China and weapons of mass destruction

The People's Republic of China has developed and possesses weapons of mass destruction, including chemical and nuclear weapons. The first of China's nuclear weapons tests took place in 1964, and its first hydrogen bomb test occurred in 1967. Tests continued until 1996, when China signed the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). China has acceded to the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BWC) in 1984 and ratified the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) in 1997.

| People's Republic of China | |

|---|---|

| |

| First nuclear weapon test | October 16, 1964 |

| First thermonuclear weapon test | June 17, 1967 |

| Last nuclear test | July 29, 1996 |

| Largest yield test | 4 Mt

|

| Total tests | 45[1] |

| Current stockpile | ~350[2] (2020 est) |

| Current strategic arsenal | Unknown |

| Cumulative strategic arsenal in megatonnage | 294 megatons (2009 est.)[3][4] |

| Maximum missile range | 15,000 km[5] |

| NPT party | Yes (1992, one of five recognized powers) |

| Weapons of mass destruction |

|---|

|

| By type |

| By country |

|

| Proliferation |

| Treaties |

|

The number of nuclear warheads in China's arsenal is a state secret. There are varying estimates of the size of China's arsenal. China was estimated by the Federation of American Scientists to have an arsenal of about 260 total warheads as of 2015, which made it the second smallest nuclear arsenal amongst the five nuclear weapon states acknowledged by the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, and one of 320 total warheads by the SIPRI Yearbook 2020, the third highest.[6] According to some estimates, the country could "more than double" the "number of warheads on missiles that could threaten the United States by the mid-2020s".[7]

Early in 2011, China published a defense white paper, which repeated its nuclear policies of maintaining a minimum deterrent with a no-first-use pledge. Yet China has yet to define what it means by a "minimum deterrent posture". This, together with the fact that "it is deploying four new nuclear-capable ballistic missiles, invites concern as to the scale and intention of China’s nuclear upgrade".[7]

Chemical weapons

The Republic of China signed the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) on January 13, 1993. The People’s Republic of China ratified the CWC on April 25, 1997.[8]

China was found to have supplied Albania with a small stockpile of chemical weapons in the 1970s during the Cold War.[9]

Biological weapons

China is currently a signatory of the Biological Weapons Convention and Chinese officials have stated that China has never engaged in biological activities with offensive military applications. However, China was reported to have had an active biological weapons program in the 1980s.[10]

Kanatjan Alibekov, former director of one of the Soviet germ-warfare programs, said that China suffered a serious accident at one of its biological weapons plants in the late 1980s. Alibekov asserted that Soviet reconnaissance satellites identified a biological weapons laboratory and plant near a site for testing nuclear warheads. The Soviets suspected that two separate epidemics of hemorrhagic fever that swept the region in the late 1980s were caused by an accident in a lab where Chinese scientists were weaponizing viral diseases.[11]

US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright expressed her concerns over possible Chinese biological weapon transfers to Iran and other nations in a letter to Senator Bob Bennett (R-Utah) in January 1997.[12] Albright stated that she had received reports regarding transfers of dual-use items from Chinese entities to the Iranian government which concerned her and that the United States had to encourage China to adopt comprehensive export controls to prevent assistance to Iran's alleged biological weapons program. The United States acted upon the allegations on January 16, 2002, when it imposed sanctions on three Chinese firms accused of supplying Iran with materials used in the manufacture of chemical and biological weapons. In response to this, China issued export control protocols on dual use biological technology in late 2002.[13]

Nuclear weapons

History

Mao Zedong decided to begin a Chinese nuclear-weapons program during the First Taiwan Strait Crisis of 1954–1955 over the Quemoy and Matsu Islands. While he did not expect to be able to match the large American nuclear arsenal, Mao believed that even a few bombs would increase China's diplomatic credibility. Construction of uranium-enrichment plants in Baotou and Lanzhou began in 1958, and a plutonium facility in Jiuquan and the Lop Nur nuclear test site by 1960. The Soviet Union provided assistance in the early Chinese program by sending advisers to help in the facilities devoted to fissile material production[14] and, in October 1957, agreed to provide a prototype bomb, missiles, and related technology. The Chinese, who preferred to import technology and components to developing them within China, exported uranium to the Soviet Union, and the Soviets sent two R-2 missiles in 1958.[15]

That year, however, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev told Mao that he planned to discuss arms control with the United States and Britain. China was already opposed to Khrushchev's post-Stalin policy of "peaceful coexistence". Although Soviet officials assured China that it was under the Soviet nuclear umbrella, the disagreements widened the emerging Sino-Soviet split. In June 1959, the two nations formally ended their agreement on military and technology cooperation,[15] and in July 1960, all Soviet assistance with the Chinese nuclear program was abruptly terminated and all Soviet technicians were withdrawn from the program.[16]

According to Arms Control and Disarmament Agency director William Foster, the American government, under Kennedy and Johnson administration, was concerned about the program and studied ways to sabotage or attack it, perhaps with the aid of Taiwan or the Soviet Union, but Khrushchev was not interested. The Chinese conducted their first nuclear test, code-named 596, on 16 October 1964,[14] and acknowledged that their program would have been impossible to complete without the Soviet help.[15] China's last nuclear test was on July 29, 1996.[17] According to the Australian Geological Survey Organisation in Canberra, the yield of the 1996 test was 1–5 kilotons. This was China's 22nd underground test and 45th test overall.

Size

China has made significant improvements in its miniaturization techniques since the 1980s. There have been accusations, notably by the Cox Commission, that this was done primarily by covertly acquiring the U.S.'s W88 nuclear warhead design as well as guided ballistic missile technology.[18][19][20] Chinese scientists have stated that they have made advances in these areas, but insist that these advances were made without espionage.

The international community has debated the size of the Chinese nuclear force since the nation first acquired such technology. Because of strict secrecy it is very difficult to determine the exact size and composition of China's nuclear forces. Estimates vary over time. Several declassified U.S. government reports give historical estimates. The 1984 Defense Intelligence Agency's Defense Estimative Brief estimates the Chinese nuclear stockpile as consisting of between 150 and 160 warheads.[21] A 1993 United States National Security Council report estimated that China's nuclear deterrent force relied on 60 to 70 nuclear armed ballistic missiles.[22] The Defense Intelligence Agency's The Decades Ahead: 1999 – 2020 report estimates the 1999 Nuclear Weapons' Inventory as between 140 and 157.[23] In 2004 the U.S. Department of Defense assessed that China had about 20 intercontinental ballistic missiles capable of targeting the United States.[24] In 2006 a U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency estimate presented to the Senate Armed Services Committee was that "China currently has more than 100 nuclear warheads."[25]

A variety of estimates abound regarding China's current stockpile. Although the total number of nuclear weapons in the Chinese arsenal is unknown, as of 2005 estimates vary from as low as 80 to as high as 2,000. The 2,000-warhead estimate has largely been rejected by diplomats in the field. It appears to have been derived from a 1990s-era Usenet post, in which a Singaporean college student made unsubstantiated statements concerning a supposed 2,000-warhead stockpile.[26][27]

In 2004, China stated that "among the nuclear-weapon states, China ... possesses the smallest nuclear arsenal," implying China has fewer than the United Kingdom's 200 nuclear weapons.[28] Several non-official sources estimate that China has around 400 nuclear warheads. However, U.S. intelligence estimates suggest a much smaller nuclear force than many non-governmental organizations.[29]

In 2011, high estimates of the Chinese nuclear arsenal again emerged. One three-year study by Georgetown University raised the possibility that China had 3,000 nuclear weapons, hidden in a sophisticated tunnel network.[30] The study was based on state media footage showing tunnel entrances, and estimated a 4,800 km (3,000 mile) network. The tunnel network was revealed after the 2008 Sichuan earthquake collapsed tunnels in the hills. China has confirmed the existence of the tunnel network.[31] In response, the US military was ordered by law to study the possibility of this tunnel network concealing a nuclear arsenal.[32] However, the tunnel theory has come under substantial attack due to several apparent flaws in its reasoning. From a production standpoint, China probably does not have enough fissile material to produce 3,000 nuclear weapons. Such an arsenal would require 9–12 tons of plutonium as well as 45–75 tons of enriched uranium and a substantial amount of tritium.[33][34] The Chinese are estimated to have only 2 tons of weapons-grade plutonium, which limits their arsenal to 450–600 weapons, despite a 18-ton disposable supply of uranium, theoretically enough for 1,000 warheads.[33]

As of 2011, the Chinese nuclear arsenal was estimated to contain 55–65 ICBMs.[35]

