Parfait-Louis Monteil

Parfait-Louis Monteil (1855 – 29 September 1925) was a French colonial military officer and explorer who made an epic journey in West Africa between 1890 and 1892, travelling east from Senegal to Lake Chad, and then north across the Sahara to Tripoli.[1]

Early career

Monteil was the older brother of Charles Monteil (1871–1949), who became a distinguished ethologist.[2] Monteil was a graduate of the École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr. He served in Senegal, where his duties included cartographical surveys.[3] In 1884 he was made a member of the Société de géographie de Paris and in 1886 became an officer of the society.[4][5] He was influenced by the former governor of Senegal, Louis Faidherbe, whom he regularly visited in his apartment (where Faidherbe was confined by paralysis) in the middle 1880s.[6][7]

Monteil served in the French protectorate of Annam, now part of Vietnam, from 1886 to 1888.[3] He then spent time investigating a railway project to link Bafoulabé and Bamako in Senegal, before launching on his great journey across West Africa in 1890.[1]

Political background

France, Britain, Germany, Portugal and Italy came to a broad agreement on the way in which they would divide up the continent of Africa at the 1884–1885 Berlin Conference. France gained primacy in the bulk of West Africa from Algeria and Tunisia south across the Sahara and the Sahel into the Sudanian Savanna. The other powers could extend their coastal colonies north from the Gulf of Guinea into the interior. In the case of Britain, these colonies included the Gambia, Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast (now Ghana), the Lagos colony and the territory claimed by the Royal Niger Company.[8]

On 5 August 1890 the British and French concluded an agreement to clarify the boundary between French West Africa and what would become Nigeria. Britain would acquire all territories up to and including the Sokoto Caliphate, while the French would take the lands further to the north. However, they did not know the extent of the Sokoto Caliphate. Monteil was given charge of an expedition to discover its northern limits.[3]

From Senegal to Tripoli via Chad

Colonel Monteil and a small party of Frenchmen arrived in Dakar in September 1890. He traveled by railway up the coast to St. Louis where he hired bearers and tirailleurs. He continued his journey up the Sénégal River by steamer, arriving on 18 October 1890 at Kayes, where he bought equipment and horses. Monteil reached Ségou on the upper Niger River on 14 December, the last outpost of the French in the Sudan. The countries to the east were known to be Moslem, were rumored to be rich in gold, slaves and ivory, but were uncharted territory to Europeans.[3]

Monteil set out eastwards, generally obtaining a friendly reception and signing treaties of friendship, although suffering from heat, mosquitos and lack of drinking water.[3] The Almami of San signed a peace treaty placing the town under French protection. Monteil praised the caravan center at San, saying that transactions could be made in total security, with no duties levied on imports, exports or sales.[9]

Entering what is now Burkina Faso, Monteil wanted Wobogo, the Mogho Naba of Mossy and ruler of Ouagadougou, to agree to a French protectorate. Wobogo refused to receive him, and he was forced to make a hurried departure.[10][11] He reached Dori, the capital of Liptako, on 22 May 1891, at a time when the Amiirou, Amadou Iisa, was dying, and became involved in a dispute over succession. Monteil started to negotiate a treaty with the followers of Issa, son of the Amiirou and next in line, but the Amiirous's nephew Sori managed to gain the support needed to become the next ruler.[12]

In June Monteil went on to Sebba, capital of Yagha, where after a considerable payment to the "greedy" ruler another treaty was agreed. From there he travelled via Torodi to Say, a large commercial town on the Niger River, and then onward to Sokoto via the Argungu triangle. He observed that the Kebbi Argungu Emirate was independent of the Sokoto Caliphate. This later became a point of dispute between the French and British authorities. Further, he found little evidence that the Royal Niger Company was present in the region as claimed, apart from some trading posts in the Gwandu Emirate to the south of Argundu.[3]

