Panama–California Exposition

The Panama–California Exposition was an exposition held in San Diego, California, between January 1, 1915, and January 1, 1917. The exposition celebrated the opening of the Panama Canal, and was meant to tout San Diego as the first U.S. port of call for ships traveling north after passing westward through the canal. The fair was held in San Diego's large urban Balboa Park.

| 1915–1916 San Diego | |

|---|---|

Official guide book | |

| Overview | |

| BIE-class | Unrecognized exposition |

| Name | Panama–California Exposition |

| Area | 640 acres (260 hectares) |

| Visitors | 3,747,916 |

| Organized by | Panama–California Exposition Company |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| City | San Diego |

| Venue | Balboa Park |

| Coordinates | 32°43′53″N 117°09′01″W |

| Timeline | |

| Opening | January 1, 1915 |

| Closure | January 1, 1917 |

| Specialized expositions | |

| Simultaneous | |

| Other | Panama–Pacific International Exposition (San Francisco) |

Proposal and formation

Beginning on July 9, 1909, San Diego's Chamber of Commerce president and local businessman Gilbert Aubrey Davidson proposed an exposition to commemorate the completion of the Panama Canal.[1] San Diego by 1910 had a population of 37,578,[2] and would be the least populated city to ever host an international exposition.[1] In contrast, San Francisco had a population nearly 10 times larger[2] and would ultimately be supported by politicians in California and Washington, D.C. for the official Panama Canal exposition, the Panama–Pacific International Exposition. Although representatives from San Francisco urged San Diego to end its planning, San Diego pressed forward for a simultaneous exposition.[3] Several San Franciscans persuaded both members of Congress and President William Howard Taft to deny support for San Diego's exposition in exchange for pledged political support for Taft's campaign against Republicans.[4] With no federal and little state government funding, San Diego's exposition would be on a smaller scale with fewer states and countries participating.[5][6]

The Panama–California Exposition Company was formed in September 1909 and its board of directors was soon led by president Ulysses S. Grant, Jr. and vice president John D. Spreckels.[1] After Grant resigned in November 1911, real estate developer "Colonel" D. C. Collier, was made president of the exposition.[7] He was responsible for selecting both the location in the city park and the Pueblo Revival and Mission Revival architectural styles.[8] Collier was tasked with steering the exposition in 'the proper direction,' ensuring that every decision made reflected his vision of what the exposition could accomplish. Collier once stated "The purpose of the Panama–California Exposition is to illustrate the progress and possibility of the human race, not for the exposition only, but for a permanent contribution to the world's progress."[9] The exposition's leadership changed again in early March 1914, when Collier encountered personal financial issues and resigned. He was replaced by Davidson who was also joined by several new vice presidents.[10]

By March 1910, $1 million ($27,439,286 today) was raised for the expo by the Panama–California Exposition Company through selling subscriptions.[11] Further, by August a voter-approved bond provided an additional $1 million solely for improving permanent fixtures in the park. Funding for the California State Building was provided through appropriation bills totaling $450,000 ($12,347,679 today) signed by Governor Hiram Johnson in both 1911 and 1913.[12]

Design

Fair officials first sought architect John Galen Howard as their supervisory architect. With Howard unavailable, on January 27, 1911, they chose New York architect Bertram Goodhue in that role, also appointing Irving Gill to assist Goodhue.[13] By September 1911 Gill had resigned and was replaced by Carleton Winslow of Goodhue's office, just as the original landscape architects, the Olmsted Brothers had left and were replaced in their role by fair official Frank P. Allen, Jr.[8]

Exposition site

The exposition's location was selected to be inside the 1,400 acres (570 ha) of Balboa Park. For the first few decades of its existence, "City Park" remained mostly open space. The land, lacking trees and covered in native wildflowers, was home to bobcats, rattlesnakes, coyotes, and other wildlife.[14] Numerous proposals, some altruistic, some profit-driven, were brought forward for the development and use of the land during this time. Several buildings including a high school, nursery, and gunpowder magazine were eventually built in the park, prior to the initial 1909 plan proposed by Davidson. During construction in 1910, a contest was held that renamed the park after Vasco Núñez de Balboa, the first European to cross Central America and see the Pacific Ocean.[15]