In 2012, STRATCOM commander C. Robert Kehler said that the best estimates were "in the range of several hundred" warheads and FAS estimated the current total to be "approximately 240 warheads".[36]

The U.S. Department of Defense 2013 report to Congress on China's military developments stated that the Chinese nuclear arsenal consists of 50–75 ICBMs, located in both land-based silos and Ballistic missile submarine platforms. In addition to the ICBMs, the report stated that China has approximately 1,100 short-range ballistic missiles, although it does not have the warhead capacity to equip them all with nuclear weapons.[37]

Nuclear policy

China is one of the five nuclear weapons states (NWS) recognized by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, which China ratified in 1992. China is the only NWS[38] to give an unqualified security assurance to non-nuclear-weapon states:

- "China undertakes not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapon States or nuclear-weapon-free zones at any time or under any circumstances."[39]

Chinese public policy has always been one of the "no first use rule" while maintaining a deterrent retaliatory force targeted for countervalue targets.[1]

In 2005, the Chinese Foreign Ministry released a white paper stating that the government "would not be the first to use [nuclear] weapons at any time and in any circumstance". In addition, the paper went on to state that this "no first use" policy would remain unchanged in the future and that China would not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against any non-nuclear-weapon states or nuclear-weapon-free zones.[40]

China normally stores nuclear warheads separately from their launching systems, unless there is a heightened threat level.[41]

China, along with all other nuclear weapon states and all members of NATO with the exception of the Netherlands, decided not to sign the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, a binding agreement for negotiations for the total elimination of nuclear weapons.[42]

China refused to join talks in 2020 between the U.S. and Russia on extending their bilateral New START nuclear arms reduction treaty, as the Trump administration requested. China's position is that as its nuclear warhead arsenal is a small fraction of the U.S. and Russia arsenals, their inclusion in an arms reduction treaty is unnecessary.[43][44]

Nuclear proliferation

Historically, China has been implicated in the development of the Pakistani nuclear program before China ratified the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1992. In the early 1980s, China is believed to have given Pakistan a "package" including uranium enrichment technology, high-enriched uranium, and the design for a compact nuclear weapon.[45] China also received stolen technology that Abdul Qadeer Khan brought back to Pakistan and Pakistan set up a centrifuge plant in China as revealed in his letters which state "(1)You know we had cooperation with China for 15 years. We put up a centrifuge plant at Hanzhong (250km south-west of Xi'an). We sent 135 C-130 plane loads of machines, inverters, valves, flow meters, pressure gauges. Our teams stayed there for weeks to help and their teams stayed here for weeks at a time. Late minister Liu We, V. M. [vice minister] Li Chew, Vice Minister Jiang Shengjie used to visit us. (2)The Chinese gave us drawings of the nuclear weapon, gave us kg50 enriched uranium, gave us 10 tons of UF6 (natural) and 5 tons of UF6 (3%). Chinese helped PAEC [Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission, the rival organisation to the Khan Research Laboratories] in setting up UF6 plant, production reactor for plutonium and reprocessing plant."[46]

Amitai Etzioni of the Institute for Communitarian Policy Studies has suggested that the prevention of nuclear proliferation could be a fruitful area of cooperation between China and the United States, by which each country could "trust but verify" the other's intentions and "help them move away from the current distrust both sides exhibit in their dealings with each other."[47]

2010 IISS Military Balance

The following are estimates of China's strategic missile forces from the International Institute of Strategic Studies Military Balance 2010.[48] According to these estimates, China has up to 90 inter-continental range ballistic missiles (66 land-based ICBMs and 24 submarine-based JL-2 SLBMs), not counting MIRV warheads.

