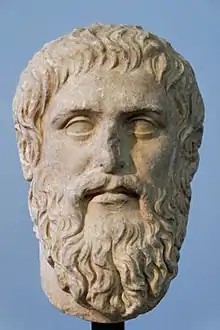

Platonic idealism

Platonic idealism usually refers to Plato's theory of forms or doctrine of ideas. It holds that only ideas encapsulate the true and essential nature of things, in a way that the physical form cannot. We recognise a tree, for instance, even though its physical form may be most untreelike. The treelike nature of a tree is therefore independent of its physical form. Plato's idealism evolved from Pythagorean philosophy, which held that mathematical formulas and proofs accurately describe the essential nature of all things, and these truths are eternal. Plato believed that because knowledge is innate and not discovered through experience, we must somehow arrive at the truth through introspection and logical analysis, stripping away false ideas to reveal the truth.

| Part of a series on |

| Platonism |

|---|

|

| Allegories and metaphors |

| Related articles |

| Related categories |

|

► Plato |

|

Overview

Some commentators hold that Plato argued that truth is an abstraction. In other words, we are urged to believe that Plato's theory of ideals is an abstraction, divorced from the so-called external world, of modern European philosophy, despite the fact Plato taught that ideals are ultimately real, and different from non-ideal things—indeed, he argued for a distinction between the ideal and non-ideal realm.

These commentators speak thus: for example, a particular tree, with a branch or two missing, possibly alive, possibly dead, and with the initials of two lovers carved into its bark, is distinct from the abstract form of Tree-ness.[1] A Tree[1] is the ideal that each of us holds that allows us to identify the imperfect reflections of trees all around us.

Plato gives the divided line as an outline of this theory. At the top of the line, the Form of the Good[1] is found, directing everything underneath.

Some contemporary linguistic philosophers construe "Platonism" to mean the proposition that universals exist independently of particulars (a universal is anything that can be predicated of a particular).

Platonism is an ancient school of philosophy, founded by Plato; at the beginning, this school had a physical existence at a site just outside the walls of Athens called the Academy, as well as the intellectual unity of a shared approach to philosophizing.

Platonism is usually divided into three periods:

Plato's students used the hypomnemata as the foundation to his philosophical approach to knowledge. The hypomnemata constituted a material memory of things read, heard, or thought, thus offering these as an accumulated treasure for rereading and later meditation. For the Neoplatonist they also formed a raw material for the writing of more systematic treatises in which were given arguments and means by which to struggle against some defect (such as anger, envy, gossip, flattery) or to overcome some difficult circumstance (such as a mourning, an exile, downfall, disgrace).

Platonism is considered to be, in mathematics departments the world over, the predominant philosophy of mathematics, especially regarding the foundations of mathematics.

One statement of this philosophy is the thesis that mathematics is not created but discovered. A lucid statement of this is found in an essay written by the British mathematician G. H. Hardy in defense of pure mathematics.[2][3]

The absence in this thesis of clear distinction between mathematical and non-mathematical "creation" leaves open the inference that it applies to allegedly creative endeavors in art, music, and literature.

It is unknown if Plato's ideas of idealism have some earlier origin, but Plato held Pythagoras in high regard, and Pythagoras as well as his followers in the movement known as Pythagoreanism claimed the world was literally built up from numbers, an abstract, absolute form.

See also

Notes

- In the field of philosophy, it has been customary to capitalize words that are concept names, such as "Search for Truth" (or "Goodness" or "Man"). Common ideals are Truth, Kindness, and Beauty. Such capitalization is not common in science, and hence, concepts such as "accuracy" and "gravity" are not often capitalized in scientific writing, but could be capitalized in philosophical papers.

- "In Defense of Pure Mathematics". American Scientist. 2017-02-06. Retrieved 2018-06-10.

- Hardy, G. H. (1992-01-31). A Mathematician's Apology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521427067.

References

- "Plato And The Theory Of Forms", Tim Ruggiero, Philosophical Society, July 2002, webpage: PhilosophicalSociety-Forms.

- Plato's Theory of Ideas, by W. D. Ross.

- Platonism and the Spiritual Life, by George Santayana.