Two north-south canyons — Cabrillo Canyon and Florida Canyon — traverse the park and separate it into three mesas.[16] Cabrillo Canyon (formerly known as Pound Canyon) forms a deep separation between the exposition site and the park entrance from downtown San Diego. The park is essentially rectangular, now bounded by Sixth Avenue to the west, Upas Street to the north, 28th Street to the east, and Russ Boulevard to the south.

Spanish Colonial Revival architecture

Goodhue and Winslow advocated a design that turned away from the more modest, indigenous, horizontally oriented Pueblo Revival and Mission Revival, towards a more ornate and urban Spanish Baroque. Contrasting with bare walls, rich Mexican and Spanish Churrigueresque decoration would be used, with influences from the Islamic and Persian styles in Moorish Revival architecture.

For American world's fairs, this was a novelty. The design was intentionally in contrast to most previous Eastern U.S. and European expositions, which had been done in neoclassical and Beaux-Arts styles, with large formal buildings around large symmetric spaces. Even San Francisco's simultaneous Panama–Pacific International Exposition was largely, though not exclusively, in Beaux-Arts style.[17]

Goodhue had already experimented with Spanish Baroque in Havana, at the 1905 La Santisima Trinidad pro-cathedral, and the Hotel Colon in Panama. Some of his specific stylistic sources for San Diego are the Giralda Tower at the Seville Cathedral, the Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral, and the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption, Oaxaca.[18]

Goodhue personally designed the largest and most ornate building on the site, the California Building, with its historical iconography; he sketched two other buildings, provided Winslow and Allen with his photographs and drawings from examples in Spain and Mexico, and reviewed their developed designs.[8] The original ensemble of buildings featured various stylistic and period references. Taken together, they constituted something like a recapitulated history of Spanish colonial in North America, from Renaissance Europe sources, to Spanish colonial, to Mexican Baroque, to the vernacular styles adopted by the Franciscan missions up the California coast.[18] The Botanical Building was designed by Winslow with help from Allen and Thomas B. Hunter in the style of a Spanish Renaissance greenhouse.[19]

This mix of influences at San Diego proved popular enough to earn its own name: Spanish Colonial Revival. The Exposition brought Spanish Colonial Revival into becoming California's "indigenous historical vernacular style", very popular in poured concrete through the 1920s, still used and reinterpreted in the present day. To some extent it was even adopted as a southwestern regional style, as seen at the Pima County Courthouse in Tucson, Arizona, with a few minor examples in Phoenix.[20] Prior to the exposition, San Diego had predominately featured Victorian architecture with some elements of classical styles.[21] The popularity of the expo led to more emphasis on mission architecture within the city.

Goodhue moved on to other national projects, while Winslow stayed on in southern California, continued to produce his own variations of the style, at the Bishop's School in La Jolla and the 1926 Carthay Circle Theatre in Los Angeles. Winslow was also instrumental in persuading the city of Santa Barbara to adopt Spanish Colonial Revival as the officially mandated civic style after its 1925 earthquake. The major example from the rebuilding is the Santa Barbara County Courthouse.[22]

The temporary installations, decoration, and landscapes of Balboa Park were created with some large spaces and numerous paths, small spaces, and courtyard Spanish gardens. The location was also moved from a small hillock to a larger and more open area, most of which was intended to be reclaimed by the park as gardens.[23]

Construction

The groundbreaking ceremony for the site of the expo was held on July 19, 1911.[24] To make room for the exposition planned layout, several city buildings, machine shops, and a gunpowder magazine were moved offsite.[25] The first building to begin construction was the Administration Building which started in November 1911 and completed in March 1912.[26] Visitors interested in watching the ongoing construction before the exposition's official opening were charged admission of $0.25 ($6 today).[27]

