Orok language

Orok (also Ulta ульта, or Uilta, Ujlta уйльта[3]) is a language of the Manchu-Tungus family spoken in the Poronaysky and Nogliksky Administrative Divisions of Sakhalin Oblast, in the Russian Federation, by the small nomadic group known as the Orok or Ulta.The designation of Uilta may be related to the word ulaa which translates to ‘domestic reindeer’. The northern Uilta who live along the river of Tym’ and around the village of Val have reindeer herding as one of their traditional occupations.The group of southern Uilta live along the Polonay down the near city of Polonask. The two dialects come from northern and eastern groups, however having very few differences. The geographical spread of the language consists of the Sakhalin Province, Russian confederation, the Nogilkskiy District, and Poronayask. Some of the language contacts are Evek, Nivkhi, Ainu, Russian languages, and Japanese.

| Orok | |

|---|---|

| Uilta | |

| Native to | Russia, Japan |

| Region | Sakhalin Oblast (Russian Far East), Hokkaido |

| Ethnicity | 300 Orok (2010 census)[1] |

Native speakers | 26–47 (2010 census)[1] |

Tungusic

| |

| Cyrillic | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | oaa |

| Glottolog | orok1265 |

| ELP | Orok[2] |

Classification

Orok is closely related to Nanai, and is classified within the southern branch of the Manchu-Tungus languages. Classifications which recognize an intermediate group between the northern and southern branch of Manchu-Tungus classify Orok (and Nanai) as Central Tungusic. Within Central Tungusic, Glottolog groups Orok with Ulch as "Ulchaic", and Ulchaic with Nanai as "Central-Western Tungusic" (also known as the "Nanai group"), while Oroch, Kilen and Udihe are grouped as "Central-Eastern Tungusic".[4]

Distribution

Although there has been an increase in the total population of the Uilta there has been a decrease in persons who speak Ulta as their mother tongue. The total population of Ulta was at 200 in the 1989 census of which 44.7, then increased to approximately 300-400 persons. However, the number of native speakers decreased to 25-16 persons. According to the results of the Russian population census of 2002, Ulta (Orok) (all who identified themselves as “Oroch with Ulta language”, “Orochon with Ulta language”, “Uilta”, “Ulta”, “Ulch with Ulta language” were attributed to Ulta) count 346 people, 201 of them – urban and 145 – village dwellers.The percentage of 18.5%, which is 64 persons pointed that they have a command of their (“Ulta”)language, which, mostly, should be considered as a result of increased national consciousness in the post-Soviet period than a reflection of the real situation. In fact, the number of those people with a different degree of command of the Ulta language is less than 10 and the native language of the population is overwhelmingly Russian. Therefore because of the lack of a practical writing system and sufficient official support the Orok language has become an endangered language.

The language is critically endangered or moribund. According to the 2002 Russian census there were 346 Oroks living in the north-eastern part of Sakhalin, of whom 64 were competent in Orok. By the 2010 census, that number had dropped to 47. Oroks also live on the island of Hokkaido in Japan, but the number of speakers is uncertain, and certainly small.[5] Yamada (2010) reports 10 active speakers, 16 conditionally bilingual speakers, and 24 passive speakers who can understand with the help of Russian. The article states that "It is highly probable that the number has since decreased further."[6]

Orok is divided into two dialects, listed as Poronaisk (southern) and Val-Nogliki (northern).[4] The few Orok speakers in Hokkaido speak the southern dialect. "The distribution of Uilta is closely connected with their half-nomadic lifestyle, which involves reindeer herding as a subsistence economy."[6] The Southern Orok people stay in the coastal Okhotsk area in the Spring and Summer, and move to the North Sakhalin plains and East Sakhalin mountains during the Fall and Winter. The Northern Orok people live near the Terpenija Bay and the Poronai River during spring and summer, and migrate to the East Sakhalin mountains for autumn and winter.

