Labrador

Labrador (/ˈlæbrədɔːr/ LAB-rə-dor) is a geographic and cultural region within the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It is the primarily continental portion of the province and constitutes 71% of the province's area but is home to only 6% of the province's population. It is separated from the island of Newfoundland by the Strait of Belle Isle. It is the largest and northernmost geographical region in Atlantic Canada.

Labrador

| |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s): "The Big Land" | |

| Motto(s): | |

| Anthem: Ode to Labrador | |

Labrador  Labrador | |

| Coordinates: 54°20′00″N 61°44′57″W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Newfoundland and Labrador |

| Founded | 1763 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 294,330 km2 (113,640 sq mi) |

| Population (2016) | |

| • Total | 27,197 |

| • Density | 0.092/km2 (0.24/sq mi) |

| Time zones | UTC−4 (AST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−3 (ADT) |

| UTC−3:30 (NST) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−2:30 (NDT) |

| MP | 1 |

| MHA | 4 |

| Ethnic groups | English, Innu, Inuit, Métis |

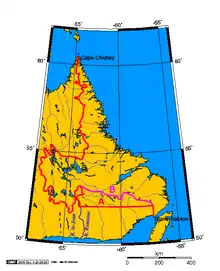

Labrador occupies most of the eastern part of the Labrador Peninsula. It is bordered to the west and the south by the Canadian province of Quebec. Labrador also shares a small land border with the Canadian territory of Nunavut on Killiniq Island.

The aboriginal peoples of Labrador include the Northern Inuit of Nunatsiavut, the Southern Inuit-Métis of NunatuKavut, and the Innu of Nitassinan.[2]

Etymology

Labrador is named after João Fernandes Lavrador, a Portuguese explorer who sailed along the coasts of the Peninsula in 1498–99. Lavrador in Portuguese means "farmer".

Geography

Labrador has a roughly triangular shape that encompasses the easternmost section of the Canadian Shield, a sweeping geographical region of thin soil and abundant mineral resources. Its western border with Quebec is the drainage divide of the Labrador Peninsula. Lands that drain into the Atlantic Ocean are part of Labrador, while lands that drain into Hudson Bay are part of Quebec. Northern Labrador's climate is classified as polar, while Southern Labrador's climate is classified as subarctic.

Labrador can be divided into four geographical regions: the North Coast, Central Labrador, Western Labrador, and the South Coast. Each of those regions is described below.

North Coast

From Cape Chidley to Hamilton Inlet, the long, thin, northern tip of Labrador holds the Torngat Mountains, named after an Inuit spirit believed to inhabit them. The mountains stretch along the coast from Port Manvers to Cape Chidley, the northernmost point of Labrador. The Torngat Mountain range is also home to Mount Caubvick, the highest point in the province. This area is predominantly Inuit, with the exception of a small Innu community, Natuashish. The North Coast is the most isolated region of Labrador, with snowmobiles, boats, and planes being the only modern modes of transportation. The largest community in this region is Nain.

Nunatsiavut

Nunatsiavut is an Inuit self-government region in Labrador created on June 23, 2000. The Settlement area comprises the majority of Labrador's North Coast, while the land-use area also includes land farther to the interior and in Central Labrador. Nain is the administrative centre.

Central Labrador

Central Labrador extends from the shores of Lake Melville into the interior. It contains the Churchill River, the largest river in Labrador and one of the largest in Canada. The hydroelectric dam at Churchill Falls is the second-largest underground power station in the world. Most of the supply is bought by Hydro-Québec under a long-term contract. The Lower Churchill Project will develop the remaining potential of the river and supply it to provincial consumers. Known as "the heart of the Big Land", the area's population comprises people from all groups and regions of Labrador.

Central Labrador is also home to Happy Valley – Goose Bay. Once a refuelling point for plane convoys to Europe during World War II, CFB Goose Bay is now operated as a NATO tactical flight training site. It was an alternate landing zone for the United States' Space Shuttle. Other major communities in the area are North West River and the large reserve known as Sheshatshiu.

Western Labrador

The highlands above the Churchill Falls were once an ancient hunting ground for the Innu First Nations and settled trappers of Labrador. After the construction of the hydroelectric dam at Churchill Falls in 1970, the Smallwood Reservoir has flooded much of the old hunting land—submerging several grave sites and trapping cabins in the process.

Western Labrador is also home to the Iron Ore Company of Canada, which operates a large iron ore mine in Labrador City. Together with the small community of Wabush, the two towns are known as "Labrador West".

NunatuKavut

From Hamilton Inlet to Cape St. Charles/St. Lewis, NunatuKavut is the territory of the NunatuKavummiut or Central-Southern Labrador Inuit (formerly known as the Labrador Métis). It includes portions of Central and Western Labrador, but more NunatuKavummiut reside in its South Coast portion: it is peppered with tiny Inuit fishing communities, of which Cartwright is the largest.

The Labrador Straits

From Cape Charles to the Quebec/Labrador coastal border, the Straits is known for its Labrador sea grass (as is NunatuKavut) and the multitude of icebergs that pass by the coast via the Labrador Current.

Red Bay is known as one of the best examples of a preserved 16th-century Basque whaling station. It is also the location of four 16th-century Spanish galleons. The lighthouse at Point Amour is the second-largest lighthouse in Canada. MV Kamutik, a passenger ferry between the mainland and St. Barbe on the island of Newfoundland, is based in Blanc Sablon, Quebec, near the Labrador border. L'Anse-au-Loup is the largest town on the Labrador Straits. L'Anse-au-Clair is a small town on the Labrador side of the border.

Time zones of Labrador

Most of Labrador (from Cartwright north and west) uses Atlantic Time (UTC−4 in winter, UTC−3 in summer). The south eastern tip nearest Newfoundland uses Newfoundland Time (UTC−3:30 in winter, UTC−2:30 in summer) to stay co-ordinated with the more populous part of the province.

Climate of Labrador

Most of Labrador has a subarctic climate (Dfc), but northern Labrador has a tundra climate (ET) and Happy Valley - Goose Bay has a humid continental (Dfb) microclimate. Summers are typically cool to mild across Labrador and very rainy, and usually last from late June to the end of August. Autumn is generally short, lasting only a couple of weeks and is typically cool and cloudy. Winters are long, cold, and extremely snowy, due to the Icelandic Low. Springtime most years does not arrive until late April, with the last snow fall usually falling during early June. Labrador is a very cloudy place, with sunshine levels staying relatively low during spring and summer due to the amount of rain and clouds, before sharply dropping off during September as winter draws nearer.

History

Early history

Early settlement in Labrador was tied to the sea as demonstrated by the Montagnais (or Innu) and Inuit, although these peoples also made significant forays throughout the interior.

It is believed that the Norsemen were the first Europeans to sight Labrador around 1000 AD, but no Norse remains have been found on the North American mainland. The area was known as Markland in Greenlandic Norse and its inhabitants were known as the Skræling.

In 1499 and 1500, the Portuguese explorers João Fernandes Lavrador and Pro de Barcelos reached what was probably now Labrador, which is believed to be the origin of its name.[3] Maggiolo's World Map, 1511, shows a solid Eurasian continent running from Scandinavia around the North Pole, including Asia's arctic coast, to Newfoundland-Labrador and Greenland. On the extreme northeast promontory of North America, Maggiolo place-names include Terra de los Ingres (Land of the English), and Terra de Lavorador de rey de portugall (Land of Lavrador of the King of Portugal). Further south, we notice Terra de corte real e de rey de portugall (Land of "Corte-Real" and of the King of Portugal) and terra de pescaria (Land for Fishing). In the 1532 Wolfenbüttel map, believed to be the work of Diogo Ribeiro, along the coast of Greenland, the following legend was added: As he who first sighted it was a farmer from the Azores Islands, this name remains attached to that country. This is believed to be João Fernandes. For the first seven decades or so of the sixteenth century, the name Labrador was sometimes also applied to what we know as Greenland.[4] Labrador ("lavrador" in Portuguese) means husbandman or farmer of a tract of land (from "labour" in Latin) —the land of the labourer. European settlement was largely concentrated in coastal communities, particularly those south of St. Lewis and Cape Charles, and are among Canada's oldest European settlements.

In 1542 Basque mariners came ashore at a natural harbour on the northeast coast of the Strait of Belle Isle. They gave this "new land" its Latin name Terranova. A whaling station was set up around the bay, which they called Butus and is now named Red Bay after the red terracotta roof tiles they brought with them. A whaling ship, the San Juan, sank there in 1565 and was raised in 1978.[5]

The Moravian Brethren of Herrnhut, Saxony, first came to the Labrador Coast in 1760 to minister to the migratory Inuit tribes there. They founded Nain, Okak, Hebron, Hopedale and Makkovik. Quite poor, both European and First Nations settlements along coastal Labrador came to benefit from cargo and relief vessels that were operated as part of the Grenfell Mission (see Wilfred Grenfell). Throughout the 20th century, coastal freighters and ferries operated initially by the Newfoundland Railway and later Canadian National Railway/CN Marine/Marine Atlantic became a critical lifeline for communities on the coast, which for the majority of that century did not have any road connection with the rest of North America.

Labrador was within New France mostly by 1748. However, the Treaty of Paris (1763) that ended the French and Indian War transferred New France (including Labrador though excluding the islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon southwest of Newfoundland) to the British, which administered the area as the Province of Quebec until splitting it in two in 1791, with Labrador located in Lower Canada. However, in 1809 the British Imperial government detached Labrador from Lower Canada for transfer to the separate, self-governing Newfoundland Colony.

20th century

As part of Newfoundland since 1809, Labrador was still being disputed by Quebec until the British resolved their border in 1927. In 1949, Newfoundland entered into confederation, becoming part of Canada (see above articles for full information).

Labrador played strategic roles during both World War II and the Cold War. In October 1943, a German U-boat crew installed an automated weather station on the northern tip of Labrador near Cape Chidley, code-named Weather Station Kurt; the installation of the equipment was the only-known armed German military operation on the North American mainland during the war. The station broadcast weather observations to the German navy for only a few days, but was not discovered until the 1980s when a historian, working with the Canadian Coast Guard, identified its location and mounted an expedition to recover it. The station is now exhibited in the Canadian War Museum.[6]

The Canadian government built a major air force base at Goose Bay, at the head of Lake Melville during the Second World War, a site selected because of its topography, access to the sea, defensible location, and minimal fog. During the Second World War and the Cold War, the base was also home to American, British, and later German, Dutch, and Italian detachments. Today, Serco, the company contracted to operate CFB Goose Bay is one of the largest employers for the community of Happy Valley-Goose Bay.

Additionally, both the Royal Canadian Air Force and United States Air Force built and operated a number of radar stations along coastal Labrador as part of the Pinetree Line, Mid-Canada Line and DEW Line systems. Today the remaining stations are automated as part of the North Warning System, however the military settlements during the early part of the Cold War surrounding these stations have largely continued as local Innu and Inuit populations have clustered near their port and airfield facilities.

During the first half of the 20th century, some of the largest iron ore deposits in the world were discovered in the western part of Labrador and adjacent areas of Quebec. Deposits at Mont Wright, Schefferville, Labrador City, and Wabush drove industrial development and human settlement in the area during the second half of the 20th century.

The present community of Labrador West is entirely a result of the iron ore mining activities in the region. The Iron Ore Company of Canada operates the Quebec North Shore and Labrador Railway to transport ore concentrate 578 kilometres (359 miles) south to the port of Sept-Îles, Quebec, for shipment to steel mills in North America and elsewhere.

During the 1960s, the Churchill River (Labrador name: Grand River) was diverted at Churchill Falls, resulting in the flooding of an enormous area – today named the Smallwood Reservoir after Joey Smallwood, the first premier of Newfoundland. The flooding of the reservoir destroyed large areas of habitat for the threatened Woodland Caribou. A hydroelectric generating station was built in Labrador and a transmission line to the neighbouring province of Quebec.

Construction of a large hydroelectric dam project at Muskrat Falls began in 2012 by Nalcor Energy and the Province of Newfoundland. Muskrat Falls is 45 km (30 miles) west of Happy Valley-Goose Bay on the Grand River (Newfoundland name: Churchill River). A transmission line began construction in October 2014 and was completed in 2016 that will deliver power down to the southern tip of Labrador and underwater across the strait of Belle Isle to the Province of Newfoundland in 2018.[7]

From the 1970s to early 2000s, the Trans-Labrador Highway was built in stages to connect various inland communities with the North American highway network at Mont Wright, Quebec (which in turn is connected by a highway running north from Baie-Comeau, Quebec). A southern extension of this highway has opened in stages during the early 2000s and is resulting in significant changes to the coastal ferry system in the Strait of Belle Isle and southeastern Labrador. These "highways" are so called only because of their importance to the region; they would be better described as roads, and are not completely paved.

A study on a fixed link to Newfoundland, in 2004, recommended that a tunnel under the Strait of Belle Isle, being a single railway that would carry cars, buses and trucks, was technologically the best option for such a link. However, the study also concluded that a fixed link was not economically viable. Conceivably, if built with federal aid, the 1949 terms of union would be amended to remove ferry service from Nova Scotia to Port aux Basques across the Cabot Strait.

Although a highway link has, as of 16 December 2009, been completed across Labrador, this route is somewhat longer than a proposed Quebec North Shore highway that presently does not exist. Part of the "highway", Route 389, starting approximately 212 kilometres (132 mi) from Baie-Comeau to 482 kilometres (300 mi), is of an inferior alignment, and from there to 570 kilometres (350 mi), the provincial border, is an accident-prone section notorious for its poor surface and sharp curves. Quebec in April 2009 announced major upgrades to Route 389 to be carried out.

Route 389 and the Trans-Labrador Highway were added to Canada's National Highway System in September 2005.

Labrador constitutes a federal electoral district electing one member to the House of Commons of Canada. Due to its size, distinct nature, and large Aboriginal population, Labrador has one seat despite having the smallest population of any electoral district in Canada. Formerly, Labrador was part of a riding that included part of the Island of Newfoundland. Labrador is divided into four provincial electoral districts in the Newfoundland and Labrador House of Assembly.

Boundary dispute

| Labrador Boundary Dispute | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Court | Judicial Committee of the Privy Council |

| Full case name | IN THE MATTER OF THE BOUNDARY BETWEEN THE DOMINION OF CANADA AND THE COLONY OF NEWFOUNDLAND IN THE LABRADOR PENINSULA |

| Decided | 1 March 1927 |

| Citation(s) | [1927] UKPC 25, [1927] A.C. 695 |

| Transcript(s) | |

| Case history | |

| Appealed from | Supreme Court of Canada, Supreme Court of Newfoundland |

| Court membership | |

| Judges sitting | Viscount Haldane, Lord Finlay, Lord Sumner, Lord Warrington of Clyffe |

| Case opinions | |

| Decision by | Viscount Haldane |

| Keywords | |

| Labrador boundary | |

The border between Labrador and Canada was set on 1 March 1927, after a five-year trial. In 1809 Labrador had been transferred from Lower Canada to Newfoundland Colony but the inland boundary of Labrador had never been precisely stated.[8] Newfoundland argued it extended to the height of land, while Canada, stressing the historical use of the term "Coasts of Labrador", argued the boundary was 1 statute mile (1.6 km) inland from the high-tide mark. As Canada and Newfoundland were separate Dominions, but both within the British Empire, the matter was referred to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council[9] (in London). Their decision set the Labrador boundary mostly along the coastal watershed, with part being defined by the 52nd parallel north. One of Newfoundland's conditions for joining Confederation in 1949 was that this boundary be entrenched in the Canadian constitution.[9] While this border has not been formally accepted by the Quebec government, the Henri Dorion Commission (Commission d'étude sur l'intégrité du territoire du Québec) concluded in the early 1970s that Quebec no longer has a legal claim to Labrador.[10]

Prior to the 1995 Quebec sovereignty referendum, Parti Québécois Premier Jacques Parizeau indicated that, in the event of a "yes" vote, a sovereign Quebec under his leadership would recognise the 1927 border. However, in 2001, Parti Québécois cabinet ministers Jacques Brassard and Joseph Facal reasserted that Québec has never recognised the 1927 border:

Les ministres rappellent qu'aucun gouvernement québécois n'a reconnu formellement le tracé de la frontière entre le Québec et Terre-Neuve dans la péninsule du Labrador selon l'avis rendu par le comité judiciaire du Conseil privé de Londres en 1927. Pour le Québec, cette frontière n'a donc jamais été définitivement arrêtée.[11]

[The ministers reiterate that no Quebec government has ever formally recognised the drawing of the border between Quebec and Newfoundland in the Labrador peninsula according to the opinion rendered by the London Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in 1927. For Quebec, this border has thus never been definitively defined.]

Self-government

A Royal Commission in 2002 determined that there is some public pressure from Labradorians to break from Newfoundland and become a separate province or territory.

Indigenous self-government

Some of the Innu nation would have the area become a homeland for them, much as Nunavut is for the Inuit, as a good portion of Nitassinan falls within Labrador's borders; a 1999 resolution of the Assembly of First Nations claimed Labrador as a homeland for the Innu and demanded recognition in any further constitutional negotiations regarding the region.[12]

The northern Inuit self-government region of Nunatsiavut was created in 2005[13] through agreements with the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador and the Government of Canada.

The Southern Inuit of NunatuKavut, who are also seeking self-government, have their land claim before the Government of Canada. The Government of Newfoundland and Labrador refuses to recognise or negotiate with the Inuit of NunatuKavut until their claim has been accepted by the Government of Canada.[14]

Timeline

- 11th century: Probably visited by Leif Ericson. See Markland.

- 1498: Sighted by João Fernandes Lavrador, who gave "Labrador" its name.

- 1498: Visited by John Cabot.

- 1500: Visited by Gaspar Corte-Real.

- 1534: Visited by Jacques Cartier.

- 1763: Labrador is transferred from the French to the British as per the Treaty of Paris.

- 1774: Labrador is transferred (along with Anticosti Island and the Magdalen Islands) to the Province of Quebec.

- 1791: Labrador becomes part of Lower Canada when Quebec is divided into two colonies.

- 1792: George Cartwright publishes his Journal of Transactions and Events, During a Residence of Nearly Sixteen Years on the Coast of Labrador.

- 1809: Labrador (from Cape Chidley to the mouth of the Saint-Jean River) is transferred back to Newfoundland.

- 1825: The north shore of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence west of Blanc-Sablon, Quebec, and south of 52° north is separated from Labrador and transferred back to Lower Canada.

- 1927: Labrador boundary with Quebec determined by arbitration decision of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council of London. The Labrador boundary dispute is settled.

- 1941: Canada builds the air base at Goose Bay.

- 1949: Labrador becomes part of Canada when Newfoundland joins Confederation.

- 2001: The province officially changes its name to Newfoundland and Labrador by a constitutional amendment.

- 2007: The province and Federal Government of Canada sign an agreement to establish Nunatsiavut.

Demographics

| Town | 2016[15] |

|---|---|

| Happy Valley – Goose Bay | 8,109 |

| Labrador City | 7,220 |

| Wabush | 1,906 |

| Nunainguk | 1,125 |

| Sheshatshiu | 1,023 |

| Natuashish | 925 |

| L'Anse-au-Loup | 558 |

| Churchill Falls | 705 |

| Cartwright | 427 |

| Agvituk | 574 |

| North West River | 547 |

| Port Hope Simpson | 412 |

| Forteau | 409 |

| Maggovik | 377 |

| Mary's Harbour | 341 |

| Red Bay | 169 |

| Tikigâksuagusik | 305 |

| Charlottetown | 290 |

| L'Anse au Clair | 216 |

| St. Lewis | 194 |

| KipukKak | 177 |

| Black Tickle | 150 |

| West St. Modeste | 111 |

| Pinware | 88 |

| Lodge Bay | 65 |

| Pinsent's Arm | 65 |

| Mud Lake | 50 |

| Capstan Island | 41 |

| Norman's Bay | 25 |

| Paradise River | 10 |

| Factor | Labrador | Canada |

|---|---|---|

| Male/Female split | 50.7/49.3% | 49.0/51.0% |

| Median age | 38 CD10 /28 CD11 | 39.5 |

| Aboriginal pop. | 22% | 3.8% |

| Non-immigrant pop. | 95.8% | 78.3% |

| Median family income | 171k$ CD10 /47k$ CD11 | 61k$ |

| Unemployment rate | 11.3% | 6.6% |

(CD10, CD11 refer to Census Divisions)

According to the 2011 Census, Labrador was 55.1% White, 18.5% Inuit, 15.6% Metis, and 8.6% First Nations (Innu).

Natural features

Labrador is home to a number of flora and fauna species. Most of the Upper Canadian and Lower Hudsonian mammalian species are found in Labrador.[17] Notably the Polar bear, Ursus maritimus, reaches the southeast of Labrador on its seasonal movements.[18]

References

- "Labrador Nunatsuak: Stories of the Big Land". Archived from the original on 2017-09-12. Retrieved 2017-07-04.