Exposition layout

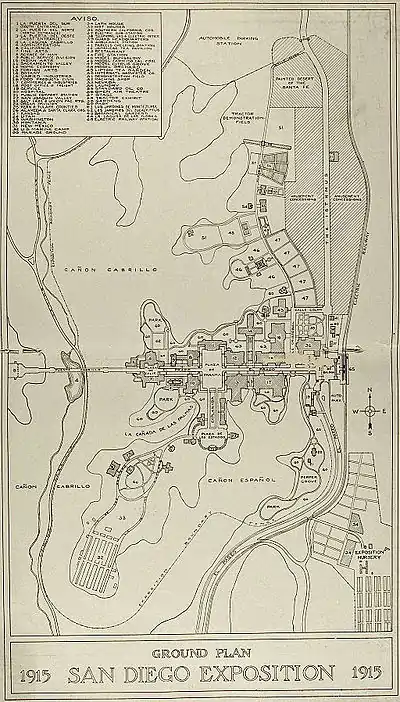

The layout of the 640-acre (260 ha) expo was contained by three entrances on the west, north, and east.[28]

The East Gateway was approached by drive and San Diego Electric Railway trolley cars winding up from the city through the southern portion of the park.

From the west, the Cabrillo Bridge's entrance was marked with blooming giant century plants and led straight to the dramatic West Gate (or City Gate), with the city's coat-of-arms at its crown. The archway was flanked by engaged Doric orders supporting an entablature, with figures symbolizing the Atlantic and Pacific oceans joining waters together, in commemoration of the opening of the Panama Canal. These figures were the work of Furio Piccirilli.

While the west gateway was part of the Fine Arts Building, the east gateway was designed to be the formal entrance for the California State Building. The East or State Gateway carried the California state coat-of-arms over the arch. The spandrels over the arch were filled with glazed colored tile commemorating the 1769 arrival of Spain and the 1846 State Constitutional Convention at Monterey.[23]

Near a large parking lot, the North gate led to the 'Painted Desert' and 2,500-foot (760 m) long Isthmus street. The Santa Fe Railway-sponsored 'Painted Desert' (called "Indian Village" by guests), a 5-acre (2.0 ha), 300-person exhibit populated by seven Native American tribes including the Apache, Navajo, and Tewa.[29][30][31] The 'Painted Desert', which design and construction was supervised by the Southwestern archeologist Jesse L. Nusbaum, had the appearance of a rock structure but was actually wire frames covered in cement.[32]

The Isthmus was surrounded by concessions, amusement rides and games, a replica gem mine, an ostrich farm, and a 250-foot (76 m) replica of the Panama Canal.[30] One of the concessions along the isthmus was a "China Town".[33]

Permanent structures

Intended to be permanent were the Cabrillo Bridge, the domed-and-towered California State Building and the low-lying Fine Arts Building; the latter are now part of the National Register of Historic Places-listed California Quadrangle. The Botanical Building would protect heat-loving plants, while the Spreckels Organ Pavilion would assist open-air concerts in its auditorium. The Botanical Building was completed for $53,400 ($1,363,031 today).[34]

The Cabrillo Bridge was built to span the canyon, and the appearance of its long horizontal stretch ending in a great upright pile of fantasy buildings would be the crux of the whole composition. This design composition and the bridge were designed to remain as a permanent focal point of the city, while many of the exhibit buildings were intended to be temporary.[35]

Upon arrival, the focus of the fair was the Plaza de California (California Quadrangle), an arcaded enclosure often containing Spanish dancers and singers, where both the approach bridge and El Prado terminate. The California State Building and the Fine Arts Building framed the plaza, which was surrounded on three sides by exhibition halls set behind an arcade on the lower story. Those three sides, following the heavy massiveness and crude simplicity of the California mission adobe style, were without ornamentation. This contrasted with the front facade of the California State Building, 'wild' with Churrigueresque complex lines of mouldings and dense ornamentation. Next to the frontispiece, at one corner of the dome, rose the 200 feet (61 m) tower of the California Building, which was echoed in the less prominent turrets of the Southern California counties and the Science and Education buildings. The style of the frontispiece was repeated around the fair.[23]