Contributions

Takeshiro Matsuura(1818-1888), a prominent Japanse explorer of Hokkaido, southern Skhalin, and the Kurile Islands , was the first to take a noteworthy record of the language. Matsuura wrote down about 350 Uilta words in Japanese also including about some 200 words with grammatical remarks and short texts. The oldest set of known record of the Uilta language is a 369-entry collection of words and short sample sentences, under the title “Worokkongo”, dating from the mid-nineteen century. Japanese researcher Akira Nakanome under the Japanese occupation of South Sakhalin investigated the Uilta language and therefore published a small grammar with a glossary of 1000 words. Other investigators who published some work on the Uilta were Hisharu Magata, Hideya Kawamura, T.I Petrova, A.I Novikova, L.I Sem and contemporary specialist L.V. Ozolinga. Magata published a substantial volume of dictionaries under “A Dictionary of the Uilta Language/ Uirutago Jiten”(1981). Others adding to the creation of an Uilta language were Ozolinga who published two substantial dictionaries one in 2001 with 1200 words included and in 2003 with 5000 words of Uilta-Russian parts and with 400 Russian-Uilta entries.

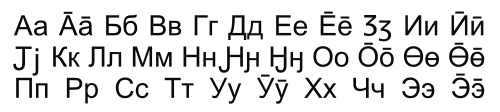

Alphabet

An alphabetic script, based on Cyrillic, was introduced in 2007. A primer has been published, and the language is taught in one school on the island of Sakhalin.[7]

The letter "en with left hook" has been included in Unicode since version 7.0.

In 2008, the first Uilta primer was published to set a writing system and to educated local speakers of Uilta.[8]

Morphology

Orok language is formed by elements called actor nouns. These actor nouns are formed when a present participle is combined with the noun - ɲɲee. In Orok, for example, the element - ɲɲee (< *ɲia), has become a general suffix for ´humans´, as in ǝǝktǝ-ɲɲee ‛woman’, geeda-ɲɲee ‛one person’ and xasu-ɲɲee ‛how many people?’. Much of what constitutes Orok and its forms can be traced back to the Ulcha language. It is from there that the more peculiar features of Orok have its origins.

Orok has participial markers for three tenses: past, -xa(n-), present, +ri, and future, -li, When the participle of an uncompleted action, +ri, is combined with the suffix, -la, it creates the future tense marker +rila-. It also has the voluntative marker (‘let us…!’) +risu, in which the element -su diachronically represents the 2nd person plural ending. Further forms were developed that were based on the +ri: the subjunctive in +rila-xa(n-) (fut-ptcp.pst-), the 1st person singular optative in +ri-tta, the 3rd person imperative in +ri-llo (+ri-lo), and the probabilitative in +ri-li- (ptcp.prs-fut).

In possessive forms and if the possessor is human. The suffix - ɲu, is always added following the noun-stem. The suffix -ɲu indicates that the referent is in indirect or an alienable possession to the possessor. To indicate a direct and inalienable possession between the referent and the possessor, the suffix - ɲu, is omitted. For example, ulisep -ɲu- bi ʻmy meatʼ vs. ulise-bi ʻmy fleshʼ, böyö -ɲu- bi ʻmy bearʼ vs. ɲinda-bi ʻmy dogʼ, sura - ɲu - bi ʻmy fleaʼ vs. cikte-bi ʻmy louseʼ, kupe - ɲu - bi ʻmy threadʼ vs. kitaam-bi ʻmy needle.

Pronouns are divided into four groups: personal, reflexive, demonstrative, and interrogative. Orok personal pronouns have three persons (first, second and third) and two numbers (singular and plural). SG - PL 1st bii – buu 2nd sii – suu 3rd nooni – nooci. [9] [10]

Phonology

Syllable and Mora

Syllable structure can be represented as Consonant, Vowel, Vowel, Consonant, or CVVC. Any consonant may be the syllable at the beginning of a word (syllable- initial) or the very last syllable (syllable- final). Furthermore, syllables in this case can be divided into moras, which are basically rhythmic units, it determines stress and timing of the word and can be ranked as primary or secondary. [8] Any word typically contains a minimum of two moras, and monosyllabic words will always have VV. [8] Therefore, in any case there are no words with the structure of C, V, C.

Sentence Structure

The order in the noun phrase has the order determiner, adjective, and noun. As you can see in these examples.

Tari goropci nari

Det Adj N

That old man'.

eri goropci nari

Det Adj N

‘This old man.’

Arisal goropci nari-l

Det Adj N

‘Those old men’.

If you have subject and verb then you have the order subject and verb. As you can see in these examples.

