Proto-Semitic language

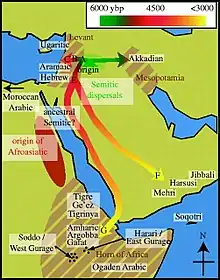

Proto-Semitic is the hypothetical reconstructed proto-language ancestral to the Semitic languages. A 2009 study proposes that it was spoken from about 3750 BC in the Levant during the Early Bronze Age.[1] There is no consensus regarding the location of the Proto-Semitic Urheimat; scholars hypothesize that it may have originated in the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, the Sahara, or the Horn of Africa.

| Proto-Semitic | |

|---|---|

| Reconstruction of | Semitic languages |

| Era | ca. 3750 BC |

Reconstructed ancestor | |

| Lower-order reconstructions | |

The Semitic language family is considered part of the broader macro-family of Afroasiatic languages.

Dating

The earliest attestations of a Semitic language are in Akkadian, dating to around the 23rd century BC (see Sargon of Akkad) and the Eblaite language, but earlier evidence of Akkadian comes from personal names in Sumerian texts around the 28th century BC. The earliest text fragments of West Semitic are snake spells in Egyptian pyramid texts, dated around the mid-third millennium BC.[2][3]

Urheimat

Since all modern Semitic languages can be traced back to a common ancestor, Semiticists have placed importance upon locating the urheimat of the Proto-Semitic language.[4] The Urheimat of the Proto-Semitic language may be considered within the context of the larger Afro-Asiatic family to which it belongs.

The previously popular hypothesis of an Arabian urheimat has been largely abandoned, since the region could not have supported massive waves of emigration before the domestication of camels in the second millennium BC.[4]

Levant hypothesis

A Bayesian analysis performed in 2009 suggests an origin for all known Semitic languages in the Levant around 3750 BC, with a later single introduction from South Arabia into the Horn of Africa around 800 BC. This statistical analysis could not, however, estimate when or where the ancestor of all Semitic languages diverged from Afroasiatic.[1] It thus neither contradicts nor confirms the hypothesis that the divergence of ancestral Semitic from Afroasiatic occurred in Africa.

Christopher Ehret has hypothesized that genetic analyses (specifically those of Y chromosome phylogeography and TaqI 49a,f haplotypes) shows populations of proto-Semitic speakers may have moved from the Horn of Africa or southeastern Sahara northwards to the Nile Valley, northwest Africa, the Levant, and Aegean.[5]

Some geneticists and archaeologists have argued for a back-migration of proto-Afroasiatic speakers from Western Asia to Africa as early as the 10th millennium BC. They suggest the Natufian culture might have spoken a proto-Afroasiatic language just prior to its disintegration into sub-languages.[6][7] The hypothesis is supported by the Afroasiatic terms for early livestock and crops in both Anatolia and Iran.[8]

North Africa hypothesis

Edward Lipiński believes that support for an African origin is provided by what he describes as a possible relationship between a pre-Semitic Afroasiatic language and the Niger–Congo languages, whose Urheimat probably lies in Nigeria–Cameroon.[9] According to this theory, the earliest wave of Semitic speakers entered the Fertile Crescent via Palestine and Syria and eventually founded the Akkadian Empire. Their relatives, the Amorites, followed them and settled Syria before 2500 BC.[10] Late Bronze Age collapse in Palestine led the southern Semites southwards, where they reached the highlands of Yemen after 20th century BC. Those crossed back to the Horn of Africa between 1500 and 500 BC.[10]

Phonology

Vowels

Proto-Semitic had a simple vowel system, with three qualities *a, *i, *u, and phonemic vowel length, conventionally indicated by a macron: *ā, *ī, *ū.[11] This system is preserved in Akkadian, Ugaritic and Classical Arabic.[12]