Temporary buildings

The architecture of the "temporary buildings" was recognized, as Goodhue described, as "being essentially of the fabric of a dream—not to endure but to produce a merely temporary effect. It should provide, after the fashion that stage scenery provides—illusion rather than reality."[23][36]

The "temporary buildings" were formally and informally set on either side of the wide, tree-lined central avenue. El Prado extended along the axis of the bridge and was lined with trees and streetlights, with the front of most buildings lined with covered arcades or portales. The Prado was intended to become the central path of a great and formally designed public garden. The fair's pathways, pools, and watercourses were supposed to remain while the cleared building sites would become garden. Goodhue emphasized that "only by thus razing all of the Temporary Buildings will San Diego enter upon the heritage that is rightfully hers".[23] However, many of the "temporary" buildings were retained and reused for the 1935 fair. Four of them were demolished and rebuilt in their original style toward the end of the 20th century; they are now called the House of Charm, the House of Hospitality, Casa del Prado, and Casa de Balboa, and are included in the National Register of Historic Places-listed El Prado Complex.

Transportation

One of the main considerations for San Diego leaders concerning the Panama–California Exposition was transportation. At the request of John D. Spreckels and his San Diego Electric Railway Company, the park's layout design incorporated an electric railway that ran near the east gate of the park.[37][38] To service the large number of people that were to attend the exposition, streetcars were built that could handle the traffic of the event as well as the growing population of San Diego. The routes ultimately spanned from Ocean Beach, through Downtown, Mission Hills, Coronado, North Park, Golden Hill, and Kensington, even briefly serving as a link to the U.S.–Mexico border. Today, only three of the original twenty-four Class 1 streetcars remain in existence.[39]

At the beginning of the exposition, 200 small wicker motorized chairs, known as electriquettes, were available for rent by visitors.[40] Constructed by the Los Angeles Exposition Motor Chair Company, these slow-speed transports held two to three people and were used for traveling throughout the majority of the exhibition. For the centennial celebration in 2015, plans are being developed to provide replica electriquettes for visitor rentals.[41]

Other features

Additional elements of the exposition included an aviary, rose gardens, and animal pens.[25] Throughout the exposition grounds there were over two million plants of 1,200 different types.[42] Peacocks and pheasants freely wandered through the fairgrounds, and pigeons were frequently fed by guests.[43]

At the opening of the exposition, it did not feature any buildings that were represented by foreign countries.[5] A handful of U.S states held exhibits southwest of the organ pavilion: Kansas, Montana, New Mexico, Washington, and Utah (Nevada's building was located near the open-air theatre).[5][44] In contrast, the San Francisco Panama-Pacific Exposition featured exhibits from 22 countries and 28 U.S. states.[40] Many of the state buildings would eventually be used for the 1916 extension by various countries. The majority were temporary structures that were demolished after the expo.

The United States Marines, Army, and Navy were featured at the expo, with exhibits, onsite tent cities, parades, band concerts, and live mock battles.[45][46]

Opening of the exposition

At midnight (in San Diego) on December 31, 1914, President Woodrow Wilson ceremoniously pushed a telegraph button in Washington, D.C. to open the expo by turning on the power and lights at the park.[47][48] In addition, a lit balloon located 1,500 feet above the park further brightened the exposition.[49] Guns at the nearby Fort Rosecrans and on Navy ships in San Diego Bay also were fired to signal the opening.[48]

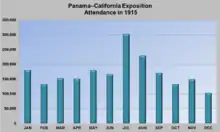

Admission for adults was $0.50 ($13 today) and $0.25 ($6 today) for children.[45] Based on varying sources, the opening day's attendance was between 31,836 and 42,486.[50] By the end of the first month, daily attendance decreased, with an average number of guests at 4,783 a day, which decreased to 4,360 by February.[51] However, in April 1915 it was announced that the expo had already resulted in a $40,000 ($1,010,921 today) profit for the first three months.[52][53] By May, the average daily attendance had increased to 5,800 and in July the total attendance had reached a million visitors.[54]

