Royal Collection

The Royal Collection of the British royal family is the largest private art collection in the world.[7][8]

The Adoration of the Kings, studio of Paolo Veronese (c. 1573–1666)[1]

Venus and Adonis Embracing, Italian School (c. 1580–1620)[2]

The Flood, Jacopo Bassano (c. 1570)[3]

Diligence, Italian School (c. 1530)[4]

Charles I with M. de St Antoine, after Anthony van Dyck (1700s)[5]

Fame, Italian School (c. 1530)[6]

Spread among 13 occupied and historic royal residences in the United Kingdom, the collection is owned by Elizabeth II and overseen by the Royal Collection Trust. The Queen owns some of the collection in right of the Crown and some as a private individual. It is made up of over one million objects,[9] including 7,000 paintings, over 150,000 works on paper,[10] this including 30,000 watercolours and drawings,[11] and about 450,000 photographs,[12] as well as tapestries, furniture, ceramics, textiles, carriages, weapons, armour, jewellery, clocks, musical instruments, tableware, plants, manuscripts, books, and sculptures.

Some of the buildings which house the collection, like Hampton Court Palace, are open to the public and not lived in by the Royal Family, whilst others, like Windsor Castle and Kensington Palace, are both residences and open to the public. The Queen's Gallery at Buckingham Palace in London was built specially to exhibit pieces from the collection on a rotating basis. There is a similar art gallery next to the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh, and a Drawings Gallery at Windsor Castle. The Crown Jewels are on public display in the Jewel House at the Tower of London.

About 3,000 objects are on loan to museums throughout the world, and many others are lent on a temporary basis to exhibitions.[9]

History

Few items from before Henry VIII survive. The most important additions were made by Charles I, a passionate collector of Italian paintings and a major patron of Van Dyck and other Flemish artists. He purchased the bulk of the Gonzaga collection from the Duchy of Mantua. The entire Royal Collection, which included 1,500 paintings and 500 statues,[13] was sold after Charles's execution in 1649. The 'Sale of the Late King's Goods' at Somerset House raised £185,000 for the English Republic. Other items were given away in lieu of payment to settle the king's debts.[14] A number of pieces were recovered by Charles II after the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, and they form the basis for the collection today. The Dutch Republic also presented Charles with the Dutch Gift of 28 paintings, 12 sculptures, and a selection of furniture. He went on to buy many paintings and other works.

George III was mainly responsible for forming the collection's outstanding holdings of Old Master drawings; large numbers of these, and many Venetian paintings including over 40 Canalettos, joined the collection when he bought the collection of Joseph "Consul Smith", which also included a large number of books.[16] Many other drawings were bought from Alessandro Albani, cardinal and art dealer in Rome.[17]

George IV shared Charles I's enthusiasm for collecting, buying up large numbers of Dutch Golden Age paintings and their Flemish contemporaries. Like other English collectors, he took advantage of the great quantities of French decorative art on the London market after the French Revolution, and is mostly responsible for the collection's outstanding holdings of 18th-century French furniture and porcelain, especially Sèvres. He also bought much contemporary English silver, and many recent and contemporary English paintings.[18] Queen Victoria and her husband Albert were keen collectors of contemporary and old master paintings.

Many objects have been given from the collection to museums, especially by George III and Victoria and Albert. In particular, the King's Library formed by George III with the assistance of his librarian Frederick Augusta Barnard, consisting of 65,000 printed books, was given to the British Museum, now the British Library, where they remain as a distinct collection.[19] He also donated the "Old Royal Library" of some 2,000 manuscripts, which are still segregated as the Royal manuscripts.[20] The core of this collection was the purchase by James I of the related collections of Humphrey Llwyd, Lord Lumley, and the Earl of Arundel.[21] Prince Albert's will requested the donation of a number of mostly early paintings to the National Gallery, London, which Queen Victoria fulfilled.[22]

Modern era

Throughout the reign of Elizabeth II (1952–present), there have been significant additions to the collection through judicious purchases, bequests, and gifts from nation states and official bodies.[23] Since 1952, approximately 2,500 works have been added to the Royal Collection.[14] The Commonwealth is strongly represented in this manner: an example is 75 contemporary Canadian watercolours that entered the collection between 1985 and 2001 as a gift from the Canadian Society of Painters in Water Colour.[24] Modern art acquired by Elizabeth II includes pieces by Sir Anish Kapoor and Andy Warhol.[14]

In 1987 a new department of the Royal Household was established to oversee the Royal Collection, and it was financed by the commercial activities of Royal Collection Enterprises, a limited company. Before then, it was maintained using the monarch's official income paid by the Civil List. Since 1993 the collection has been funded by entrance fees to Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace.[25]

Collection

.JPG.webp)

A computerised inventory of the collection was started in early 1991,[28] and it was completed in December 1997.[29] The full inventory is not available to the public, though catalogues of parts of the collection – especially paintings – have been published, and a searchable database on the Royal Collection website is increasingly comprehensive,[30] with "271,697 items found" by late 2020.[31]

