People's Liberation Army Rocket Force

The People's Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF; Chinese: 中国人民解放军火箭军), formerly the Second Artillery Corps (SAC; Chinese: 第二炮兵), is the strategic and tactical missile forces of the People's Republic of China. The PLARF is a component part of the People's Liberation Army and controls the nation's arsenal of land-based ballistic missiles—both nuclear and conventional. The armed service branch was established on 1 July 1966 and made its first public appearance on 1 October 1984. The headquarters for operations is located at Qinghe, Beijing. The PLARF is under the direct command of the Chinese Central Military Commission.

| People's Liberation Army Rocket Force | |

|---|---|

| 中国人民解放军火箭军 | |

Emblem of the People's Liberation Army Rocket Force | |

| Active | 1966–2015 (Second Artillery Corps) 2016–present (Rocket Force) |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Type | Tactical and strategic missile force |

| Role | Strategic deterrence, second strike |

| Size | 100,000 personnel |

| Part of | |

| Headquarters | Qinghe, Haidian District, Beijing, China |

| Colors | Red, gold, dark green |

| March | "March of the Rocket Force" (《火箭军进行曲》) |

| Equipment | Ballistic missiles, cruise missiles |

| Engagements | Third Taiwan Strait Crisis |

| Commanders | |

| Commander | General Zhou Yaning |

| Political Commissar | General Wang Jiasheng |

| Insignia | |

| Flag |  |

| Badge |  |

In total, China is estimated to be in possession of 320 nuclear warheads as of 2020, with an unknown number of them active and ready to deploy.[2] In 2013, United States Intelligence estimated the Chinese active ICBM arsenal to range between 50 and 75 land and sea-based missiles,[3] but more recent intelligence assessments in 2019 put China's ICBM count at around 90 and growing rapidly.[4] The PLARF comprises approximately 100,000 personnel and six ballistic missile brigades. The six brigades are independently deployed in different military regions throughout the country.

The name was changed to the People's Liberation Army (PLA) Rocket Force on 1 January 2016.[5][6] Despite claims by some, there appears to be no evidence to suggest that the new generation of Chinese ballistic-missile submarines will come under PLARF control.[7][8] China has the largest land-based missile arsenal in the world. According to Pentagon estimates, this includes 1,200 conventionally armed short-range ballistic missiles, two hundred to three hundred conventional medium-range ballistic missiles and an unknown number of conventional intermediate-range ballistic missiles, as well as two to three hundred ground-launched cruise missiles. Many of these are extremely accurate, which would allow them to destroy targets even without nuclear warheads.[9]

History

In the late 1980s, China was the world's third-largest nuclear power, possessing a small but credible nuclear deterrent force of approximately 100 to 400 nuclear weapons. Beginning in the late 1970s, China deployed a full range of nuclear weapons and acquired a nuclear second-strike capability. The nuclear forces were operated by the 100,000-person Strategic Missile Force, which was controlled directly by the Joint staff.

China began developing nuclear weapons in the late 1950s with substantial Soviet assistance. With the Sino-Soviet split in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Soviet Union withheld plans and data for an atomic bomb, abrogated the agreement on transferring defense and nuclear technology, and began the withdrawal of Soviet advisers in 1960. Despite the termination of Soviet assistance, China committed itself to continue nuclear weapons development to break "the superpowers' monopoly on nuclear weapons," to ensure Chinese security against the Soviet and United States threats, and to increase Chinese prestige and power internationally.

China made fast progress in the 1960s in developing nuclear weapons. In a 32-month period, China successfully tested its first atomic bomb on October 16, 1964 at Lop Nor, launched its first nuclear missile on October 25, 1966 and detonated its first hydrogen bomb on June 14, 1967. Deployment of the Dongfeng-1 conventionally armed short-range ballistic missile and the Dongfeng-2 (CSS-1) medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) occurred in the 1960s. The Dongfeng-3 (CCS-2) intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) was successfully tested in 1969. Although the Cultural Revolution disrupted the strategic weapons program less than other scientific and educational sectors in China, there was a slowdown in succeeding years.

Gansu hosted a missile launching area.[10] China destroyed 9 U-2 surveillance craft while two went missing when they attempted to spy on it.[11]

In the 1970s the nuclear weapons program saw the development of MRBM, IRBM and ICBMs and marked the beginning of a deterrent force. China continued MRBM deployment, began deploying the Dongfeng-3 IRBM and successfully tested and commenced deployment of the Dongfeng-4 (CSS-4) limited-range ICBM.

By 1980 China had overcome the slowdown in nuclear development caused by the Cultural Revolution and had successes in its strategic weapons program. In 1980 China successfully test launched its full-range ICBM, the Dongfeng-5 (CCS-4); the missile flew from central China to the Western Pacific, where it was recovered by a naval task force. The Dongfeng-5 possessed the capability to hit targets in the western Soviet Union and the United States. In 1981 China launched three satellites into space orbit from a single launch vehicle, indicating that China might possess the technology to develop multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs). China also launched the Type 092 submarine SSBN (Xia-class) in 1981, and the next year it conducted its first successful test launch of the Julang-2 submarine-launched ballistic missile (CSS-NX-4). In addition to the development of a sea-based nuclear force, China began considering the development of tactical nuclear weapons. PLA exercises featured the simulated use of tactical nuclear weapons in offensive and defensive situations beginning in 1982. Reports of Chinese possession of tactical nuclear weapons had remained unconfirmed in 1987.

In 1986 China possessed a credible deterrent force with land, sea and air elements. Land-based forces included ICBMs, IRBMs, and MRBMs. The sea-based strategic force consisted of SSBNs. The Air Force's bombers were capable of delivering nuclear bombs but would be unlikely to penetrate the sophisticated air defenses of modern military powers.

China's nuclear forces, in combination with the PLA's conventional forces, served to deter both nuclear and conventional attacks on the Chinese lands. Chinese leaders pledged to not use nuclear weapons first (no first use), but pledged to absolutely counter-attack with nuclear weapons if nuclear weapons are used against China. China envisioned retaliation against strategic and tactical attacks and would probably strike countervalue rather than counterforce targets. The combination of China's few nuclear weapons and technological factors such as range, accuracy, and response time limited the effectiveness of nuclear strikes against counterforce targets. China has been seeking to increase the credibility of its nuclear retaliatory capability by dispersing and concealing its nuclear forces in difficult terrain, improving their mobility, and hardening its missile silos.

The CJ-10 long-range cruise missile made its first public appearance during the military parade on the 60th Anniversary of the People's Republic of China; the CJ-10 represents the next generation in rocket weapons technology in the PLA.

In late 2009, it was reported that the Corps was constructing a 3,000–5,000-kilometre (1,900–3,100 mi) long underground launch and storage facility for nuclear missiles in the Hebei province.[12] 47 News reported that the facility was likely located in the Taihang Mountains.[13]

On 9 January 2014, a Chinese hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV) referred to as the WU-14 was allegedly spotted flying at high speeds over the country. The flight was confirmed by the Pentagon as a hypersonic missile delivery vehicle capable of penetrating the U.S. missile defense system and delivering nuclear warheads. The WU-14 is reportedly designed to be launched as the final stage of a Chinese ICBM traveling at Mach 10, or 12,360 km/h (7,680 mph). Two Chinese technical papers from December 2012 and April 2013 show the country has concluded hypersonic weapons pose "a new aerospace threat" and that they are developing satellite directed precision guidance systems. China is the third country to enter the "hypersonic arms race" after Russia and the United States. Russia is jointly developing with India the Mach 6 (7,300 km/h (4,500 mph)) scramjet-powered Brahmos-II. The U.S. Air Force has flown the X-51A Waverider technology demonstrator and the U.S. Army has flight tested the Advanced Hypersonic Weapon.[14] China later confirmed the successful test flight of a "hypersonic missile delivery vehicle," but claimed it was part of a scientific experiment and not aimed at a target.[15]

US Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center estimated that by 2022 the number of Chinese nuclear warheads capable of reaching the United States could expand to well over 100.[16]

Missile ranges

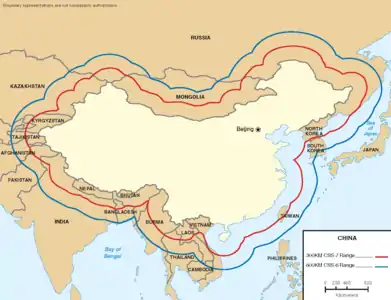

Maximum range for China's conventional SRBM force (2006)

