Lake Chad

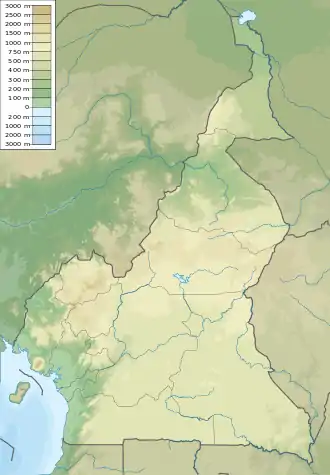

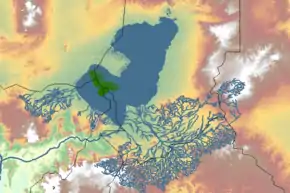

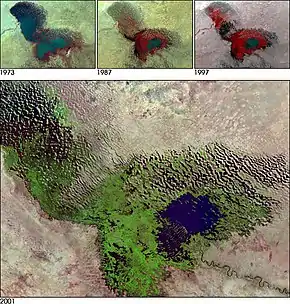

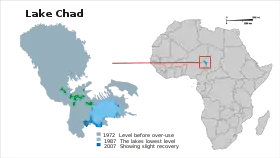

Lake Chad (French: Lac Tchad) is a historically large, shallow, endorheic lake in central Africa, which has varied in size over the centuries. According to the Global Resource Information Database of the United Nations Environment Programme, it shrank by as much as 95% from about 1963 to 1998. The lowest area was in 1986, at 279 km2 (108 sq mi),[10] but "the 2007 (satellite) image shows significant improvement over previous years."[11] Lake Chad is economically important, providing water to more than 30 million people living in the four countries surrounding it (Chad, Cameroon, Niger, and Nigeria) on the central part of the Sahel.[12] It is the largest lake in the Chad Basin.

| Lake Chad | |

|---|---|

Photograph taken by Apollo 7, October 1968 | |

Lake Chad  Lake Chad | |

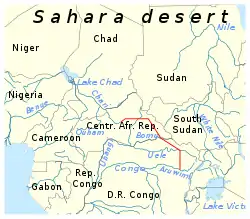

Map of lake and surrounding region | |

| Coordinates | 13°0′N 14°30′E |

| Lake type | Endorheic |

| Primary inflows | Chari River |

| Primary outflows | Soro and Bodélé depressions |

| Basin countries | Chad, Cameroon, Niger, Nigeria |

| Surface area | 1,540 km2 (590 sq mi) (2020)[1] |

| Average depth | 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in)[2] |

| Max. depth | 11 m (36 ft)[3] |

| Water volume | 6.3 km3 (1.5 cu mi)[4] |

| Shore length1 | 650 km (400 mi) |

| Surface elevation | 278 to 286 metres (912 to 938 ft) |

| References | [5] |

| Official name | Lac Tchad |

| Designated | 17 June 2001 |

| Reference no. | 1072[6] |

| Official name | Partie tchadienne du lac Tchad |

| Designated | 14 August 2001 |

| Reference no. | 1134[7] |

| Official name | Lake Chad Wetlands in Nigeria |

| Designated | 30 April 2008 |

| Reference no. | 1749[8] |

| Official name | Partie Camerounaise du Lac Tchad |

| Designated | 2 February 2010 |

| Reference no. | 1903[9] |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

Geography and hydrology

The freshwater lake is located in the Sahelian zone of West-central Africa. It is located in the interior basin which used to be occupied by a much larger ancient sea sometimes called Mega Chad. The lake is historically ranked as one of the largest lakes in Africa. Its surface area varies by season as well as from year to year. Lake Chad is mainly in the far west of Chad, bordering on northeastern Nigeria.

The Chari River, fed by its tributary the Logone, provides over 90% of the lake's water, with a small amount coming from the Yobe River in Nigeria/Niger. Despite high levels of evaporation, the lake is fresh water. Over half of the lake's area is taken up by its many small islands (including the Bogomerom Archipelago), reedbeds and mud banks, and a belt of swampland across the middle divides the northern and southern halves. The shorelines are largely composed of marshes. The Lake Chad flooded savannas surround the lake, including permanently and seasonally-flooded grasslands, savannas, and woodlands.

Because Lake Chad is very shallow—only 10.5 metres (34 ft) at its deepest—its area is particularly sensitive to small changes in average depth, and consequently it also shows seasonal fluctuations in size. Lake Chad has the Bahr el-Ghazal (wadi in Chad) outlet, but its waters percolate into the Soro and Bodélé depressions. The climate is dry most of the year, with moderate rainfall from June through September.

History

Lake Chad gave its name to the country of Chad. The name Chad is derived from the Kanuri word "Sádǝ" meaning "large expanse of water".[13] The lake is the remnant of a former inland sea, paleolake Mega-Chad, which existed during the African humid period. At its largest, sometime before 5000 BC, Lake Mega-Chad was the largest of four Saharan paleolakes, and is estimated to have covered an area of 1,000,000 km2 (390,000 sq mi), larger than the Caspian Sea is today, and may have extended as far northeast as within 100 km (62 mi) of Faya-Largeau.[14][15] At its largest extent the river Mayo Kébbi represented the outlet of the paleolake Mega-Chad, connecting it to the Niger River and the Atlantic.[16] This lowest point on the basin's rim now stands at about 320 meters above sea level, meaning that even if Lake Chad were to refill to its largest extent it would still be at the most only about 50 meters deep. The presence of African manatees in the inflows of Lake Chad is an evidence of the overflow history, since the manatee is otherwise only in rivers connected to the Atlantic Ocean (i.e. it is not possible that it evolved separately in an enclosed Chad Basin). The grand scale of the Mayo Kébbi river course is also evidence of earlier overflow from Mega-Chad; the upstream catchment of today is far too small to have dug such a large channel.

Romans reached the lake in the first century of their empire. During the time of Augustus Lake Chad was still a huge lake and two Roman expeditions were performed in order to reach it: Septimius Flaccus and Julius Maternus reached the "lake of hippopotamus[17] (as the lake was called by Claudius Ptolemaeus). They moved from coastal Tripolitania and passed near the Tibesti mountains. Both expeditions passed through the territory of the Garamantes, and were able to leave a small garrison on the "lake of hippopotamus and rhinoceros" after three months of travel in desert lands.

Lake Chad was first surveyed from shore by Europeans in 1823, and it was considered to be one of the largest lakes in the world then.[18] In 1851, a party including the German explorer Heinrich Barth carried a boat overland from Tripoli across the Sahara Desert by camel and made the first European waterborne survey.[19] British expedition leader James Richardson died just days before reaching the lake.

In Winston Churchill's book The River War: An Account of the Reconquest of the Sudan, published in 1899, he specifically mentions the shrinking of Lake Chad. He writes:

Altogether France has enough to occupy her in Central Africa for some time to come: and even when the long task is finished, the conquered regions are not likely to be of great value. They include the desert of the Great Sahara and wide expanses of equally profitless scrub or marsh. Only one important river, the Shari, flows through them, and never reaches the sea: and even Lake Chad, into which the Shari flows, appears to be leaking through some subterranean exit, and is rapidly changing from a lake into an immense swamp.[20]

Lake Chad has shrunk considerably since the 1960s, when its shoreline had an elevation of about 286 metres (938 ft) above sea level[21] and it had an area of more than 26,000 square kilometres (10,000 sq mi), making its surface the fourth largest in Africa. An increased demand on the lake's water from the local population has likely accelerated its shrinkage over the past 40 years.[2]

The size of Lake Chad greatly varies seasonally with the flooding of the wetlands areas. In 1983, Lake Chad was reported to have covered 10,000 to 25,000 km2 (3,900 to 9,700 sq mi),[3] had a maximum depth of 11 metres (36 ft),[3] and a volume of 72 km3 (17 cu mi).[3]

By 2000, its extent had fallen to less than 1,500 km2 (580 sq mi). A 2001 study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research blamed the lake's retreat largely on overgrazing in the area surrounding the lake, causing desertification and a decline in vegetation.[22] The United Nations Environment Programme and the Lake Chad Basin Commission concur that at least half of the lake's decrease is attributable to shifting climate patterns. UNEP blames human water use, such as inefficient damming and irrigation methods, for the rest of the shrinkage.[23] As late as December 2014, Lake Chad was still sufficient in size and volume such that boats could capsize or sink. The European Space Agency has recently presented data showing an actual increase in lake extent of Lake Chad between the years of 1985 to 2011.[24]

Referring to the floodplain as a lake may be misleading, as less than half of Lake Chad is covered by water through an entire year. The remaining sections are considered as wetlands.

Lake Chad's volume of 72 km3 (17 cu mi)[3] is very small relative to that of Lake Tanganyika (18,900 km3 (4,500 cu mi)), and Lake Victoria (2,750 km3 (660 cu mi)), African lakes with similar surface areas.

Flora

The lake is home to more than 44 species of algae. In particular it is one of the world's major producers of wild spirulina. The lake also has large areas of swamp and reedbeds. The floodplains on the southern lakeshore are covered in wetland grasses such as Echinochloa pyramidalis, Vetiveria nigritana, Oryza longistaminata, and Hyparrhenia rufa.

Fauna

The entire Lake Chad basin holds 179 fish species, of which more than half are shared with the Niger River Basin, about half are shared with the Nile River Basin, and about a quarter are shared with the Congo River Basin.[25] Lake Chad itself holds 85 fish species.[25] Of the 25 endemics in the basin, only Brycinus dageti is found in the lake itself,[25] and it is perhaps better treated as a dwarf subspecies of Brycinus nurse.[26] This relatively low species richness and virtual lack of endemic fish species contrasts strongly with other large African lakes, such as Victoria, Tanganyika and Malawi.[27]

There are many floating islands in the lake. It is home to a wide variety of wildlife, including elephants, hippopotamus, crocodile (all in decline), and large communities of migrating birds including wintering ducks, ruff (Philomachus pugnax) and other waterfowl and shore birds. There are two near-endemic birds in the region, the river prinia (Prinia fluviatilis) and the rusty lark (Mirafra rufa). The shrinking of the lake is threatening nesting sites of the black-crowned crane (Balearica pavonina pavonina). During the wet season, fish move into the mineral-rich lake to breed and find food. Carnivores such as the Central African cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus soemmeringii), the striped hyena (Hyaena hyaena) and the caracal (Felis caracal) used to inhabit areas surrounding the lake.[28]

Threats and preservation

There is some debate over the mechanisms causing the lake's disappearance. The leading theory, which is most often cited by the UN, is that the unsustainable usage of the lake by both governments and local communities has caused the lake to be over-used, not allowing it to replenish.[29]

Recently, however, an additional theory is gaining traction. This states that European air pollution had shifted rainfall patterns farther south, thereby making the region drier and not allowing the lake to replenish. Since the implementation of new regulations in the EU concerning air pollutants, much of this rainfall is now beginning to return, thereby explaining the small improvements observed since 2007.[30]

The only protected area is the Lake Chad Game Reserve, which covers half of the area next to the lake that belongs to Nigeria. The whole lake has been declared a Ramsar site of international importance.[31]

Speaking at the United Nations 73rd General Assembly, the President of Nigeria urged the international community to assist in combatting the root causes of conflict surrounding the Lake Chad Endorheic basin. Recent violence in the region has been attributed to competition between farmers and herders seeking irrigation for crops and watering of herds respectively.[32]

In September 2020, in order to explore oil and mining opportunities in the region, Chad's tourism and culture minister wrote to UNESCO, the body which awards the world heritage designation, asking to "postpone the process of registering Lake Chad on the world heritage list".[33]

Management

Plans to divert the Ubangi River into Lake Chad were proposed in 1929 by Herman Sörgel in his Atlantropa project and again in the 1960s. The copious amount of water from the Ubangi would revitalize the dying Lake Chad and provide livelihood in fishing and enhanced agriculture to tens of millions of central Africans and Sahelians. Interbasin water transfer schemes were proposed in the 1980s and 1990s by Nigerian engineer J. Umolu (ZCN scheme) and Italian firm Bonifica (the Transaqua canal scheme).[34][35][36][37]

In 1994, the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC) proposed a similar project, and at a March 2008 summit, the heads of state of the LCBC member countries committed to the diversion project.[38] In April 2008, the LCBC advertised a request for proposals for a World Bank-funded feasibility study.[39] Neighboring countries have agreed to commit resources to restoring the lake, notably Nigeria.[40][41]

The CIMA (Canada) proposed project can be used as an inland waterway, as it uses the same water flow (100 m3/s) as the Moscow Canal.

Local impact

The dwindling of the lake has had devastating impacts on Nigeria.[42] Because of the way it has shrunk dramatically in recent decades, the lake has been labeled an ecological catastrophe by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.[43] Human population expansion and unsustainable human water extraction from Lake Chad have caused several natural species to be stressed and threatened by declining lake levels. For example, the decline or disappearance of the endangered painted hunting dog has been noted in the Lake Chad area.[44]

The shrinking of the lake has also caused several different conflicts to emerge, as the countries bordering Lake Chad argue over the rights to the remaining areas of water. Along with international conflicts, violence between countries is also increasing among the lake's dwellers. Farmers and herders want the water for their crops and livestock and are constantly diverting the water,[45] while the lake's fishermen want water diversion slowed or halted in order to prevent continuing decline in water levels resulting in further strain on the lake's fish.[46] Furthermore, populations of birds and other animals in the area are threatened, including those that serve as important sources of food for the local human population.

See also

- Aïr Mountains

- Aral Sea

- Daphnia barbata

- Lake Ptolemy

- List of drying lakes

- List of lakes

- Neolithic Subpluvial

- Romans in Sub-Saharan Africa

- The Sudd, an immense marshland in neighboring South Sudan along the Nile and Bahr-el-Ghazal

References

- Odada, Oyebande & Oguntola 2020.

- WaterNews 2008.

- World Lakes Database 1983.

- World Lakes Database 2020.

- Odada, Oyebande & Oguntola 2005.

- "Lac Tchad". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "Partie tchadienne du lac Tchad". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "Lake Chad Wetlands in Nigeria". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "Partie Camerounaise du Lac Tchad". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- Umar, I.A., (2018): Modelling of water cycle regime of Lake Chad using GIS and remote sensing for decadal periods. Unpublished BSc Project. University of Maiduguri, Borno, Nigeria

- United Nations 2007.

- AllAfrica 2012.

- Room 1994.

- Drake & Bristow 2006, pp. 901, 910.

- Stewart 2009, Chapter: Dead and dying seas.

- Leblanc et al. (2006). "Reconstruction of megalake Chad using shuttle radar topographic mission data". Palaeogeography, palaeoclimatology, palaeoecology 239, pp. 16–27 ISSN 0031-0182 1872-616X

- Johnston, H. H. (1 August 1910). "Lake Chad 1". Nature. 84 (2130): 244–245. Bibcode:1910Natur..84..244J. doi:10.1038/084244a0. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 8682184.

- Funk & Wagnalls 1973.

- Steve Kemper (2012). Labyrinth of Kingdoms: 10,000 Miles Through Islamic Africa. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0393079661.

- Winston Churchill (1902). The River War: An Account of the Reconquest of the Sudan. Retrieved 31 May 2017 – via www.gutenberg.org.

- Drake & Bristow 2006, Figures 1, 10.

- Coe & Foley 2001.

- CNN 2007.

- http://www.esa.int/var/esa/storage/images/esa_multimedia/images/2013/10/lake_chad_water_extent_increase/13371177-1-eng-GB/Lake_Chad_water_extent_increase.gif

- Hughes & Hughes 1992.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2011). "Brycinus nurse" in FishBase. May 2011 version.

- Nelson 2006.

- "Lake Chad flooded savanna". WWF World Wildlife.org. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- "Lake Chad: almost gone". Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- "Lake Chad's receding waters linked to European air pollution – Climate Home – climate change news". Climate Home – climate change news. 18 June 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- "Lake Chad Wetlands in Nigeria | Ramsar Sites Information Service". rsis.ramsar.org. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "UN Live United Nations Web TV - Search Results for "President of Nigeria, General Assembly" - Nigeria – President Addresses General Debate, 73rd Session".

- Gouby, Mélanie (24 September 2020). "Chad halts lake's world heritage status request over oil exploration". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Pearce 1991.

- Umolu 1990, pp. 218–262.

- Chapman & Baker 1992.

- Umolu 1994, Section X.

- Voice of America 2008.

- "Encyclopedia Britannica". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- "Africa's vanishing Lake Chad". Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- "Nigeria Contributes $5m to Restore Receding Lake Chad, Articles – THISDAY LIVE". Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- Damilola Oyedele (11 May 2017). "The dwindling lake". D+C, development and cooperation. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- Voice of America 2009.

- Hogan 2009.

- "Lake Chad: Inhabitants adapt to lower water levels". sciencedaily.com. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- "Case study on river management: Lake Chad". Retrieved 13 February 2018.

Sources

- Braun, David (February 2010). "Lake Chad to be fully protected as international wetlands". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010.

- Chapman, Graham; Baker, Kathleen M. (1992). The changing geography of Africa and the Middle East. Routledge.

- CNN (18 June 2007). "Climate change and diminishing desert resources". Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- Coe, Michael T.; Foley, Jonathan A. (2001). "Human and natural impacts on the water resources of the Lake Chad basin". Journal of Geophysical Research. 106 (D4): 3349–3356. Bibcode:2001JGR...106.3349C. doi:10.1029/2000JD900587.

- Drake, Nick; Bristow, Charlie (2006). "Shorelines in the Sahara: geomorphological evidence for an enhanced monsoon from palaeolake Megachad" (PDF). The Holocene. 16 (6): 901–911. Bibcode:2006Holoc..16..901D. doi:10.1191/0959683606hol981rr. S2CID 128565786.

- Funk & Wagnalls New Encyclopedia. Funk & Wagnalls, Inc. 1973.

- Hassan, Tina (2012). "Nigeria: Helping to Save Lake Chad". All Africa.

- Hogan, C. Michael (2009). Stromberg, N. (ed.). "Painted Hunting Dog: Lycaon pictus". GlobalTwitcher.com. Archived from the original on 9 December 2010.

- Hughes, R. H.; Hughes, J. S. (1992). A Directory of African Wetlands. IUCN. ISBN 978-2-88032-949-5.

- Nelson, J. S. (2006). Fishes of the World (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-471-25031-9.

- Odada, Eric O.; Oyebande, Lekan; Oguntola, Johnson A. (2005). "Lake Chad: Experiences and Lessons Learned Brief" (PDF). Managing lakes and their Basins for Sustainable Use. International Lake Environment Committee (ILEC) Foundation. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- Pearce, Fred (23 March 1991). "Africa at a watershed (Ubangi – Lake Chad Inter-basin transfer)". New Scientist (1761).

- Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). "National Geographic's Strange Days on Planet Earth: Glossary". Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- Room, Adrian (1994). African Placenames. McFarland and Company. ISBN 978-0-89950-943-3.

- Stewart, Robert (28 July 2009). "Dustiest places on Earth—dead and dying seas". Environmental Science in the 21st Century. A New Online Environmental Science Book for College Students. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- Umolu, Jerome C. (1990). "Macro Perspectives for Nigeria's Water Resources Planning". Proceedings of the First Biennial National Hydrology Symposium, Maiduguri, Nigeria: 218–262.

- Umolu, Jerome C. (1994). "Combating Climate Induced Water And Energy Deficiencies in West Central Africa: hydro/energy interconnections". Archived from the original on 26 May 2011.

- "Atlas of Our Changing Environment". United Nations Environment Programme. 2007.

- "African Leaders Team Up to Rescue Lake Chad". Voice of America. 28 March 2008. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- "Experts Look For Ways to Save Lake Chad". Voice of America. 11 November 2009. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- "Vanishing Lake Chad—a water crisis in central Africa". WaterNews. 24 June 2008. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- "Lake Chad". World Lakes Database. International Lake Environment Committee (ILEC). 1983. Archived from the original on 6 February 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lake Chad. |

- Bibliography on Water Resources and International Law Peace Palace Library

- International Cooperation and Sustainable Water Management of the Waters of the Lake Chad/ by Moustapha Abakar Malloumi

- The Encyclopedia of Earth: Lake Chad flooded savanna

- Information on, and a map of, Chad's watershed.

- Map of the Lake Chad basin at Water Resources eAtlas.

- Article on the disappearing lake in The Guardian.

- Leblanc, Marc; Favreau, Guillaume; Maley, Jean; Nazoumou, Yahaya; Leduc, Christian; Stagnitti, Frank; Van Oevelen, Peter J.; Delclaux, François; Lemoalle, Jacques (2006). "Reconstruction of Megalake Chad using Shuttle Radar Topographic Mission data". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 239 (1–2): 16–27. Bibcode:2006PPP...239...16L. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2006.01.003.

- Lakes become deserts: The story of Lake Chad – patriotdirect.org