Pale Rider

Pale Rider is a 1985 American Western film produced and directed by Clint Eastwood, who also stars in the lead role. The title is a reference to the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, as the rider of a pale horse is Death. The film, which took in nearly $41 million at the box office, became the highest grossing Western of the 1980s.[3]

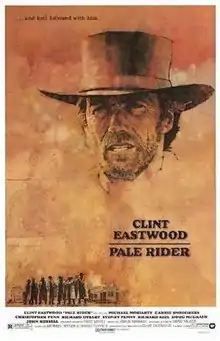

| Pale Rider | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by C. Michael Dudash | |

| Directed by | Clint Eastwood |

| Produced by | Clint Eastwood |

| Written by | Michael Butler Dennis Shryack |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Lennie Niehaus |

| Cinematography | Bruce Surtees |

| Edited by | Joel Cox |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6.9 million[1] |

| Box office | $41.4 million[2] |

Plot

Outside the snowy mountain town of Lahood, California, thugs working for big-time miner Coy LaHood destroy the camp of a group of prospectors and their families. They shoot a dog belonging to 14-year-old Megan Wheeler, who prays for a miracle as she buries its body in the woods. Thunder rolls and a stranger rides down the slopes.

Megan's mother, Sarah, is being courted by Hull Barret. When Hull heads to town to pick up supplies, four of the thugs begin to beat him with axe handles, but he is rescued by the stranger. Hull then invites his rescuer to dinner and, while the stranger is washing, notices what look like six bullet wounds in his back. When the stranger appears at the dinner table, he is wearing a clerical collar and is thereafter called "Preacher".

Coy LaHood's son Josh attempts to scare off the Preacher with a show of strength from his giant work hand, Club, who breaks a large rock in half with a single hammer blow. Club attempts to attack the Preacher, who hits Club in the face with his hammer and delivers a blow to the groin, then gently helps him onto his horse. Afterwards the miners work together to smash the rest of the boulder.

Meanwhile, Coy LaHood returns from Sacramento and is furious to learn about the Preacher’s arrival, saying that this would strengthen the resolve of the prospectors. Failing to bribe the Preacher into settling in the town, LaHood is persuaded to offer the miners $1000 per claim provided they evacuate within 24 hours. LaHood threatens to hire a corrupt marshal named Stockburn to clear them out if they refuse. The miners initially consider the offer but, when Hull reminds them of their purpose and sacrifices, they decide to stay and fight.

Next morning, the Preacher leaves without notice and retrieves his revolver from a bank box. Meanwhile, the miners find that LaHood's men have dammed the creek running through their camp. They agree to stay and continue panning the drying creek bed.

Megan rides into the LaHood strip mining camp where Josh attempts to rape her while his cohorts encourage him. The Preacher arrives on horseback and rescues Megan, shooting Josh in the hand in the process.

Now Stockburn and his six deputies arrive at the town. LaHood describes the Preacher to Stockburn, who appears startled and says that it sounds like someone he once knew but who is now dead.

Spider Conway, a miner at the camp, recovers a large gold nugget and rides into town, where he yells drunken abuse at LaHood from the street. After gunning him down, Stockburn tells Spider's sons to tell the Preacher to meet him in town the next morning. Sarah goes to the barn where the Preacher is sleeping and it is implied they have sex.

The following day, the Preacher and Hull blow up LaHood's site with dynamite. To stop Hull from following him, the Preacher scares off Hull's horse and rides into town alone. In the gunfight that follows, he kills all but the two of LaHood's men who run away, and then, one by one, all six of Stockburn's deputies as they spread through the town searching for him. When he goes face-to-face with Stockburn, the latter recognizes him in disbelief and goes for his gun. The Preacher draws first, sending six bullets through his torso before shooting him in the head. LaHood, watching from his office, aims a rifle at the Preacher but is shot by Hull and crashes through the window.

The Preacher nods at Hull and remarks, "Long walk", before leading his horse from the stable and galloping toward the snow-capped mountains. Megan drives into town too late and shouts her love and thanks to the Preacher. Her words echo through the canyon as he rides off.

Cast

- Clint Eastwood as the Preacher

- Michael Moriarty as Hull Barret

- Carrie Snodgress as Sarah Wheeler

- Richard Dysart as Coy LaHood

- Chris Penn as Josh LaHood

- Sydney Penny as Megan Wheeler

- John Russell as Marshal Stockburn

- Richard Kiel as Club

- Doug McGrath as Spider Conway

- Chuck Lafont as Eddie Conway

- Jeffrey Weissman as Teddy Conway

- Charles Hallahan as McGill

- Marvin J. McIntyre as Jagou

- Fran Ryan as Ma Blankenship

- Richard Hamilton as Pa Blankenship

- Terrence Evans as Jake Henderson

Production

Pale Rider was primarily filmed in the Boulder Mountains and the Sawtooth National Recreation Area in central Idaho, just north of Sun Valley in late 1984.[4] The opening credits scene featured the jagged Sawtooth Mountains south of Stanley. Train-station scenes were filmed in Tuolumne County, California, near Jamestown. Scenes of a more established Gold Rush town (in which Eastwood's character picks up his pistol at a Wells Fargo office) were filmed in the real Gold Rush town of Columbia, also in Tuolumne County.[5]

Crew

- Clint Eastwood Producer/Director/Star

- Lennie Niehaus Composer

- Bruce Surtees Director of Photography

- Joel Cox Film Editing

- Edward Carfagno Production Design

- Chuck Gaspar Special Effects

- Buddy Van Horn Stunt Coordinator

- Jack N. Green Camera Operator

- Marcia Reed Still Photographer

- Deborah Hopper Costume Designer/Wardrobe: Women

Religious themes

In an audio interview, Clint Eastwood said that his character Preacher "is an out-and-out ghost."[6] However, whereas Eastwood's 1973 western, High Plains Drifter resolves its storyline by means of a series of unfolding flashback narratives (although ambiguity still remains), Pale Rider does not include any such obvious clues to the nature and past of the Preacher other than six bullet wound scars on his back. Viewers are left to draw their own conclusions regarding the overall story line and its meaning.