Bii xalacci-wi

S V

‘I will wait’.

ii bii ŋennɛɛ-wi

S V

‘Yes, I will go’.

A sentence with a subject, object, and verb has the order subject, object, and verb. As you can see in this example.

sii gumasikkas nu-la

S O V

‘You have money’.

A sentence with determiner, subject, noun, adjective, and verb has the order of a noun phrase. As you can see in this example.

tari nari caa ninda-ji kusalji tuksɛɛ -ni

Det, S, N Adj V

‘That man runs faster than that dog’.

A sentence where the complement comes after its complement is a postposition. As you can see in this example.

sundattaa dug-ji bii-ni

N, N Post

‘The fish (sundattaa) is at home (dug-ji)’.

See also

References

- Orok at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- Endangered Languages Project data for Orok.

- Uilta may come from the word ulaa which means 'domestic reindeer'. Tsumagari, Toshiro, 2009: "Grammatical Outline of Uilta (Revised)". Hokkaido University

- Hammarström, Harald; Forke, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2020). "Orok". Glottolog 4.3.

- Novikova, 1997

- Yamada, Yoshiko, 2010: "A Preliminary Study of Language Contacts around Uilta in Sakhalin". Hokkaido University.

- Уилтадаирису (in Russian; retrieved 2011-08-17) ("Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link))

- Tsumagari, Toshiro, 2009: "Grammatical Outline of Uilta (Revised)". Hokkaido University

- https://eprints.lib.hokudai.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2115/37062/1/TSUMAGARI.pdf

- @inproceedings{Pevnov2016OnTS, title={On the Specific Features of Orok as Compared with the Other Tungusic Languages}, author={A. Pevnov}, year={2016} }

- Chai, Tianfeng (4 October 2018). "Revised Manuscript (pdf file)". dx.doi.org. doi:10.5194/gmd-2018-159-ac4. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

Further reading

- Majewicz, A. F. (1989). The Oroks: past and present (pp. 124–146). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Pilsudski, B. (1987). Materials for the study of the Orok [Uilta] language and folklore. In, Working papers / Institute of Linguistics Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu.

- Matsumura, K. (2002). Indigenous Minority Languages of Russia: A Bibliographical Guide.

- Kazama, Shinjiro. (2003). Basic vocabulary (A) of Tungusic languages. Endangered Languages of the Pacific Rim Publications Series, A2-037.

- Yamada, Yoshiko. (2010). A Preliminary Study of Language Contacts around Uilta in Sakhalin. Journal of the Center for Northern Humanities 3. 59–75.

- Tsumagari, T. (2009). Grammatical Outline of Uilta (Revised). Journal of the Graduate School of Letters, 41–21.

- Ikegami, J. (1994). Differences between the southern and northern dialects of Uilta. Bulletin of the Hokkaido Museum of Northern Peoples, 39–38.

- Knüppel, M. (2004). Uilta Oral Literature. A Collection of Texts Translated and Annotated. Revised and Enlarged Edition . (English). Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 129(2), 317.

- Smolyak, A. B., & Anderson, G. S. (1996). Orok. Macmillan Reference USA.

- Missonova, L. (2010). The emergence of Uil'ta writing in the 21st century (problems of the ethno-social life of the languages of small peoples). Etnograficheskoe Obozrenie, 1100–115.

- Larisa, Ozolinya. (2013). A Grammar of Orok (Uilta). Novosibirsk Pablishing House Geo.

- Janhunen, J. (2014). On the ethnonyms Orok and Uryangkhai. Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia, (19), 71.

- Pevnov, A. M. (2009, March). On Some Features of Nivkh and Uilta (in Connection with Prospects of Russian-Japanese Collaboration). In サハリンの言語世界: 北大文学研究科公開シンポジウム報告書= Linguistic World of Sakhalin: Proceedings of the Symposium, 6 September 2008 (pp. 113–125). 北海道大学大学院文学研究科= Graduate School of Letters, Hokkaido University.

- Ikegami, J. (1997). Uirutago jiten [A dictionary of the Uilta language spoken on Sakhalin].

- K.A. Novikova, L.I. Sem. Oroksky yazyk // Yazyki mira: Tunguso-man'chzhurskie yazyki. Moscow, 1997. (Russian)

| Orok language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |