Process chemistry

Process chemistry is the arm of pharmaceutical chemistry concerned with the development and optimization of a synthetic scheme and pilot plant procedure to manufacture compounds for the drug development phase. Process chemistry is distinguished from medicinal chemistry, which is the arm of pharmaceutical chemistry tasked with designing and synthesizing molecules on small scale in the early drug discovery phase.

Medicinal chemists are largely concerned with synthesizing a large number of compounds as quickly as possible from easily tunable chemical building blocks (usually for SAR studies). In general, the repertoire of reactions utilized in discovery chemistry is somewhat narrow (for example, the Buchwald-Hartwig amination, Suzuki coupling and reductive amination are commonplace reactions).[1] In contrast, process chemists are tasked with identifying a chemical process that is safe, cost and labor efficient, “green,” and reproducible, among other considerations. Oftentimes, in searching for the shortest, most efficient synthetic route, process chemists must devise creative synthetic solutions that eliminate costly functional group manipulations and oxidation/reduction steps.

This article focuses exclusively on the chemical and manufacturing processes associated with the production of small molecule drugs. Biological medical products (more commonly called “biologics”) represent a growing proportion of approved therapies, but the manufacturing processes of these products are beyond the scope of this article. Additionally, the many complex factors associated with chemical plant engineering (for example, heat transfer and reactor design) and drug formulation will be treated cursorily.

Process chemistry considerations

Cost efficiency is of paramount importance in process chemistry and, consequently, is a focus in the consideration of pilot plant synthetic routes. The drug substance that is manufactured, prior to formulation, is commonly referred to as the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and will be referred to as such herein. API production cost can be broken into two components: the “material cost” and the “conversion cost.”[2] The ecological and environmental impact of a synthetic process should also be evaluated by an appropriate metric (e.g. the EcoScale).

An ideal process chemical route will score well in each of these metrics, but inevitably tradeoffs are to be expected. Most large pharmaceutical process chemistry and manufacturing divisions have devised weighted quantitative schemes to measure the overall attractiveness of a given synthetic route over another. As cost is a major driver, material cost and volume-time output are typically weighted heavily.

Material cost

The material cost of a chemical process is the sum of the costs of all raw materials, intermediates, reagents, solvents and catalysts procured from external vendors. Material costs may influence the selection of one synthetic route over another or the decision to outsource production of an intermediate.

Conversion cost

The conversion cost of a chemical process is a factor of that procedure's overall efficiency, both in materials and time, and its reproducibility. The efficiency of a chemical process can be quantified by its atom economy, yield, volume-time output, and environmental factor (E-factor), and its reproducibility can be evaluated by the Quality Service Level (QSL) and Process Excellence Index (PEI) metrics.

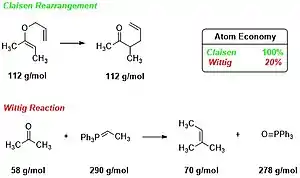

Atom economy

The atom economy of a reaction is defined as the number of atoms from the starting materials that are incorporated into the final product. Atom economy can be viewed as an indicator of the “efficiency” of a given synthetic route.[3]

For example, the Claisen rearrangement and the Diels-Alder cycloaddition are examples of reaction that are 100 percent atom economical. On the other hand, a prototypical Wittig reaction has especially poor atom economy (merely 20 percent in the example shown).

Process synthetic routes should be designed such that atom economy is maximized for the entire synthetic scheme. Consequently, “costly” reagents such as protecting groups and high molecular weight leaving groups should be avoided where possible. An atom economy value in the range of 70 to 90 percent for an API synthesis is ideal, but it may be impractical or impossible to access certain complex targets within this range. Nevertheless, atom economy is a good metric to compare two routes to the same molecule.

Yield

Yield is defined as the amount of product obtained in a chemical reaction the yield of practical significance in process chemistry is the isolated yield—the yield of the isolated product after all purification steps. In a final API synthesis, isolated yields of 80 percent or above for each synthetic step are expected. The definition of an acceptable yield depends entirely on the importance of the product and the ways in which available technologies come together to allow their efficient application; yields approaching 100% are termed quantitative, and yields above 90% are broadly understood as excellent.[4]

There are several strategies that are employed in the design of a process route to ensure adequate overall yield of the pharmaceutical product. The first is the concept of convergent synthesis. Assuming a very good to excellent yield in each synthetic step, the overall yield of a multistep reaction can be maximized by combining several key intermediates at a late stage that are prepared independently from each other.

Another strategy to maximize isolated yield (as well as time efficiency) is the concept of telescoping synthesis (also called one-pot synthesis). This approach describes the process of eliminating workup and purification steps from a reaction sequence, typically by simply adding reagents sequentially to a reactor. In this way, unnecessary losses from these steps can be avoided.

Finally, to minimize overall cost, synthetic steps involving expensive reagents, solvents or catalysts should be designed into the process route as late stage as possible, to minimize the amount of reagent used.

In a pilot plant or manufacturing plant setting, yield can have a profound effect on the material cost of an API synthesis, so the careful planning of a robust route and the fine-tuning of reaction conditions are crucially important. After a synthetic route has been selected, process chemists will subject each step to exhaustive optimization in order to maximize overall yield. Low yields are typically indicative of unwanted side product formation, which can raise red flags in the regulatory process as well as pose challenges for reactor cleaning operations.

Volume-time output

The volume-time output (VTO) of a chemical process represents the cost of occupancy of a chemical reactor for a particular process or API synthesis. For example, a high VTO indicates that a particular synthetic step is costly in terms of “reactor hours” used for a given output. Mathematically, the VTO for a particular process is calculated by the total volume of all reactors (m3) that are occupied times the hours per batch divided by the output for that batch of API or intermediate (measured in kg).

The process chemistry group at Boehringer Ingelheim, for example, targets a VTO of less than 1 for any given synthetic step or chemical process.

Additionally, the raw conversion cost of an API synthesis (in dollars per batch) can be calculated from the VTO, given the operating cost and usable capacity of a particular reactor. Oftentimes, for large-volume APIs, it is economical to build a dedicated production plant rather than to use space in general pilot plants or manufacturing plants.

Environmental factor (e-factor) and process mass intensity (PMI)

Both of these measures, which capture the environmental impact of a synthetic reaction, intend to capture the significant and rising cost of waste disposal in the manufacturing process. The E-factor for an entire API process is computed by the ratio of the total mass of waste generated in the synthetic scheme to the mass of product isolated.

A similar measure, the process mass intensity (PMI) calculates the ratio of the total mass of materials to the mass of the isolated product.

For both metrics, all materials used in all synthetic steps, including reaction and workup solvents, reagents and catalysts, are counted, even if solvents or catalysts are recycled in practice. Inconsistencies in E-factor or PMI computations may arise when choosing to consider the waste associated with the synthesis of outsourced intermediates or common reagents. Additionally, the environmental impact of the generated waste is ignored in this calculation; therefore, the environmental quotient (EQ) metric was devised, which multiplies the E-factor by an “unfriendliness quotient” associated with various waste streams. A reasonable target for the E-factor or PMI of a single synthetic step is any value between 10 and 40.

Quality service level (QSL)

The final two "conversion cost" considerations involve the reproducibility of a given reaction or API synthesis route. The quality service level (QSL) is a measure of the reproducibility of the quality of the isolated intermediate or final API. While the details of computing this value are slightly nuanced and unimportant for the purposes of this article, in essence, the calculation involves the ratio of satisfactory quality batches to the total number of batches. A reasonable QSL target is 98 to 100 percent.

Process excellence index (PEI)

Like the QSL, the process excellence index (PEI) is a measure of process reproducibility. Here, however, the robustness of the procedure is evaluated in terms of yield and cycle time of various operations. The PEI yield is defined as follows:

In practice, if a process is high-yielding and has a narrow distribution of yield outcomes, then the PEI should be very high. Processes that are not easily reproducible may have a higher aspiration level yield and a lower average yield, lowering the PEI yield.