Consonants

The reconstruction of Proto-Semitic was originally based primarily on Arabic, whose phonology and morphology (particularly in Classical Arabic) is extremely conservative, and which preserves as contrastive 28 out of the evident 29 consonantal phonemes.[13] Thus, the phonemic inventory of reconstructed Proto-Semitic is very similar to that of Arabic, with only one phoneme fewer in Arabic than in reconstructed Proto-Semitic, with *s [s] and *š [ʃ] merging into Arabic /s/ ⟨س⟩ and *ś [ɬ] becoming Arabic /ʃ/ ⟨ش⟩. As such, Proto-Semitic is generally reconstructed as having the following phonemes (as usually transcribed in Semitology):[14]

| Type | Manner | Voicing | Labial | Interdental | Alveolar | Palatal | Lateral | Velar/Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstruent | Stop | voiceless | *p [p] | *t [t] | *k [k] | |||||

| emphatic | (pʼ)[lower-alpha 1] | *ṭ [tʼ] | *q/ḳ [kʼ] | *ʼ,ˀ [ʔ] | ||||||

| voiced | *b [b] | *d [d] | *g [g] | |||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | *ṯ [θ] | *s [s] | *š [ʃ] | *ś [ɬ] | *ḫ [x~χ] | *ḥ [ħ] | *h [h] | ||

| emphatic | *ṯ̣/θ̣/ẓ [θʼ] | *ṣ [sʼ] | *ṣ́/ḏ̣ [ɬʼ] | (xʼ~χʼ)[lower-alpha 2] | ||||||

| voiced | *ḏ [ð] | *z [z] | *ġ/ǵ [ɣ~ʁ] | *ʻ,ˤ [ʕ] | ||||||

| Resonant | Trill | *r [r] | ||||||||

| Approximant | *w [w] | *y [j] | *l [l] | |||||||

| Nasal | *m [m] | *n [n] | ||||||||

| ||||||||||

The fricatives *s *z *ṣ *ś *ṣ́ *ṯ̣ may also be interpreted as affricates (/t͡s d͡z t͡sʼ t͡ɬ t͡ɬʼ t͡θʼ/), as is discussed below.

The Proto-Semitic consonant system is based on triads of related voiceless, voiced and "emphatic" consonants. Five such triads are reconstructed in Proto-Semitic:

- Dental stops *d *t *ṭ

- Velar stops *g *k *ḳ (normally written *g *k *q)

- Dental sibilants *z *s *ṣ

- Interdental /ð θ θʼ/ (written *ḏ *ṯ *ṯ̣)

- Lateral /l ɬ ɬʼ/ (normally written *l *ś *ṣ́)

The probable phonetic realization of most consonants is straightforward and is indicated in the table with the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). Two subsets of consonants, however, deserve further comment.

Emphatics

The sounds notated here as "emphatic consonants" occur in nearly all Semitic languages as well as in most other Afroasiatic languages, and they are generally reconstructed as glottalization in Proto-Semitic.[16][17][nb 1] Thus, *ṭ, for example, represents [tʼ]. See below for the fricatives/affricates.

In modern Semitic languages, emphatics are variously realized as pharyngealized (Arabic, Aramaic, Tiberian Hebrew (such as [tˤ]), glottalized (Ethiopian Semitic languages, Modern South Arabian languages, such as [tʼ]), or as tenuis consonants (Turoyo language of Tur Abdin such as [t˭]);[18] Ashkenazi Hebrew and Maltese are exceptions and emphatics merge into plain consonants in various ways under the influence of Indo-European languages (Sicilian for Maltese, Yiddish for Hebrew).

An emphatic labial *ṗ occurs in some Semitic languages, but it is unclear whether it was a phoneme in Proto-Semitic.

- Hebrew developed an emphatic labial phoneme ṗ to represent unaspirated /p/ in Iranian and Greek.[19]

- The classical Ethiopian Semitic language Geʽez is unique among Semitic languages for contrasting all three of /p/, /f/, and /pʼ/. While /p/ and /pʼ/ occur mostly in loanwords (especially from Greek), there are many other occurrences whose origin is less clear (such as hepʼä 'strike', häppälä 'wash clothes').[20]

Fricatives

The reconstruction of Proto-Semitic has nine fricative sounds that are reflected usually as sibilants in later languages, but whether all were already sibilants in Proto-Semitic is debated:

- Two voiced fricatives that *ð, *z eventually became, for example, /z/ for both in Hebrew and Geʽez(/ð/ in early Geʽez), but /ð/ and /z/ in Arabic respectively

- Four voiceless fricatives

- *θ (*ṯ) that became /ʃ/ in Hebrew but /θ/ in Arabic and /s/ in Geʽez(/θ/ in early Geʽez)

- *š (*s₁) that became /ʃ/ in Hebrew but /s/ in Arabic and Geʽez

- *ś (*s₂) that became /s/ (transcribed ś) in Hebrew but /ʃ/ in Arabic and /ɬ/ in Geʽez

- *s (*s₃) that became /s/ in Hebrew, Arabic and Geʽez

- Three emphatic fricatives (*θ̣, *ṣ, *ṣ́)

The precise sound of the Proto-Semitic fricatives, notably of *š, *ś, *s and *ṣ, remains a perplexing problem, and there are various systems of notation to describe them. The notation given here is traditional and is based on their pronunciation in Hebrew, which has traditionally been extrapolated to Proto-Semitic. The notation *s₁, *s₂, *s₃ is found primarily in the literature on Old South Arabian, but more recently, it has been used by some authors to discuss Proto-Semitic to express a noncommittal view of the pronunciation of the sounds. However, the older transcription remains predominant in most literature, often even among scholars who either disagree with the traditional interpretation or remain noncommittal.[21]

The traditional view, as expressed in the conventional transcription and still maintained by some of the authors in the field[22][23][24] is that *š was a voiceless postalveolar fricative ([ʃ]), *s was a voiceless alveolar sibilant ([s]) and *ś was a voiceless alveolar lateral fricative ([ɬ]). Accordingly, *ṣ is seen as an emphatic version of *s ([sʼ]) *z as a voiced version of it ([z]) and *ṣ́ as an emphatic version of *ś ([ɬʼ]). The reconstruction of *ś ṣ́ as lateral fricatives (or affricates) is certain although few modern languages preserve the sounds. The pronunciation of *ś ṣ́ as [ɬ ɬʼ] is still maintained in the Modern South Arabian languages (such as Mehri), and evidence of a former lateral pronunciation is evident in a number of other languages. For example, Biblical Hebrew baśam was borrowed into Ancient Greek as balsamon (hence English "balsam"), and the 8th-century Arab grammarian Sibawayh explicitly described the Arabic descendant of *ṣ́, now pronounced [dˤ] in the standard pronunciation or [ðˤ] in Bedouin-influenced dialects, as a pharyngealized voiced lateral fricative [ɮˤ].[25][26] (Compare Spanish alcalde, from Andalusian Arabic اَلْقَاضِي al-qāḍī "judge".)

The primary disagreements concern whether the sounds were actually fricatives in Proto-Semitic or whether some were affricates and whether the sound designated *š was pronounced [ʃ] (or similar) in Proto-Semitic, as the traditional view posits, or had the value of [s]. The issue of the nature of the "emphatic" consonants, discussed above, is partly related (but partly orthogonal) to the issues here as well.

With respect to the traditional view, there are two dimensions of "minimal" and "maximal" modifications made:

- In how many sounds are taken to be affricates. The "minimal affricate" position takes only the emphatic *ṣ as an affricate [t͡sʼ]. The "maximal affricate" position additionally posits that *s *z were actually affricates [t͡s d͡z] while *š was actually a simple fricative [s].[27]

- In whether to extend the affricate interpretation to the interdentals and laterals. The "minimal extension" position assumes that only the sibilants were affricates, and the other "fricatives" were in fact all fricatives, but the maximal update extends the same interpretation to the other sounds. Typically, that means that the "minimal affricate, maximal extension" position takes all and only the emphatics are taken as affricates: emphatic *ṣ θ̣ ṣ́ were [t͡sʼ t͡θʼ t͡ɬʼ]. The "maximal affricate, maximal extension" position assumes not only the "maximal affricate" position for sibilants but also that non-emphatic *θ ð ś were actually affricates.

Affricates in Proto-Semitic were proposed early on but met little acceptance until the work of Alice Faber (1981) who challenged the older approach. The Semitic languages that have survived often have fricatives for these consonants. However, Ethiopic languages and Modern Hebrew, in many reading traditions, have an affricate for *ṣ.[28]

The evidence for the various affricate interpretations of the sibilants is direct evidence from transcriptions and structural evidence. However, the evidence for the "maximal extension" positions that extend affricate interpretations to non-sibilant "fricatives" is largely structural because of both the relative rarity of the interdentals and lateral obstruents among the attested Semitic language and the even-greater rarity of such sounds among the various languages in which Semitic words were transcribed. As a result, even when the sounds were transcribed, the resulting transcriptions may be difficult to interpret clearly.