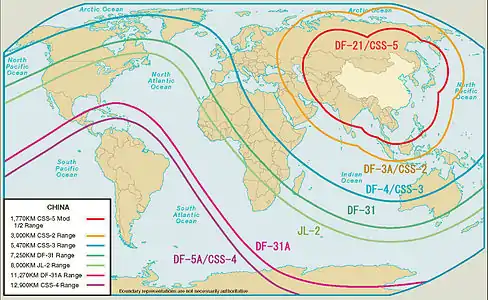

Maximum range for China's conventional SRBM force (2006) Medium and intercontinental ballistic missile ranges (2007)

Medium and intercontinental ballistic missile ranges (2007)

Active missiles

Hypersonic glide vehicles

Intercontinental ballistic missiles

Intermediate-range ballistic missiles

- DF-26 - 1000

Medium-range ballistic missiles

- DF-21D Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile - 50

- DF-21C - 100

- DF-21A - 200

- DF-17

- DF-16 - 50

Cruise missiles

- CJ-10A - 500

Obsolete missiles

Intermediate ballistic missiles

- DF-3A, CSS-2 - In service from 1971 to 2014

Order of battle

The PLARF is organised into Bases, sometimes called Armies, with each Base commanding a number of Brigades, and each Brigade commanding a number of Battalions. As a rule of thumb, each Base operates between 3 and 5 brigades, with a mix of conventional and nuclear-capable Brigades in each. The exception is Base 61, which is believed to have 7 Brigades, all of which are conventional. In addition, it is currently somewhat unclear as to whether the Chinese theater commands or the PLARF itself has operational control over the conventional ballistic missile units, though it seems likely that the PLARF acts in coordination with, but not taking orders from, the theater commands with regards to the use of conventional ballistic missiles, with control of nuclear weapons continuing to be exercised at the Central Military Commission level.[18] Furthermore, it appears that the number of missiles assigned to each Brigade differs by missile type, as well as the individual Brigade itself.

Base 61, Huangshan

| Brigade No | Location | Missile Type |

|---|---|---|

| 611 | Chizhou City, Anhui Province (Chinese: 安徽省池州市) | DF-21A |

| 612 | Jingdezhen City, Jiangxi Province (Chinese: 江西省景德镇市) | DF-21A |

| 613 | Shangrao City, Jiangxi Province (Chinese: 江西省上饶市) | DF-15B |

| 614 | Yong'an City,Fujian Province (Chinese: 福建省永安市) | DF-11A |

| 615 | Meizhou City, Guangdong Province (Chinese: 广东省梅州市) | DF-11A |

| 616 | Ganzhou City, Jiangxi Province (Chinese: 江西省赣州市) | DF-15 |

| 617 | Jinhua City, Zhejiang Province (Chinese: 浙江省金华市) | DF-16 |

Base 62, Kunming

- 621 Brigade, Yibin, (DF-21C)

- 622 Brigade, Yuxi, (DF-31A)

- 623 Brigade, Liuzhou, (CJ-10A)

- 624 Brigade, Danzhou, (DF-21D)

- 625 Brigade, Jianshui, (DF-26)

- 626 Brigade, Qingyuan, (DF-26)

- 627 Brigade, Jieyang, (DF-17)

Base 63, Huaihua

- 631 Brigade, Jingzhou, (DF-5B)

- 632 Brigade, Shaoyang, (DF-31)

- 633 Brigade, Huitong, (DF-5A)

- 634 Brigade, Tongdao, missile type unknown.

- 635 Brigade, Yichun, (CJ-10)

- 636 Brigade, Shaoguan, (DF-16)

- 637 Brigade, location and missile type unknown

Base 64, Lanzhou

- 641 Brigade, Hancheng, (DF-31)

- 642 Brigade, Datong, (DF-31A)

- 643 Brigade, Tianshui, (DF-31AG)

- 644 Brigade, Hanzhong, missile type unknown

- 645 Brigade, Yinchuan, missile type unknown

- 646 Brigade, Korla, (either DF-21B or 21C)

Base 65, Shenyang

- 651 Brigade, Dalian, (DF-21, sub-type unknown)

- 652 Brigade, Tonghua, (DF-21C or DF-21D)

- 653 Brigade, Laiwu, (DF-21D)

- 654 Brigade, Dalian, (DF-26)

Base 66, Luoyang

- 661 Brigade, Lingbao, (DF-5B)