Similarly, a PEI cycle time may be defined as follows:

For this expression, the terms are inverted to reflect the desirability of shorter cycle times (as opposed to higher yields). The reproducibility of cycle times for critical processes such as reaction, centrifugation or drying may be critical if these operations are rate-limiting in the manufacturing plant setting. For example, if an isolation step is particularly difficult or slow, it could become the bottleneck for an API synthesis, in which case the reproducibility and optimization of that operation become critical.

For an API manufacturing process, all PEI metrics (yield and cycle times) should be targeted at 98 to 100 percent.

EcoScale

In 2006, Van Aken, et al.[5] developed a quantitative framework to evaluate the safety and ecological impact of a chemical process, as well as minor weighting of practical and economical considerations. Others have modified this EcoScale by adding, subtracting and adjusting the weighting of various metrics. Among other factors, the EcoScale takes into account the toxicity, flammability and explosive stability of reagents used, any nonstandard or potentially hazardous reaction conditions (for example, elevated pressure or inert atmosphere), and reaction temperature. Some EcoScale criteria are redundant with previously considered criteria (e.g. E-factor).

Synthetic case studies

Boehringer Ingelheim HCV protease inhibitor (BI 201302)

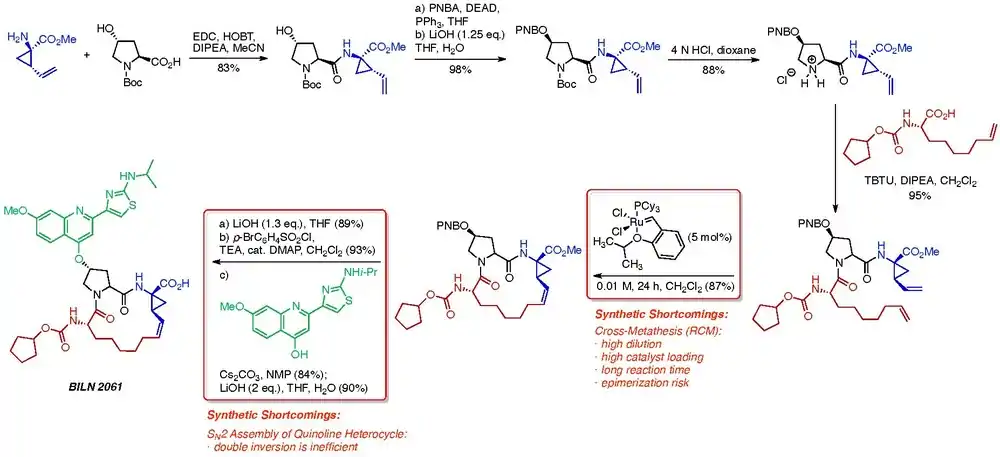

Macrocyclization is a recurrent challenge for process chemists, and large pharmaceutical companies have necessarily developed creative strategies to overcome these inherent limitations. An interesting case study in this area involves the development of novel NS3 protease inhibitors to treat Hepatitis C patients by scientists at Boehringer Ingelheim.[6] The process chemistry team at BI was tasked with developing a cheaper and more efficient route to the active NS3 inhibitor BI 201302, a close analog of BILN 2061. Two significant shortcomings were immediately identified with the initial scale-up route to BILN 2061, depicted in the scheme below.[7] The macrocyclization step posed four challenges inherent to the cross-metathesis reaction.

- High dilution is typically necessary to prevent unwanted dimerization and oligomerization of the diene starting material. In a pilot plant setting, however, a high dilution factor translates into lower throughput, higher solvent costs and higher waste costs.

- High catalyst loading was found to be necessary to drive the RCM reaction to completion. Because of high licensing costs of the ruthenium catalyst that was used (1st generation Hoveyda catalyst), a high catalyst loading was financially prohibitive. Recycling of the catalyst was explored, but proved impractical.

- Long reaction times were necessary for reaction completion, due to slow kinetics of the reaction using the selected catalyst. It was hypothesized that this limitation could be overcome using a more active catalyst. However, while the second-generation Hoveyda and Grubbs catalysts were kinetically more active than the first-generation catalyst, reactions using these catalysts formed large amounts of dimeric and oligomeric products.

- An epimerization risk under the cross-metathesis reaction conditions. The process chemistry group at Boehringer Ingelheim performed extensive mechanistic studies showing that epimerization most likely occurs through a ruthenacyclopentene intermediate.[8] Furthermore, the Hoveyda catalyst employed in this scheme minimizes epimerization risk compared with the analogous Grubbs catalyst.

Additionally, the final double SN2 sequence to install the quinoline heterocycle was identified as a secondary inefficiency in the synthetic route.

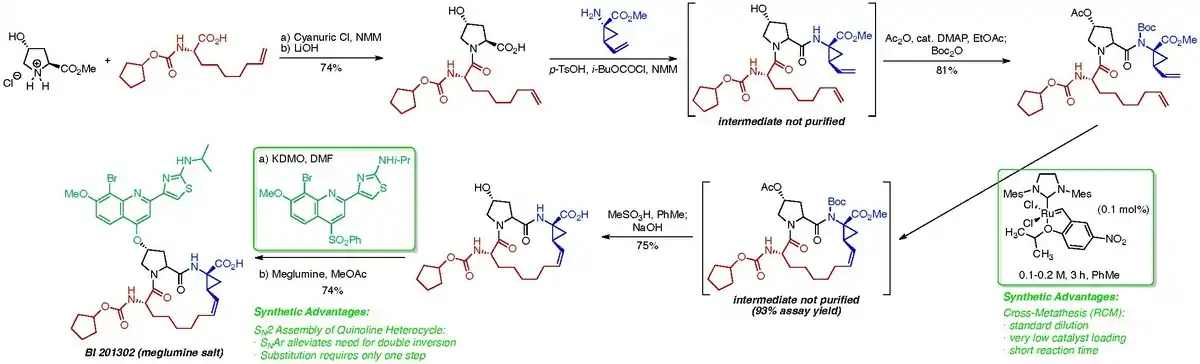

Analysis of the cross-methathesis reaction revealed that the conformation of the acyclic precursor had a profound impact on the formation of dimers and oligomers in the reaction mixture. By installing a Boc protecting group at the C-4 amide nitrogen, the Boehringer Ingelheim chemists were able to shift the site of initiation from the vinylcyclopropane moiety to the nonenoic acid moiety, improving the rate of the intramolecular reaction and decreasing the risk of epimerization. Additionally, the catalyst employed was switched from the expensive 1st generation Hoveyda catalyst to the more reactive, less expensive Grela catalyst.[9] These modifications allowed the process chemists to run the reaction at a standard reaction dilution of 0.1-0.2 M, given that the rates of competing dimerization and oligomerization reactions was so dramatically reduced.

Additionally, the process chemistry team envisioned a SNAr strategy to install the quinoline heterocycle, instead of the SN2 strategy that they had employed for the synthesis of BILN 2061. This modification prevented the need for inefficient double inversion by proceeding through retention of stereochemistry at the C-4 position of the hydroxyproline moiety.[10]

It is interesting to examine this case study from a VTO perspective. For the unoptimized cross-metathesis reaction using the Grela catalyst at 0.01 M diene, the reaction yield was determined to be 82 percent after a reaction and workup time of 48 hours. A 6-cubic meter reactor filled to 80% capacity afforded 35 kg of desired product. For the unoptimized reaction:

This VTO value was considered prohibitively high and a steep investment in a dedicated plant would have been necessary even before launching Phase III trials with this API, given its large projected annual demand. But after reaction development and optimization, the process team was able to improve the reaction yield to 93 percent after just 1 hour (plus 12 hours for workup and reactor cleaning time) at a diene concentration of 0.2 M. With these modifications, a 6-cubic meter reactor filled to 80% capacity afforded 799 kg of desired product. For this optimized reaction:

Thus, after optimization, this synthetic step became less costly in terms of equipment and time and more practical to perform in a standard manufacturing facility, eliminating the need for a costly investment in a new dedicated plant.

Additional topics

Biocatalysis and enzymatic engineering

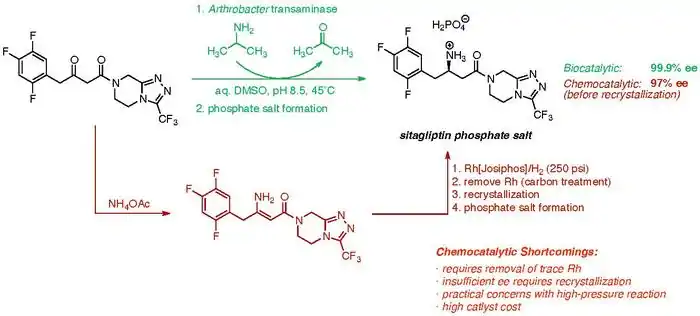

Recently, large pharmaceutical process chemists have relied heavily on the development of enzymatic reactions to produce important chiral building blocks for API synthesis. Many varied classes of naturally occurring enzymes have been co-opted and engineered for process pharmaceutical chemistry applications. The widest range of applications come from ketoreductases and transaminases, but there are isolated examples from hydrolases, aldolases, oxidative enzymes, esterases and dehalogenases, among others.[11]

One of the most prominent uses of biocatalysis in process chemistry today is in the synthesis of Januvia®, a DPP-4 inhibitor developed by Merck for the management of type II diabetes. The traditional process synthetic route involved a late-stage enamine formation followed by rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation to afford the API sitagliptin. This process suffered from a number of limitations, including the need to run the reaction under a high-pressure hydrogen environment, the high cost of a transition-metal catalyst, the difficult process of carbon treatment to remove trace amounts of catalyst and insufficient stereoselectivity, requiring a subsequent recrystallization step before final salt formation.[12][13]

Merck's process chemistry department contracted Codexis, a medium-sized biocatalysis firm, to develop a large-scale biocatalytic reductive amination for the final step of its sitagliptin synthesis. Codexis engineered a transaminase enzyme from the bacteria Arthrobacter through 11 rounds of directed evolution. The engineered transaminase contained 27 individual point mutations and displayed activity four orders of magnitude greater than the parent enzyme. Additionally, the enzyme was engineered to handle high substrate concentrations (100 g/L) and to tolerate the organic solvents, reagents and byproducts of the transamination reaction. This biocatalytic route successfully avoided the limitations of the chemocatalyzed hydrogenation route: the requirements to run the reaction under high pressure, to remove excess catalyst by carbon treatment and to recrystallize the product due to insufficient enantioselectivity were obviated by the use of a biocatalyst. Merck and Codexis were awarded the Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Award in 2010 for the development of this biocatalytic route toward Januvia®.[14]

Continuous/flow manufacturing

In recent years, much progress has been made in the development and optimization of flow reactors for small-scale chemical synthesis (the Jamison Group at MIT and Ley Group at Cambridge University, among others, have pioneered efforts in this field). The pharmaceutical industry, however, has been slow to adopt this technology for large-scale synthetic operations. For certain reactions, however, continuous processing may possess distinct advantages over batch processing in terms of safety, quality and throughput.

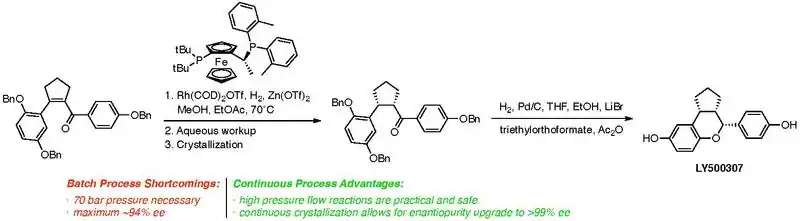

A case study of particular interest involves the development of a fully continuous process by the process chemistry group at Eli Lilly and Company for an asymmetric hydrogenation to access a key intermediate in the synthesis of LY500307,[15] a potent ERβ agonist that is entering clinical trials for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, in addition to a regimen of standard antipsychotic medications. In this key synthetic step, a chiral rhodium-catalyst is used for the enantioselective reduction of a tetrasubstituted olefin. After extensive optimization, it was found that in order to reduce the catalyst loading to a commercially practical level, the reaction required hydrogen pressure up to 70 atm. The pressure limit of a standard chemical reactor is about 10 atm, although high-pressure batch reactors may be acquired at significant capital cost for reactions up to 100 atm. Especially for an API in the early stages of chemical development, such an investment clearly bears a large risk.

An additional concern was that the hydrogenation product has an unfavorable eutectic point, so it was impossible to isolate the crude intermediate in more than 94 percent ee by batch process. Because of this limitation, the process chemistry route toward LY500307 necessarily involved a kinetically controlled crystallization step after the hydrogenation to upgrade the enantiopurity of this penultimate intermediate to >99 percent ee.

The process chemistry team at Eli Lilly successfully developed a fully continuous process to this penultimate intermediate, including reaction, workup and kinetically controlled crystallization modules (the engineering considerations implicit in these efforts are beyond the scope of this article). An advantage of flow reactors is that high-pressure tubing can be utilized for hydrogenation and other hyperbaric reactions. Because the head space of a batch reactor is eliminated, however, many of the safety concerns associated with running high-pressure reactions are obviated by the use of a continuous process reactor. Additionally, a two-stage mixed suspension-mixed product removal (MSMPR) module was designed for the scalable, continuous, kinetically controlled crystallization of the product, so it was possible to isolate in >99 percent ee, eliminating the need for an additional batch crystallization step.

This continuous process afforded 144 kg of the key intermediate in 86 percent yield, comparable with a 90 percent isolated yield using the batch process. This 73-liter pilot-scale flow reactor (occupying less than 0.5 m3 space) achieved the same weekly throughput as theoretical batch processing in a 400-liter reactor. Therefore, the continuous flow process demonstrates advantages in safety, efficiency (eliminates the need for batch crystallization) and throughput, compared with a theoretical batch process.

Academic research institutes in process chemistry

Institute of Process Research & Development, University of Leeds

References

- Roughley, S. D.; Jordan, A. M. (2011). "The medicinal chemist's toolbox: an analysis of reactions used in the pursuit of drug candidates". J. Med. Chem. 54 (10): 3451–79. doi:10.1021/jm200187y. PMID 21504168.

- Dach, R.; Song, J. J.; Roschangar, F.; Samstag, W.; Senanayake, C. H. (2012). "The eight criteria defining a good chemical manufacturing process". Org. Process Res. Dev. 16 (11): 1697–1706. doi:10.1021/op300144g.

- Trost, B. M. (1991). "The atom economy - a search for synthetic efficiency". Science. 254 (5037): 1471–7. Bibcode:1991Sci...254.1471T. doi:10.1126/science.1962206. PMID 1962206.

- In an academic perspective, Furniss, et al., in Vogel's Textbook of Practical Organic Chemistry, describes yields around 100% as quantitative, yields above 90% as excellent, above 80% as very good, above 70% as good, above 50% as fair, and yields below this as poor.

- Van Aken, K.; Strekowski, L.; Patiny, L. (2006). "EcoScale, a semi-quantitative tool to select an organic preparation based on economical and ecological parameters". Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2 (3): 3. doi:10.1186/1860-5397-2-3. PMC 1409775. PMID 16542013.

- Faucher, A-M.; Bailey, M. D.; Beaulieu, P. L.; Brochu, C.; Duceppe, J-S.; Ferland, J-M.; Ghiro, E.; Gorys, V.; Halmos, T.; Kawai, S. H.; Poirier, M.; Simoneau, B.; Tsantrizos, Y. S.; Llinas-Brunet, M. (2004). "Synthesis of BILN 2061, an HCV NS3 protease inhibitor with proven antiviral effect in humans". Org. Lett. 6 (17): 2901–2904. doi:10.1021/ol0489907. PMID 15330643.