The narrowest affricate view (only *ṣ was an affricate [t͡sʼ]) is the most accepted one.[29] The affricate pronunciation is directly attested in the modern Ethiopic languages and Modern Hebrew, as mentioned above, but also in ancient transcriptions of numerous Semitic languages in various other languages:

- Transcriptions of Ge'ez from the period of the Axumite Kingdom (early centuries AD): ṣəyāmo rendered as Greek τζιαμω tziamō.[29]

- The Hebrew reading tradition of ṣ as [t͡s] clearly goes back at least to medieval times, as shown by the use of Hebrew צ (ṣ) to represent affricates in early New Persian, Old Osmanli Turkic, Middle High German etc. Similarly, Old French c /t͡s/ was used to transliterate צ: Hebrew ṣɛdɛḳ "righteousness" and ʼārɛṣ "land (of Israel)" were written cedek, arec.[29]

- There is also evidence of an affricate in Ancient Hebrew and Phoenician ṣ. Punic ṣ was often transcribed as ts or t in Latin and Greek or occasionally Greek ks; correspondingly, Egyptian names and loanwords in Hebrew and Phoenician use ṣ to represent the Egyptian palatal affricate ḏ (conventionally described as voiced [d͡ʒ] but possibly instead an unvoiced ejective [t͡ʃʼ]).[30]

- Aramaic and Syriac had an affricated realization of *ṣ until some point, as is seen in Classical Armenian loanwords: Aramaic צרר 'bundle, bunch' → Classical Armenian crar /t͡sɹaɹ/.[31]

The "maximal affricate" view, applied only to sibilants, also has transcriptional evidence. According to Kogan, the affricate interpretation of Akkadian s z ṣ is generally accepted.[32]

- Akkadian cuneiform, as adapted for writing various other languages, used the z- signs to represent affricates. Examples include /ts/ in Hittite,[31] Egyptian affricate ṯ in the Amarna letters and the Old Iranian affricates /t͡ʃ d͡ʒ/ in Elamite.[33]

- Egyptian transcriptions of early Canaanite words with *z, *s, *ṣ use affricates (ṯ for *s, ḏ *z, *ṣ).[34]

- West Semitic loanwords in the "older stratum" of Armenian reflect *s *z as affricates /t͡sʰ/, /d͡z/.[28]

- Greek borrowing of Phoenician 𐤔 *š to represent /s/ (compare Greek Σ), and 𐤎 *s to represent /ks/ (compare Greek Ξ) is difficult to explain if *s then had the value [s] in Phoenician, but it is quite easy to explain if it actually had the value [t͡s] (even more so if *š had the value [s]).[35]

- Similarly, Phoenician uses 𐤔 *š to represent sibilant fricatives in other languages rather than 𐤎 *s until the mid-3rd century BC, which has been taken by Friedrich/Röllig 1999 (pp. 27–28)[36] as evidence of an affricate pronunciation in Phoenician until then. On the other hand, Egyptian starts using s in place of earlier ṯ to represent Canaanite s around 1000 BC. As a result, Kogan[37] assumes a much earlier loss of affricates in Phoenician, and he assumes that the foreign sibilant fricatives in question had a sound closer to [ʃ] than [s]. (A similar interpretation for at least Latin s has been proposed[38] by various linguists based on evidence of similar pronunciations of written s in a number of early medieval Romance languages; a technical term for this "intermediate" sibilant is voiceless alveolar retracted sibilant.)