| Type | Missiles | Estimated Range |

|---|---|---|

| Inter-Continental Ballistic Missiles | ||

| DF-41 (CSS-X-10) ICBM | - | 14,000~15,000 km |

| DF-5A (CSS-4 Mod 2) ICBM | 20 | 13,000+ km |

| DF-31A (CSS-10 Mod 2) road-mobile ICBM | 24 | 11,200+ km |

| DF-31 (CSS-10) road-mobile ICBM | 12 | 7,200+ km |

| DF-4 (CSS-3) ICBM | 10 | 5,500 km |

| Intermediate Range Ballistic Missiles | ||

| DF-3A (CSS-2 Mod) IRBM | 2 | 3,000+ km |

| Medium Range Ballistic Missiles | ||

| DF-21C (CSS-5 Mod 3) road-mobile MRBM | 36 | 1,750+ km |

| DF-21 (CSS-5) road-mobile MRBM | 80 | 1,750+ km |

| Short Range Ballistic Missiles | ||

| DF-15 (CSS-6) road-mobile SRBM | 96 | 600 km |

| DF-11A (CSS-7 Mod 2) road-mobile SRBM | 108 | 300 km |

| Land Attack Cruise Missiles | ||

| DH-10 LACM | 54 | 3,000+ km |

| Submarine Launched Ballistic Missiles | ||

| JL-1 SLBM | 12 | 1,770+ km |

| JL-2 SLBM | 24 | 7,200+ km |

| Total | 478 | |

2010 DoD annual PRC military report

The following are estimates from the United States Department of Defense 2010 report to Congress concerning the Military Power of the People's Republic of China[49]

| Type | Launchers | Missiles | Estimated Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSS-2 IRBM | 5–10 | 15–20 | 3,000+ km |

| CSS-3 ICBM | 10–15 | 15–20 | 5,400+ km |

| DF-5 (CSS-4) ICBM | 20 | 20 | 13,000+ km |

| DF-31 ICBM | <10 | <10 | 7,200+ km |

| DF-31A ICBM | 10-15 | 10-15 | 11,200+ km |

| CSS-5 MRBM Mod 1/2 | 75-85 | 85-95 | 1,750+ km |

| CSS-6 SRBM | 90-110 | 350-400 | 600 km |

| CSS-7 SRBM | 120-140 | 700-750 | 300 km |

| DH-10 LACM | 45-55 | 200-500 | 1,500+ km |

| JL-1 SLBM | ? | ? | 1,770+ km |

| JL-2 SLBM | ? | ? | 7,200+ km |

| Total | 375–459 | 1,395–1,829 |

2006 FAS & NRDC report

The following table is an overview of PRC nuclear forces taken from a November 2006 report by Hans M. Kristensen, Robert S. Norris, and Matthew G. McKinzie of the Federation of American Scientists and the Natural Resources Defense Council titled Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning.[50]:202

| Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2006 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China designation | U.S./NATO designation | Year deployed | Range | Warhead x yield | Number deployed | Warheads deployed |

| Land-based missiles | ||||||

| DF-3A | CSS-2 | 1971 | 3,100 km | 1 x 3.3 Mt | 16 | 16 |

| DF-4 | CSS-3 | 1980 | 5500 km | 1 x 3.3 Mt | 22 | 22 |

| DF-5A | CSS-4 Mod 2 | 1981 | 13,000 km | 1 x 4–5 Mt | 20 | 20 |

| DF-21A | CSS-5 Mod 1/2 | 1991 | 2,150 km | 1 x 200–300 kt | 35 | 35 |

| DF-31 | (CSS-X-10) | 2006? | 7,250+ km | 1 x ? | n.a. | n.a. |

| DF-31A | n.a. | 2007–2009 | 11,270+ km | 1 x ? | n.a. | n.a. |

| Subtotal | 93 | 93 | ||||

| Submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs)** | ||||||

| JL-1 | CSS-NX-3 | 1986 | 1,770+ km | 1 x 200–300 kt | 12 | 12 |

| JL-2 | CSS-NX-4 | 2008–2010 ? | 8,000+ km | 1 x ? | n.a. | n.a. |

| Subtotal | 12 | 12 | ||||

| Total strategic ballistic missiles | 105 | 105 | ||||

| Aircraft*** | ||||||

| Hong-6 | B-6 | 1965 | 3,100 km | 1–3 x bomb | 100 | 20 |

| Attack | (Q-5, others?) | 1 x bomb | 20 | |||

| Subtotal | 40 | |||||

| Short-range tactical weapons | ||||||

| DF-15 | CSS-6 | 1990 | 600 km | 1 x low | ~300 | ? |

| DH-10? | (LACM) | 2006–2007 ? | ~1,500 km ? | 1 x low ? | n.a. | n.a. |

| Total | ~145 | |||||

Situation in 2013–14

After increasing during the Bush administration, the number of Chinese nuclear armed missiles capable of reaching North America leveled off during the Obama administration with delays in bringing forth new capabilities such as MIRV and operational sub launched missiles.[51] The U.S. DOD 2013 report to Congress continued to state that China had 50–75 ICBMs.[37] However the United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission stated that it was possible for China to finally have an operational Submarine-launched ballistic missile capability by the end of the year.[52] The US–China Economic and Security Review Commission stated in November 2014 that patrols with nuclear-armed submarines would take place before the end of the year, "giving China its first credible sea-based nuclear deterrent".[53]

