White Hunter Black Heart

White Hunter Black Heart is a 1990 American adventure drama film produced, directed by, and starring Clint Eastwood and based on the 1953 book of the same name by Peter Viertel. Viertel also co-wrote the script with James Bridges and Burt Kennedy. The film is a thinly disguised account of Viertel's experiences while working on the classic 1951 film The African Queen, which was shot on location in Africa at a time when location shoots outside of the United States for American films were very rare. The main character, brash director John Wilson, played by Eastwood, is based on real-life director John Huston. Jeff Fahey plays Pete Verrill, a character based on Viertel. George Dzundza's character is based on African Queen producer Sam Spiegel. Marisa Berenson's character Kay Gibson and Richard Vanstone's character Phil Duncan are based on Katharine Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart, respectively. This was the last film that James Bridges worked on writing down a screenplay, before dying in 1993.

| White Hunter Black Heart | |

|---|---|

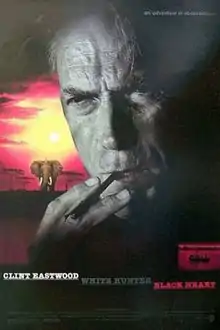

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Clint Eastwood |

| Produced by | Clint Eastwood |

| Screenplay by | Peter Viertel James Bridges Burt Kennedy |

| Based on | White Hunter, Black Heart by Peter Viertel |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Lennie Niehaus |

| Cinematography | Jack N. Green |

| Edited by | Joel Cox |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 110 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $24 million[1] |

| Box office | $2 million[1] |

Plot

In the early 1950s, world-renowned film-maker John Wilson travels to Africa for his next film, bringing with him a young writer chum named Pete Verrill. Part of his travel plans include hunting elephants and other game, which he prioritizes ahead of making the film. This leads to a conflict between the men on several levels, most notably over the idea of killing for sport such a grand animal. Wilson concedes that it is so wrong that it is not just a crime against nature, but a "sin" and that is the reason he wants to do it. He cannot overcome his desire to bring down a giant bull, a "tusker" with massive ivory tusks. Wilson's final realization that his is a petty, ignoble pursuit comes at a late point and with a tragic price, as the local animal tracker Kivu is killed protecting him from an elephant Wilson decides not to shoot.

Cast

- Clint Eastwood as John Wilson

- Jeff Fahey as Pete Verrill

- Alun Armstrong as Ralph Lockhart

- George Dzundza as Paul Landers

- Charlotte Cornwell as Miss Wilding, Wilson's secretary

- Norman Lumsden as Butler George

- Marisa Berenson as Kay Gibson

- Richard Vanstone as Phil Duncan

- Catherine Neilson as Irene Saunders

- Edward Tudor-Pole as Reissar, British partner

- Roddy Maude-Roxby as Thompson, British partner

- Richard Warwick as Basil Fields, British partner

- Boy Mathias Chuma as Kivu

- Timothy Spall as Hodkins, bush pilot

Production

At times, Eastwood, as the John Huston-like character of John Wilson, can be heard drawing out his vowels, speaking in Huston's distinctive style.

The film was shot on location in Kariba, Zimbabwe, and surrounds including at Lake Kariba, Victoria Falls, and Hwange,[2] over two months in the summer of 1989.[3] Some interiors were shot in and around Pinewood Studios in England. The boat used in the film was constructed in England of glass fibre and shipped to Africa for filming.[2] It was electrically powered, and was fitted with motors and engines by special-effects expert John Evans to make the boat appear to be steam-powered.[2] The elephant gun used in the film was a £65,000 double-barrelled rifle of the type preferred by most professional hunters and their clients in this era. It was made by Holland & Holland, the gunmakers who also made the gun used by Huston when he was in Africa for The African Queen in 1951. The White Hunter Black Heart filmmakers took great care with the gun and sold it back to Holland & Holland after filming "unharmed, unscratched, unused."[2]

Actor Clive Mantle, who plays the racist hotel manager Harry, has the distinction of being the only person to successfully beat up Clint Eastwood in a film (not counting Every Which Way But Loose when he intentionally loses). Mantle was roughly half Eastwood's age and reportedly had trouble keeping up with him during filming of the fight scene. Although Eastwood had suffered beatings in other films, most notably Dirty Harry, its sequel Sudden Impact, and later Unforgiven, they usually involved him being outnumbered or outmatched; this was the only time he was defeated in a fair fight.

Critical reception

The film was entered into the 1990 Cannes Film Festival.[4] The film received positive reviews with review tallying website Rotten Tomatoes reporting that 30 out of the 35 reviews they tallied were positive giving a 86% rating. The consensus reads: "White Hunter Black Heart is powerful, intelligent, and subtly moving, a fascinating meditation on masculinity and the insecurities of artists."[5]

The film has grown significantly in critical stature, especially in light of the films Eastwood made immediately afterwards. Many of these, like White Hunter, Black Heart, turned out to be self-reflexive and self-conscious works criticizing and deconstructing Eastwood's own iconography. Jim Hoberman of The Village Voice hailed it as "Eastwood’s best work before Unforgiven...[an] underrated hall-of-mirrors movie about movie-inspired megalomania."[6] Dave Kehr and Jonathan Rosenbaum consider it a masterpiece, with the latter pointing out the Brechtian nature of Eastwood's performance, as he never disappears into the role he is playing; instead, Eastwood is always recognizably his unique star persona while showing us what he imagines Huston (i.e. Wilson) to have been. The result is "a running commentary on his two subjects, Huston and himself—the ruminations and questions of a free man."[7]

Box office

White Hunter Black Heart's gross theatrical earnings reached just over $2 million, well below the film's $24 million budget.[1]

References

- Hughes, Howard, Aim for the Heart: The Films of Clint Eastwood, p.147, I.B. Tauris, London, 2009, ISBN 978-1-84511-902-7.

- Production designer John Graysmark interview, Cue International May 1990.

- Hughes, Howard, Aim for the Heart: The Films of Clint Eastwood, p.144, I.B. Tauris, London, 2009, ISBN 978-1-84511-902-7.

- "Festival de Cannes: White Hunter Black Heart". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- "White Hunter Black Heart (1990)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- Hoberman, Jim (July 13, 2010). "Voice Choices: White Hunter, Black Heart". The Village Voice. Retrieved 2015-01-04.

- Rosenbaum, Jonathan (December 1, 2009). "A Free Man". Retrieved 2015-01-04.