The movie's title is taken from the Book of Revelation, chapter 6, verse 8: "And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him." The reading of the biblical passage describing this character is neatly choreographed to correspond with the sudden appearance of the Preacher, who arrived as a result of a prayer from Megan, in which she quoted Psalm 23. Preacher's comment after beating one of the villains is, "Well, the Lord certainly does work in mysterious ways." After the temptation to shift his ministry to the town, Preacher says, "You can't serve God and Mammon, Mammon being money."[7] According to Robert Jewett, the film's dialogue parallels Paul the Apostle's teaching on divine retribution (Romans 12:19–21).[7]

Reception

Box office

Pale Rider was released in the United States in June 1985, and became one of the highest-grossing Westerns of the 1980s.[8] It was the first mainstream Hollywood Western to be produced after the massive financial failure of Heaven's Gate.

The movie was a success at the North American box office, grossing $41,410,568[9] against a $6,900,000 budget.[10][11]

Critical response

On Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 93% based on reviews from 27 critics.[12] On Metacritic the film has a score of 61% based on reviews from 13 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[13]

Roger Ebert praised the film, giving it four out of four stars. Further, he stated, "Pale Rider is, overall, a considerable achievement, a classic Western of style and excitement."[14] Vincent Canby of The New York Times praised Clint Eastwood saying "This veteran movie icon handles both jobs with such intelligence and facility I'm just now beginning to realize that, though Mr. Eastwood may have been improving over the years, it's also taken all these years for most of us to recognize his very consistent grace and wit as a film maker."[15]

Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune noted that Westerns were out of fashion "but fresh and challenging westerns with Clint Eastwood always will be in vogue"[16] whereas Rita Kemply of The Washington Post criticized the lack of originality "The trail is all too familiar and pretty soon we recollect why westerns lost their appeal.".[17]

The film was entered into the 1985 Cannes Film Festival.[8][18]

Pale Rider was included in the Western nominations for the American Film Institute's 10 Top 10 lists.[19]

Film score

One of the film's scores (used in a trailer) was composed by British composer Alan Hawkshaw, who wrote the original theme for BBC children's drama series Grange Hill, as well as the signature tunes for Channel 4’s Countdown and Channel 4 News.

In an odd case of doubling up in Hawkshaw's career, according to an interview in a BBC Radio 4 documentary, “The Lost Art of the Theme Tune”, Channel 4 News did not secure permanent exclusivity rights to Hawkshaw's theme, known as "Best Endeavours", resulting in it also being used for the trailer for Pale Rider.[20]

References

- Box Office Information for Pale Rider. Archived 2014-12-15 at the Wayback Machine The Wrap. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- Box Office Information for Pale Rider. Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- Barnes, Mike (September 15, 2016). "Dennis Shryack, Screenwriter on Clint Eastwood's 'The Gauntlet' and 'Pale Rider,' Dies at 80". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- "Eastwood film gives boost". Spokane Chronicle. Washington. Associated Press. November 30, 1984. p. 12.

- Hughes 2009, p. 36.

- "Clint Eastwood.net Filmography / Pale Rider". Retrieved February 12, 2008.

- Clive Marsh, Gaye Ortiz, Explorations in theology and film: movies and meaning, Blackwell Publishers 1997 (reprint 2001), p. 68

- Hughes 2009, p. 38.

- "Pale Rider (1985)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb.com, Inc. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- "Pale Rider movie info". Mooviees!. 2002. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- "Disasters Outnumber Movie Hits". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. September 4, 1985. Archived from the original on October 14, 2018. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- "Pale Rider (1985)". Rotten Tomatoes.

- "Pale Rider". Metacritic.

- Ebert, Roger (June 28, 1985). "Pale Rider". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- Canby, Vincent (June 28, 1985). "Film: Clint Eastwood in 'Pale Rider'". The New York Times.

- Gene Siskel. "`PALE RIDER` JUST ANOTHER GALLOP FOR THE HIGH PLAINS DRIFTER". Chicago Tribune.

- Kempley, Rita (June 28, 1985). "'Pale Rider,' Stale Trail". Washington Post.

- "Festival de Cannes: Pale Rider". festival-cannes.com. 1985. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). AFI's 10 Top 10. American Film Institute. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- "Surprising facts about BBC theme tunes you've heard hundreds of times - BBC Music". www.bbc.co.uk. June 29, 2016. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

Further reading

- Hughes, Howard (2009). Aim for the Heart. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-902-7.

External links

- Pale Rider at IMDb

- Pale Rider at the TCM Movie Database

- Pale Rider at AllMovie