Land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles

| Nuclear weapons |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Nuclear-armed states |

|

The Dongfeng 5A is a single-warhead, three-stage, liquid-fueled missile with a range of 13,000+ km. In 2000, General Eugene Habiger of the U.S. Air Force, then-commander of the U.S. Strategic Command, testified before Congress that China has 18 silo-based DF-5s.[54] Since the early 21st century, the Second Artillery Corps have also deployed up to 10 Solid-fueled mobile DF-31 ICBMs, with a range of 7,200+ km and possibly up to 3 MIRVs.[55] China has also developed the DF-31A, an intercontinental ballistic missile with a range of 11,200+ km with possibly 3–6 multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV) capability.

China stores many of its missiles in huge tunnel complexes; US Representative Michael Turner[56] referring to 2009 Chinese media reports said "This network of tunnels could be in excess of 5,000 kilometers (3,110 miles), and is used to transport nuclear weapons and forces,"[57] the Chinese Army newsletter calls this tunnel system an underground Great Wall of China.[58]

Medium-range ballistic missiles

Approximately 55% of China's missiles are in the medium-range category, targeted at regional theater targets.[50]:61

DF-3A/CSS-2

DF-21/CSS-5

Tactical cruise missiles

The CJ-10 long-range cruise missile made its first public appearance in 2009 during a military parade on the 60th Anniversary of the People's Republic of China as a part of the Second Artillery Corps' long-range conventional missile forces; the CJ-10 represents the next generation in rocket weapons technology in the People's Liberation Army (PLA). A similar naval cruise missile, the YJ-62, was also revealed during the parade; the YJ-62 serves as the PLA Navy's latest development into naval rocketry.

Long-range ballistic missiles

The Chinese categorize long-range ballistic missiles as ones with a range between 3000 and 8000 km.[50]:103

DF-4/CSS-3

The Dong Feng 4 or DF-4 (also known as the CSS-3) is a long-range two-stage Chinese intermediate-range ballistic missile with liquid fuel (nitric acid/UDMH). It was thought to be deployed in limited numbers in underground silos beginning in 1980.[50]:67 The DF-4 has a takeoff thrust of 1,224.00 kN, a takeoff weight of 82,000 kg, a diameter of 2.25 m, a length of 28.05 m, and a fin span of 2.74 m. It is equipped with a 2,190 kg nuclear warhead with 3,300 kt explosive yield, and its range is 5,500 km.[50]:68 The missile uses inertial guidance, resulting in a relatively poor CEP of 1,500 meters.

DF-5A/CSS-4 Mod 2

The Dongfeng 5 or DF-5 is a 3-stage Chinese ICBM. It has a length 32.6 m and a diameter of 3.35 m. It weighs 183 tonnes and has an estimated range of 12,000–15,000 kilometers.[50]:71–72 The DF-5 had its first flight in 1971 and was in operational service 10 years later. One of the downsides of the missile was that it took between 30 and 60 minutes to fuel.

DF-31/CSS-10

The Dong Feng 31 (or CSS-10) is a medium-range, three stage, solid propellant intercontinental ballistic missile developed by the People's Republic of China. It is a land-based variant of the submarine-launched JL-2.

DF-41/CSS-X-10 Nicknamed "Dongfeng-41"

The DF-41 (or CSS-X-10) is an intercontinental ballistic missile believed to be under development by China. It may be designed to carry Multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRV), delivering multiple nuclear warheads.

Nuclear cruise missiles

The US DoD estimated in 2006 that the PRC was developing ground- and air-launched cruise missiles that could easily be converted to carry nuclear warheads once developed.[59]

DH-10

The DongHai 10 (DH-10) is a cruise missile developed in the People's Republic of China. According to Jane's Defence Weekly, the DH-10 is a second-generation land-attack cruise missile (LACM), with over 4,000 km range, integrated inertial navigation system, GPS, terrain contour mapping system, and digital scene-matching terminal-homing system. The missile is estimated to have a circular error probable (CEP) of 10 meters.

CJ-10

The ChangJian-10 (Long Sword 10) is a cruise missile developed by China, based on the Hongniao missile family. It has a range of 2,200 km. Although not confirmed, it is suspected that the CJ-10 could carry nuclear warheads. An air-launched variant (named CJ-20) has also been developed.[60]

HongNiao missile family

There are three missiles in this family: the HN-1, HN-2, and HN-3. Reportedly based on the Kh-SD/65 missiles, the Hongniao (or Red Bird) missiles are some of the first nuclear-capable cruise missiles in China. The HN-1 has a range of 600 km, the HN-2 has a range of 1,800 km, and the HN-3 has a range of 3,000 km.[61][62][63]

ChangFeng missile family

There are 2 missiles in the Chang Feng (or Long Wind) family: CF-1 and CF-2. These are the first domestically developed long-range cruise missiles for China. The CF-1 has a range of 400 km while the CF-2 has a range of 800 km. Both variants can carry a 10 kt nuclear warhead.[61][62]

Sea-based weapons

The submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) stockpile of the People's Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is thought to be relatively new. China launched its first second-generation nuclear submarine in April 1981. The navy currently has a 1 Type 092 Xia class SSBN at roughly 8000 tons displacement. A second Type 092 was reportedly lost in an accident in 1985. The Type 092 is equipped with 12 JL-1 SLBMs with a range of 2150–2500 km. The JL-1 is a modified DF-21 missile. It is suspected that the Type 092 is being converted into a cruise missile submarine.

The Chinese navy has developed Type 094 ballistic missile submarine, open source satellite imagery has shown that at least 2 of these have been completed. This submarine will be capable of carrying 12 of the longer ranged, more modern JL-2s with a range of approximately 14000 km.

China is also developing the Type 096 submarine, claimed to be able to carry up to 24 JL-3 ballistic missiles each. Some Chinese sources states that the submarine is already undergoing trials.[64]

Nuclear Bomber Group

China's bomber force consists mostly of Chinese-made versions of Soviet aircraft. The People's Liberation Army Air Force has 120 H-6s (a variant of the Tupolev Tu-16). These bombers are outfitted to carry nuclear as well as conventional weapons. While the H-6 fleet is aging, it is not as old as the American B-52 Stratofortress.[50]:93–98 The Chinese have also produced the Xian JH-7 Flying Leopard fighter-bomber with a range and payload exceeding the F-111 (currently about 80 are in service) capable of delivering a nuclear strike. China has also bought the advanced Sukhoi Su-30 from Russia; currently, about 100 Su-30s (MKK and MK2 variants) have been purchased by China. The Su-30 is capable of carrying tactical nuclear weapons.[50]:102

China is alleged to be testing rumored new H-8 and Xian H-20 strategic bombers which are either described as an upgraded H-6 or an aircraft in the same class as the US B-2, able to carry nuclear weapons.[65][66][67]

Missile ranges

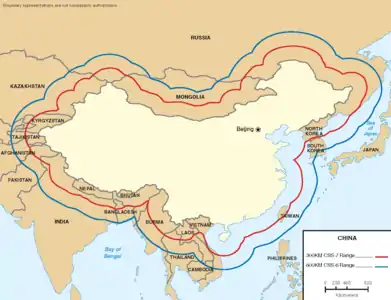

Maximum Ranges for China's Conventional SRBM Force (2006). Note: China currently is capable of deploying ballistic missile forces to support a variety of regional contingencies.

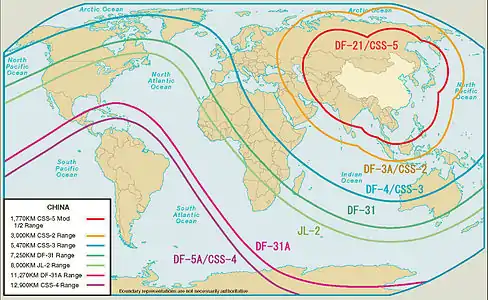

Maximum Ranges for China's Conventional SRBM Force (2006). Note: China currently is capable of deploying ballistic missile forces to support a variety of regional contingencies. Medium and Intercontinental Range Ballistic Missiles (2007). Note: China currently is capable of targeting its nuclear forces throughout the region and most of the world, including the continental United States. Newer systems, such as the DF-31, DF-31A, and JL-2, will give China a more survivable nuclear force.

Medium and Intercontinental Range Ballistic Missiles (2007). Note: China currently is capable of targeting its nuclear forces throughout the region and most of the world, including the continental United States. Newer systems, such as the DF-31, DF-31A, and JL-2, will give China a more survivable nuclear force.

See also

References

- "Fact Sheet:China: Nuclear Disarmament and Reduction of". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. April 27, 2004.

- Kristensen, Hans M; Korda, Matt (December 10, 2020). "Chinese nuclear forces, 2020". Taylor & Francis Online. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- "Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI): Nuclear Disarmament China, Estimated Destructive Power". Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), www.nti.org. February 13, 2017. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "Eliminating Nuclear Threats, A Practical Agenda for Global Policymakers, ICNND Report, 2009, Box 2-2". International Commission on Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament (ICNND), www.icnnd.org. November 2009. Archived from the original on June 25, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "DF-41: China's answer to the US BMD efforts | Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses". Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- "Nuclear weapon modernization continues but the outlook for arms control is bleak: New SIPRI Yearbook out now | SIPRI". www.sipri.org. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris (November–December 2011). "Chinese nuclear forces, 2011". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 67 (6): 81–87. Bibcode:2011BuAtS..67f..81K. doi:10.1177/0096340211426630. Archived from the original on November 16, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- "States Parties to the Chemical Weapons Convention". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved October 5, 2006.

- "Albania's Chemical Cache Raises Fears About Others" Archived 2019-11-17 at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post, 10 January 2005, page A01.

- Roland Everett Langford, Introduction to Weapons of Mass Destruction: Radiological, Chemical, and Biological, Wiley-IEEE, 2004

- William J Broad, Soviet Defector Says China Had Accident at a Germ Plant, The New York Times, April 5, 1999

- Leonard Spector, Chinese Assistance to Iran's Weapons of Mass Destruction and Missile Programs Archived 2009-06-11 at the Wayback Machine, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, September 12, 1996

- Nuclear Threat Initiative, Country Profile: China Archived 2011-08-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Burr, W.; Richelson, J. T. (2000–2001). "Whether to "Strangle the Baby in the Cradle": The United States and the Chinese Nuclear Program, 1960–64". International Security. 25 (3): 54–99. doi:10.1162/016228800560525. JSTOR 2626706.

- Jersild, Austin (October 8, 2013). "Sharing the Bomb among Friends: The Dilemmas of Sino-Soviet Strategic Cooperation". Cold War International History Project, Wilson Center. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- John Lewis and Litai Xue, China Builds the Bomb (Stanford University Press, 1991), 53, 61, 121.

- "CTBTO World Map". www.ctbto.org. Archived from the original on February 1, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- "Intelligence Community Damage Assessment on Chinese Espionage". Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- "Arms Control Association: Arms Control Today: Why China Won't Build U.S. Warheads". Web.archive.org. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 9, 2005. Retrieved December 11, 2005.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Report to Congress on Status of China, India and Pakistan Nuclear and Ballistic Missile Programs". Fas.org. Archived from the original on May 20, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- Archived July 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "1.doc" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 6, 2009. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 8, 2006. Retrieved December 6, 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Google Groups". groups.google.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 1, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- name=MOFA-factsheet-2004>"Fact Sheet:China: Nuclear Disarmament and Reduction of". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. April 27, 2004. Archived from the original on April 24, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "The ambiguous arsenal | thebulletin.org". Archived from the original on September 28, 2006. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 14, 2019. Retrieved April 4, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Fernandez, Yusuf. "Obama against Chinese Nuclear Great Wall". PressTV. Archived from the original on March 26, 2013. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- Minnick, Wendell (January 5, 2013). "New U.S. Law Seeks Answers On Chinese Nuke Tunnels". Defense News. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- Hans M. Kristensen (December 3, 2011). "No, China Does Not Have 3,000 Nuclear Weapons". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 1, 2013. Retrieved June 21, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 28, 2015. Retrieved June 21, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Kristensen, Hans. "STRATCOM Commander Rejects High Estimates for Chinese Nuclear Arsenal." Archived 2013-01-30 at the Wayback Machine FAS, 22 August 2012.

- Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People.s Republic of China 2013 (PDF) (Report). Office of the Secretary of Defense. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- Kaegan McGrath and Vasileios Savvidis (February 1, 2009). "UNSC Resolution 1887: Packaging Nonproliferation and Disarmament at the United Nations". Nuclear Threat Initiative. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- "Statement on security assurances issued on 5 April 1995 by the People's Republic of China". United Nations. April 6, 1995. S/1995/265. Retrieved September 20, 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "China Publishes White Paper on Arms Control". China.org.cn. September 1, 2005. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved October 15, 2013.