Notable guests of the event include Vice President Thomas R. Marshall, Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, Franklin D. Roosevelt, then Secretary of the Navy, former presidents William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt, inventor Thomas Edison, and automobile businessman Henry Ford.[36][54][55][56][57] The attempt to "put San Diego on the map" with national attention was successful. Even Pennsylvania's Liberty Bell made a brief three-day appearance in November 1915.[58] At the end of 1915, total visitors reached over two million and the expo had turned a small profit of $56,570 ($1,429,695 today).[58][59]

Extension

Prior to the end of 1915, plans began circulating for extending the exposition for another year. Most of the board of directors, however, were not able to continue into the new year and resigned. Funding for the 1916 addition came from Los Angeles, local businessman, proceeds from the 1915 expo, leftover funding from the Panama–Pacific International Exposition, and chambers of commerce outside of San Diego.[58][60][61] On March 18, 1916 Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels pushed a button in Washington, D.C. that sounded a gong in the Plaza de Panama to commemorate "Exposition Dedication Day".[62] While originally opened as Panama–California Exposition, the fair was rechristened the Panama–California International Exposition.[60] This was actually valid renaming, for while the fair originally had no international exhibitors, by 1916 it had exhibits from Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Russia, and Switzerland.[61][63] Most came from the recently closed Panama–Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco some of whom were unable to return to Europe due to World War I which had been raging since 1914.[64] Additional exhibits included an ice rink, an alligator farm, and performance shows.[65] Some of the original buildings from the prior year were repurposed for new exhibits.[65]

In November 1916, Gilbert Davidson asked the Park Board for an additional three-month extension into 1917,[66] but the expo was concluded on January 1, 1917. Events on the final day included a military parade in the Plaza de Panama, a mock military battle, and an opera ceremony at the organ pavilion. At midnight, the lights were turned off and pyrotechnics above the organ spelled "WORLD PEACE–1917".[59] The total attendance for the second year was just under 1.7 million people.[59] Over the two years a slight profit was earned over the total cost of organizing and hosting the expo.[67][68]

Legacy

—Theodore Roosevelt, speaking at the Spreckels Organ Pavilion on July 27, 1915[54]

Speaking in July 1915, former President Theodore Roosevelt spoke to San Diegans at the Spreckels Organ Pavilion, and requested that San Diego keep the exhibition buildings permanently.[54]

The Exposition's permanent buildings, still standing, include:

- Botanical Building, one of the largest lath-covered structures then in existence, contained a rare collection of tropical and semitropical plants. It is well back from the Prado behind the long pool, La Laguna de Las Flores.

- Cabrillo Bridge (completed April 12, 1914)

- California Bell Tower, completed 1914, 198 feet (60 m) feet tall to the top of the iron weathervane, which is in the form of a Spanish ship; one of the most recognizable sights in San Diego as "San Diego's Icon".

- California State Building, completed October 2, 1914, which now houses the Museum of Us. The design was inspired by the church of San Diego in Guanajuato, Mexico.[69]

- Chapel of St. Francis of Assisi (south side of Fine Arts Building); now the Saint Francis Chapel operated by the Museum of Us.

- Fine Arts Building (on south side of Plaza of California), now part of the Museum of Us.

- Spreckels Organ Pavilion (dedicated December 31, 1914).