- 662 Brigade, Luanchuan, (DF-4)

- 663 Brigade, Nanyang, (DF-31A)

- 664 Brigade, Luoyang, (DF-31AG)

- 665 Brigade, location and missile type unknown

- 666 Brigade, Xinyang, (DF-26)

In addition, the PLARF operates another Base, Base 67,[21] which is responsible for nuclear warhead storage, warhead transport, warhead inspection and nuclear weapon's training. In addition, it is believed to form part of the nuclear C3 [Command, Control and Communications] network, though it is unknown if this network is PLARF-only, shared between the PLARF and military commands, or if it used by the Central Military Commission, which is believed to have its own communication system for the nuclear forces. The main nuclear storage facility is reportedly located in Taibai County, where large-scale tunneling activities have taken place. The main storage depot is apparently under Mount Taibai itself, with related Base 67 facilities spread throughout the rest of the county. Additionally, it appears that each missile Base also has a smaller storage facility and depot. It is likely that warheads that require maintenance or testing, as well as a centralised reserve stock, are held at the Mount Taibai facility, with relatively few warheads distributed to the Bases and Brigades. It is likely that missile Bases would receive additional warheads from the central depot in times of high tension. It seems that the structure of a main unit in Taibai County, with smaller replica units throughout the Bases, is repeated in the transportation units. Warhead and missile transport in China is heavily reliant on the rail and road systems, likely why a large-scale rail project was constructed in the 1960s by the PLA in the area of Baoji, a large city in Shaanxi province and the location of Base 67's headquarters since that same time period. This became a concern after the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, where the vulnerability of transport networks in Shaanxi province was dramatically proven. While it is difficult to gain an accurate OOB for Base 67, with open-source documentation dating back to before the 2015 reforms, some details are known and have been reproduced below:[22]

Base 67, Baoji

- Equipment Inspection Institute, called Unit 96411 pre-reform

- Unknown unit, known as Unit 96412

- Technology Service Regiment, called Unit 96421 pre-reform

- Transportation Regiment, called Unit 96422 pre-reform

- Training Regiment, called Unit 96423 pre-reform

- Maintenance Regiment, called Unit 96424 pre-reform

- Communications Regiment, called Unit 96425 pre-reform

Command, Control, and Communications

The PLARF has operated a separate command and control structure from the rest of the PLA since 1967.[23] The goal of the system is to ensure tight control of nuclear warheads at the highest levels of government. This is done by the Central Military Commission having direct control of the PLARF, outside of the structure of military regions. For nuclear weapons, the command structure is believed to run from the CMC, to the headquarters of the PLARF in Beijing, from there to each Artillery Base, and from each Artillery Base down to the individual Brigade. From there, the Brigade transmits firing orders to the launch companies under its control. In the case of conventional ballistic missiles, it is reasonable to assume that more autonomy will be provided in wartime, with command likely being issued from the Bases, which are believed to coordinate with their respective Military Regions on targeting and conventional missile use.

Chinese nuclear C3 capabilities are centered around fibre-optic and satellite-based communication networks, replacing older radio command networks that made up the-then Second Artillery's C3 infrastructure before the 1990s. While historically Chinese nuclear missile forces had to launch from pre-prepared sites, the newest generation of nuclear-capable missiles (the DF-26 and DF-31AG) have been seen deploying to, and launching from, unprepared sites in exercises. This would corroborate reports that PLARF communications regiments are being trained in the ability to set up telephone and command networks "on-the-fly". The reason for these changes likely has to do with concerns about PLARF survivability; China's commitment to a no-first-use policy means that its nuclear forces have to be capable of both surviving a first-strike, and receiving the orders required to fire back.

Transporter Erector Launchers

- TA580/TAS5380

- TA5450/TAS5450

- HTF5680A1

- WS2300

- WS2400

- WS2500

- WS2600

- WS21200 (used exclusively by Pakistan)

- WS51200 (used exclusively by North Korea)

Tractor Trucks

Operations in Saudi Arabia

The PLARF Golden Wheel Project (金轮工程) co-operates the DF-3 and DF-21 medium-range ballistic missiles in Saudi Arabia since the establishment of Royal Saudi Strategic Missile Force in 1984.