There is also a good deal of internal evidence in early Akkadian for affricate realizations of s z ṣ. Examples are that underlying ||*t, *d, *ṭ + *š|| were realized as ss, which is more natural if the law was phonetically ||*t, *d, *ṭ + *s|| → [tt͡s],[31] and that *s *z *ṣ shift to *š before *t, which is more naturally interpreted as deaffrication.[32]

Evidence for *š as /s/ also exists but is somewhat less clear. It has been suggested that it is cross-linguistically rare for languages with a single sibilant fricative to have [ʃ] as the sound and that [s] is more likely.[35] Similarly, the use of Phoenician 𐤔 *š, as the source of Greek Σ s, seems easiest to explain if the phoneme had the sound of [s] at the time. The occurrence of [ʃ] for *š in a number of separate modern Semitic languages (such as Neo-Aramaic, Modern South Arabian, most Biblical Hebrew reading traditions) and Old Babylonian Akkadian is then suggested to result from a push-type chain shift, and the change from [t͡s] to [s] "pushes" [s] out of the way to [ʃ] in the languages in question, and a merger of the two to [s] occurs in various other languages such as Arabic and Ethiopian Semitic.

On the other hand, it has been suggested that the initial merged s in Arabic was actually a "hissing-hushing sibilant",[39] presumably something like [ɕ] (or a "retracted sibilant"), which did not become [s] until later. That would suggest a value closer to [ɕ] (or a "retracted sibilant") or [ʃ] for Proto-Semitic *š since [t͡s] and [s] would almost certainly merge directly to [s]. Furthermore, there is various evidence to suggest that the sound [ʃ] for *š existed while *s was still [ts].[40] Examples are the Southern Old Babylonian form of Akkadian, which evidently had [ʃ] along with [t͡s] as well as Egyptian transcriptions of early Canaanite words in which *š s are rendered as š ṯ. (ṯ is an affricate [t͡ʃ] and the consensus interpretation of š is [ʃ], as in Modern Coptic.[40])

Diem (1974) suggested that the Canaanite sound change of *θ → *š would be more natural if *š was [s] than if it was [ʃ]. However, Kogan argues that, because *s was [ts] at the time, the change from *θ to *š is the most likely merger, regardless of the exact pronunciation of *š while the shift was underway.[41]

Evidence for the affricate nature of the non-sibilants is based mostly on internal considerations. Ejective fricatives are quite rare cross-linguistically, and when a language has such sounds, it nearly always has [sʼ] so if *ṣ was actually affricate [tsʼ], it would be extremely unusual if *θ̣ ṣ́ was fricative [θʼ ɬʼ] rather than affricate [t͡θʼ t͡ɬʼ]. According to Rodinson (1981) and Weninger (1998), the Greek placename Mátlia, with tl used to render Ge'ez ḍ (Proto-Semitic *ṣ́), is "clear proof" that this sound was affricated in Ge'ez and quite possibly in Proto-Semitic as well.[42]

The evidence for the most maximal interpretation, with all the interdentals and lateral obstruents being affricates, appears to be mostly structural: the system would be more symmetric if reconstructed that way.

The shift of *š to h occurred in most Semitic languages (other than Akkadian, Minaian, Qatabanian) in grammatical and pronominal morphemes, and it is unclear whether reduction of *š began in a daughter proto-language or in Proto-Semitic itself. Some thus suggest that weakened *š̠ may have been a separate phoneme in Proto-Semitic.[43]

Correspondence of sounds with daughter languages

See Semitic languages#Phonology for a fuller discussion of the outcomes of the Proto-Semitic sounds in the various daughter languages.

Correspondence of sounds with other Afroasiatic languages

See table at Proto-Afroasiatic language#Consonant correspondences.

Grammar

Pronouns

Like most of its daughter languages, Proto-Semitic has one free pronoun set, and case-marked bound sets of enclitic pronouns. Genitive case and accusative case are only distinguished in the first person.[44]

| independent nominative |

enclitic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nominative | genitive | accusative | ||

| 1.sg. | ʼanā̆/ʼanākū̆ | -kū̆ | -ī/-ya | -nī |

| 2.sg.masc. | ʼantā̆ | -tā̆ | -kā̆ | |

| 2.sg.fem. | ʼantī̆ | -tī̆ | -kī̆ | |

| 3.sg.masc. | šuʼa | -a | -šū̆ | |

| 3.sg.fem. | šiʼa | -at | -šā̆/-šī̆ | |

| 1.du. | ? | -nuyā ? | -niyā ? | -nayā ? |

| 2.du. | ʼantumā | -tumā | -kumā/-kumay | |

| 3.du. | šumā | -ā | -šumā/-šumay | |

| 1.pl. | niḥnū̆ | -nū̆ | -nī̆ | -nā̆ |

| 2.pl.masc. | ʼantum | -tum | -kum | |

| 2.pl.fem. | ʼantin | -tin | -kin | |

| 3.pl.masc. | šum/šumū | -ū | -šum | |

| 3.pl.fem. | šin/šinnā | -ā | -šin | |

For many pronouns, the final vowel is reconstructed with long and short positional variants; this is conventionally indicated by a combined macron and breve on the vowel (e.g. ā̆).