About a third of the 7,000 paintings in the collection are on view or stored at buildings in London which fall under the remit of the Historic Royal Palaces agency: the Tower of London, Hampton Court Palace, Kensington Palace, Banqueting House (Whitehall), and Kew Palace.[32] The Jewel House and Martin Tower at the Tower of London also house the Crown Jewels. A rotating selection of art, furniture, jewellery, and other items considered to be of the highest quality is shown at the Queen's Gallery, a purpose-built exhibition centre near Buckingham Palace.[33] Many objects are displayed in the palace itself, the state rooms of which are open to visitors for much of the year, as well as in Windsor Castle, Holyrood Palace in Edinburgh, the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, and Osborne House on the Isle of Wight. Some works are on long-term or permanent loan to museums and other places; the most famous of these are the Raphael Cartoons, in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London since 1865.[34]

Paintings, prints and drawings

The collection's holdings of Western fine art are among the largest and most important assemblages in existence, with works of the highest quality, and in many cases artists whose works cannot be fully understood without a study of the holdings contained within the Royal Collection. There are over 7,000 paintings, spread across the Royal residences and palaces. The collection does not claim to provide a comprehensive, chronological survey of Western fine art but it has been shaped by the individual tastes of kings, queens and their families over the last 500 years.

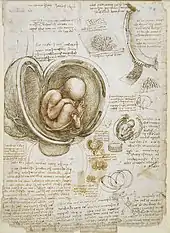

The prints and drawings collection is based in the Print Room, Windsor, and is exceptionally strong, with famous holdings of drawings by Leonardo da Vinci (550), Raphael, Michelangelo and Hans Holbein the Younger (85). A large part of the Old Master drawings were acquired by George III.[35] Starting in early 2019, 144 of Leonardo daVinci's drawings from the Collection went on display in 12 locations in the UK.[36] From May to October that year, 200 of the drawings were on display in the Queen's Gallery at Buckingham Palace.[37]

- Benjamin West – at least 60 paintings

- Abraham Bloemaert – at least 1 painting

- Gerard ter Borch – at least 2 paintings

- Jan Dirksz Both – at least at least 1 painting

- Jan de Bray – at least at least 1 painting

- Hendrick ter Brugghen – at least 1 painting

- Aelbert Cuyp – at least 7 paintings

- Gerrit Dou – at least 4 paintings

- Frans Hals – at least 1 painting

- Hugo van der Goes – at least 1 painting

- Maarten van Heemskerck – at least 2 paintings

- Jan van der Heyden – at least 2 paintings

- Meyndert Hobbema – at least 2 paintings

- Melchior d'Hondecoeter – at least 4 paintings

- Gerard van Honthorst – at least 6 paintings

- Pieter de Hooch – at least 3 paintings

- Nicolaes Maes – at least 1 painting

- Jan Mertens the Younger – at least 1 painting

- Gabriel Metsu – at least 1 painting

- Daniël Mijtens – at least 9 paintings

- Adriaen van Ostade – at least 5 paintings

- Rembrandt – at least 6 paintings

- Salomon van Ruysdael – at least 1 painting

- Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael – at least 1 painting

- Jan Steen – at least 7 paintings

- Adriaen van de Velde – at least 4 paintings

- Willem van de Velde the Younger – at least 7 paintings

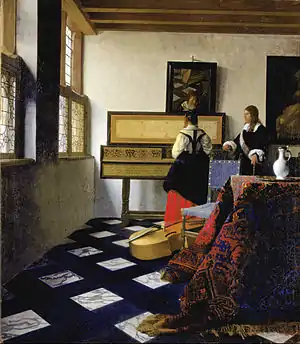

- Johannes Vermeer – at least 1 painting (see image)

- Jan Weenix – at least 1 painting:

- Adriaen van der Werff – at least 1 painting

- Philip Wouwerman – at least 5 paintings

- William Beechey – at least 17 paintings

- Thomas Gainsborough – at least 33 paintings, including a rare mythological work, Diana and Actaeon

- William Hogarth – at least 3 paintings

- John Hoppner – at least 7 paintings

- Cornelis Janssens van Ceulen – at least 2 paintings

- Sir Godfrey Kneller – at least 15 paintings

- Edwin Henry Landseer – at least 100 paintings and drawings

- Thomas Lawrence – at least 50 paintings

- Peter Lely – at least 20 paintings

- Joshua Reynolds – at least 20+ paintings

- George Stubbs – at least 18 paintings

- Jan Brueghel the Elder – at least 1 painting

- Pieter Bruegel the Elder – at least 1 painting

- Denys Calvaert – at least 1 painting

- Joos van Cleve – at least 4 paintings

- Pieter van Coninxloo – at least 1 painting

- Anthony van Dyck – at least 26 paintings

- Frans Francken the Younger – at least 1 painting

- Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger – at least 1 painting

- Frans Hals – at least 1 painting

- Jan Mabuse – at least 1 painting

- Quentin Matsys – at least 1 painting

- Hans Memling – at least 1 painting

- Frans Pourbus the younger – at least 2 paintings

- Jan Provoost – at least 1 painting

- Peter Paul Rubens – at least 13 paintings, 5 drawings (see image)

- David Teniers the Younger – at least 27 paintings

- François Clouet – at least 3 paintings

- Jean Clouet – at least 1 painting, 1 miniature

- Hippolyte Delaroche – at least 3 paintings

- Gaspard Dughet – at least 3 paintings

- Nicolas de Largillière – at least 1 painting

- Jean-Étienne Liotard – at least 16 paintings

- Claude Lorrain – at least 5 paintings

- Claude Monet – at least 1 painting

- Louis Le Nain – at least 1 painting

- Jean-Baptiste Pater – at least 4 paintings

- Nicolas Poussin – at least A large collection of his drawings at Windsor, second only to that in the Musée du Louvre

- Eustache Le Sueur – at least 1 painting

- Georges de La Tour – at least 1 painting

- Simon Vouet – at least 1 painting

- Albrecht Dürer – at least 1 painting

- Hans Holbein the Younger – at least 7 paintings, 80 drawings and 5 miniatures

- Lucas Cranach the Elder – at least 5 paintings

- Lucas Cranach the Younger – at least 1 painting

- Georg Pencz – at least 1 painting

- Franz Xaver Winterhalter – at least 120 paintings, 20 drawings & watercolours

- Johann Zoffany – at least 17 paintings

- Niccolò dell'Abbate – at least 1 painting

- Alessandro Allori – at least 1 painting

- Fra Angelico – at least 1 painting

- Jacopo Bassano – at least 6 paintings

- Leandro Bassano – at least 3 paintings

- Giovanni Bellini – at least 1 painting

- Gian Lorenzo Bernini – at least 50 drawings

- Francesco Borromini – at least 100 drawings

- Bronzino (Agnolo di Cosimo) – at least 1 painting

- Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal) – at least 50 paintings and 140 drawings

- Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio) – at least 2 paintings

- Polidoro da Caravaggio – at least 9 paintings

- Giovanni Cariani – at least 2 paintings

- Luca Carlevaris – at least 4 paintings

- Agostino, Annibale and Ludovico Carracci – at least 5 paintings, more than 350 drawings

- Cima da Conegliano – at least 1 painting

- Jacopo di Cione – at least 1 painting

- Antonio da Correggio – at least 2 paintings

- Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione – at least 260 drawings

- Bernardo Daddi – at least 1 painting

- Carlo Dolci – at least 1 painting

- Domenichino (Domenico Zampieri) – at least 1 painting, as well as 1,700 drawings in 34 albums, the Royal Collection's largest holdings by a single artist

- Dosso Dossi – at least 2 paintings

- Duccio – at least 1 painting

- Gentile da Fabriano – at least 1 painting

- Girolamo Forabosco – at least 1 painting

- Domenico Fetti – at least 14 paintings

- Lattanzio Gambara – at least 8 paintings

- Benvenuto Tisi (Il Garofalo) – at least 1 painting

- Raffaellino del Garbo – at least 1 painting

- Artemisia Gentileschi – at least 1 painting

- Orazio Gentileschi – at least 2 paintings

- Luca Giordano – at least 12 paintings

- Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) – at least 1 painting, and largest group of Guercino drawings in the world, some 400 sheets, as well as 200 by his assistants and 200 other works[39]

- Leonardo da Vinci – at least 600 drawings, finest collection of Leonardo drawings in the world[40]

- Bernardino Licinio – at least 4 paintings

- Pietro Longhi – at least 2 paintings

- Lorenzo Lotto – at least 3 paintings – at least Portrait of Andrea Odoni

- Andrea Mantegna – at least 9 canvases known as The Triumphs of Caesar

- Ludovico Mazzolino – at least 1 painting

- Michelangelo – at least 20 drawings

- Parmigianino (Francesco Mazzola) – at least 2 paintings and 30 drawings

- Pietro Perugino – at least 1 painting

- Francesco Pesellino – at least 1 painting

- Pontormo (Jacopo da Pontormo) – at least 1 painting

- Raphael – at least 8 paintings, as well as an extensive collection of drawings. There are seven full-size cartoons for the tapestries designed to hang in the Sistine Chapel. During the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Raphael attained the zenith of his reputation. Consequently, the Raphael Cartoons have become some of the most famous, and widely imitated, paintings in the world. Since 1865 they have been on loan from the Royal Collection to the V&A.[41]

- Guido Reni – at least 1 painting

- Sebastiano Ricci – at least 14 paintings

- Girolamo Romanino – at least 1 painting

- Giulio Romano – at least 6 paintings

- Andrea Sacchi – at least 130 drawings

- Francesco de' Rossi (Il Salviati) – at least 1 painting

- Andrea del Sarto – at least 2 paintings

- Girolamo Savoldo – at least 2 paintings

- Andrea Schiavone – at least 2 paintings

- Bernardo Strozzi – at least 1 painting

- Zanobi Strozzi – at least 1 painting

- Tintoretto – at least 5 paintings

- Titian (Tiziano Vecelli) – at least 4 paintings

- Alessandro Turchi – at least 4 paintings

- Perin del Vaga – at least 2 paintings

- Giorgio Vasari – at least 1 painting

- Palma Vecchio – at least 2 paintings

- Paolo Veronese – at least 3 paintings

- Antonio Verrio – at least 1 painting

- Francesco Zuccarelli – at least 27 paintings, together with 8 works collaborated with Antonio Visentini

- Federico Zuccari – at least 1 painting

Furniture

Numbering over 300 items, the Royal Collection holds one of the greatest and most important collections of French furniture ever assembled. The collection is noted for its encyclopedic range as well as counting the greatest cabinet-makers of the Ancien Régime.

- Joseph Baumhauer – Bas d'armoire, c. 1765–70

- Pierre-Antoine Bellangé – at least 13 items, including:

Deux paire de Pedestals, inset with porcelain plaques, c. 1820

Paire de pier table, c. 1823–1824 (The Blue Drawing Room, Buckingham Palace)

Paire de petit pier table, c. 1823–24 (The Blue Drawing Room, Buckingham Palace)

Side table, c. 1820

Paire de secretaire, c. 1827-28

Paire de cabinets, (see pietra dura section), c. 1820 - André-Charles Boulle – at least 13 items, including:

Armoire, c. 1700 (The Grand Corridor, Windsor Castle)

Armoire, c. 1700 (The Grand Corridor, Windsor Castle)

Cabinet (en première-partie), c. 1700 (The Grand Corridor, Windsor Castle)

Cabinet (en contre-partie), c. 1700 (The Grand Corridor, Windsor Castle)

Cabinet, (without stand, similar to ones in the State Hermitage Museum and the collections of the Duke of Buccleuch)

Paire de bas d'armoire, (The Grand Corridor, Windsor Castle)

Writing table, possibly delivered to Louis, the Grand Dauphin (1661–1711), c. 1680

Paire de torchère, c. 1700

Bureau Plat, c. 1710 (The Rubens Room, Windsor Castle)

Petit gaines, attributed to., early 18th century - Martin Carlin – at least 2 items:

Cabinet (commode à vantaux), (see pietra dura section), c. 1778

Cabinet, mounted with Sèvres plaques, c. 1783 - Jacob-Desmalter & Cie – at least 1 item:

Bureau à cylindre, c. 1825 - Jacob Frères – at least 1 item:

Writing-table, c. 1805 - Gérard-Jean Galle – at least 1 item:

Candelabra x2, early 19th century - Pierre Garnier – at least 2 items:

Paire de cabinets, c. 1770 - Georges Jacob – at least 30 items, including:

Petit sofa, c. 1790

Tête-à-tête, c. 1790

Fauteuil, c. 1790

Lit à la Polonaise, c. 1790

Small armchairs and settees, suite of 20, c. 1786

Armchairs x4, c. 1786 - Gilles Joubert – at least 2 items:

Pair of Pedestals, delivered for the bedroom of Louis XV at Versailles, c. 1762 - Pierre Langlois – at least 5 items, including:

Commode, c. 1765 Deux paire de commode, c. 1763 - Étienne Levasseur – at least 7 items:

Side-table, attributed to, c. 1770 Deux paire de gaines, attributed to, c. 1770 Deux secretaire, adapted from an Andre-Charles Boulle table en bureau, c. 1770 - Martin-Eloy Lignereux – at least 2 items:

Paire de cabinets, (see pietra dura section), c. 1803 - Bernard Molitor – at least 3 items:

Commode, c. 1780

Paire de secretaires, c. 1815 - Bernard II van Risamburgh – at least 2 items:

Centre-table, c. 1775

Commode, c. 1745 - Jean Henri Riesener – at least 6 items:

Commode, delivered to Louis XVI's "Chambre du Roi" at Versailles, c. 1774;

Paire de encoignure, delivered to Louis XVI's "Chambre du Roi" at Versailles, c. 1774;

Jewel-cabinet, delivered to the Comtesse de Provence, c. 1787

Writing-table, c. 1785

Bureau à cylindre, c. 1775 - Sèvres – at least 1 item:

Centre-table, 'The Table of the Grand Commanders', c. 1806–12 (The Blue Drawing Room, Buckingham Palace) - Pierre-Philippe Thomire – at least 15 items, including:

Pedestal, c. 1813

Pedestal for the equestrian statue of Louis XIV, c. 1826

Paire de candelabra, 8 light, c. 1828

Torchères x11, c. 1814

Clock, mounts attributed to., 1803

Candelabra x2, early 19th century - Benjamin Vulliamy & Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy – at least 4 items:

Torchere x4, 1814 - Benjamin Vulliamy – at least 3 items:

Candelabra x2, 1811

Mantel clock, c. 1780 - Adam Weisweiler – at least 13 items:

Cabinet, inset with a Sèvres plaque, late 18th century

Cabinet, (see pietra dura section), 1780

Side Table, (see pietra dura section), c. 1780

Side Table, (see pietra dura section), c. 1785 (The Green Drawing Room, Buckingham Palace)

Paire de pier-table, in chinoiserie style, c. 1787–1790

Commode, c. 1785

Console-table x4, c.1785

Paire de petit bas d'armoire, manner of. boulle, late 18th century

- Robert Hume (English) – at least 1 item:

Pair of cabinets, (see pietra dura section), c. 1820 - Unknown (Flemish) – at least 2 items:

Cabinet-on-stand, c. 1660

Cabinet-on-stand, 17th century - Johann Daniel Sommer (German) – at least 2 items:

Pair of cabinets-on-stand, attributed to. (stands English), late 17th century - Melchior Baumgartner (German) – at least 2 items:

Organ Clock, 1664

Cabinet, (see Pietra Dura section), c. 1660 - Unknown (Dutch) – at least 1 item:

Secretaire-cabinet, in boulle marquetry, c. 1700 - Pietra Dura – at least 11 items:

Cabinet, Augsburg, attributed to Melchior Baumgartner, c. 1660

Cabinet, Italian, c. 1680

Cabinet, Adam Weisweiler – at least inset with pietra dura panels, 1780 (The Green Drawing Room, Buckingham Palace)

Side Table, Adam Weisweiler – at least inset with pietra dura panels, c. 1780 (The Silk Tapestry Room, Buckingham Palace)

Cabinet (commode à vantaux), Martin Carlin – at least inset with pietra dura panels re-used from Louis XIVs great Florentine cabinets, c. 1778 (The Silk Tapestry Room, Buckingham Palace)

Casket, Italian: Florentine, c. 1720

Paire de cabinets, Martin-Eloy Lignereux – at least inset with Florentine plaques, c. 1803

- Paire de cabinets, Pierre-Antoine Bellangé – at least inset with precious stones based on a Florentine design by Baccio del Bianco, c. 1820

- Paire de cabinets, Pierre-Antoine Bellangé – at least inset with precious stones based on a Florentine design by Baccio del Bianco, c. 1820

Pair of cabinets, Robert Hume, c. 1820 (The Crimson Drawing Room, Windsor Castle)

Four Florentine pietra dura panels on 18th century cabinets, re-adapted, c. 1820s (The White Drawing Room, Buckingham Palace) - Miscellaneous:

Cabinet-on-stand, magnificent example composed of ebony, mid-17th century

Bureau, magnificent example similar to a version in both the V&A and the Getty Museum, 1690–95

Bureaux Mazarin x2, in Boulle style, late 17th century

Bureaux Mazarin x2, in Boulle style, c. 1700 (The Ballroom, Windsor Castle)

Bureaux Mazarin, late 17th century (The West Gallery, Buckingham Palace)

Deux paire de boulle bas d'cabinets

Sculpture and decorative arts

- André-Charles Boulle – at least 4 items:

Mantle clock, c. 1710 (The Green Drawing Room, Windsor Castle)

Pedestal clock, (Similar to ones in Blenheim Palace, Chateau de Versailles, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Frick Collection and the Cleveland Museum of Art)

Pedestal clock, late 17th century;

Pedestal clock, c. 1720 - Abraham-Louis Breguet – at least 1 item:

Empire regulator clock, 1825 - De La Croix – at least 1 item:

Large clock, raised on a bronze plaque plinth, c. 1775 (The East Gallery, Buckingham Palace) - Gérard-Jean Galle – at least 1 item:

Clock, figures and frieze representing the Oath of the Horaatii, early 19th century - Jean-Pierre Latz – at least 2 items:

Pedestal Clock, (reputed from the Chateau de Versailles), c. 1735–40

Barometer and Pedestal, c. 1735 - Jean Antoine Lépine – at least 1 item:

Clock, in the form of an African Diana, the goddess of the Hunt, 1790 (The Blue Drawing Room, Buckingham Palace)

Astronomical Clock, c. 1790 (The Blue Drawing Room, Buckingham Palace) - Martin-Eloy Lignereux – at least 1 item:

Clock, 1803 - Pierre-Philippe Thomire – at least 1 item:

Clock, in the form of Apollo's chariot, c. 1805 (The State Dining Room, Buckingham Palace) - Benjamin Vulliamy – at least 1 item:

Clock, in the form of a bull, c. 1755–1760 - Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy – at least 1 item:

Clock, fitted with three porcelain figures, c. 1788 (The State Dining Room, Buckingham Palace)

- Matthew Boulton – at least 4 items:

Two pairs of vases, c. late 18th century (The Marble Hall, Buckingham Palace) - Fabergé – at least 3 Imperial Eggs and 1 Easter Egg

- Gérard-Jean Galle – at least 2 items:

Candelabra x2, in the form of cornucopias, c. early 19th century - François Rémond – at least 12 items:

Candelabra x8, 4 pairs, c. 1787 (The Blue Drawing Room & The Music Room, Buckingham Palace)

Candelabra x4, delivered to the comte d'Artois for the cabinet turc at Versailles, 1783 (The State Dining Room, Buckingham Palace) - Pierre-Philippe Thomire – at least 3 items:

Vase, c. early 19th century (The Music Room, Windsor Castle)

Candelabra x2, malachite and bronze, early 19th century (The White Drawing Room, Buckingham Palace)

Candelabra x2, malachite and bronze, c. 1828 (The State Dining Room, Buckingham Palace)

Candelabra x4, figures of patinated bronze, c. 1810 (The East Gallery, Buckingham Palace)

- Sèvres porcelain – Arguably the world's largest collection

- Chelsea porcelain – Complete service finished in 1763

- Antonio Canova – at least 3 items:

Mars and Venus, c. 1815–1817 (The Ministers' Staircase, Buckingham Palace)

Fountain nymph, 1819 (The Marble Hall, Buckingham Palace)

Dirce, 1824 (The Marble Hall, Buckingham Palace) - François Girardon – at least 1 item:

Bronze equestrian statue of Louis XIV, after Girardon, c. 1700 - Louis-Claude Vassé – at least 1 item:

Equestrian statue of Louis XV, a small reduction copy after the original by Edmé Bouchardon, c. 1764 - Antiquities – at least 2 items:

British Bronze Age - the Rillaton Gold Cup, on long-term loan to the British Museum.[42]

Lely Venus, a Hellenistic statue of the "crouching Venus" type, bought by Charles I, on long-term loan to the British Museum.

- The Story of Abraham, set of 10, woven in Brussels in the 1540s for Henry VIII

- Gobelins – at least 36 items:

Tapestry, four (from a series of twenty-eight designs) from the 'History of Don Quixote' given by Louis XVI to Richard Cosway, by whom presented to George IV, c. 1788

Tapestry, eight from the series 'Les Portières des Dieux', c. 18th century

Tapestry, four from the series 'Les Amours des Dieux', c. late 18th century

Tapestry, eight from the series 'Jason and the Golden Fleece', 1776-1779

Tapestry, seven from the series 'History of Esther', 1783

Tapestry, three from the series 'Story of Daphnis and Chloë', 1754

Tapestry, two from the series 'Story of Meleager and Atalanta', 1844

Costume

The collection has a number of items of clothing, including those worn by members of the Royal family, especially female members, some going back to the early 19th century. These include ceremonial dress and several wedding dresses, including that of Queen Victoria (1840).[43] There are also servant's livery uniforms, and a number of exotic pieces presented over the years, going back to a "war coat" of Tipu Sultan (d. 1799).[44] In recent years these have featured more prominently in displays and exhibitions, and are popular with the public.

Gems and Jewels

A collection of 277 cameos, intaglios, badges of insignia, snuffboxes and pieces of jewellery known as the Gems and Jewels are kept at Windsor Castle. Separate from Elizabeth II's jewels and the Crown Jewels, 24 pre-date the Renaissance and the rest were made in the 16th–19th centuries. In 1862, it was first shown publicly at the South Kensington Museum, now the Victoria and Albert Museum. Several objects were removed and others added in the second half of the Victorian period. An inventory of the collection was made in 1872, and a catalogue, Ancient and Modern Gems and Jewels in the Collection of Her Majesty The Queen, was published in 2008 by the Royal Collection Trust.[45]

Ownership

The Royal Collection is privately owned, although some of the works are displayed in areas of palaces and other royal residences open to visitors for the public to enjoy.[46] Some of the collection is owned by the monarch personally,[47] and everything else is described as being held in trust by the monarch in right of the Crown. It is understood that works of art acquired by monarchs up to the death of Queen Victoria in 1901 are heirlooms which fall into the latter category. Items the British royal family acquired later, including official gifts,[48] can be added to that part of the collection by a monarch at his or her discretion. Ambiguity surrounds the status of objects that have come into the possession of Elizabeth II during her reign.[49] The Royal Collection Trust has confirmed that all pieces left to the Queen by the Queen Mother, which include works by Monet, Nash, and Fabergé, belong to her personally.[50] It has also been confirmed that she owns the Royal stamp collection, inherited from her father George VI, as a private individual.[51]

Non-personal items are said to be inalienable as they can only be willed to the monarch's successor. The legal accuracy of this claim has never been substantiated in court.[52] According to Cameron Cobbold, then Lord Chamberlain, speaking in 1971, minor items have occasionally been sold to help raise money for acquisitions, and duplicates of items are given away as presents within the Commonwealth.[49] In 1995, Iain Sproat, then Secretary of State for National Heritage, told the House of Commons that selling objects was "entirely a matter for the Queen".[53] In a 2000 television interview, the Duke of Edinburgh said that the Queen was "technically, perfectly at liberty to sell them".[33]

Hypothetical questions have been asked in Parliament about what should happen to the collection if the UK ever becomes a republic.[54] In other European countries, the art collections of deposed monarchies usually have been taken into state ownership or become part of other national collections held in trust for the public's enjoyment.[55] Under the European Convention on Human Rights, incorporated into British law in 1998, the monarch may have to be compensated for the loss of any assets held in right of the Crown unless he or she agreed to surrender them voluntarily.[56]

Management

A registered charity, the Royal Collection Trust was set up in 1993 after the Windsor Castle fire with a mandate to conserve the works and enhance the public's appreciation and understanding of art.[57] It employs around 500 staff and is one of the five departments of the Royal Household.[58] Buildings do not come under its remit. In 2012, the team of curatorial staff numbered 29, and there were 32 conservationists.[59] Income is raised by charging entrance fees to see the collection at various locations and selling books and merchandise to the public. The Trust is financially independent and receives no Government funding or public subsidy.[60] A studio at Marlborough House is responsible for the conservation of furniture and decorative objects.[61]

The Royal Collection Trust is a company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales, No. 2713536. It is a Registered Charity No. 1016972; Registered Office: York House, St James's Palace, London SW1A 1BQ.

On its website, the Trust lists its purpose as overseeing the "maintenance and conservation of the Royal Collection, subject to proper custodial control in the service of the Queen and the nation." It also deals with acquisitions for the Royal Collection, and the display of the Royal Collection to the public.