The fair left a permanent mark in San Diego in its development of Balboa Park. Up to that point, the park had been mainly open space. But with the landscaping and building done for the fair the park was permanently transformed and is now a major cultural center, housing many of San Diego's major museums. Even before the end of the first year of the expo, an organization was established to determine how the temporary buildings could be developed for museum use.[70] The exposition also led to the eventual establishment of the San Diego Zoo in the park, which grew out of abandoned exotic animal exhibitions from the Isthmus portion of the expo.[71]

During the expo, Franklin D. Roosevelt, then Assistant Secretary of the Navy, told reporters that San Diego would become a Navy port.[53] This declaration would gradually result in multiple Navy installations in and around San Diego that continue today. Shortly after the end of the expo, the Army and Marines temporarily used several empty expo buildings until nearby bases were completed.[71]

| Exposition name | Later or alternate name | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Administration Building (1915) | Gill Administration Building | (completed March 1912) now holds offices of the Museum of Us |

| Commerce & Industries Building (1915) | Canadian Building (1916); Palace of Better Housing (1935) | renamed Electrical Building and lost in a 1978 arson fire, reconstructed as the Casa de Balboa |

| Foreign Arts Building (1915) | altered and renamed House Of Hospitality[69] in 1935, reconstructed to be permanent in 1997 | |

| Varied Industries & Food Products Building (1915) | Foreign & Domestic Building (1916); Palace of Food & Beverages (1935) | 1971 reconstruction named Casa del Prado[69] |

| Montana State Building (1915) | demolished | |

| New Mexico State Building (1915) | Palace of Education (1935) | now used by Balboa Park Club |

| Home Economy Building (1915) | Pan-Pacific Building (1916) Cafe of the World (1935) | demolished; Timken Museum of Art built on site in 1965 |

| Indian Arts Building (1915) | Arts & Crafts Building (tentative); Russia & Brazil Building (1916) | rebuilt to exacting specification in 1996 as the House of Charm |

| San Joaquin Valley Building (1915) | demolished | |

| Science & Education Building (1915) | Science of Man exhibit, Palace of Science & Photography (1935) | demolished in 1964 (exhibit inspired creation of Museum of Us) |

| Southern California Counties Building (1915) | Civic Auditorium | burned down in 1925, replaced in 1933 with San Diego Natural History Museum[69] |

| Kansas State Building (1915) | Theosophical Headquarters (1916); United Nations/House of Italy | designed in the spirit of Mission San Luis Rey in Oceanside |

| Sacramento Valley Building (1915) | United States Building (1916) | replaced by San Diego Museum of Art in 1926 |

| Painted Desert (1915) | later used by military and Boy Scouts; demolished in 1946[32][72] | |

| Washington State Building (1915) | demolished |

.jpg.webp)

Later exposition and rebuilding

The California Pacific International Exposition at the same site in 1935 was so popular that some buildings were rebuilt to be made more permanent. Many buildings or reconstructed versions remain in use today, and are used by several museums and theatres in Balboa Park.

In the early 1960s destruction of a few of the buildings and replacement by modern, architecturally clashing buildings created an uproar in San Diego. In 1967, citizens formed A Committee of One Hundred to protect and preserve the park buildings.[73] They convinced the City Council to require new buildings to be built in Spanish Colonial Revival Style and worked with various government agencies to have the remaining buildings declared National Historic Landmarks in 1977.[74] In the late 1990s, the most deteriorated buildings and burned buildings were rebuilt, preserving the original style.

Centennial

The City of San Diego had planned a major observation of the 2015 centennial of the Exposition. The park institutions was to have special programming for the centennial; specific programming within the park but outside the City leaseholds.[6] The most ambitious proposal was one which would remove vehicle traffic and parking from the central Plaza de California and Plaza de Panama, using a newly constructed ramp off the Cabrillo Bridge to divert vehicles around the California Quadrangle to a parking structure behind the Organ Pavilion.[75] The proposal was controversial and was eventually dropped due to legal challenges.[76] Throughout 2015, multiple events and exhibits were held to commemorate the centennial.[77]

Exhibition map

References

- Amero (2013), p. 13

- "Table 22. Nativity of the Population for Urban Places Ever Among the 50 Largest Urban Places Since 1870: 1850 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. October 31, 2011. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- Amero (2013), p. 16