Monteil was welcomed by the Caliph of Sokoto, Abd ar-Rahman dan Abi Bakar, who at the time was engaged in a war with the Emir of Argungu. He signed a treaty with the Caliph on 28 October 1891, and presented him with silks, brocades, embroidered caftans and money. He said the state of the Caliphate was precarious when he visited, but may have overestimated the combined effects of the war and the recent accession of an unpopular ruler. Shortly after Monteil left, Sokoto defeated Argungu.[3]

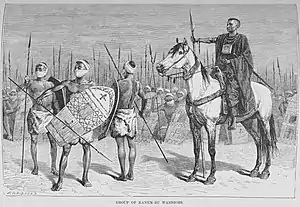

Monteil journeyed from Sokoto to the important trading center of Kano, then via Hadejia to Lake Chad.[3] On 9 April 1892 he reached Kuka on the shore of the lake, where he was met by a group of 150 cavalrymen arrayed in colorful costumes, with their horses dressed in padded caparisons. The horsemen charged him with spears leveled, stopping at the last minute, a sign of respect and also a test of courage. He exchanged courtesies with the Sultan of Bornu, and was his guest for several months while he explored the country around the lake – and while the Sultan tried to extract gifts in exchange for a safe conduct. When finally allowed to depart, he traveled northward across the Sahara to Tripoli, reaching the Mediterranean on 10 December 1892. His journey had done much to clarify for Europeans, and for France in particular, the geography and politics of the region.[13] Within 15 years, almost all the territory Monteil had visited was firmly under colonial control.[14]

Later career

After Monteil's return to France, in 1893 the Société de géographie awarded him the Grand Gold Medal for his book recording the journey.[15] The successful expedition across West Africa impressed the statesman Théophile Delcassé, who took Monteil to meet the President of France, Sadi Carnot on 4 May 1893. Carnot wanted Monteil to undertake an expedition to Fashoda on the upper Nile, but on 30 May Delcassé sent him to the French Congo to reinforce Haut-Oubangui (now the Central African Republic) against Belgian intrusions.[16] He arrived at the port of Luango on 24 August 1894, planning to travel first to Ubangi and then onwards to the Nile. Before starting for the interior, however, he was urgently reassigned to the Ivory Coast to help deal with the threat from the imam-warrior Samori Ture.[17] In September 1894 he directed an expedition into Baoulé country in the Ivory Coast, reaching Tiassalé in December before being turned back by fierce opposition north of the city.[18] The Governor of French Sudan, Albert Grodet, took some of the blame for the fiasco.[19]

Later, Monteil tried without success to enter politics, and was involved in colonization of the south of Tunisia.[1] He died at Herblay, Seine-et-Oise in 1925.[20]

Bibliography

- Parfait-Louis Monteil (1882). Voyage d’exploration au Sénégal (Voyage of exploration in Senegal) (in French).

- Parfait-Louis Monteil (1884). En France et aux colonies, vade-mecum de l'officier d'infanterie de marine (Handbook of an officer of the marine infantry) (in French). Baudoin et Cie.

- Parfait-Louis Monteil (1894). De Saint-Louis a Tripoli par le Lac Tchad, Voyage au Travers du Soudan et du Sahara Accompli Pendant les Années 1890-91-92. (From Saint-Louis to Tripoli via Lake Chad ...) (in French). Paris: Félix Alcan.

- Heinrich Barth; Paul Voulet; Parfait-Louis Monteil (1897). Textes anciens sur le Burkina (Ancient texts on Burkina) (in French).

- Parfait-Louis Monteil (1902). Une page d’histoire coloniale : la colonne de Kong, 1895 (A page of colonial history: The colony of Kong, 1895) (in French).

- Parfait-Louis Monteil (1924). Quelques feuillets de l’histoire coloniale (Some pages of colonial history) (in French).

Notes

- Lanhers 1950

- Dulucq 2009, p. 169.