The Board of Trustees includes the following officers of the Royal Household: the Lord Chamberlain, the Private Secretary to the Sovereign and the Keeper of the Privy Purse. Other Trustees are appointed for their knowledge and expertise in areas relevant to the charity's activities. Currently, the trustees are:

- Charles, Prince of Wales (Chairman)

- The Earl Peel (Deputy Chairman)

- The Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry

- Mr. Marc Bolland

- Vice Admiral Tony Johnstone-Burt (Master of the Household)

- Dr. Anna Keay

- The Hon. Sir James Leigh-Pemberton

- The Rt. Hon. Edward Young (Private Secretary)

- Sir Michael Stevens (Keeper of the Privy Purse and Treasurer to The Queen)

Gallery

.jpg.webp)

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Apollo and Diana, c. 1526

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Apollo and Diana, c. 1526_-_Sir_Henry_Guildford.jpg.webp) Hans Holbein the Younger, Portrait of Sir Henry Guildford, 1527

Hans Holbein the Younger, Portrait of Sir Henry Guildford, 1527 Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Massacre of the Innocents, 1565–1567

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Massacre of the Innocents, 1565–1567 Isaac Oliver, Young Man Seated under a Tree (portrait miniature), c. 1590–1596

Isaac Oliver, Young Man Seated under a Tree (portrait miniature), c. 1590–1596_-_The_Calling_of_Saints_Peter_and_Andrew_-_RCIN_402824_-_Hampton_Court_Palace.jpg.webp) Caravaggio, The Calling of Saints Peter and Andrew, c. 1602–1604

Caravaggio, The Calling of Saints Peter and Andrew, c. 1602–1604 Peter Paul Rubens, Milkmaids with cattle in a landscape, 'The Farm at Laken', c. 1617–1618

Peter Paul Rubens, Milkmaids with cattle in a landscape, 'The Farm at Laken', c. 1617–1618 Peter Paul Rubens, Self-Portrait, 1623

Peter Paul Rubens, Self-Portrait, 1623.jpg.webp) Frans Hals, Portrait of a Man, 1630

Frans Hals, Portrait of a Man, 1630 Orazio Gentileschi, Joseph and Potiphar's Wife, c. 1630–1632

Orazio Gentileschi, Joseph and Potiphar's Wife, c. 1630–1632_with_M._de_St_Antoine_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

_and_his_Wife%252C_Griet_Jans_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Rembrandt, The Shipbuilder and his Wife, 1633 (Jan Rijcksen (1560/2–1637) and his wife, Griet Jans)

Rembrandt, The Shipbuilder and his Wife, 1633 (Jan Rijcksen (1560/2–1637) and his wife, Griet Jans)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Anthony Van Dyck, Charles I in Three Positions, c. 1635–1636

Anthony Van Dyck, Charles I in Three Positions, c. 1635–1636_-_Artemisia_Gentileschi.jpg.webp) Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting, c. 1638–1639

Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting, c. 1638–1639.jpg.webp)

Canaletto, The Bacino di San Marco on Ascension Day, c. 1733–1734

Canaletto, The Bacino di San Marco on Ascension Day, c. 1733–1734 Thomas Gainsborough, Queen Charlotte, 1781

Thomas Gainsborough, Queen Charlotte, 1781

See also

References

- "The Adoration of the Kings". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 406767.

- "Venus and Adonis Embracing". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 406050.

- "The Flood". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 406106.

- "Diligence". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 402941.

- "Charles I with M. de St Antoine". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 404552.

- "Fame". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 402942.

- Stuart Jeffries (21 November 2002). "Kindness of strangers". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- Jerry Brotton (2 April 2006). "The great British art swindle". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016.

Some people know that this is perhaps the finest, and certainly what the royal palaces website proudly calls "the largest private collection of art in the world".

- "FAQs about the Royal Collection". Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016.

- "Jeremy, Curator of Prints and Drawings", RC website

- "Secrets of the Queen's paintings". The Telegraph. 15 February 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- "About the Collection: Photographs". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- Michael Prodger (22 January 2018). "The cavalier collector: how Charles I gained (and lost) some of the world's best art". New Statesman. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- Michael Prodger (17 December 2017). "The Royals' Treasures". Culture. The Sunday Times. pp. 44–45.

- "Lady at the Virginals with a Gentleman". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 405346.

- Lloyd (1991), 143, 164, 166

- "George III", Royal Collection

- "King George IV", Royal Collection; Lloyd (1991), 143

- "The King's Library, British Library

- "Royal manuscripts", British Library

- R. Brinley Jones, ‘Llwyd, Humphrey (1527–1568)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004

- "Prince Albert and the Gallery", National Gallery

- Sir Hugh Roberts in Roberts, pp. 25 and 391.

- Jackson, p. 59.

- Hall, p. 660.

- "The Triumphs of Caesar: 4. The Vase-Bearers". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 403961.

- "Portrait of Jacopo Sannazaro". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 407190.

- "Works of Art". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 216. United Kingdom: House of Commons. 11 January 1993. col. 540W.

- "Royal Collection". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 315. United Kingdom: House of Commons. 7 July 1998. col. 429W.

- Hardman, p. 102.

- "Explore the Collection", Royal Collection, accessed 1 October 2020

- "Art Collections". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 219. United Kingdom: House of Commons. 19 February 1993. col. 366W.

- "The convenient fiction of who owns priceless treasure". The Guardian. 30 May 2002. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- Clayton and Whitaker, pp. 12 and 16.

- "Drawings, Watercolours, and Prints". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- "LEONARDO DA VINCI: A LIFE IN DRAWING". RCT. 8 February 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

A nationwide celebration during 2019

- "Leonardo da Vinci's Artistic Brilliance Endures 500 Years After His Death". National Geographic. 1 May 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- The Social Affairs Unit – at least Web Review: Dutch Paintings at the Royal Collection

- "Giuseppe Macpherson (1726-C. 1780) – Guercino (1591-1666)". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Jones, Jonathan (30 August 2006). "The real Da Vinci code". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- "The story of the Raphael Cartoons". V&A. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- "Rillaton Cup", Royal Collection

- "Queen Victoria's wedding dress, 1840", Royal Collection

- "War coat of Tipu Sultan, 1785-90", Royal Collection

- Piacenti and Boardman, p. 11.

- Lloyd, p. 11. "It is, therefore, a private collection, although its sheer size (some 7,000 pictures) and its display in palaces and royal residences (several of which are open to the public) give it a public dimension".

- "Royal Taxation". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 351. United Kingdom: House of Commons. 7 June 2000. col. 273W.

There is a computerised inventory of the Royal Collection which identifies assets held by the Queen as Sovereign and as a private individual.

- "Force the Royal Family to declare gifts, say MPs". Evening Standard. London. 30 January 2007. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- Morton, p. 156.

- McClure, pp. 209–210.

- McClure, p. 20.

- Paxman, p. 165.

- "Ethiopian Manuscripts". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 263. United Kingdom: House of Commons. 19 July 1995. col. 1463W.

- "Royal Finances". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 388. United Kingdom: House of Commons. 9 July 2002. col. 221WH.

- Lloyd, p. 12.

- Cahill, p. 77.

- Hardman, p. 43.

- "Working for us". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- "The Royal Collection: Not only for Queen, but also for country". The Telegraph. 28 May 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- "Full accounts made up to 31 March 2015". Companies House. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- "Annual report 2006/7" (PDF). Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2016.

Bibliography

- Cahill, Kevin (2001). Who owns Britain. Canongate. ISBN 978-0-86241-912-7.

- Clayton, Martin; Whitaker, Lucy (2007). The Art of Italy in the Royal Collection: Renaissance & Baroque. Royal Collection Trust. ISBN 978-1-902163-29-1.

- Hall, Michael (2017). Art, Passion & Power: The Story of the Royal Collection. BBC Books. ISBN 978-1-785-94261-7.

- Hardman, Robert (2011). Our Queen. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4070-8808-2.

- Jackson, D. Michael (2018). The Canadian Kingdom: 150 Years of Constitutional Monarchy. Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-4597-4119-5.

- Lloyd, Christopher (1991), The Queen's Pictures, Royal Collectors through the centuries, National Gallery Publications, ISBN 0947645896

- Lloyd, Christopher (1999). The Paintings in the Royal Collection: A Thematic Exploration. Royal Collection Enterprises. ISBN 978-1-902163-59-8.

- McClure, David (2015). Royal Legacy. Thistle. ISBN 978-1910198650.

- Morton, Andrew (1989). Theirs Is the Kingdom: The Wealth of the Windsors. Michael O'Mara Books. ISBN 978-0-948397-23-3.

- Paxman, Jeremy (2007). On Royalty. Penguin Adult. ISBN 978-0-14-101222-3.

- Piacenti, Kirsten Aschengreen; Boardman, John (2008). Ancient and Modern Gems and Jewels in the Collection of Her Majesty The Queen (PDF). Royal Collection Trust. ISBN 978-1-902163-47-5.

- Roberts, Jane, ed. (2002). Royal Treasures: A Golden Jubilee Celebration. Royal Collection Trust. ISBN 978-1-9021-6349-9.

Further reading

- Bird, Rufus; Clayton, Martin, eds. (2018). Charles II: Art & Power. Royal Collection Trust. ISBN 978-1-909741-44-7.

- Cornforth, John (1996). Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother at Clarence House. Michael Joseph. ISBN 978-0-7181-4191-2.

- MacGregor, Arthur, ed. (1989). The Late King's Goods. Alistair McAlpine. ISBN 978-0-19-920171-6.

- Millar, Oliver (1977). The Queen's Pictures. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-77267-5.

- Parissien, Steven (2001). George IV: The Grand Entertainment. John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5652-4.

- Plumb, J. H.; Wheldon, Huw (1977). Royal Heritage: The Story of Britain's Royal Builders and Collectors. BBC Books. ISBN 978-0-563-17082-2.

- Roberts, Jane, ed. (2004). George III and Queen Charlotte: Patronage, Collecting and Court Taste. Royal Collection Trust. ISBN 978-1-9021-6373-4.

- Roberts, Jane (2008). Treasures: The Royal Collection. Royal Collection Trust. ISBN 978-1-905-68606-3.

- Rumberg, Per; Shawe-Taylor, Desmond, eds. (2017). Charles I: King and Collector. Royal Academy of Arts. ISBN 978-1-910350-67-6.

- Shawe-Taylor, Desmond, ed. (2014). The First Georgians: Art & Monarchy, 1714–1760. Royal Collection Trust. ISBN 978-1-905686-79-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to the Royal Collection. |

- Royal Collection Trust – official website

- Royal Collection Trust channel at Vimeo

- Podcast library at iTunes (free)