Platonic love

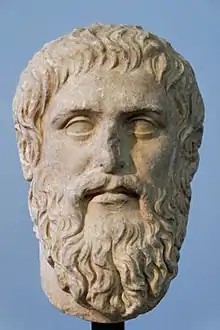

Platonic love (often lower-cased as platonic love)[1] is a type of love that is not sexual. It is named after Greek philosopher Plato, though the philosopher never used the term himself. Platonic love as devised by Plato concerns rising through levels of closeness to wisdom and true beauty from carnal attraction to individual bodies to attraction to souls, and eventually, union with the truth. This is the ancient, philosophical interpretation.[2]

Relationships (Outline) |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Love |

|---|

Red-outline heart icon |

Classical philosophical interpretation

Platonic love is examined in Plato's dialogue, the Symposium, which has as its topic the subject of love, or more generally the subject of Eros. It explains the possibilities of how the feeling of love began and how it has evolved, both sexually and non-sexually, and defines genuine platonic love as inspiring a person's mind and soul and directing their attention towards spiritual matters. Of particular importance is the speech of Socrates, who attributes to the prophetess Diotima an idea of platonic love as a means of ascent to contemplation of the divine, an ascent is known as the "Ladder of Love". For Diotima and Plato generally, the most correct use of love of human beings is to direct one's mind to love of divinity. Socrates defines love based on separate classifications of pregnancy (to bear offspring); pregnancy of the body, pregnancy of the soul, and direct connection to existence. Pregnancy of the body results in human children. Pregnancy of the soul, the next step in the process, produces "virtue"—which is the soul (truth) translating itself into material form.[3]

"... virtue for the Greeks means self-sameness ... in Plato's terms, Being or idea."(106)[3]

Eros

Pausanias, in Plato's Symposium (181b–182a), defines two types of the love known as "Eros": vulgar Eros, or earthly love, and divine Eros, or divine love. Pausanias defines vulgar Eros as material attraction towards a person's beauty for the purposes of physical pleasure and reproduction, and divine Eros as starting from physical attraction but transcending gradually to love for supreme beauty, placed on a similar level to the divine. This concept of divine Eros was later transformed into the term "platonic love".

Vulgar Eros and divine Eros were both considered to be connected, and part of the same continuous process of pursuing perfection of one's being,[4] with the purpose of mending one's human nature and eventually reaching a point of unity where there is no longer an aspiration or need to change.[5]

"Eros is ... a moment of transcendence ... in so far as the other can never be possessed without being annihilated in its status as the other, at which point both desire and transcendence would cease ... (84)[5]

Eros as a god

In the Symposium, Eros is discussed as a Greek god—more specifically, the king of the gods, with each guest of the party giving a eulogy in praise of Eros.[4]

Virtue

Virtue, according to Greek philosophy, is the concept of how closely reality and material form equates good, positive, or benevolent. This can be seen as a form of linguistic relativity.

Some modern authors' perception of the terms "virtue" and "good" as they are translated into English from the Symposium are a good indicator of this misunderstanding. In the following quote, the author simplifies the idea of virtue as simply what is "good".

"... what is good is beautiful, and what is beautiful is good ..."[6]

Ladder of Love

The Ladder of Love is named as such because it relates each step toward Being itself as consecutive rungs of a ladder. Each step closer to the truth further distances love from beauty of the body toward love that is more focused on wisdom and the essence of beauty.[3]

The ladder starts with carnal attraction of body for body, progressing to a love for body and soul. Eventually, in time, with consequent steps up the ladder, the idea of beauty is eventually no longer connected with a body, but entirely united with Being itself.[4]

"[...] decent human beings must be gratified, as well as those that are not as yet decent, so that they might become more decent; and the love of the decent must be preserved."[4] (187d, 17) - Eryximachus' "completion" of Pausanias' speech on Eros

Tragedy and comedy

Plato's Symposium defines two extremes in the process of platonic love; the entirely carnal and the entirely ethereal. These two extremes of love are seen by the Greeks in terms of tragedy and comedy. According to Diotima in her discussion with Socrates, for anyone to achieve the final rung in the Ladder of Love, they would essentially transcend the body and rise to immortality—gaining direct access to Being. Such a form of love is impossible for a mortal to achieve.[3]

What Plato describes as "pregnancy of the body" is entirely carnal and seeks pleasure and beauty in bodily form only. This is the type of love, that, according to Socrates, is practiced by animals.[4]

"Now, if both these portraits of love, the tragic and the comic, are exaggerations, then we could say that the genuine portrayal of Platonic love is the one that lies between them. The love described as the one practiced by those who are pregnant according to the soul, who partake of both the realm of beings and the realm of Being, who grasp Being indirectly, through the mediation of beings, would be a love that Socrates could practice."[3]

Tragedy

Diotima considers the carnal limitation of human beings to the pregnancy of the body to be a form of tragedy, as it separates someone from the pursuit of truth. One would be forever limited to beauty of the body, never being able to access the true essence of beauty.[3]

Comedy

Diotima considers the idea of a mortal having direct access to Being to be a comic situation simply because of the impossibility of it. The offspring of true virtue would essentially lead to a mortal achieving immortality.[6]

Historical views of platonic love

In the Middle Ages, new interest in the works of Plato, his philosophy and his view of love became more popular, spurred on by Georgios Gemistos Plethon during the Councils of Ferrara and Firenze in 1438–1439. Later in 1469, Marsilio Ficino put forward a theory of neo-platonic love, in which he defined love as a personal ability of an individual, which guides their soul towards cosmic processes, lofty spiritual goals and heavenly ideas.[7] The first use of the modern sense of platonic love is considered to be by Ficino in one of his letters.

Though Plato's discussions of love originally centered on relationships which were sexual between members of the same sex, scholar Todd Reeser studies how the meaning of platonic love in Plato's original sense underwent a transformation during the Renaissance, leading to the contemporary sense of nonsexual heterosexual love.[8]

The English term "platonic" dates back to William Davenant's The Platonic Lovers, performed in 1635, a critique of the philosophy of platonic love which was popular at Charles I's court. The play was derived from the concept in Plato's Symposium of a person's love for the idea of good, which he considered to lie at the root of all virtue and truth. For a brief period, platonic love was a fashionable subject at the English royal court, especially in the circle around Queen Henrietta Maria, the wife of King Charles I. Platonic love was the theme of some of the courtly masques performed in the Caroline era, though the fashion for this soon waned under pressures of social and political change.

Seven types of love

Throughout these eras, platonic love was slowly categorized into seven different classical definitions. These were:

- Eros sexual or passionate love, or a modern perspective of romantic love.

- Philia the love of friendship or goodwill, often met with mutual benefits that can also be formed by companionship, dependability, and trust.

- Storge the love found between parents and children, often a unilateral love.

- Agape the universal love, consisting of love for strangers, nature, or God.

- Ludus playful and uncommitted love, intended for fun with no resulting consequences.

- Pragma love founded on duty and reason, and one's longer-term interests.

- Philautia self-love, both healthy or unhealthy; unhealthy if one places oneself above the gods (to the point of hubris), and healthy if it is used to build self-esteem and confidence.

Despite the variety and number of definitions, the different distinctions between types of love were not considered concrete and mutually exclusive, and were often considered to blend into one another at certain points.[9]

Modern interpretation

Definition

"Platonic love in its modern popular sense is an affectionate relationship into which the sexual element does not enter, especially in cases where one might easily assume otherwise."[10] "Platonic lovers function to underscore a supportive role where the friend sees [their] duty as the provision of advice, encouragement, and comfort to the other person ... and do not entail exclusivity."[11]

Complications

One of the complications of platonic love lies within the persistence of the use of the title itself "platonic love" versus the use of "friend". It is the use of the word love that directs us towards a deeper relationship than the scope of a normal friendship.

Secondly, a study by Hause and Messman states: "The most popular reasons for retaining a platonic relationship of the opposite sex (or sex of attraction) was to safeguard a relationship, followed by not attracted, network disapproval, third party, risk aversion, and time out." This points to the fact that the title of platonic love in most cases is actually a title-holder to avoid sexual interaction between knowing and consenting friends, with mutual or singular sexual interest and/or tension existing.

See also

.png.webp)

- Asexuality

- Attraction

- Bromance

- Casual dating

- Childhood sweetheart

- Emotional affair

- Fraternization

- Greek love

- Heterosociality

- Homosexuality

- Infatuation

- Interpersonal attraction

- Interpersonal communication

- Intimate relationship

- Puppy love

- Relationship anarchy

- Romantic friendship

- Soulmate

- Womance

- Work spouse

Notes

- "8.60: When not to capitalize". The Chicago Manual of Style (16th [electronic] ed.). Chicago University Press. 2010.

- Mish, F (1993). Merriam-Webster's collegiate dictionary: Tenth Edition. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. ISBN 978-08-7779-709-8.

- Rojcewicz, R. (1997). Platonic love: dasein's urge toward being. Research in Phenomenology, 27(1), 103.

- Benardete, S. (1986). Plato's Symposium. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-04275-8.

- Miller, P. A. (2013). Duras and platonic love: The erotics of substitution. Comparatist, 3783-104.

- Herrmann, F. (2013). Dynamics of vision in Plato's thought. Helios, 40(1/2), 281-307.

- De Amore, Les Belles Lettres, 2012

- Reeser, T. (2015). Setting Plato Straight: Translating Platonic Sexuality in the Renaissance. Chicago.

- "These Are the 7 Types of Love". Psychology Today. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- "Platonic love". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- Messman, SJ (2000). "Motives to Remain Platonic, Equity, and the Use of Maintenance Strategies in Opposite-Sex Friendships". Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 17: 67–94. doi:10.1177/0265407500171004.

References

- Dall'Orto, Giovanni (January 1989). "'Socratic Love' as a Disguise for Same-Sex Love in the Italian Renaissance". Journal of Homosexuality. 16 (1–2): 33–66. doi:10.1300/J082v16n01_03.

- Gerard, Kent; Hekma, Gert (1989). The Pursuit of Sodomy: Male Homosexuality in Renaissance and Enlightenment Europe. New York: Harrington Park Press. ISBN 978-0-918393-49-4.

- K. Sharpe, Criticism and Compliment. Cambridge, 1987, ch. 2.

- T. Reeser, Setting Plato Straight: Translating Platonic Sexuality in the Renaissance. Chicago, 2015.

- Burton, N., MD (25 June 2016). These Are the 7 Types of Love. Psychology Today. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- Messman, S. J., Hause, D. J., & Hause, K. S. (2000). "Motives to Remain Platonic, Equity, and the Use of Maintenance Strategies in Opposite-Sex Friendships." Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 17 (1), 67–94. doi:10.1177/0265407500171004

- Mish, F. C. (Ed.). (1993). Merriam-Webster's collegiate dictionary: Tenth Edition. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, Inc. ISBN 08-7779-709-9.

- Rojcewicz, R. (1997). "Platonic love: dasein's urge toward being." Research in Phenomenology, 27 (1), 103.

- Miller, P. A. (2013). "Duras and platonic love: The erotics of substitution." Comparatist, 37 83–104.

- Benardete, S. (1986). Plato's Symposium. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-04275-8.

- Herrmann, F. (2013). "Dynamics of vision in Plato's thought." Helios, 40 (1/2), 281–307.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Platonic Love. |