Pelican eel

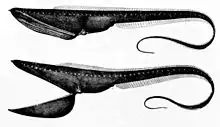

The pelican eel (Eurypharynx pelecanoides) is a deep-sea eel rarely seen by humans, though it is occasionally caught in fishing nets. It is the only known member of the genus Eurypharynx and the family Eurypharyngidae. It belongs to the "saccopharyngiforms", members of which were historically placed in their own order, but are now considered true eels in the order Anguilliformes.[2] The pelican eel has been described by many synonyms, yet nobody has been able to demonstrate that more than one species of pelican eel exists.[3] It is also referred to as the gulper eel (which can also refer to members of the related genus Saccopharynx), pelican gulper, and umbrella-mouth gulper.[4] The specific epithet pelecanoides refers to the pelican, as the fish's large mouth is reminiscent of that of the pelican.

| Pelican eel | |

|---|---|

| |

| The mouth of the pelican eel can open wide enough to swallow prey much larger than the eel itself. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Anguilliformes |

| Family: | Eurypharyngidae Gill, 1883 |

| Genus: | Eurypharynx Vaillant, 1882 |

| Species: | E. pelecanoides |

| Binomial name | |

| Eurypharynx pelecanoides Vaillant, 1882 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Gastrostomus pacificus | |

.jpg.webp)

Description

Pelican eel specimens can be hard to describe, as they are so fragile that they become damaged when recovered from the immense pressure of the deep sea.[5] The pelican eel's most notable feature is its large mouth, which is much larger than its body. The mouth is loosely hinged, and can be opened wide enough to swallow a fish much larger than the eel itself. The pouch-like lower jaw resembles that of a pelican, hence its name. The lower jaw is hinged at the base of the head, with no body mass behind it, making the head look disproportionately large. Its jaw is so large that it is estimated to be about a quarter of the total length of the eel itself.[6] When it feeds on prey, water that is ingested is expelled via the gills.[7]

The pelican eel is very different in appearance from typical eels. It lacks pelvic fins, swim bladders, and scales. Its muscle segments have a "V-shape", while other fish have "W-shaped" muscle segments.[7] The pelican eel has an aglomerular kidney that is thought to have a role in maintaining the gelatinous substance filling the "lymphatic spaces" that are found around the vertebrae. It has been hypothesized that these gelatinous substance filled "lymphatic spaces" could function in a similar way to a swim bladder.[8] Unlike many other deep sea creatures, it has very small eyes. It is believed that the eyes evolved to detect faint traces of light rather than form images. The pelican eel also has a very long, whip-like tail. Specimens that have been brought to the surface in fishing nets have been known to have their long tails tied into several knots.

The pelican eel uses a whip-like tail for movement. The end of the tail bears a complex organ with numerous tentacles, which glows pink and gives off occasional bright-red flashes. The colors on its tail are displayed through its light-emitting photophores.[9] This is presumably a lure to attract prey, although its presence at the far end of the body from the mouth suggests the eel may have to adopt an unusual posture to use it effectively. Pelican eels are also unusual that the ampullae of the lateral line system projects from the body, rather than being contained in a narrow groove; this may increase its sensitivity.[10]

The pelican eel grows to about 0.75 m (2.5 ft) in length, though lengths of 1m are plausible.[11] Another interesting fact is that the pelican eel does not appear to display sexual dimorphism.[9] Pelican eels are black or olive and some subspecies may have a thin lateral white stripe.

Diet

The stomach can stretch and expand to accommodate large meals, although analysis of stomach contents suggests they primarily eat small crustaceans. Despite the great size of the jaws, which occupy about a quarter of the animal's total length, it has only tiny teeth, which would not be consistent with a regular diet of large fish.[10] The large mouth may be an adaptation to allow the eel to eat a wider variety of prey when food is scarce. It can also be used like a large net. The eel can swim into large groups of shrimp or other crustaceans with its mouth closed, opening wide as it closely approaches prey, scooping them up to be swallowed.[5] The pelican eel is also known to feed on cephalopods (squid) and other small invertebrates. When the eel gulps its prey into its massive jaws, it also takes in a large amount of water, which is then slowly expelled through its gill slits.[5] Pelican eels themselves are preyed upon by lancetfish and other deep sea predators. Recent studies have shown that pelican eels are active participants in their pursuit of food, rather than passively waiting for prey to fall into their large mouths.[12] The pelican eel is not known to undergo vertical diurnal migration like other eels.[13]

Reproduction and life cycle

Not much is known about the reproductive habits of the pelican eel. Similar to other eels, when pelican eels are first born, they start in the leptocephalus stage, meaning that they are extremely thin and transparent.[14] Until they reach their juvenile stage, they interestingly have very small body organs and do not contain any red blood cells. As they mature, the males undergo a change that causes enlargement of the olfactory organs, responsible for the sense of smell, and degeneration of the teeth and jaws. The females, on the other hand, remain relatively unchanged as they mature. The large olfactory organs in the males indicates that they may locate their mates through pheromones released by the females. Many researchers believe that the eels die shortly after reproduction.[15]

Distribution and habitat

The pelican eel has been found in the temperate and tropical areas of all oceans.[3] In the North Atlantic, it seems to have a range in depth from 500 to 3,000 m (1,600 to 9,800 ft).[3] One Canadian-arctic specimen was found in Davis Strait at a depth of 1,136–1,154 m (3,727–3,786 ft), and also across the coasts of Greenland.[5] More recently, pelican eels have been spotted off the coast of Portugal, as well as near Hawaiian islands.

Interactions with humans

Because of the extreme depths at which it lives, most of what is known about the pelican eel comes from specimens that are inadvertently caught in deep sea fishing nets.[15] Although once regarded as a purely deep-sea species, since 1970, hundreds of specimens have been caught by fishermen, mostly in the Atlantic Ocean.[3] In October 2018, the first direct observation of a gulper eel was made by a group of researchers about 1500 kilometers off the coast of Portugal near the islands called the Azores. The team witnessed the aggressive nature of the eel's hunting process, as it was constantly moving around in the water column to attempt to find prey.[12] In September 2018, the E/V Nautilus team also witnessed a juvenile gulper eel inflating its mouth in attempt to catch prey in the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (PMNM).[16] Until these recent explorations, not much has been analyzed by researchers of the behavior of gulper eels.

Phylogenetic relationship to other species

In 2003, researchers from the University of Tokyo sequenced mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from specimens of Eurypharynx pelicanoides and Saccopharynx lavenbergi. After comparing the sequences from the specimens with other known sequences, they found that Eurypharynx pelicanoides and Saccopharynx lavenbergi were closely related and genetically distinct from anguilliformes.[17]

See also

References

- https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/18227119/45085416

- Poulsen, Jan Y.; Miller, Michael J.; Sado, Tetsuya; Hanel, Reinhold; Tsukamoto, Katsumi; Miya, Masaki; Fugmann, Sebastian D. (25 July 2018). "Resolving deep-sea pelagic saccopharyngiform eel mysteries: Identification of Neocyema and Monognathidae leptocephali and establishment of a new fish family "Neocyematidae" based on larvae, adults and mitogenomic gene orders". PLOS ONE. 13 (7): e0199982. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1399982P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0199982. PMC 6059418. PMID 30044814.

- Nielsen, Jørgen G.; E. Bertelsen; Åse Jespersen (September 1989). "The Biology of Eurypharynx pelecanoides (Pisces, Eurypharyngidae)". Acta Zoologica. 70 (3): 187–197. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6395.1989.tb01069.x.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2015). "Eurypharynx pelecanoides" in FishBase. February 2015 version.

- Coad, Brian W. (2018). "Family 15. Eurypharyngidae: Gulpers, Grandgousiers (1)". Marine Fishes of Arctic Canada. By Møller, Peter Rask; Renaud, Claude B.; Alfonso, Noel; et al. Coad, Brian W.; Reist, James D. (eds.). University of Toronto Press. pp. 217–218. doi:10.3138/j.ctt1x76h0b.38 (inactive 17 January 2021). ISBN 978-1-4426-4710-7. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt1x76h0b.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- Paxton, John R.; Eschmeyer, William N. (1998). Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. p. 90. ISBN 0-12-547665-5.

- Gulper Eel – Pelican Eel, Frightening Deep Sea Jaws | Animal Pictures and Facts. FactZoo.com. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- Ozaka, Chieko; Yamamoto, Naoyuki; Nielsen, Jørgen G.; Somiya, Hiroaki (1 November 2011). "The aglomerular kidney of the deep-sea gulper eel Saccopharynx ampullaceus (Saccopharyngiformes: Saccopharyngidae)". Ichthyological Research. 58 (4): 297–301. doi:10.1007/s10228-011-0227-1. ISSN 1616-3915. S2CID 24744228.

- "Gulper Eel". Our Breathing Planet. 6 December 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- McCosker, John E. (1998). Paxton, J.R.; Eschmeyer, W.N. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-12-547665-2.

- Bray, Dianne J. (2011), "Gulper Eel, Eurypharynx pelecanoides".. Fishes of Australia, accessed 7 October 2014

- SchembriOct. 4, Frankie; 2018; Am, 8:00 (4 October 2018). "First direct observation of hunting pelican eel reveals a bizarre fish with an inflatable head". Science | AAAS. Retrieved 10 February 2020.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- DeVaney, Shannon C. (1 October 2016). "Species Distribution Modeling of Deep Pelagic Eels". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 56 (4): 524–530. doi:10.1093/icb/icw032. ISSN 1540-7063. PMID 27252208.

- "Reproduction". bioweb.uwlax.edu. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- Gulper Eel – Deep Sea Creatures on Sea and Sky. Seasky.org. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- "Watch a Gulper Eel Inflate and Deflate Itself, Shocking Scientists". Animals. 21 September 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- Inoue, J. G. (27 June 2003). "Evolution of the Deep-Sea Gulper Eel Mitochondrial Genomes: Large-Scale Gene Rearrangements Originated Within the Eels". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 20 (11): 1917–1924. doi:10.1093/molbev/msg206. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 12949142.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eurypharynx pelecanoides. |

- "Eurypharynx pelecanoides". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 24 January 2006.

- "Gulper Eel – Pelican Eel, Frightening Deep Sea Jaws." Factzoo.com. CopyLeft, 2010. Web. 2 May 2015.

- "Gulper Eel." – Deep Sea Creatures on Sea and Sky. See and Sky, 1998. Web. 2 May 2015.

External links

- EVNautilus. "Gulper Eel Balloons Its Massive Jaws". YouTube.