- Hugh Chalmers (January 2014). A Disturbance in the Force (PDF) (Report). Royal United Services Institute. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- "122 countries adopt 'historic' UN treaty to ban nuclear weapons". CBC News. July 7, 2017. Archived from the original on August 14, 2019. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- Gramer, Robbie; Detsch, Jack (April 29, 2020). "Trump Fixates on China as Nuclear Arms Pact Nears Expiration". Foreign Policy. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- Pifer, Steven (July 1, 2020). "Unattainable conditions for New START extension?". The Brookings Institution. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- Matthew Kroenig, Exporting the Bomb: Technology Transfer and the Spread of Nuclear Weapons (Cornell University Press, 2010), 1.

- "A Letter Written by A.Q. Khan to His Wife". March 27, 2015. Archived from the original on August 6, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- Etzioni, Amitai, "MAR: A Model for US-China Relations," The Diplomat, September 20, 2013, Archived 2017-07-20 at the Wayback Machine.

- "IISS Military Balance 2010". Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- Office of the Secretary of Defense – Annual Report to Congress: Military Power of the People's Republic of China 2010 (PDF) Archived 2015-03-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Kristensen, Hans M; Robert S. Norris; Matthew G. McKinzie. Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning Archived 2019-08-03 at the Wayback Machine. Federation of American Scientists and Natural Resources Defense Council, November 2006.

- Kristensen, Hans M. (19 April 2013). "Chinese ICBM Force Leveling Out?". Strategic Security Blog. Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- MINNICK, WENDELL (November 11, 2013). "US Report: 1st Sub-launched Nuke Missile Among China's Recent Strides". defensenews.com. Gannett Government Media Corporation. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- Tweed, David (December 9, 2014). "China Takes Nuclear Weapons Underwater Where Prying Eyes Can't See". bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2014. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- Archived May 25, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- "DongFeng 31A (CSS-9) Intercontinental Ballistic Missile". SinoDefence.com. Archived from the original on April 6, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "U.S. Lawmaker Warns of China's Nuclear Strategy – China Digital Times (CDT)". Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- "straitstimes.com". Archived from the original on October 16, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- China Builds Underground 'Great Wall' Against Nuke Attack Archived 2020-02-16 at the Wayback Machine The Chosun Ilbo, Dec. 14, 2009.

- U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Military Power of the People’s Republic of China, 2006, May 23, 2006, pp. 26, 27.

- "Sword −20 cruise missiles loaded on to H-6M bombers". Global Military. December 10, 2009. Archived from the original on December 11, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- John Pike. "Land-Attack Cruise Missiles (LACM)". Globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on March 5, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Land-Attack Cruise Missile (LACM)". SinoDefence.com. May 7, 2007. Archived from the original on January 10, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "HN-2". CSIS Missile Threat. Archived from the original on November 4, 2016. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Global Security Newswire". NTI. Archived from the original on August 30, 2008. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "外媒炒作中国首架轰-8隐形战略轰炸机问世(图)_新浪军事_新浪网". Mil.news.sina.com.cn. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "英国简氏称中国正在研发轰-8型隐形轰炸机_军事频道_新华网". News.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on March 25, 2009. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- "Google Translate". November 11, 2008. Archived from the original on November 13, 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

Further reading

- Federation of American Scientists et al. (2006). Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning

- China Nuclear Forces Guide Federation of American Scientists

External links

- CSIS Missile Threat – China

- Archival Documents on the Chinese Nuclear Program at The Wilson Center Digital Archive

- Chinese Nuclear Weapon Testing Video at sonicbomb.com

- Status of Nuclear Powers and Their Nuclear Capabilities, Federation of American Scientists

- Nuclear Threat Initiative on China

- Chinese Defence Today

- Jeffrey Lewis, "The ambiguous arsenal", Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, May/June 2005.

- Defense Estimative Brief, Nuclear Weapons Systems in China, Defense Intelligence Agency, 24 April 1984

- Report to Congress on Status of China, India and Pakistan Nuclear and Ballistic Missile Programs, United States National Security Council, July 28, 1993

- Nuclear Files.org Information on the background of nuclear weapons in China

- Annotated bibliography for the Chinese nuclear weapons program from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues