Piezoelectricity

Piezoelectricity is the electric charge that accumulates in certain solid materials (such as crystals, certain ceramics, and biological matter such as bone, DNA and various proteins)[1] in response to applied mechanical stress. The word piezoelectricity means electricity resulting from pressure and latent heat. It is derived from the Greek word πιέζειν; piezein, which means to squeeze or press, and ἤλεκτρον ēlektron, which means amber, an ancient source of electric charge.[2][3] French physicists Jacques and Pierre Curie discovered piezoelectricity in 1880.[4]

The piezoelectric effect results from the linear electromechanical interaction between the mechanical and electrical states in crystalline materials with no inversion symmetry.[5] The piezoelectric effect is a reversible process: materials exhibiting the piezoelectric effect (the internal generation of electrical charge resulting from an applied mechanical force) also exhibit the reverse piezoelectric effect, the internal generation of a mechanical strain resulting from an applied electrical field. For example, lead zirconate titanate crystals will generate measurable piezoelectricity when their static structure is deformed by about 0.1% of the original dimension. Conversely, those same crystals will change about 0.1% of their static dimension when an external electric field is applied to the material. The inverse piezoelectric effect is used in the production of ultrasonic sound waves.[6]

Piezoelectricity is exploited in a number of useful applications, such as the production and detection of sound, piezoelectric inkjet printing, generation of high voltages, clock generator in electronics, microbalances, to drive an ultrasonic nozzle, and ultrafine focusing of optical assemblies. It forms the basis for a number of scientific instrumental techniques with atomic resolution, the scanning probe microscopies, such as STM, AFM, MTA, and SNOM. It also finds everyday uses such as acting as the ignition source for cigarette lighters, push-start propane barbecues, used as the time reference source in quartz watches, as well as in amplification pickups for some guitars and triggers in most modern electronic drums.[7][8]

History

Discovery and early research

The pyroelectric effect, by which a material generates an electric potential in response to a temperature change, was studied by Carl Linnaeus and Franz Aepinus in the mid-18th century. Drawing on this knowledge, both René Just Haüy and Antoine César Becquerel posited a relationship between mechanical stress and electric charge; however, experiments by both proved inconclusive.[9]

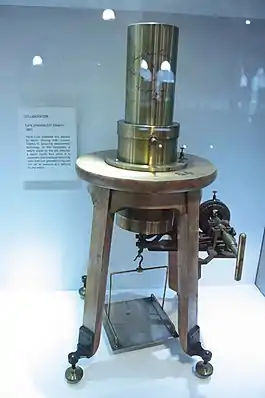

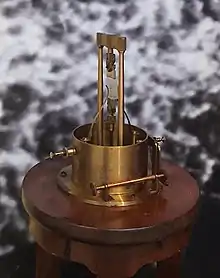

The first demonstration of the direct piezoelectric effect was in 1880 by the brothers Pierre Curie and Jacques Curie.[10] They combined their knowledge of pyroelectricity with their understanding of the underlying crystal structures that gave rise to pyroelectricity to predict crystal behavior, and demonstrated the effect using crystals of tourmaline, quartz, topaz, cane sugar, and Rochelle salt (sodium potassium tartrate tetrahydrate). Quartz and Rochelle salt exhibited the most piezoelectricity.

The Curies, however, did not predict the converse piezoelectric effect. The converse effect was mathematically deduced from fundamental thermodynamic principles by Gabriel Lippmann in 1881.[11] The Curies immediately confirmed the existence of the converse effect,[12] and went on to obtain quantitative proof of the complete reversibility of electro-elasto-mechanical deformations in piezoelectric crystals.

For the next few decades, piezoelectricity remained something of a laboratory curiosity, though it was a vital tool in the discovery of polonium and radium by Pierre and Marie Curie in 1898. More work was done to explore and define the crystal structures that exhibited piezoelectricity. This culminated in 1910 with the publication of Woldemar Voigt's Lehrbuch der Kristallphysik (Textbook on Crystal Physics),[13] which described the 20 natural crystal classes capable of piezoelectricity, and rigorously defined the piezoelectric constants using tensor analysis.

World War I and post-war

The first practical application for piezoelectric devices was sonar, first developed during World War I. In France in 1917, Paul Langevin and his coworkers developed an ultrasonic submarine detector.[14] The detector consisted of a transducer, made of thin quartz crystals carefully glued between two steel plates, and a hydrophone to detect the returned echo. By emitting a high-frequency pulse from the transducer, and measuring the amount of time it takes to hear an echo from the sound waves bouncing off an object, one can calculate the distance to that object.

The use of piezoelectricity in sonar, and the success of that project, created intense development interest in piezoelectric devices. Over the next few decades, new piezoelectric materials and new applications for those materials were explored and developed.

Piezoelectric devices found homes in many fields. Ceramic phonograph cartridges simplified player design, were cheap and accurate, and made record players cheaper to maintain and easier to build. The development of the ultrasonic transducer allowed for easy measurement of viscosity and elasticity in fluids and solids, resulting in huge advances in materials research. Ultrasonic time-domain reflectometers (which send an ultrasonic pulse through a material and measure reflections from discontinuities) could find flaws inside cast metal and stone objects, improving structural safety.

World War II and post-war

During World War II, independent research groups in the United States, Russia, and Japan discovered a new class of synthetic materials, called ferroelectrics, which exhibited piezoelectric constants many times higher than natural materials. This led to intense research to develop barium titanate and later lead zirconate titanate materials with specific properties for particular applications.

One significant example of the use of piezoelectric crystals was developed by Bell Telephone Laboratories. Following World War I, Frederick R. Lack, working in radio telephony in the engineering department, developed the "AT cut" crystal, a crystal that operated through a wide range of temperatures. Lack's crystal did not need the heavy accessories previous crystal used, facilitating its use on aircraft. This development allowed Allied air forces to engage in coordinated mass attacks through the use of aviation radio.

Development of piezoelectric devices and materials in the United States was kept within the companies doing the development, mostly due to the wartime beginnings of the field, and in the interests of securing profitable patents. New materials were the first to be developed—quartz crystals were the first commercially exploited piezoelectric material, but scientists searched for higher-performance materials. Despite the advances in materials and the maturation of manufacturing processes, the United States market did not grow as quickly as Japan's did. Without many new applications, the growth of the United States' piezoelectric industry suffered.

In contrast, Japanese manufacturers shared their information, quickly overcoming technical and manufacturing challenges and creating new markets. In Japan, a temperature stable crystal cut was developed by Issac Koga. Japanese efforts in materials research created piezoceramic materials competitive to the United States materials but free of expensive patent restrictions. Major Japanese piezoelectric developments included new designs of piezoceramic filters for radios and televisions, piezo buzzers and audio transducers that can connect directly to electronic circuits, and the piezoelectric igniter, which generates sparks for small engine ignition systems and gas-grill lighters, by compressing a ceramic disc. Ultrasonic transducers that transmit sound waves through air had existed for quite some time but first saw major commercial use in early television remote controls. These transducers now are mounted on several car models as an echolocation device, helping the driver determine the distance from the car to any objects that may be in its path.

Mechanism

The nature of the piezoelectric effect is closely related to the occurrence of electric dipole moments in solids. The latter may either be induced for ions on crystal lattice sites with asymmetric charge surroundings (as in BaTiO3 and PZTs) or may directly be carried by molecular groups (as in cane sugar). The dipole density or polarization (dimensionality [C·m/m3] ) may easily be calculated for crystals by summing up the dipole moments per volume of the crystallographic unit cell.[15] As every dipole is a vector, the dipole density P is a vector field. Dipoles near each other tend to be aligned in regions called Weiss domains. The domains are usually randomly oriented, but can be aligned using the process of poling (not the same as magnetic poling), a process by which a strong electric field is applied across the material, usually at elevated temperatures. Not all piezoelectric materials can be poled.[16]

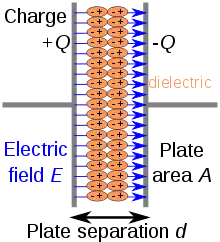

Of decisive importance for the piezoelectric effect is the change of polarization P when applying a mechanical stress. This might either be caused by a reconfiguration of the dipole-inducing surrounding or by re-orientation of molecular dipole moments under the influence of the external stress. Piezoelectricity may then manifest in a variation of the polarization strength, its direction or both, with the details depending on: 1. the orientation of P within the crystal; 2. crystal symmetry; and 3. the applied mechanical stress. The change in P appears as a variation of surface charge density upon the crystal faces, i.e. as a variation of the electric field extending between the faces caused by a change in dipole density in the bulk. For example, a 1 cm3 cube of quartz with 2 kN (500 lbf) of correctly applied force can produce a voltage of 12500 V.[17]

Piezoelectric materials also show the opposite effect, called the converse piezoelectric effect, where the application of an electrical field creates mechanical deformation in the crystal.

Mathematical description

Linear piezoelectricity is the combined effect of

- The linear electrical behavior of the material:

- where D is the electric flux density[18][19] (electric displacement), ε is the permittivity (free-body dielectric constant), E is the electric field strength, and .

- Hooke's law for linear elastic materials:

- where S is the linearized strain, s is compliance under short-circuit conditions, T is stress, and

- ,

- where u is the displacement vector.

These may be combined into so-called coupled equations, of which the strain-charge form is:[20]

where is the piezoelectric tensor and the superscript t stands for its transpose. Due to the symmetry of , .

In matrix form,

where [d] is the matrix for the direct piezoelectric effect and [dt] is the matrix for the converse piezoelectric effect. The superscript E indicates a zero, or constant, electric field; the superscript T indicates a zero, or constant, stress field; and the superscript t stands for transposition of a matrix.

Notice that the third order tensor maps vectors into symmetric matrices. There are no non-trivial rotation-invariant tensors that have this property, which is why there are no isotropic piezoelectric materials.

The strain-charge for a material of the 4mm (C4v) crystal class (such as a poled piezoelectric ceramic such as tetragonal PZT or BaTiO3) as well as the 6mm crystal class may also be written as (ANSI IEEE 176):

where the first equation represents the relationship for the converse piezoelectric effect and the latter for the direct piezoelectric effect.[21]

Although the above equations are the most used form in literature, some comments about the notation are necessary. Generally, D and E are vectors, that is, Cartesian tensors of rank 1; and permittivity ε is a Cartesian tensor of rank 2. Strain and stress are, in principle, also rank-2 tensors. But conventionally, because strain and stress are all symmetric tensors, the subscript of strain and stress can be relabeled in the following fashion: 11 → 1; 22 → 2; 33 → 3; 23 → 4; 13 → 5; 12 → 6. (Different conventions may be used by different authors in literature. For example, some use 12 → 4; 23 → 5; 31 → 6 instead.) That is why S and T appear to have the "vector form" of six components. Consequently, s appears to be a 6-by-6 matrix instead of a rank-3 tensor. Such a relabeled notation is often called Voigt notation. Whether the shear strain components S4, S5, S6 are tensor components or engineering strains is another question. In the equation above, they must be engineering strains for the 6,6 coefficient of the compliance matrix to be written as shown, i.e., 2(sE

11 − sE

12). Engineering shear strains are double the value of the corresponding tensor shear, such as S6 = 2S12 and so on. This also means that s66 = 1/G12, where G12 is the shear modulus.

In total, there are four piezoelectric coefficients, dij, eij, gij, and hij defined as follows:

where the first set of four terms corresponds to the direct piezoelectric effect and the second set of four terms corresponds to the converse piezoelectric effect. The equality between the direct piezoelectric tensor and the transpose of the converse piezoelectric tensor originates from the Maxwell relations of thermodynamics.[22] For those piezoelectric crystals for which the polarization is of the crystal-field induced type, a formalism has been worked out that allows for the calculation of piezoelectrical coefficients dij from electrostatic lattice constants or higher-order Madelung constants.[15]

Crystal classes

Of the 32 crystal classes, 21 are non-centrosymmetric (not having a centre of symmetry), and of these, 20 exhibit direct piezoelectricity[23] (the 21st is the cubic class 432). Ten of these represent the polar crystal classes,[24] which show a spontaneous polarization without mechanical stress due to a non-vanishing electric dipole moment associated with their unit cell, and which exhibit pyroelectricity. If the dipole moment can be reversed by applying an external electric field, the material is said to be ferroelectric.

- The 10 polar (pyroelectric) crystal classes: 1, 2, m, mm2, 4, 4mm, 3, 3m, 6, 6mm.

- The other 10 piezoelectric crystal classes: 222, 4, 422, 42m, 32, 6, 622, 62m, 23, 43m.

For polar crystals, for which P ≠ 0 holds without applying a mechanical load, the piezoelectric effect manifests itself by changing the magnitude or the direction of P or both.

For the nonpolar but piezoelectric crystals, on the other hand, a polarization P different from zero is only elicited by applying a mechanical load. For them the stress can be imagined to transform the material from a nonpolar crystal class (P = 0) to a polar one,[15] having P ≠ 0.

Materials

Many materials exhibit piezoelectricity.

Crystalline materials

- Langasite (La3Ga5SiO14) – a quartz-analogous crystal

- Gallium orthophosphate (GaPO4) – a quartz-analogous crystal

- Lithium niobate (LiNbO3)

- Lithium tantalate (LiTaO3)

- Quartz

- Berlinite (AlPO4) – a rare phosphate mineral that is structurally identical to quartz

- Rochelle salt

- Topaz – Piezoelectricity in Topaz can probably be attributed to ordering of the (F,OH) in its lattice, which is otherwise centrosymmetric: orthorhombic bipyramidal (mmm). Topaz has anomalous optical properties which are attributed to such ordering.[25]

- Tourmaline-group minerals

- Lead titanate (PbTiO3) – Although it occurs in nature as mineral macedonite,[26][27] it is synthesized for research and applications.

Ceramics

Ceramics with randomly oriented grains must be ferroelectric to exhibit piezoelectricity.[28] The occurrence of abnormal grain growth (AGG) in sintered polycrystalline piezoelectric ceramics has detrimental effects on the piezoelectric performance in such systems and should be avoided, as the microstructure in piezoceramics exhibiting AGG tends to consist of few abnormally large elongated grains in a matrix of randomly oriented finer grains. Macroscopic piezoelectricity is possible in textured polycrystalline non-ferroelectric piezoelectric materials, such as AlN and ZnO. The families of ceramics with perovskite, tungsten-bronze, and related structures exhibit piezoelectricity:

- Lead zirconate titanate (Pb[ZrxTi1−x]O3 with 0 ≤ x ≤ 1) – more commonly known as PZT, the most common piezoelectric ceramic in use today.

- Potassium niobate (KNbO3)[29]

- Sodium tungstate (Na2WO3)

- Ba2NaNb5O5

- Pb2KNb5O15

- Zinc oxide (ZnO) – Wurtzite structure. While single crystals of ZnO are piezoelectric and pyroelectric, polycrystalline (ceramic) ZnO with randomly oriented grains exhibits neither piezoelectric nor pyroelectric effect. Not being ferroelectric, polycrystalline ZnO cannot be poled like barium titanate or PZT. Ceramics and polycrystalline thin films of ZnO may exhibit macroscopic piezoelectricity and pyroelectricity only if they are textured (grains are preferentially oriented), such that the piezoelectric and pyroelectric responses of all individual grains do not cancel. This is readily accomplished in polycrystalline thin films.[21]

Lead-free piezoceramics

- Sodium potassium niobate ((K,Na)NbO3). This material is also known as NKN or KNN. In 2004, a group of Japanese researchers led by Yasuyoshi Saito discovered a sodium potassium niobate composition with properties close to those of PZT, including a high TC.[30] Certain compositions of this material have been shown to retain a high mechanical quality factor (Qm ≈ 900) with increasing vibration levels, whereas the mechanical quality factor of hard PZT degrades in such conditions. This fact makes NKN a promising replacement for high power resonance applications, such as piezoelectric transformers.[31]

- Bismuth ferrite (BiFeO3) – a promising candidate for the replacement of lead-based ceramics.

- Sodium niobate (NaNbO3)

- Barium titanate (BaTiO3) – Barium titanate was the first piezoelectric ceramic discovered.

- Bismuth titanate (Bi4Ti3O12)

- Sodium bismuth titanate (NaBi(TiO3)2)

The fabrication of lead-free piezoceramics pose multiple challenges, from an environmental standpoint and their ability to replicate the properties of their lead-based counterparts. By removing the lead component of the piezoceramic, the risk of toxicity to humans decreases, but the mining and extraction of the materials can be harmful to the environment.[32] Analysis of the environmental profile of PZT versus sodium potassium niobate (NKN or KNN) shows that across the four indicators considered (primary energy consumption, toxicological footprint, eco-indicator 99, and input-output upstream greenhouse gas emissions), KNN is actually more harmful to the environment. Most of the concerns with KNN, specifically its Nb2O5 component, are in the early phase of its life cycle before it reaches manufacturers. Since the harmful impacts are focused on these early phases, some actions can be taken to minimize the effects. Returning the land as close to its original form after Nb2O5 mining via dam deconstruction or replacing a stockpile of utilizable soil are known aids for any extraction event. For minimizing air quality effects, modeling and simulation still needs to occur to fully understand what mitigation methods are required. The extraction of lead-free piezoceramic components has not grown to a significant scale at this time, but from early analysis, experts encourage caution when it comes to environmental effects.

Fabricating lead-free piezoceramics faces the challenge of maintaining the performance and stability of their lead-based counterparts. In general, the main fabrication challenge is creating the "morphotropic phase boundaries (MPBs)" that provide the materials with their stable piezoelectric properties without introducing the "polymorphic phase boundaries (PPBs)" that decrease the temperature stability of the material.[33] New phase boundaries are created by varying additive concentrations so that the phase transition temperatures converge at room temperature. The introduction of the MPB improves piezoelectric properties, but if a PPB is introduced, the material becomes negatively affected by temperature. Research is ongoing to control the type of phase boundaries that are introduced through phase engineering, diffusing phase transitions, domain engineering, and chemical modification.

III–V and II–VI semiconductors

A piezoelectric potential can be created in any bulk or nanostructured semiconductor crystal having non central symmetry, such as the Group III–V and II–VI materials, due to polarization of ions under applied stress and strain. This property is common to both the zincblende and wurtzite crystal structures. To first order, there is only one independent piezoelectric coefficient in zincblende, called e14, coupled to shear components of the strain. In wurtzite, there are instead three independent piezoelectric coefficients: e31, e33 and e15. The semiconductors where the strongest piezoelectricity is observed are those commonly found in the wurtzite structure, i.e. GaN, InN, AlN and ZnO (see piezotronics).

Since 2006, there have also been a number of reports of strong non linear piezoelectric effects in polar semiconductors.[34] Such effects are generally recognized to be at least important if not of the same order of magnitude as the first order approximation.

Polymers

The piezo-response of polymers is not as high as the response for ceramics; however, polymers hold properties that ceramics do not. Over the last few decades, non-toxic, piezoelectric polymers have been studied and applied due to their flexibility and smaller acoustical impedance.[35] Other properties that make these materials significant include their biocompatibility, biodegradability, low cost, and low power consumption compared to other piezo-materials (ceramics, etc.).[36] Piezoelectric polymers and non-toxic polymer composites can be used given their different physical properties.

Piezoelectric polymers can be classified by bulk polymers, voided charged polymers ("piezoelectrets"), and polymer composites. A piezo-response observed by bulk polymers is mostly due to its molecular structure. There are two types of bulk polymers: amorphous and semi-crystalline. Examples of semi-crystalline polymers are Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) and its copolymers, Polyamides, and Parylene-C. Non-crystalline polymers, such as Polyimide and Polyvinylidene Chloride (PVDC), fall under amorphous bulk polymers. Voided charged polymers exhibit the piezoelectric effect due to charge induced by poling of a porous polymeric film. Under an electric field, charges form on the surface of the voids forming dipoles. Electric responses can be caused by any deformation of these voids. The piezoelectric effect can also be observed in polymer composites by integrating piezoelectric ceramic particles into a polymer film. A polymer does not have to be piezo-active to be an effective material for a polymer composite.[36] In this case, a material could be made up of an inert matrix with a separate piezo-active component.

PVDF exhibits piezoelectricity several times greater than quartz. The piezo-response observed from PVDF is about 20–30 pC/N. That is an order of 5–50 times less than that of piezoelectric ceramic lead zirconate titanate (PZT).[35][36] The thermal stability of the piezoelectric effect of polymers in the PVDF family (i.e. vinylidene fluoride co-poly trifluoroethylene) goes up to 125 °C. Some applications of PVDF are pressure sensors, hydrophones, and shock wave sensors.[35]

Due to their flexibility, piezoelectric composites have been proposed as energy harvesters and nanogenerators. In 2018, it was reported by Zhu et al. that a piezoelectric response of about 17 pC/N could be obtained from PDMS/PZT nanocomposite at 60% porosity.[37] Another PDMS nanocomposite was reported in 2017, in which BaTiO3 was integrated into PDMS to make a stretchable, transparent nanogenerator for self-powered physiological monitoring.[38] In 2016, polar molecules were introduced into a polyurethane foam in which high responses of up to 244 pC/N were reported.[39]

Other materials

Most materials exhibit at least weak piezoelectric responses. Trivial examples include sucrose (table sugar), DNA, viral proteins, including those from bacteriophage.[40][41] An actuator based on wood fibers, called cellulose fibers, has been reported.[36] D33 responses for cellular polypropylene are around 200 pC/N. Some applications of cellular polypropylene are musical key pads, microphones, and ultrasound-based echolocation systems.[35] Recently, single amino acid such as β-glycine also displayed high piezoelectric (178 pmV−1) as compared to other biological materials.[42]

Application

Currently, industrial and manufacturing is the largest application market for piezoelectric devices, followed by the automotive industry. Strong demand also comes from medical instruments as well as information and telecommunications. The global demand for piezoelectric devices was valued at approximately US$14.8 billion in 2010. The largest material group for piezoelectric devices is piezoceramics, and piezopolymer is experiencing the fastest growth due to its low weight and small size.[43]

Piezoelectric crystals are now used in numerous ways:

High voltage and power sources

Direct piezoelectricity of some substances, like quartz, can generate potential differences of thousands of volts.

- The best-known application is the electric cigarette lighter: pressing the button causes a spring-loaded hammer to hit a piezoelectric crystal, producing a sufficiently high-voltage electric current that flows across a small spark gap, thus heating and igniting the gas. The portable sparkers used to ignite gas stoves work the same way, and many types of gas burners now have built-in piezo-based ignition systems.

- A similar idea is being researched by DARPA in the United States in a project called energy harvesting, which includes an attempt to power battlefield equipment by piezoelectric generators embedded in soldiers' boots. However, these energy harvesting sources by association affect the body. DARPA's effort to harness 1–2 watts from continuous shoe impact while walking were abandoned due to the impracticality and the discomfort from the additional energy expended by a person wearing the shoes. Other energy harvesting ideas include harvesting the energy from human movements in train stations or other public places[44][45] and converting a dance floor to generate electricity.[46] Vibrations from industrial machinery can also be harvested by piezoelectric materials to charge batteries for backup supplies or to power low-power microprocessors and wireless radios.[47]

- A piezoelectric transformer is a type of AC voltage multiplier. Unlike a conventional transformer, which uses magnetic coupling between input and output, the piezoelectric transformer uses acoustic coupling. An input voltage is applied across a short length of a bar of piezoceramic material such as PZT, creating an alternating stress in the bar by the inverse piezoelectric effect and causing the whole bar to vibrate. The vibration frequency is chosen to be the resonant frequency of the block, typically in the 100 kilohertz to 1 megahertz range. A higher output voltage is then generated across another section of the bar by the piezoelectric effect. Step-up ratios of more than 1,000:1 have been demonstrated. An extra feature of this transformer is that, by operating it above its resonant frequency, it can be made to appear as an inductive load, which is useful in circuits that require a controlled soft start.[48] These devices can be used in DC–AC inverters to drive cold cathode fluorescent lamps. Piezo transformers are some of the most compact high voltage sources.

Sensors

The principle of operation of a piezoelectric sensor is that a physical dimension, transformed into a force, acts on two opposing faces of the sensing element. Depending on the design of a sensor, different "modes" to load the piezoelectric element can be used: longitudinal, transversal and shear.

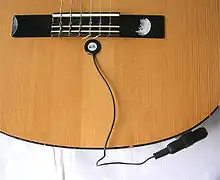

Detection of pressure variations in the form of sound is the most common sensor application, e.g. piezoelectric microphones (sound waves bend the piezoelectric material, creating a changing voltage) and piezoelectric pickups for acoustic-electric guitars. A piezo sensor attached to the body of an instrument is known as a contact microphone.

Piezoelectric sensors especially are used with high frequency sound in ultrasonic transducers for medical imaging and also industrial nondestructive testing (NDT).

For many sensing techniques, the sensor can act as both a sensor and an actuator—often the term transducer is preferred when the device acts in this dual capacity, but most piezo devices have this property of reversibility whether it is used or not. Ultrasonic transducers, for example, can inject ultrasound waves into the body, receive the returned wave, and convert it to an electrical signal (a voltage). Most medical ultrasound transducers are piezoelectric.

In addition to those mentioned above, various sensor applications include:

- Piezoelectric elements are also used in the detection and generation of sonar waves.

- Piezoelectric materials are used in single-axis and dual-axis tilt sensing.[50]

- Power monitoring in high power applications (e.g. medical treatment, sonochemistry and industrial processing).

- Piezoelectric microbalances are used as very sensitive chemical and biological sensors.

- Piezos are sometimes used in strain gauges.

- A piezoelectric transducer was used in the penetrometer instrument on the Huygens Probe.

- Piezoelectric transducers are used in electronic drum pads to detect the impact of the drummer's sticks, and to detect muscle movements in medical acceleromyography.

- Automotive engine management systems use piezoelectric transducers to detect Engine knock (Knock Sensor, KS), also known as detonation, at certain hertz frequencies. A piezoelectric transducer is also used in fuel injection systems to measure manifold absolute pressure (MAP sensor) to determine engine load, and ultimately the fuel injectors milliseconds of on time.

- Ultrasonic piezo sensors are used in the detection of acoustic emissions in acoustic emission testing.

- Piezoelectric transducers can be used in transit-time ultrasonic flow meters.

Actuators

As very high electric fields correspond to only tiny changes in the width of the crystal, this width can be changed with better-than-µm precision, making piezo crystals the most important tool for positioning objects with extreme accuracy—thus their use in actuators.[51] Multilayer ceramics, using layers thinner than 100 µm, allow reaching high electric fields with voltage lower than 150 V. These ceramics are used within two kinds of actuators: direct piezo actuators and amplified piezoelectric actuators. While direct actuator's stroke is generally lower than 100 µm, amplified piezo actuators can reach millimeter strokes.

- Loudspeakers: Voltage is converted to mechanical movement of a metallic diaphragm.

- Piezoelectric motors: Piezoelectric elements apply a directional force to an axle, causing it to rotate. Due to the extremely small distances involved, the piezo motor is viewed as a high-precision replacement for the stepper motor.

- Piezoelectric elements can be used in laser mirror alignment, where their ability to move a large mass (the mirror mount) over microscopic distances is exploited to electronically align some laser mirrors. By precisely controlling the distance between mirrors, the laser electronics can accurately maintain optical conditions inside the laser cavity to optimize the beam output.

- A related application is the acousto-optic modulator, a device that scatters light off soundwaves in a crystal, generated by piezoelectric elements. This is useful for fine-tuning a laser's frequency.

- Atomic force microscopes and scanning tunneling microscopes employ converse piezoelectricity to keep the sensing needle close to the specimen.[52]

- Inkjet printers: On many inkjet printers, piezoelectric crystals are used to drive the ejection of ink from the inkjet print head towards the paper.

- Diesel engines: High-performance common rail diesel engines use piezoelectric fuel injectors, first developed by Robert Bosch GmbH, instead of the more common solenoid valve devices.

- Active vibration control using amplified actuators.

- X-ray shutters.

- XY stages for micro scanning used in infrared cameras.

- Moving the patient precisely inside active CT and MRI scanners where the strong radiation or magnetism precludes electric motors.[53]

- Crystal earpieces are sometimes used in old or low power radios.

- High-intensity focused ultrasound for localized heating or creating a localized cavitation can be achieved, for example, in patient's body or in an industrial chemical process.

- Refreshable braille display. A small crystal is expanded by applying a current that moves a lever to raise individual braille cells.

- Piezoelectric actuator. A single crystal or a number of crystals are expanded by applying a voltage for moving and controlling a mechanism or system.[51]

Frequency standard

The piezoelectrical properties of quartz are useful as a standard of frequency.

- Quartz clocks employ a crystal oscillator made from a quartz crystal that uses a combination of both direct and converse piezoelectricity to generate a regularly timed series of electrical pulses that is used to mark time. The quartz crystal (like any elastic material) has a precisely defined natural frequency (caused by its shape and size) at which it prefers to oscillate, and this is used to stabilize the frequency of a periodic voltage applied to the crystal.

- The same principle is used in some radio transmitters and receivers, and in computers where it creates a clock pulse. Both of these usually use a frequency multiplier to reach gigahertz ranges.

Piezoelectric motors

Types of piezoelectric motor include:

- The traveling-wave motor used for auto-focus in reflex cameras

- Inchworm motors for linear motion

- Rectangular four-quadrant motors with high power density (2.5 W/cm3) and speed ranging from 10 nm/s to 800 mm/s.

- Stepping piezo motor, using stick-slip effect.

Aside from the stepping stick-slip motor, all these motors work on the same principle. Driven by dual orthogonal vibration modes with a phase difference of 90°, the contact point between two surfaces vibrates in an elliptical path, producing a frictional force between the surfaces. Usually, one surface is fixed, causing the other to move. In most piezoelectric motors, the piezoelectric crystal is excited by a sine wave signal at the resonant frequency of the motor. Using the resonance effect, a much lower voltage can be used to produce a high vibration amplitude.

A stick-slip motor works using the inertia of a mass and the friction of a clamp. Such motors can be very small. Some are used for camera sensor displacement, thus allowing an anti-shake function.

Reduction of vibrations and noise

Different teams of researchers have been investigating ways to reduce vibrations in materials by attaching piezo elements to the material. When the material is bent by a vibration in one direction, the vibration-reduction system responds to the bend and sends electric power to the piezo element to bend in the other direction. Future applications of this technology are expected in cars and houses to reduce noise. Further applications to flexible structures, such as shells and plates, have also been studied for nearly three decades.

In a demonstration at the Material Vision Fair in Frankfurt in November 2005, a team from TU Darmstadt in Germany showed several panels that were hit with a rubber mallet, and the panel with the piezo element immediately stopped swinging.

Piezoelectric ceramic fiber technology is being used as an electronic damping system on some HEAD tennis rackets.[54]

All piezo transducers have a fundamental resonant frequency and many harmonic frequencies. Piezo driven Drop-On-Demand fluid systems are sensitive to extra vibrations in the piezo structure that must be reduced or eliminated. One inkjet company, Howtek, Inc solved this problem by replacing glass(rigid) inkjet nozzles with Tefzel (soft) inkjet nozzles. This novel idea popularized single nozzle inkjets and they are now used in 3D Inkjet printers that run for years if kept clean inside and not overheated (Tefzel creeps under pressure at very high temperatures)

Infertility treatment

In people with previous total fertilization failure, piezoelectric activation of oocytes together with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) seems to improve fertilization outcomes.[55]

Surgery

Piezosurgery[4] Piezosurgery is a minimally invasive technique that aims to cut a target tissue with little damage to neighboring tissues. For example, Hoigne et al.[56] uses frequencies in the range 25–29 kHz, causing microvibrations of 60–210 μm. It has the ability to cut mineralized tissue without cutting neurovascular tissue and other soft tissue, thereby maintaining a blood-free operating area, better visibility and greater precision.[57]

Potential applications

In 2015, Cambridge University researchers working in conjunction with researchers from the National Physical Laboratory and Cambridge-based dielectric antenna company Antenova Ltd, using thin films of piezoelectric materials found that at a certain frequency, these materials become not only efficient resonators, but efficient radiators as well, meaning that they can potentially be used as antennas. The researchers found that by subjecting the piezoelectric thin films to an asymmetric excitation, the symmetry of the system is similarly broken, resulting in a corresponding symmetry breaking of the electric field, and the generation of electromagnetic radiation.[58][59]

Several attempts at the macro-scale application of the piezoelectric technology have emerged[60][61] to harvest kinetic energy from walking pedestrians.

In this case, locating high traffic areas is critical for optimization of the energy harvesting efficiency, as well as the orientation of the tile pavement significantly affects the total amount of the harvested energy.[62] A density flow evaluation is recommended to qualitatively evaluate the piezoelectric power harvesting potential of the considered area based on the number of pedestrian crossings per unit time.[63] In X. Li's study, the potential application of a commercial piezoelectric energy harvester in a central hub building at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia is examined and discussed. Optimization of the piezoelectric tile deployment is presented according to the frequency of pedestrian mobility and a model is developed where 3.1% of the total floor area with the highest pedestrian mobility is paved with piezoelectric tiles. The modelling results indicate that the total annual energy harvesting potential for the proposed optimized tile pavement model is estimated at 1.1 MW h/year, which would be sufficient to meet close to 0.5% of the annual energy needs of the building.[63] In Israel, there is a company which has installed piezoelectric materials under a busy highway. The energy generated is adequate and powers street lights, billboards and signs.

Tire company Goodyear has plans to develop an electricity generating tire which has piezoelectric material lined inside it. As the tire moves, it deforms and thus electricity is generated.[64]

Photovoltaics

The efficiency of a hybrid photovoltaic cell that contains piezoelectric materials can be increased simply by placing it near a source of ambient noise or vibration. The effect was demonstrated with organic cells using zinc oxide nanotubes. The electricity generated by the piezoelectric effect itself is a negligible percentage of the overall output. Sound levels as low as 75 decibels improved efficiency by up to 50%. Efficiency peaked at 10 kHz, the resonant frequency of the nanotubes. The electrical field set up by the vibrating nanotubes interacts with electrons migrating from the organic polymer layer. This process decreases the likelihood of recombination, in which electrons are energized but settle back into a hole instead of migrating to the electron-accepting ZnO layer.[65][66]

See also

References

- Holler, F. James; Skoog, Douglas A. & Crouch, Stanley R. (2007). Principles of Instrumental Analysis (6th ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-495-01201-6.

- Harper, Douglas. "piezoelectric". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- πιέζειν, ἤλεκτρον. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Manbachi, A. & Cobbold, R.S.C. (2011). "Development and Application of Piezoelectric Materials for Ultrasound Generation and Detection". Ultrasound. 19 (4): 187–96. doi:10.1258/ult.2011.011027. S2CID 56655834.

- Gautschi, G. (2002). Piezoelectric Sensorics: Force, Strain, Pressure, Acceleration and Acoustic Emission Sensors, Materials and Amplifiers. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-04732-3. ISBN 978-3-662-04732-3.

- Krautkrämer, J. & Krautkrämer, H. (1990). Ultrasonic Testing of Materials. Springer. pp. 119–149. ISBN 978-3-662-10680-8.

- "How Do Electronic Drums Work? A Beginners Guide To Digital Kits". Studio D: Artist Interviews, Gear Reviews, Product News | Dawsons Music. 2019-04-10. Retrieved 2019-10-01.

- "Piezo Drum Kit Quickstart Guide". www.sparkfun.com – SparkFun Electronics. Retrieved 2019-10-01.

- Erhart, Jiří. "Piezoelectricity and ferroelectricity: Phenomena and properties" (PDF). Department of Physics, Technical University of Liberec. Archived from the original on May 8, 2014.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- Curie, Jacques; Curie, Pierre (1880). "Développement par compression de l'électricité polaire dans les cristaux hémièdres à faces inclinées" [Development, via compression, of electric polarization in hemihedral crystals with inclined faces]. Bulletin de la Société Minérologique de France. 3 (4): 90–93. doi:10.3406/bulmi.1880.1564.

Reprinted in: Curie, Jacques; Curie, Pierre (1880). "Développement, par pression, de l'électricité polaire dans les cristaux hémièdres à faces inclinées". Comptes Rendus (in French). 91: 294–295. Archived from the original on 2012-12-05.

See also: Curie, Jacques; Curie, Pierre (1880). "Sur l'électricité polaire dans les cristaux hémièdres à faces inclinées" [On electric polarization in hemihedral crystals with inclined faces]. Comptes Rendus (in French). 91: 383–386. Archived from the original on 2012-12-05. - Lippmann, G. (1881). "Principe de la conservation de l'électricité" [Principle of the conservation of electricity]. Annales de chimie et de physique (in French). 24: 145. Archived from the original on 2016-02-08.

- Curie, Jacques; Curie, Pierre (1881). "Contractions et dilatations produites par des tensions dans les cristaux hémièdres à faces inclinées" [Contractions and expansions produced by voltages in hemihedral crystals with inclined faces]. Comptes Rendus (in French). 93: 1137–1140. Archived from the original on 2012-12-05.

- Voigt, Woldemar (1910). Lehrbuch der Kristallphysik. Berlin: B. G. Teubner. Archived from the original on 2014-04-21.

- Katzir, S. (2012). "Who knew piezoelectricity? Rutherford and Langevin on submarine detection and the invention of sonar". Notes Rec. R. Soc. 66 (2): 141–157. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2011.0049.

- M. Birkholz (1995). "Crystal-field induced dipoles in heteropolar crystals – II. physical significance". Z. Phys. B. 96 (3): 333–340. Bibcode:1995ZPhyB..96..333B. doi:10.1007/BF01313055. S2CID 122393358. Archived from the original on 2016-10-30.

- S. Trolier-McKinstry (2008). "Chapter 3: Crystal Chemistry of Piezoelectric Materials". In A. Safari; E.K. Akdo˘gan (eds.). Piezoelectric and Acoustic Materials for Transducer Applications. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-76538-9.

- Robert Repas (2008-02-07). "Sensor Sense: Piezoelectric Force Sensors". Machinedesign.com. Archived from the original on 2010-04-13. Retrieved 2012-05-04.

- IEC 80000-6, item 6-12

- "IEC 60050 - International Electrotechnical Vocabulary - Details for IEV number 121-11-40: "electric flux density"". www.electropedia.org.

- Ikeda, T. (1996). Fundamentals of piezoelectricity. Oxford University Press.

- Damjanovic, Dragan (1998). "Ferroelectric, dielectric and piezoelectric properties of ferroelectric thin films and ceramics". Reports on Progress in Physics. 61 (9): 1267–1324. Bibcode:1998RPPh...61.1267D. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/61/9/002.

- Kochervinskii, V. (2003). "Piezoelectricity in Crystallizing Ferroelectric Polymers". Crystallography Reports. 48 (4): 649–675. Bibcode:2003CryRp..48..649K. doi:10.1134/1.1595194. S2CID 95995717.

- "Piezoelectric Crystal Classes". Newcastle University, UK. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- "Pyroelectric Crystal Classes". Newcastle University, UK. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- Akizuki, Mizuhiko; Hampar, Martin S.; Zussman, Jack (1979). "An explanation of anomalous optical properties of topaz" (PDF). Mineralogical Magazine. 43 (326): 237–241. Bibcode:1979MinM...43..237A. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.604.6025. doi:10.1180/minmag.1979.043.326.05.

- Radusinović, Dušan & Markov, Cvetko (1971). "Macedonite – lead titanate: a new mineral" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 56: 387–394. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-05.

- Burke, E. A. J. & Kieft, C. (1971). "Second occurrence of makedonite, PbTiO3, Långban, Sweden". Lithos. 4 (2): 101–104. Bibcode:1971Litho...4..101B. doi:10.1016/0024-4937(71)90102-2.

- Jaffe, B.; Cook, W. R.; Jaffe, H. (1971). Piezoelectric Ceramics. New York: Academic.

- Ganeshkumar, Rajasekaran; Somnath, Suhas; Cheah, Chin Wei; Jesse, Stephen; Kalinin, Sergei V.; Zhao, Rong (2017-12-06). "Decoding Apparent Ferroelectricity in Perovskite Nanofibers". ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 9 (48): 42131–42138. doi:10.1021/acsami.7b14257. ISSN 1944-8244. PMID 29130311.

- Saito, Yasuyoshi; Takao, Hisaaki; Tanil, Toshihiko; Nonoyama, Tatsuhiko; Takatori, Kazumasa; Homma, Takahiko; Nagaya, Toshiatsu; Nakamura, Masaya (2004-11-04). "Lead-free piezoceramics". Nature. 432 (7013): 81–87. Bibcode:2004Natur.432...84S. doi:10.1038/nature03028. PMID 15516921. S2CID 4352954.

- Gurdal, Erkan A.; Ural, Seyit O.; Park, Hwi-Yeol; Nahm, Sahn; Uchino, Kenji (2011). "High Power (Na0.5K0.5)NbO3-Based Lead-Free Piezoelectric Transformer". Japanese Journal of Applied Physics. 50 (2): 027101. Bibcode:2011JaJAP..50b7101G. doi:10.1143/JJAP.50.027101. ISSN 0021-4922.

- Ibn-Mohammed, T., Koh, S., Reaney, I., Sinclair, D., Mustapha, K., Acquaye, A., & Wang, D. (2017). "Are lead-free piezoelectrics more environmentally friendly?" MRS Communications, 7(1), 1-7. doi: 10.1557/mrc.2017.10

- Wu, Jiagang. (2020). "Perovskite lead-free piezoelectric ceramics." Journal of Applied Physics, 127 (19). doi: 10.1063/5.0006261

- Migliorato, Max; et al. (2014). "A Review of Non Linear Piezoelectricity in Semiconductors". AIP Conf Proc. AIP Conference Proceedings. 1590 (N/A): 32–41. Bibcode:2014AIPC.1590...32M. doi:10.1063/1.4870192.

- Heywang, Walter; Lubitz, Karl; Wersing, Wolfram, eds. (2008). Piezoelectricity : evolution and future of a technology. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3540686835. OCLC 304563111.

- Sappati, Kiran; Bhadra, Sharmistha; Sappati, Kiran Kumar; Bhadra, Sharmistha (2018). "Piezoelectric Polymer and Paper Substrates: A Review". Sensors. 18 (11): 3605. doi:10.3390/s18113605. PMC 6263872. PMID 30355961.

- Ma, Si Wei; Fan, You Jun; Li, Hua Yang; Su, Li; Wang, Zhong Lin; Zhu, Guang (2018-09-07). "Flexible Porous Polydimethylsiloxane/Lead Zirconate Titanate-Based Nanogenerator Enabled by the Dual Effect of Ferroelectricity and Piezoelectricity". ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 10 (39): 33105–33111. doi:10.1021/acsami.8b06696. ISSN 1944-8244. PMID 30191707.

- Chen, Xiaoliang; Parida, Kaushik; Wang, Jiangxin; Xiong, Jiaqing; Lin, Meng-Fang; Shao, Jinyou; Lee, Pooi See (2017-11-20). "A Stretchable and Transparent Nanocomposite Nanogenerator for Self-Powered Physiological Monitoring". ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 9 (48): 42200–42209. doi:10.1021/acsami.7b13767. ISSN 1944-8244. PMID 29111642.

- Moody, M. J.; Marvin, C. W.; Hutchison, G. R. (2016). "Molecularly-doped polyurethane foams with massive piezoelectric response". Journal of Materials Chemistry C. 4 (20): 4387–4392. doi:10.1039/c6tc00613b. ISSN 2050-7526.

- Lee, B. Y.; Zhang, J.; Zueger, C.; Chung, W. J.; Yoo, S. Y.; Wang, E.; Meyer, J.; Ramesh, R.; Lee, S. W. (2012-05-13). "Virus-based piezoelectric energy generation". Nature Nanotechnology. 7 (6): 351–356. Bibcode:2012NatNa...7..351L. doi:10.1038/nnano.2012.69. PMID 22581406.

- Tao, Kai; et, al (2019). "Stable and Optoelectronic Dipeptide Assemblies for Power Harvesting". Materials Today. 30: 10–16. doi:10.1016/j.mattod.2019.04.002. PMC 6850901. PMID 31719792.

- Guerin, Sarah; Stapleton, Aimee; Chovan, Drahomir; Mouras, Rabah; Gleeson, Matthew; McKeown, Cian; Noor, Mohamed Radzi; Silien, Christophe; Rhen, Fernando M. F.; Kholkin, Andrei L.; Liu, Ning (February 2018). "Control of piezoelectricity in amino acids by supramolecular packing". Nature Materials. 17 (2): 180–186. doi:10.1038/nmat5045. ISSN 1476-1122. PMID 29200197.

- "Market Report: World Piezoelectric Device Market". Market Intelligence. Archived from the original on 2011-07-03.

- Richard, Michael Graham (2006-08-04). "Japan: Producing Electricity from Train Station Ticket Gates". TreeHugger. Discovery Communications, LLC. Archived from the original on 2007-07-09.

- Wright, Sarah H. (2007-07-25). "MIT duo sees people-powered "Crowd Farm"". MIT news. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 2007-09-12.

- Kannampilly, Ammu (2008-07-11). "How to Save the World One Dance at a Time". ABC News. Archived from the original on 2010-10-31.

- Barbehenn, George H. (October 2010). "True Grid Independence: Robust Energy Harvesting System for Wireless Sensors Uses Piezoelectric Energy Harvesting Power Supply and Li-Poly Batteries with Shunt Charger". Journal of Analog Innovation: 36.

- Phillips, James R. (2000-08-10). "Piezoelectric Technology: A Primer". eeProductCenter. TechInsights. Archived from the original on 2010-10-06.

- Speck, Shane (2004-03-11). "How Rocket-Propelled Grenades Work by Shane Speck". HowStuffWorks.com. Archived from the original on 2012-04-29. Retrieved 2012-05-04.

- Moubarak, P.; et al. (2012). "A Self-Calibrating Mathematical Model for the Direct Piezoelectric Effect of a New MEMS Tilt Sensor". IEEE Sensors Journal. 12 (5): 1033–1042. Bibcode:2012ISenJ..12.1033M. doi:10.1109/jsen.2011.2173188. S2CID 44030488.

- Shabestari, N. P. (2019). "Fabrication of a simple and easy-to-make piezoelectric actuator and its use as phase shifter in digital speckle pattern interferometry". Journal of Optics. 48 (2): 272–282. doi:10.1007/s12596-019-00522-4. S2CID 155531221.

- Le Letty, R.; Barillot, F.; Lhermet, N.; Claeyssen, F.; Yorck, M.; Gavira Izquierdo, J.; Arends, H. (2001). "The scanning mechanism for ROSETTA/MIDAS from an engineering model to the flight model". In Harris, R. A. (ed.). Proceedings of the 9th European Space Mechanisms and Tribology Symposium, 19–21 September 2001, Liège, Belgium. 9th European Space Mechanisms and Tribology Symposium. ESA SP-480. 480. pp. 75–81. Bibcode:2001ESASP.480...75L. ISBN 978-92-9092-761-7.

- Simonsen, Torben R. (27 September 2010). "Piezo in space". Electronics Business (in Danish). Archived from the original on 29 September 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- "Isn't it amazing how one smart idea, one chip and an intelligent material has changed the world of tennis?". Head.com. Archived from the original on February 22, 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- Baltaci, Volkan; Ayvaz, Özge Üner; Ünsal, Evrim; Aktaş, Yasemin; Baltacı, Aysun; Turhan, Feriba; Özcan, Sarp; Sönmezer, Murat (2009). "The effectiveness of intracytoplasmic sperm injection combined with piezoelectric stimulation in infertile couples with total fertilization failure". Fertil. Steril. 94 (3): 900–904. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.107. PMID 19464000.

- Hoigne, D.J.; Stubinger, S.; von Kaenel, O.; Shamdasani, S.; Hasenboehler, P. (2006). "Piezoelectric osteotomy in hand surgery: first experiences with a new technique". BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 7: 36. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-7-36. PMC 1459157. PMID 16611362.

- Labanca, M.; Azzola, F.; Vinci, R.; Rodella, L. F. (2008). "Piezoelectric surgery: twenty years of use". Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 46 (4): 265–269. doi:10.1016/j.bjoms.2007.12.007. PMID 18342999.

- Sinha, Dhiraj; Amaratunga, Gehan (2015). "Electromagnetic Radiation Under Explicit symmetry Breaking". Physical Review Letters. 114 (14): 147701. Bibcode:2015PhRvL.114n7701S. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.114.147701. PMID 25910163.

- "New understanding of electromagnetism could enable 'antennas on a chip'". cam.ac.uk. 2015-04-09. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- Takefuji, Y. (April 2008). "And if public transport does not consume more of energy?" (PDF). Le Rail: 31–33.

- Takefuji, Y. (September 2008). Known and unknown phenomena of nonlinear behaviors in the power harvesting mat and the transverse wave speaker (PDF). international symposium on nonlinear theory and its applications.

- Deutz, D.B.; Pascoe, J.-A.; van der Zwaag, S.; de Leeuw, D.M.; Groen, P. (2018). "Analysis and experimental validation of the figure of merit for piezoelectric energy harvesters". Materials Horizons. 5 (3): 444–453. doi:10.1039/c8mh00097b.

- Li, Xiaofeng; Strezov, Vladimir (2014). "Modelling piezoelectric energy harvesting potential in an educational building". Energy Conversion and Management. 85: 435–442. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2014.05.096.

- "Goodyear Is Trying to Make an Electricity-Generating Tire". WIRED. 2015-03-12. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- Heidi Hoopes (November 8, 2013). "Good vibrations lead to efficient excitations in hybrid solar cells". Gizmag.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2013. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

- Shoaee, S.; Briscoe, J.; Durrant, J. R.; Dunn, S. (2013). "Acoustic Enhancement of Polymer/ZnO Nanorod Photovoltaic Device Performance". Advanced Materials. 26 (2): 263–268. doi:10.1002/adma.201303304. PMID 24194369.

International standards

- EN 50324 (2002) Piezoelectric properties of ceramic materials and components (3 parts)

- ANSI-IEEE 176 (1987) Standard on Piezoelectricity

- IEEE 177 (1976) Standard Definitions & Methods of Measurement for Piezoelectric Vibrators

- IEC 444 (1973) Basic method for the measurement of resonance freq & equiv series resistance of quartz crystal units by zero-phase technique in a pi-network

- IEC 302 (1969) Standard Definitions & Methods of Measurement for Piezoelectric Vibrators Operating over the Freq Range up to 30 MHz

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Piezoelectricity. |

- Gautschi, Gustav H. (2002). Piezoelectric Sensorics. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-42259-4.

- Piezoelectric cellular polymer films: Fabrication, properties and applications

- Piezo motor based microdrive for neural signal recording

- Research on new Piezoelectric materials

- Piezo Equations

- Piezo in Medical Design

- Video demonstration of Piezoelectricity

- DoITPoMS Teaching and Learning Package – Piezoelectric Materials

- PiezoMat.org – Online database for piezoelectric materials, their properties, and applications

- Piezo Motor Types

- Piezo-Theory & Applications