Oral medicine

Oral Medicine is defined by the American Academy of Oral Medicine as the discipline of dentistry concerned with the oral health care of medically complex patients – including the diagnosis and management of medical conditions that affect the oral and maxillofacial region.

An oral medicine doctor has received additional specialized training and experience in the diagnosis and management of oral mucosal abnormalities (growths, ulcers, infection, allergies, immune-mediated and autoimmune disorders) including oral cancer, salivary gland disorders, temporomandibular disorders (e.g.: problems with the TMJ) and facial pain (due to musculoskeletal or neurologic conditions), taste and smell disorders; and recognition of the oral manifestations of systemic and infectious diseases. It lies at the interface between medicine and dentistry. An oral medicine doctor is trained to diagnose and manage patients with disorders of the orofacial region, essentially as a "physician of the mouth."

It represents an emerging specialty of Dentistry. On March 2, 2020, Oral Medicine became the 11th ADA recognized dental specialty.

The specialty is defined within Europe under Directive 2001/19/EC.

History

The importance of the mouth in medicine has been recognized since the earliest known medical writings. For example, Hippocrates, Galen and others considered the tongue to be a "barometer" of health, and emphasized the diagnostic and prognostic importance of the tongue.[1] However, oral medicine as a specialization is a relatively new subject area.[2]:2 It used to be termed "stomatology" (-stomato- + -ology).[2]:1 In some institutions, it is termed "oral medicine and oral diagnosis".[2]:1 American physician and dentist, Thomas E Bond authored the first book on oral and maxillofacial pathology in 1848, entitled "A Practical Treatise on Dental Medicine".[2]:2[3] The term "oral medicine" was not used again until 1868.[3] Jonathan Hutchinson is also considered the father of oral medicine by some.[2]:2 Oral medicine grew from a group of New York dentists (primarily periodontists), who were interested in the interactions between medicine and dentistry in the 1940s.[4] Before becoming its own specialty in the United States, oral medicine was historically once a subset of the specialty of periodontics, with many periodontists achieving board certification in oral medicine as well as periodontics.

Scope

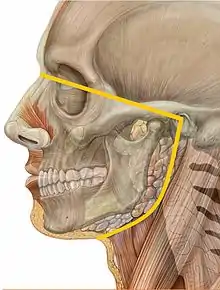

Oral medicine is concerned with clinical diagnosis and non-surgical management of non-dental pathologies affecting the orofacial region (the mouth and the lower face).

Many systemic diseases have signs or symptoms that manifest in the orofacial region. Pathologically, the mouth may be afflicted by many cutaneous and gastrointestinal conditions. There is also the unique situation of hard tissues penetrating the epithelial continuity (hair and nails are intra-epithelial tissues). The biofilm that covers teeth therefore causes unique pathologic entities known as plaque-induced diseases.

Example conditions that oral medicine is concerned with are lichen planus, Behçet's disease and pemphigus vulgaris. Moreover, it involves the diagnosis and follow-up of pre-malignant lesions of the oral cavity, such as leukoplakias or erythroplakias and of chronic and acute pain conditions such as paroxysmal neuralgias, continuous neuralgias, myofascial pain, atypical facial pain, autonomic cephalalgias, headaches and migraines. Another aspect of the field is managing the dental and oral condition of medically compromised patients such as cancer patients suffering from related oral mucositis, bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws or oral pathology related to radiation therapy. Additionally, it is involved in the diagnosis and management of dry mouth conditions (such as Sjögren's syndrome) and non-dental chronic orofacial pain, such as burning mouth syndrome, trigeminal neuralgia and temporomandibular joint disorder.