- Yee, N. K.; Farina, V.; Houpis, I. N.; Haddad, N.; Frutos, R. P.; Gallou, F.; Wang, X-J.; Wei, X.; Simpson, R. D.; Feng, X.; Fuchs, V.; Xu, Y.; Tan, J.; Zhang, L.; Xu, J.; Smith-Keenan, L. L.; Vitous, J.; Ridges, M. D.; Spinelli, E. M.; Johnson, M. (2006). "Efficient large-scale synthesis of BILN 2061, a potent HCV protease inhibitor, by a convergent approach based on ring-closing metathesis". J. Org. Chem. 71 (19): 7133–7145. doi:10.1021/jo060285j. PMID 16958506.

- Zeng, X.; Wei, X.; Farina, V.; Napolitano, E.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Haddad, N.; Yee, N. K.; Grinberg, N.; Shen, S.; Senanayake, C. H. (2006). "Epimerization reaction of a substituted vinylcyclopropane catalyzed by ruthenium carbenes: mechanistic analysis". J. Org. Chem. 71 (23): 8864–8875. doi:10.1021/jo061587o. PMID 17081017.

- Grela, K.; Harutyunyan, S.; Michrowska, A. (2002). "A highly efficient ruthenium catalyst for metathesis reactions" (PDF). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41 (21): 4038–4040. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20021104)41:21<4038::aid-anie4038>3.0.co;2-0. PMID 12412074.

- Wei, X.; Shu, C.; Haddad, N.; Zeng, X.; Patel, N. D.; Tan, Z.; Liu, J.; Lee, H.; Shen, S.; Campbell, S.; Varsolona, R. J.; Busacca, C. A.; Hossain, A.; Yee, N. K.; Senanayake, C. H. (2013). "A highly convergent and efficient synthesis of a macrocyclic hepatitis C virus protease inhibitor BI 201302". Org. Lett. 15 (5): 1016–1019. doi:10.1021/ol303498m. PMID 23406520.

- Bornscheuer, U. T.; Huisman, G. W.; Kazlauskas, R. J.; Lutz, S.; Moore, J. C.; Robins, K. (2012). "Engineering the third wave of biocatalysis". Nature. 485 (7397): 185–94. Bibcode:2012Natur.485..185B. doi:10.1038/nature11117. PMID 22575958. S2CID 4379415.

- Savile, C. K.; Janey, J. M.; Mundorff, E. C.; Moore, J. C.; Tam, S.; Jarvis, W. R.; Colback, J. C.; Krebber, A.; Fleitz, F. J.; Brands, J.; Devine, P. N.; Huisman, G. W.; Hughes, G. J. (2010). "Biocatalytic asymmetric synthesis of chiral amines applied to sitagliptin manufacture". Science. 329 (5989): 305–309. doi:10.1126/science.1188934. PMID 20558668. S2CID 21954817.

- Desai, A. A. (2011). "Sitagliptin manufacture: a compelling tale of green chemistry, process intensification, and industrial asymmetric catalysis". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50 (9): 1974–1976. doi:10.1002/anie.201007051. PMID 21284073.

- Busacca, C. A.; Fandrick, D. R.; Song, J. J.; Sananayake, C. H. (2011). "The growing impact of catalysis in the pharmaceutical industry". Adv. Synth. Catal. 353 (11–12): 1825–1864. doi:10.1002/adsc.201100488.

- Johnson, M. D.; May, S. A.; Calvin, J. R.; Remacle, J.; Stout, J. R.; Dieroad, W. D.; Zaborenko, N.; Haeberle, B. D.; Sun, W-M.; Miller, M. T.; Brannan, J. (2012). "Development and scale-up of a continuous, high-pressure, asymmetric hydrogenation reaction, workup, and isolation". Org. Process Res. Dev. 16 (5): 1017–1038. doi:10.1021/op200362h.