See also

- Dongfeng (missile)

- Nuclear triad

- List of states with nuclear weapons

- Qian Xuesen (also known as Tsien Hsue-shen)

References

Citations

- "The PLA Oath" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-05-09. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

I am a member of the People's Liberation Army. I promise that I will follow the leadership of the Communist Party of China...

- "Nuclear weapon modernization continues but the outlook for arms control is bleak". sipri.org. 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- 2013 China report Archived 2015-01-13 at the Wayback Machine, defense.gov

- Archived 2020-08-17 at the Wayback Machine, defense.gov

- "China's nuclear policy, strategy consistent: spokesperson". Xinhua. Beijing: People's Republic of China. 1 January 2016. Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- Fisher, Richard D., Jr. (6 January 2016). "China establishes new Rocket Force, Strategic Support Force". Jane's Defence Weekly. Surrey, UK: Jane's Information Group. 53 (9). ISSN 0265-3818.

This report also quotes Chinese expert Song Zhongping saying that the Rocket Force could incorporate 'PLA sea-based missile unit[s] and air-based missile unit[s]'.

- Medcalf, Rory (2020). The Future of the Undersea Deterrent: A Global Survey. Acton, Australia: National Security College, The [[[Australian National University]]. pp. 26–27. ISBN 9781925084146. Archived from the original on 2020-04-13. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- Logan, David C; Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs (Institute for National Strategic Studies at National Defense University) (2016). "China's Future SSBN Command and Control Structure". Strategic Forum. Washington, D.C.: NDU Press (299): 2–3. OCLC 969995006.

- Keck, Zachary (29 July 2017). "Missile Strikes on U.S. Bases in Asia: Is This China's Real Threat to America?". The National Interest. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- Ben R. Rich; Leo Janos (26 February 2013). Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My Years of Lockheed. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-24693-4. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Robin D. S. Higham (2003). One Hundred Years of Air Power and Aviation. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 228–. ISBN 978-1-58544-241-6. Archived from the original on 2020-02-14. Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- "China Builds Underground 'Great Wall' Against Nuke Attack". The Chosun Ilbo. December 14, 2009. Archived from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- Zhang, Hui (31 January 2012). "China's Underground Great Wall: Subterranean Ballistic Missiles". Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Harvard University. Archived from the original on 29 June 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- China has successfully tested its first hypersonic missile Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine - Army Recognition, 14 January 2014

- Waldron, Greg (16 January 2014). "China confirms test of "hypersonic missile delivery vehicle"". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on 29 June 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- Defense Intelligence Ballistic Missile Analysis Committee (June 2017). Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat (Report). NASIC. Archived from the original on 2019-06-18. Retrieved 2019-06-29.

- "Pentagon Report And Chinese Nuclear Forces". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 2016-05-19. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Logan, David. "PLA Reforms and China's Nuclear Forces" (PDF). Joint Forces Quarterly. 83: 57–62. Archived from the original on 2020-01-12. Retrieved 2020-01-12.

- Saunders, Phillip (2019). Chairman Xi Remakes the PLA: Assessing Chinese Military Reforms. National Defence University Press. pp. 401–405.

- China TV, CCTV (29 Dec 2020). Missing or empty

|title=(help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Gill, Bates; Ni, Adam (2019-03-04). "The People's Liberation Army Rocket Force: reshaping China's approach to strategic deterrence" (PDF). Australian Journal of International Affairs. 73 (2): 160–180. doi:10.1080/10357718.2018.1545831. ISSN 1035-7718. S2CID 159087704.

- Stokes, Mark (March 12, 2010). "China's Nuclear Warhead Storage and Handling System" (PDF). Project 2049 Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 12, 2020.

- "NUCLEAR COMMAND, CONTROL, AND COMMUNICATIONS SYSTEMS OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA". Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability. 2019-07-18. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

Sources

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies document: "China".

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies document: "China".

Further reading

- Federation of American Scientists et al. (2006): Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning

- China Nuclear Forces Guide Federation of American Scientists

- Enrico Fels (February 2008): Will the Eagle strangle the Dragon? An Assessment of the U.S. Challenges towards China's Nuclear Deterrence, Trends East Asia Analysis No. 20.

External links

- Strategic Missile Force SinoDefence.com (WaybackMachine Dec. 2013)

- PLA Second Artillery Corps SinoDefence.com (Dec. 2010)

- Second Artillery Corps FAS.org

- Second Artillery Corps (SAC) NTI.org (WaybackMachine Dec. 2011)