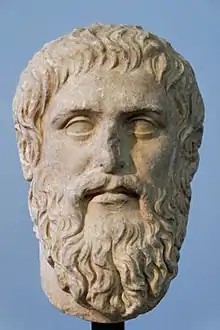

Philosopher king

According to Plato, a philosopher king is a ruler who possesses both a love of wisdom, as well as intelligence, reliability, and a willingness to live a simple life. Such are the rulers of his utopian city Kallipolis. For such a community to ever come into being, "philosophers [must] become kings…or those now called kings [must]…genuinely and adequately philosophize" (Plato, The Republic, 5.473d).

| Part of a series on |

| Platonism |

|---|

|

| Allegories and metaphors |

| Related articles |

| Related categories |

|

► Plato |

|

In Book VI of The Republic

Plato defined a philosopher firstly as its eponymous occupation: "wisdom-lover." He then distinguishes between one who loves true knowledge (as opposed to mere experience or education) by saying that the philosopher is the only person who has access to ideas – the archetypal entities that exist behind all representations of the form (such as Beauty itself as opposed to any one particular instance of beauty). It is next and in support of the idea that philosophers are the best rulers that Plato fashions the Ship of State metaphor, one of his most often cited ideas (along with his allegory of the cave): a "true pilot must of necessity pay attention to the seasons, the heavens, the stars, the winds, and everything proper to the craft if he is really to rule a ship" (The Republic, 6.488d).

Examples

Magna Graecia

Archytas was a Pythagorean philosopher and political leader in the ancient Greek city of Tarentum, in Italy. He was a close friend of Plato, and some scholars assert that he may have been an inspiration for Plato's concept of a philosopher-king.

Dion of Syracuse was a disciple of Plato. He overthrew the tyrant Dionysius II of Syracuse and was installed as leader in the city, only to be made to leave by the Syracusans who were unhappy with his opposition to democratic reforms. He was later re-invited to the city, where he attempted to establish an aristocracy along Platonic lines, but he was assassinated by plotters in the pay of the former tyrant.

Roman Empire

Marcus Aurelius was the first prominent example of a philosopher king. His Stoic tome Meditations, written in Greek while on campaign between 170 and 180, is still revered as a literary monument to a philosophy of service and duty, describing how to find and preserve equanimity in the midst of conflict by following nature as a source of guidance and inspiration.

Sasanian Empire

In the west, some considered Khosrow I as the philosopher king. He was admired, both in Persia and elsewhere, for his character, virtues, and knowledge of Greek philosophy.[1][2][3]

Hungary

Matthias Corvinus (1443–1490), who was king of Hungary and Croatia from 1458, was influenced by the Italian Renaissance and strongly endeavored to follow in practice the model and ideas of the philosopher-king as described in The Republic.[4]

Modern Iran

Ayatollah Khomeini is said to have been inspired by the Platonic vision of the philosopher king while in Qum in the 1920s when he became interested in Islamic mysticism and Plato's Republic. As such, it has been speculated that he was inspired by Plato's philosopher king, and subsequently based elements of his Islamic republic on it, despite it being a republic which deposed the former Pahlavi dynasty.[5]

Criticism

Karl Popper blamed Plato for the rise of totalitarianism in the 20th century, seeing Plato's philosopher kings, with their dreams of "social engineering" and "idealism", as leading directly to Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin (via Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Karl Marx respectively).[6]

References

- Axworthy, Michael (2008). Iran: Empire of the Mind: A History from Zoroaster to the Present Day. Penguin Adult. p. 65. ISBN 9780141036298.

- Wākīm, Salīm (1987). Iran, the Arabs, and the West: the story of twenty-five centuries. Vantage Press. p. 92.

- Rose, Jenny (2011). Zoroastrianism: An Introduction. I.B.Tauris. p. 133. ISBN 9781848850880.

- "Marsilio Ficino: Magnus of the Renaissance, Shaper of Leaders". integralleadershipreview.com. Feature Articles / March 2007.

- Anderson, Raymond H. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, 89, the Unwavering Iranian Spiritual Leader. The New York Times, 4 June 1989.

- Popper, Karl. The Poverty of Historicism. Routledge, 2002.

Bibliography

- Desmond, William D. Philosopher-Kings of Antiquity. Continuum / Bloomsbury, 2011.

- C.D.C. Reeve, Philosopher-Kings: The Argument of Plato's Republic, Princeton University Press, 1988.

- Plato (1991). The Republic: the complete and unabridged Jowett translation. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-73387-6.

External links

- Text of section of The Republic pertaining to philosopher-kings.

- Podcast #14: Mick Mulroy, Philosopher Kings, Ethics, and Wisdom.