Lumps and swellings of the mouth

Types of lumps and swelling

It is not uncommon for an individual to experience a lump/swelling in the oral environment. The overall presentation is highly variable and the progression of these lesions can also differ, for example: development of a lesion into a bulla or a malignant neoplasm. Lumps and swellings can occur due to a variety of conditions, both benign and malignant such as:

- Normal variation lesions

- Pterygoid hamulus: This is a hook-shaped structure protruding postero-laterally from the inferior boundary of the medial plate of the pterygoid process

- Parotid papillae: This is the exiting duct from the parotid gland which is commonly found adjacent to the upper second molar on the buccal mucosa

- Lingual papillae: Seen covering the dorsum of the tongue

- Inflammatory

- Abscess: An abscess is a painful collection of pus, usually caused by a bacterial infection

- Cellulitis: Commonly due to a bacterial infection spreading to the deeper layers of the skin leading to a multitude of complications

- Cysts: A cyst is an epithelial lined sac of tissue that has either fluid or semi-fluid content inside

- Sialadenitis: Infection of the salivary glands

- Pyogenic granuloma: Is a relatively common, tumor-like, exuberant tissue response to localized irritation or trauma[6]

- Chornic granulomatous disorders

- Orofacial granulomatosis: This is an uncommon condition but is seen to be increasing in prevalence. This condition presents with facial/labial swellings commonly accompanied with angular stomatitis or cracked lips, ulcers, mucosal tags, cobblestone mucosea or gingival swellings

- Crohn's disease: This is a disease affecting the bowel but commonly has oral lesions associated. Examples of some oral presentations are: raised gingival lesions, hyperplastic folds/cobble-stone mucosa, ulcers, facial swelling and/or angular cheilitis

- Sarcoidosis: Sarcoidosis is a multi-system condition which may lead to gingival enlargement or salivary gland swelling which may result in xerostomia

- Developmental[7]

- Unerupted teeth

- Odontogenic cysts

- Eruption cysts

- Haemangioma

- Lymphangioma

- Palatal tori and mandibular tori: formation of new bone upon the surface of a present bone

- Lingual thyroid: this is an abnormal mass of ectopic thyroid tissue seen at the base of tongue

- Traumatic

- Denture-induced hyperplasia

- Epulis

- Fibroepithelial polyp

- Haematoma

- Mucocele

- Surgical emphysema

- Hormonal

- Pregenancy epulis

- Oral contraceptive pill gingivitis

- Metabolic

- Drugs

- Phenytoin

- Calcium channel blockers

- Ciclosporin

- Allergy

- Infective

- Fibro-osseous

- Neoplasms

- Carcinoma

- Leukeamia

- Lymphoma

- Myeloma

- Odontogenic tumours

- Minor salivary gland tumours

So as seen above the list is extensive and by no means is this a complete and comprehensive representation of all the possible lumps/swellings that can occur in the mouth as to the means of acquiring a swelling in the mouth. When considering what a lump might be caused by the site of which it has appeared can be of significance. Below are some examples of swellings/lumps which usually are present as specific locations in the oral cavity:[8]

- Gingiva

- Congenital hyperplasia

- Abscesses

- Pyogenic granuloma

- Neoplastic

- Pregnancy epulis

- Drug-induced hyperplasia

- Angioedema

- Papilloma/warts

- Palate

- Torus palatinus

- Abscesses

- Unerupted teeth

- Pleomorphic adenomas/salivary neoplasms

- Invasive carcinoma from maxillary sinus

- Kaposi’s sarcoma

- Developmental swellings associated with Paget’s disease

- FOM

- Tongue and buccal mucosa

- Congenital haemangioma

- Congenital macroglossia

- Mucocele

- Vesiculobullous lesions

- Ulcers

- Hyperplasia

Diagnosis of the cause of a lump or swelling

If there is any suspect or unknown reason as to why a lump has arisen In an individuals mouth it is important to establish when this first was noticed and the accompanied symptoms if any. On examination ensure that there is not an obvious cause to the swelling/lump via a thorough: medical, social, dental and family history, followed by an oral examination. Whilst examining the suspected lesion there are some diagnostic aids to note which can be used to formulate a provisional diagnosis.[9] There are many factors taken into consideration in this diagnosis, such as:

- The anatomical position & symmetry

- Midline associated lesions tend to be of a developmental origin (e.g. torus palatinus)

- Bilateral lesions tend to be benign (e.g. sialosis, diabetes etc)

- Consider associations with surrounding anatomical structures

- Malignant lesions are usually unilateral

- Size and shape

- Diagrams or photographs are usually recorded alongside the actual measurement of the lesion

- Colour

- Temperature

- If the lesion is warm it is thought an inflammatory cause is most likely (e.g. abscess or haemangioma)

- Tenderness

- If a lesion is significantly tender on palpation the origin is usually thought to be inflammatory

- Discharge

- Are there any secretions associated with the lesion upon palpation or spontaneously occurring

- Movement

- The lesion should be tested to determine whether it is attached to adjacent structures or the overlying mucosa

- Consistency

- Carcinoma is usually suggested by a hard/indurated consistency

- If a lesion is palpated and a crackling, ‘egg shell’ sound occurs this tends to be a swelling overlying a bony cyst

- Surface texture

- Abnormal vascular changes suggests neoplasm

- Malignant lesions tend to be nodular and may ulcerate

- Papillomas are usually comparative to a wart-like appearance

- Ulceration

- Squamous cell carcinoma is an example of a malignancy which can present with superficial ulceration

- Margin

- Malignant lesions tend to have an ill defined margin

- Benign lesions tend to have a clearly defined margin

- Number of lesions

- Multiple lesions might suggest an infective or developmental aetiology

Investigations

Once the surrounding tissues and the immediate management of any lumps/swellings are taken care of, an Image of the full extent of the lesion is needed. This is done to establish what the lump/swelling is associated with and to ensure that any damaging probablitiy is kept to a minimum. There are a variety of imaging technique options which are chosen based on the lesion: size, location, growth pattern etc. Some examples of images used are: DPT, Scintigraphy, Sialography, Computed Tomography, Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Ultrasound.

As described some lumps or swellings can be in close relation to anatomical structures. Commonly, Teeth are associated in a lesion which brings about the question – “are they still vital?” In order to clarify, any tooth that is associated with a lump or swelling is vitality tested, examined for any pathology or restorative deficiencies in order to determine the long term prognosis of this tooth and how this might affect treatment of the lump/swelling at hand.

Alongside any radiographs wchih may be justified, Blood tests may be needed in order to obtain a definitive diagnosis if there is a suspicion of potential blood dyscrasias or any endocrinopathy involvement.

Finally, a particularly vital means of diagnosis is a biopsy. These tend to be regularly done in the cases of singular, chronic lesions and are carried out in an urgent manner as lesions of this category have a significant malignant potential. The indications to carry out a biopsy include:

- Lesions that have neoplastic or premalignant features or are enlarging

- Persistent lesions that are of uncertain aetiology

- Persistent lesions that are failing to respond to treatment

Once a small piece of tissue is removed for the biopsy, it is then microscopically histopathologically examined.[9]

Training and practice

Australia

Australian programs are accredited by the Australian Dental Council (ADC). They are three years in length and culminate with either a master's degree (MDS) or a Doctor of Clinical Dentistry degree (DClinDent). Fellowship can then be obtained with the Royal Australasian College of Dental Surgeons, FRACDS (Oral Med) and or the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia, FRCP.

Canada

Canadian programs are accredited by the Canadian Commission on Dental Accreditation (CDAC). They are a minimum of three years in length and usually culminate with a master's (MSc) degree. Currently, only the University of Toronto, the University of Alberta, and the University of British Columbia offer programs leading to the specialty. Most residents combine oral medicine programs with oral and maxillofacial pathology programs leading to a dual specialty. Graduates are then eligible to sit for the Fellowship exams with the Royal College of Dentists of Canada (FRCD(C)).

India

Indian programs are accredited by the Dental Council of India (DCI).Oral Medicine is in conjunction with oral radiology in India and it is taught in both graduate and post graduate levels as Oral Medicine and Radiology.They are three years in length and culminate with a master's degree (MDS) in Oral Medicine and Radiology.

New Zealand

New Zealand has traditionally followed the UK system of dual training (dentistry and medicine) as a requisite for specialty practice; the University of Otago Faculty of Dentistry currently offers a 5-year intercalated clinical doctorate/medical degree (DClinDent/MBChB) program. On 9 July 2013, the dental council of New Zealand proposed that the prescribed qualifications for oral medicine be changed to include the new DClinDent in addition to a medical degree, with no requirement for a standard dental degree.[10]

United Kingdom

In the UK, oral medicine is one of the 13 specialties of dentistry recognized by the General Dental Council (GDC).[11] The GDC defines oral medicine as: "[concerned with] oral health care of patients with chronic recurrent and medically related disorders of the mouth and with their diagnosis and non-surgical management."[12] Unlike many other countries, oral medicine physicians in the UK do not usually partake in the dental management of their patients. Some UK oral medicine specialists have dual qualification with both medical and dental degrees.[13] However, in 2010 the GDC approved a new curriculum for oral medicine, and a medical degree is no longer a prerequisite for entry into specialist training.[14] Specialist training is normally 5 years, although this may be reduced to a minimum of 3 years in recognition of previous training, such as a medical degree.[14] In the UK, oral medicine is one of the smallest dental specialties.[15] According to the GDC, as of December 2014 there were 69 clinicians registered as specialists in oral medicine.[16] As of 2012, there were 16 oral medicine units across the UK, mostly based in dental teaching hospitals,[14] and around 40 practising consultants.[15] The British & Irish Society for Oral Medicine has suggested that there are not enough oral medicine specialists, and that there should be one consultant per million population.[15] Competition for the few training posts is keen, although new posts are being created and the number of trainees increased.[15]

United States

The American Dental Association (CODA) accredited programs are a minimum of two years in length. Oral medicine, is an American Dental Association recognized speciality, and many oral medicine specialists fulfil a very important role by teaching at dental schools and graduate programs to ensure dentists and other dental specialists receive excellent training in medical topics pertinent to the dental practice. The ADA has recently started a dental practice parameters for world-class quality services.

References

- "Odd Tongues: The Prevalence of Lingual Disease". The Maxillofacial Center for Diagnostics & Research. Archived from the original on 11 October 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- John, Pramod (2014). Textbook of oral medicine (3rd ed.). JP Medical Ltd. ISBN 9789350908501.

- "Bond's Book of Oral Disease". The Maxillofacial Center for Education & Research. Archived from the original on 2015-02-06.

- "Career Paths of Oral Medicine Doctors". American Academy of Oral Medicine. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- Shephard, Martina K.; MacGregor, E. Anne; Zakrzewska, Joanna M. (December 2013). "Orofacial Pain: A Guide for the Headache Physician". Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 54 (1): 22–39. doi:10.1111/head.12272. PMID 24261452.

- "Oral Pyogenic Granuloma: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology". 2019-02-01. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Dental cysts | Cambridge University Hospitals". www.cuh.nhs.uk. Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- Felix, David H; Luker, Jane; Scully, Crispian (2013-10-02). "Oral medicine: 11. lumps and swellings: mouth". Dental Update. 40 (8): 683–687. doi:10.12968/denu.2013.40.8.683. ISSN 0305-5000.

- Crispian., Scully (2008). Oral and maxillofacial medicine : the basis of diagnosis and treatment (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 9780443068188. OCLC 123962943.

- "Proposed prescribed qualification for the Dental Specialty: Oral Medicine Scope of Practice" (PDF). Dental Council, New Zealand. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- "Specialist lists". General Dental Council.

- "Look for a specialist". General Dental Council. Archived from the original on 2014-12-08. Retrieved 2014-12-07.

- "What is Oral Medicine?". British Society for Oral Medicine. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- "Specialty Training Curriculum for Oral Medicine" (PDF). General Dental Council. July 2010.

- Clare Marney; Jim Killgore (7 December 2012). "Where dentistry meets medicine" (PDF). Medical and Dental Defence Union of Scotland. p. Soundbite; Issue 06 pp 8–9.

- "Facts and figures from the GDC register December 2014" (PDF). General Dental Council.

External links

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Oral medicine |