- Hirshfield 1979, pp. 37ff

- SDG 1885, pp. 73

- MEN 1886, pp. 282

- Bingen, Robinson & Staatz 2000, pp. 38

- Marcus & Spaulding 1998, pp. 97

- Crowe 1942

- Mann 2006, pp. 26

- Englebert 1999, pp. 18

- Abaka 2004

- Benjaminsen & Lund 2001, pp. 41

- Lengyel 2007, pp. 170ff

- Oliver, Fage & Sanderson 1985, p. 257ff

- Pinta 2006, pp. 31

- Kalck 2005, pp. 141

- Imperato 2001, pp. 161

- Prater 2005

- Klein 1998, p. 113.

- Larousse 1963, pp. 487

References

- Abaka, Edmund (2004). "Collaboration as Resistance". In Kevin Shillington (ed.). Encyclopedia of African History. 1 A–G. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-48386-2. OCLC 62895404. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- Benjaminsen, Tor Arve; Lund, Christian (2001). Politics, property and production in the West African Sahel: understanding natural resources management. Nordic Africa Institute. ISBN 91-7106-476-1. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- Bingen, R. James; Robinson, David; Staatz, John M. (2000). Democracy and development in Mali. MSU Press. ISBN 978-0-87013-560-6. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- Crowe, Sybil E. (1942). The Berlin West African Conference, 1884–1985. New York: Longmans, Green. ISBN 0-8371-3287-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dulucq, Sophie (2009), Ecrire l'histoire de l'Afrique à l'époque coloniale: XIXe-XXe siècles (in French), KARTHALA Editions, ISBN 978-2-8111-0290-6, retrieved 2018-06-18

- Englebert, Pierre (1999). Burkina Faso: Unsteady Statehood In West Africa. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3680-5. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- Hirshfield, Claire (1979). The diplomacy of partition: Britain, France, and the creation of Nigeria, 1890–1898. Springer. ISBN 90-247-2099-0. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- Imperato, Pascal James (2001). Quest for the Jade Sea: Colonial Competition Around an East African Lake. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-2792-X. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- Kalck, Pierre (2005). "Monteil, Colonel Parfait". Historical dictionary of the Central African Republic. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4913-5. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- Klein, Martin A. (1998-07-28), Slavery and Colonial Rule in French West Africa, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-59678-7, retrieved 2018-06-17

- Lanhers, Y. (1950). "Fonds colonel Monteil (1885–1940)" (PDF) (in French). Les Archives nationales de France. 66 AP 1 à 18. Retrieved 2010-10-10. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Larousse (1963). "Monteil (Partfait Louis)". Grand Larousse encyclopédique en dix volumes (in French). 7: Mali–Orly. Librairie Larousse.

- Lengyel, Emil (2007). Dakar — Outpost of Two Hemispheres. READ BOOKS. ISBN 1-4067-6146-X. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- Marcus, Harold G.; Spaulding, Jay (1998). Melvin Eugene Page (ed.). Personality and political culture in modern Africa: studies presented to Professor Harold G. Marcus. Boston University papers on Africa. 9. African Studies Center, Boston University. ISBN 978-0-915118-16-8.

- Mann, Gregory (2006). Native sons: West African veterans and France in the twentieth century. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3768-1. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- Ministère de l'éducation nationale, France (1886). Recueil des lois et actes de l'instruction publique (in French). Delalain frères. Retrieved 2010-10-11.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Oliver, Roland; Fage, J. D.; Sanderson, G. N. (1985). The Cambridge history of Africa: From 1870 to 1905. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22803-4. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- Pinta, Pierre (2006). La Libye (in French). KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 2-84586-716-6. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- Prater, Robert Hill (2005-10-19). Seedtime and Harvest: Christian Mission and Colonial Might in Côte d’Ivoire (1895–1920) (PDF) (Thesis). Friedrich-Alexander-Universität. URN urn:nbn:de:bvb:29-opus-2621. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 9, 2012. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- Société de géographie (France) (1885). Liste des membres. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

Further reading

- Henri Labouret (1937). Monteil: Explorateur et soldat (in French). Paris: Berger-Levrault.