- Wadden, Marie (December 1991). Nitassinan: The Innu Struggle to Reclaim Their Homeland. Douglas & McIntyre. p. 240. ISBN 978-1-55365-731-6. Archived from the original on 2013-01-21. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- Bailey W. Diffie and George D. Winius (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese empire. University of Minnesota Press. p. 464. ISBN 0-8166-0782-6. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- See Williamson, James A. (1962). The Cabot Voyages and Bristol Discovery under Henry VII. London. pp. 98, 120–1, 312–17. OCLC 808696.

- Richardson, Nigel (1 June 2015). "A corner of Canada that is forever Basque". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- "Weather station Kurt erected in Labrador in 1943". Retrieved 2010-02-18.

- http://muskratfalls.nalcorenergy.com/team-work-and-dedication-brings-the-link-to-completion/

- "Labrador-Canada boundary". marianopolis. 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

Labrador Act, 1809. – An imperial act (49 Geo. III, cap. 27), 1809, provided for the re-annexation to Newfoundland of 'such parts of the coast of Labrador from the River St John to Hudson's Streights, and the said Island of Anticosti, and all other smaller islands so annexed to the Government of Newfoundland by the said Proclamation of the seventh day of October one thousand seven hundred and sixty-three (except the said Islands of Madelaine) shall be separated from the said Government of Lower Canada, and be again re-annexed to the Government of Newfoundland.'

- Frank Jacobs (July 10, 2012). "Oh, (No) Canada!". Opinionator: Borderlines. The New York Times. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- "Henri Dorion debunks the Ten Great Myths about the Labrador boundary". Quebec National Assembly, First Session, 34th Legislature. October 17, 1991. Archived from the original on October 26, 2009. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- Brassard, Jacques & Facal, Joseph (October 31, 2001). "Le ministre des Ressources naturelles du Québec et le ministre délégué aux Affaires intergouvernementales canadiennes expriment la position du Québec relativement à la modification de la désignation constitutionnelle de Terre-Neuve". saic.gouv.qc.ca (Communiqué) (in French). Gouvernement du Québec. Archived from the original on April 28, 2005. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- "Resolution No. 11 – Innu Traditional Territory". Assembly of First Nations Resolutions 1999. Assembly of First Nations. July 20–23, 1999. Archived from the original on August 10, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- "Labrador Inuit land claim passes last hurdle". CBC News. 24 June 2005. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- "Government of Newfoundland Consultation Policy" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-04-06.

- https://stats.gov.nl.ca/Statistics/Topics/census2016/PDF/CCS_Community_2016.pdf

- "2014 Census release topics". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2014-09-06.

- The American Naturalist (1898) Essex Institute, American Society of Naturalists

- C. Michael Hogan (2008) Polar Bear: Ursus maritimus, Globaltwitcher.com, ed. N. Stromberg

Further reading

- Low, Albert Peter (1896), "Report on explorations in the Labrador peninsula along the East Main, Koksoak, Hamilton, Manicuagan and portions of other rivers in 1892–93–94–95", Geological Survey of Canada, Ottawa: Queen's Printer, retrieved 2010-09-13

- The Lure of the Labrador Wild, by Dillon Wallace (1905)

- Along the Labrador Coast, by Charles W. Townsend, M.D. (1907)

- Birds of Labrador, by Charles W. Townsend, M.D. (1907)

- A Labrador Spring, by Charles W. Townsend, M.D. (1910)

- Captain Cartwright and His Labrador Journal, by Charles W. Townsend, M.D. (1911)

- In Audubon's Labrador, by Charles W. Townsend, M.D. (1918)

- Labrador, by Robert Stewart (1977)

- Labrador by Choice, by Benjamin W. Powell, Sr., C.M. (1979)

- The Story of Labrador, by B. Rompkey (2005)

- Buckle, Francis. The Anglican Church in Labrador. (Labrador City: Archdeaconry of Labrador, 1998.)

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Labrador. |

| Look up labrador in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Labrador. |

- Project Gutenberg e-text of Dillon Wallace's The Lure of the Labrador Wild

- Trans-Labrador Highway website – detailed information about traveling in Labrador.