from 1:00 a.m. to 7:00 a.m. CDT.[1] The operation included 1,129 fighter scrambles which were flown by approximately 360 interceptors against the Strategic Air Command (SAC) strike force of B-47 Stratojets and B-52 Stratofortresses, which simulated an "enemy" (Soviet) force of 310 bombers.[2] This also included an "attack" by eight Royal Air Force (RAF) Vulcan B.2 bombers. Four Vulcans attacked from Scotland and four from Bermuda. The first "casualty" of the exercise was an RAF Vulcan which was intercepted by a McDonnell F-101 Voodoo 56,000 ft (17,000 m) above Goose Bay, Labrador. Despite this, the Vulcans achieved unprecedented survivability with seven of the eight British bombers managing to reach their targets and return to Stephenville, Newfoundland unscathed. Their effectiveness in the exercise was largely due to the advanced electronic countermeasures (ECM) systems on these aircraft (three of the southern route bombers putting up a wall of interference while the fourth made an attack[3]) and the Vulcan's famed and unique maneuverability amongst strategic bombers.[4]

The response after the operation from the FAA and ATA was they would continue to support NORAD. William Becker said "The airlines will continue to cooperate to the fullest extent where military requirements dictate the necessity. In the event that an exercise of the magnitude of Sky Shield is justified in the future, we strongly urge that a minimum of 90 days’ advance notice be given. The exercise should be conducted on Saturday night-Sunday morning of a three-day holiday weekend."[2] The American public also responded well, and when given a reasonable amount of time to reschedule their flights were fully understanding and supportive of the military defense operations.[2] However, John Diefenbaker who was the Canadian prime minister at the time of the operation objected to Sky Shield, and repeatedly shared his objections until Americans called off the operation on September 15.[5]

Sky Shield II (1961)

Planning for Sky Shield II was more organized than the first operation. In August 1961, the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association published an article in its Pilot Magazine saying "Don’t Forget Sky Shield," and "If you’ve planned a flight for Oct. 14 or 15, better look at the clock before you take off."[2] An estimated 2,900 U.S. and Canadian flights, scheduled to carry around 125,000 passengers, were cancelled.[1]

Operation Sky Shield II occurred on October 14, 1961 from 11:00 a.m. to 11:00 p.m.[1] It was one of the largest defense maneuvers ever held in the western world, and involved approximately 250 bombers against 250 missile site and 1,800 fighter planes flying more than 6,000 sorties.[1] More than 50 U.S. fighter-interceptor squadrons participated, including those equipped with McDonnell F-101B Voodoos, Convair F-106 Delta Darts and F-102 Delta Daggers, Lockheed F-104 Starfighters, Northrop F-89J Scorpions, and Douglas F4D Skyrays.[2] Across the continent some 150,000 airfield and flying personnel and 50,000 more in close support would also play a part, spanning NORAD, the U.S. Air Force, Army, Navy, Air National Guard, and the Royal Canadian Air Force.[2] During Sky Shield II, the RAF Vulcans participated again, four from 27 Sqn (serials XJ824, XH555, XJ823, and one other), again flying from Kindley Air Force Base, Bermuda, and four aircraft from 83 Sqn flying from RAF Lossiemouth, in Scotland.[6] They simulated Russian heavy bombers operating at the highest altitude - 56,000 ft (17,000 m); above the United States Air Force (USAF) B-52 Stratofortresses at 35-42,000 ft and the lower level B-47 Stratojets. One 27 Sqn Vulcan, flying from Bermuda, successfully evaded the defending F-102 Delta Dagger interceptors, covered by the other three Vulcans providing jamming, and tracked round to the north, landing at Plattsburgh Air Force Base, New York.[7] The northern force attacking in a stream reported a single instance of radar contact by an interceptor and all four landed in Newfoundland.[8]

Sky Shield II phases were transmitted to Royal Canadian Air Force stations by secure media, but in case of intercept, not the details. Operations were given RCAF code names, and planning conferences included Trusted Agents. Final pre-event checklists were dubbed Double Take A or B. The harried, last moments: Fast Pace. The Go hour: Cocked Pistol. Various milestones were designated Big Noise A or B and so on, through Fade Out.[1]

A B-52 lost in the Atlantic Ocean accounted for the 8 lives lost during the exercise. On 15 October 1961, a search triangle 600 miles from New York was set up looking for the missing crew. A US Coast Guard (USCG) cutter reported seeing an orange flare at 12:15 a.m. on the 17 of October, but the eight crew members were eventually presumed lost at sea. These were the only casualties of the three operations.

General Laurence Kuter was quoted in media after Sky Shield II ranging from Air Force Magazine to the Chicago Tribune, calling Sky Shield II "the greatest exercise in information analysis, decision-making, and action-taking in continental aerospace defense in all our history."[2] But Kuter deflected calls for a score of the operation, reiterating that Sky Shield's intent was, "by no means, a contest between offensive and defensive forces."[2]

After the operation, NORAD produced an exhaustive report, presented it to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and then filed it in secure archives.[2] It wasn't until 1997 that most, but not all, of the Sky Shield results were declassified.[2] Conclusions showed that nearly one-half of enemy flights at low altitude had escaped detection, and of those initially detected, 40 percent then eluded tracking radar by changing their formation shape, size, or altitude. No more than one-fourth of bombers in Sky Shield II would have been intercepted.[2]

Sky Shield III (1962)

Sky Shield III, held on September 2, 1962 from 1:00 p.m. to 6:30 p.m.,[1] was North America's first test of procedures for clearing national civilian air traffic at short notice, such as would be done in the event of a Soviet attack. Hundreds of USAF trainers were used to simulate normal civil traffic levels and routes. The Air Force trainers launched 319 Lockheed T-33 light jets, 263 in the U.S. and 56 in Canada, from random and unannounced locations. As the alert horn sounded, Federal Aviation Administration controllers hustled to get them to civil airports far from the metropolitan targets that were presumed to be under mushroom clouds. All T-33s were on the ground in Canada within 49 minutes, and in the United States within 72 minutes.[2]

The closings this operation were 1,800 scheduled airline flights in the United States, 130 more in Canada, and 31 foreign airlines. The total cost of these closings estimated to be $1 million.[2]

Sky Shield IV

Sky Shield IV was planned for 1963, but the Strategic Air Command (SAC) was against it and instead smaller exercises occurred called Top Rung that began in 1964.[1]

Intelligence gained from all three operations

When the friendly plane units posing as the enemy broke preauthorized flight patterns and attempted to simulate the enemy as much as possible by flying below the preauthorized fly zone and in patterns that also deviated from the initial plans they caused great difficulties to the defenders.[2]

The NORAD remote radar stations that were considered high risk for destruction survived all 3 simulated ground attacks.[2]

The Distant Early Warning and Ballistic Missile Early Warning System lines were often penetrated by enemy cells of up to four aircraft even while flying at the radar's optimal altitude for tracking. NORAD acknowledged that real enemy bombers would fly much lower than the test altitude and be more successful.[2]

The SAGE radar system was able to track less than one-third the total mileage flown within the radar's range. While NORAD had prepared for high tech electronic warfare and countermeasures the low-tech chaff is what affected SAGE the most. SAGE was affected so much that NORAD had to move to manual plane tracking which allowed the enemy to get into bombing range before being tracked.[2]

Media coverage

The penetrations by RAF Vulcans was first reported in a British newspaper, the Daily Express, in January 1963. It was initially strenuously denied by the United States Department of Defense, which stated "that British aircraft last took part in a Strategic Air Command exercise over the United States in the Autumn of 1960." In a later statement, Eugene Zuckert, Secretary of the USAF, said the report was; "completely without foundation." The Chicago Tribune newspaper reported; "We do not know whether the Royal Air Force leaked the story to show up the Kennedy administration because of its decision to scrap the Skybolt air-to-ground missile."[9]

U.S. media reaction to Operation Sky Shield II

On Wednesday, October 11, 1961 The Leader-Herald of Gloversville and Johnstown, N.Y. wrote a front-page article entitled "U.S. Air Defense to Test Muscle in Operation Sky Shield II."[10] This article outlined the North American Air Defense System's (NORAD) plan to simulate missile-less mock war to test the North American's air defense systems for long-range bombers. The article outlined that the exercise was planned to take twelve hours beginning at 1 p.m. on Saturday, October 14 through 1 a.m. Sunday, October 15th. The article continues to outline the exercise in great detail. The Leader-Herald states that the purpose of this exercise is to provide operational training for the entire North American Air Defense System program.[10]

The beginning of this Sky Shield operation was to begin when a force of Strategic Air Command (SAC) B-47's and B-52's accompanied by a number of British bombers initiated contact with NORAD's systems.[10]

The defense system was said to consist of a NORAD fighter squadron composed of both U.S. and Royal Canadian Air Force. This squadron would consist of about 6,000 sorties consisting of F-102, F-106, and F-89 jets.[10]

The NORAD defense coordinator for this operation was General Laurence S. Kuter located in Colorado Springs. In addition, Lt. Gen Robert J. Wood would command the U.S. army air defense units in coordination with Kuter's plans.[10]

The total estimated number of military personnel and civilians was estimated to reach 150,000 with another 100,000 coordinated into rescue teams and maintenance staff on stand-by.[10]

Units involved in Operation Sky Shield II

Fifteen Army National Guardsman Nike-Ajax missile bases in the northeast United States were to remain in stand-by mode, purely as practice because no missiles were to be fired during the exercise.[10]

Thirty Air National Guard interceptor squadrons were planned to patrol along the northern and southern perimeters of the United States as part of the NORAD defense system.[10]

United States Navy Airborne Early Warning Squadrons consisting of WV-2 Super Constellations and Navy picket ships were planned to be the first warning line in the NORAD defense system by being positioned on the outer ring of the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean defense systems. The WV-2's would patrol the northern part of the oceans with their large fuel reserves while the picket ships escorted by destroyers would survey the southern part of the oceans with their long range radar systems.[10]

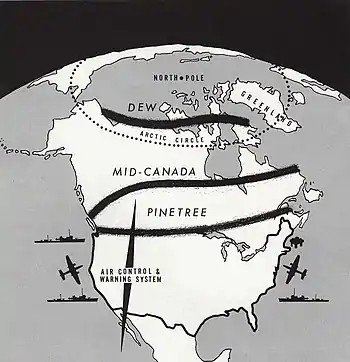

Protecting the Arctic Cap were the Canadians and their radar systems. Their Pinetree Line stations along the Distant Early Warning line, the Mid-Canadian line, and the U.S. border were also coordinating with the NORAD defense system.[10]

While there would be no participation by any planes south of the Mexican border the Aircraft Control and Warning bases located in the Gulf coast were all made aware of the operation and on stand-by.[10]

Effect on civilian air traffic

The estimated 1,880 U.S. civilian domestic and international air fleet were all to remain grounded during Operation Sky Shield II. In addition to the estimated 70,000 general aviation planes also located in the United States. In conformation with the Air Force's Security Control of Air Traffic plan all foreign air carriers would also be grounded from sending planes to the United States.[10]

FAA Administrator Najeeb Halaby commented that the Sky Shield grounding of all civilian air traffic was necessary to allow NORAD and SAC pilots full range of motion at all altitudes. He also noted that the use of radar jamming equipment by the attacking force would severely affect all civilian traffic and make them incapable of using their radar equipment to maneuver and land their planes.[10]

Other unnamed FAA officials commented and stated that there was a possibility of an enemy attack during the operation and that the NORAD defenders would be easily able to identify actual enemy aircraft from other participants in the operation.[10]

Airport activities during the operations

During Operation Sky Shield airports and airlines prepared tours charging around 50 cents for a 20-minute tour.[2] For example, at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) temporary guides met visitors at ticketing posts and showed off the new passenger terminal and ramp. To go along with this, at every gate across the airport different airliners were showing off their latest planes. United Airlines showed off its Douglas DC-8 and Boeing 720 jets, Convair 340, and Douglas DC-7A cargo-liner. Bonanza Air Lines opened its Fairchild F-27; Pacific Air Lines a Martin 4-0-4, and National Airlines a Lockheed Constellation.[2] On the LAX ramp sat Western Airlines’s tiny 1926 Douglas M-2 biplane.[2]

During Operation Sky Shield II airports continued to hold open houses, and many airlines threw parties for their staff. Los Angeles International had 40,000 visitors, while workers took advantage of the closing to install a new air traffic control tower.[2] At San Diego's Lindbergh Field, maintenance workers shut down power and performed 12 hours of repairs in the terminal, and across San Diego at the Mission Valley Inn, Pacific Southwest and American Airlines held a crew luncheon and pool party.[2] At Chicago O’Hare, Eastern Air Lines, American Airlines, and Continental swung open the doors to their Boeing 707s and 720Bs. Trans World Airlines presented its Convair 880, and United Airlines, its new Sud-Aviation Caravelle twin-jet from France. At Chicago's Midway, American, United, and TWA displayed Douglas DC-6s and DC-7s.[2] The two Chicago airports also worked on communications during the down time and reduced the price of phone calls between each other from 15 to 10 cents for the first five minutes.[2]

See also

References

- Notes

- Kriz, Marjorie (1988). "Operation Sky Shield" (PDF).

- ""This Is Only a Test"". Air & Space Magazine. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- Hamilton-Paterson 2010, pp. 157–158.

- Later in service, Vulcans would be flown at treetop level - below 100 ft (30 m) - missions more usually associated with a fighter-bomber.

- Boyko, John (2016). Cold Fire: Kennedy's Northern Front. Knopf Canada. pp. 57–58.

- "Milestones of Flight" 1961." Archived 21 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine RAF Museum. Retrieved: 5 March 2011.

- Vulcan Units of the Cold War Andrew Brookes, Chris Davey p21

- Avro Vulcan, Part 1 RAF Illustrated By Kev Darling p53-54

- "World News." Flight International, 17 January 1963, p. 88.

- Nolan, Tom The Leader-Herald (11 October 1961). "U.S. Air Defense to Test Muscle in Operation Sky Shield II" (PDF). Fulton History. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- Bibliography

- Hamilton-Paterson, James. Empire of the Clouds: When Britain's Aircraft Ruled the World. London: Faber & Faber, 2010. ISBN 978-0-571-24794-3.

- Mola, Roger. "This Is Only a Test." Air & Space, 1 March 2002.