- Amero (2013), p. 17

- Pourade (1965), p. 186

- Showley, Roger (November 12, 2012). "California Tower may open to visitors". U-T San Diego. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- Amero (2013), p. 26

- Amero, Richard A. (Winter 1990). "The Making of the Panama-California Exposition, 1909–1915". 38 (1). San Diego Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 22, 2014. Retrieved June 28, 2014. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Christman (1985), p. 43

- Amero (2013), p. 34

- Amero (2013), p. 222

- Amero (2013), p. 39

- Amero (2013), p. 19

- Christman (1985), p. 16

- Montes, Gregory (Winter 1982). "Balboa Park, 1909–1911 The Rise and Fall of the Olmsted Plan". The Journal of San Diego History. 28 (1). Archived from the original on June 4, 2011.

- Harper, Hilliard (October 6, 1985). "The Happy Accident" (Fee required). Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 27, 2011.

- Smith, James R. "San Francisco's Finest World's Fair". San Francisco City Guides. Archived from the original on November 22, 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

"Hard Times, High Visions". Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley. June 10, 2009. Archived from the original on November 22, 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

"People & Events: The Panama Pacific International Exposition". American Experience. WGBH Educational Foundation. 2002. Archived from the original on November 22, 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2014. - Starr, Kevin (December 4, 1986). Americans and the California dream, 1850–1915. Oxford University Press. p. 405. ISBN 0-19-504233-6.

- Amero (2013), p. 46

- Gebhard, David (1967). "The Spanish Colonial Revival in Southern California (1895–1930)" (PDF). Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. Society of Architectural Historians. 26 (2): 131–147. doi:10.2307/988417. JSTOR 988417. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

Officer, James E. (1990). Hispanic Arizona, 1536–1856. University of Arizona Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8165-1152-5. Retrieved November 22, 2014. - Starr (1986), p. 127

- "Santa Barbara County Courthouse" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 19, 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 8, 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- Winslow, Carleton Monroe (1916). The Architecture and the Gardens of the San Diego Exposition. San Francisco: Paul Elder and Company.

- Brandes, Ray (1981). San Diego: An Illustrated History. Los Angeles: Rosebud Books. p. 129. ISBN 0-86558-006-5.

- Amero (2013), p. 35

- Amero (2013), p. 36

- Amero (2013), p. 50

- Amero (2013), p. 57

- Amero (2013), p. 48

- Amero (2013), p. 60

- Amero (2013), p. 165

- Starr (1986), p. 129

- Björn A. Schmidt (November 2016). Visualizing Orientalness: Chinese Immigration and Race in U.S. Motion Pictures, 1910s-1930s. Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar. p. 127. ISBN 978-3-412-50532-5.

Krystyn R. Moon (2005). Yellowface: Creating the Chinese in American Popular Music and Performance, 1850s-1920s. Rutgers University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-8135-3507-4.

Panama-California Exposition Commission (1915). Official Guide Book of the Panama-California Exposition, Giving in Detail, Location and Description of Buildings, Exhibits and Concessions, with Floor Plans of the Buildings and Exterior Views ...: San Diego, California, January 1 to December 31, 1915. National views Company. p. 39. - Amero (2013), p. 47

- "History". Balboa Park Online Collaborative. Balboa Park. Archived from the original on November 22, 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

"History of the California Building in Balboa Park". San Diego History Center. Balboa Park Online Collaborative. Archived from the original on November 22, 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

Michelle, Tom Grimm (October 7, 1979). "Growing Years of Balboa Park". Los Angeles Times. - Pourade (1965), p. 198

- Amero (2013), p. 27

- Amero (2013), p. 51

- Hurley, Morgan M. (June 8, 2012). "Restored historic streetcar showcased at Trolley Barn Park". San Diego Uptown News. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- Amero (2013), p. 56

- Showley, Roger (November 15, 2012). "Balboa Park's 'Electriquettes' may return". U-T San Diego. Archived from the original on November 28, 2014.

- Christman (1985), p. 46

- Amero (2013), p. 148

- Amero (2013), p. 49

- Amero (2013), p. 62

- Amero (2013), p. 71

- Christman (1985), p. 45

- Pourade (1965), p. 183

- Amero (2013), p. 53

- Amero (2013), p. 54

- Pourade (1965), p. 193

- Pourade (1965), p. 195

- Amero (2013), p. 85

- Pourade (1965), p. 197

- Pourade (1965), p. 194

- Amero (2013), p. 101

- Starr (1986), p. 128

- Pourade (1965), p. 199

- Amero (2013), p. 133

- Amero (2013), p. 106

- Amero (2013), p. 108

- Amero (2013), p. 117

- Amero (2013), p. 114

- Reynolds, Christopher (3 January 2015). "How San Diego's, San Francisco's rival 1915 expositions shaped them". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- Amero (2013), p. 116

- Amero (2013), p. 127

- Showley (2000), p. 94

- Pourade (1965), p. 218

- Carolyn Pitts (July 19, 1977), National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Balboa Park (PDF), National Park Service, retrieved 2009-06-22 and Accompanying 18 photos, undated (6.37 MB)

- Amero (2013), p. 99

- Amero (2013), p. 139

- Adkins, Lynn (Spring 1983). "Jesse L. Nusbaum and the Painted Desert in San Diego". 29 (2). San Diego Historical Society. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved January 3, 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "About Us". Committee of One Hundred. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- "National Historic Landmark Program – Balboa Park". National Park Service. Archived from the original on December 13, 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- Showley, Roger (August 31, 2010). "Plaza plan for Balboa Park unveiled". U-T San Diego. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- Showley, Roger (February 5, 2013). "Jacobs exits Balboa Park plan". U-T San Diego. Archived from the original on November 28, 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- Deery, Danielle Susalla (7 August 2015). "Balboa Park Centennial Exhibitions at 11 San Diego Museums". San Diego Museum Council. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

"Panama-California Exposition Centennial Celebration Events". Save Our Heritage Organization. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Quach, Hoa (31 January 2015). "Guide: Balboa Park Centennial Celebration". KPBS. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Richard, Terry (4 February 2015). "San Diego's Balboa Park decked out to celebrate centennial of 1915 Panama-California Exposition". The Oregonian. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- Bibliography

- Amero, Richard W. (2013). Balboa Park and the 1915 Exposition (1st ed.). Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-62619-345-1.

- Christman, Florence (1985). The Romance of Balboa Park (4th ed.). San Diego: San Diego Historical Society. ISBN 0-918740-03-7.

- Pourade, Richard F. (1965). Gold in the Sun (1st ed.). San Diego: The Union-Tribune Publishing Company. ISBN 0-913938-04-1.

- Starr, Raymond G. (1986). San Diego: A Pictorial History (1st ed.). Norfolk: The Donning Company. ISBN 0-89865-484-X.

Further reading

- The Official Guide Book of the Panama California Exposition San Diego 1915

- San Diego's Balboa Park by David Marshall, AIA, Arcadia Publishing, 2007, ISBN 978-0-7385-4754-1

- Phoebe S. Kropp, California Vieja: Culture and Memory in a Modern American Past. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006. ISBN 0-520-24364-1

- The San Diego World's Fairs and Southwestern Memory, 1880–1940 by Matthew F. Bokovoy, University of New Mexico Press, 2005. ISBN 0-8263-3642-6

- Redman, Samuel J. Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 2016. ISBN 978-0-674-66041-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Panama-California Exposition. |

- "The Making of the Panama-California Exposition, 1909–1915", The Journal of San Diego History 36:1 (Winter 1990), by Richard W. Amero

- "The Southwest on Display at the Panama-California Exposition, 1915", The Journal of San Diego History 36:4 (Fall 1990), by Richard W. Amero

- "Safeguarding the Innocent: Travelers' Aid at the Panama-California Exposition, 1915", The Journal of San Diego History 61:3&4 (Summer/Fall 2015), by Eric C. Cimino

- Panama-California Exposition Digital Archive