Comparative vocabulary and reconstructed roots

See List of Proto-Semitic stems (appendix in Wiktionary).

See also

- Afroasiatic language

- Afroasiatic Urheimat

- Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples

- Prehistory of the Middle East

- Proto-Afroasiatic language

- Proto-Indo-European language

Notes

- That explains the lack of voicing distinction in the emphatic series, which would be unnecessary if the emphatics were pharyngealized.

References

- Kitchen, A.; Ehret, C.; Assefa, S.; Mulligan, C. J. (29 April 2009). "Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of Semitic languages identifies an Early Bronze Age origin of Semitic in the Near East". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1668): 2703–10. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0408. PMC 2839953. PMID 19403539.

- Steiner, Richard C. (2011). Early Northwest Semitic Serpent Spells in the Pyramid Texts. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns.

- Huehnergard, John (2020). "The Languages of the Ancient Near East". In Daniel C. Snell (ed.). A Companion to the Ancient Near East (Second ed.). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 341–353.

- Lipiński 2001, pp. 42

- Ehret, C.; Keita, S.O.Y.; Newman, Paul (3 December 2004). "The Origins of Afroasiatic" (PDF). Science. 306 (5702): 1680. doi:10.1126/science.306.5702.1680c. PMID 15576591. S2CID 8057990.

- Dziebel, German (2007). The Genius of Kinship: The Phenomenon of Human Kinship and the Global Diversity of Kinship Terminologies. Cambria Press. p. 366. ISBN 978-1-934043-65-3. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- Nöth, Winfried (1 January 1994). Origins of Semiosis: Sign Evolution in Nature and Culture. Walter de Gruyter. p. 293. ISBN 978-3-11-087750-2. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- Quantitative Approaches to Linguistic Diversity: Commemorating the Centenary of the Birth of Morris Swadesh. p. 73.

- Lipiński 2001, pp. 43

- Lipiński 2001, pp. 44

- Huehnergard (2008), p. 231.

- Kogan (2011), p. 119.

- Versteegh, Cornelis Henricus Maria "Kees" (1997). The Arabic Language. Columbia University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-231-11152-2.

- Sáenz Badillos, Angel (1993) [1988]. "Hebrew in the context of the Semitic Languages". Historia de la Lengua Hebrea [A History of the Hebrew Language]. Translated by John Elwolde. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0-521-55634-1.

- Kogan (2011), p. 54.

- Cantineau, J. (1952). "Le consonantisme du sémitique". Semitica: 79–94.

- Kogan (2011), p. 61.

- Dolgopolsky 1999, p. 29.

- Hetzron 1997, p. 147.

- Woodard 2008, p. 219.

- For an example of an author using the traditional symbols but subscribing to the new sound values, see Hackett, Joe Ann. 2008. Phoenician and Punic. The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia (ed. Roger D. Woodard). Likewise, Huehnergard, John and Christopher Woods. 2008. Akkadian and Eblaite. The Ancient Languages of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Aksum (ed. Roger D. Woodard). p. 96: "Similarly, there was a triad of affricates, voiced /ᵈz/ (⟨z⟩) voiceless /ᵗs/ (⟨s⟩), and emphatic /ᵗsʼ/ (⟨*ṣ⟩). These became fricatives in later dialects; the voiceless member of this later, fricative set was pronounced [s] in Babylonian, but [š] in Assyrian, while the reflex of Proto-Semitic *š, which was probably simple [s] originally, continued to be pronounced as such in Assyrian, but as [š] in Babylonian." Similarly, an author remaining undecided regarding the sound values of the sibilants will also use the conventional symbols, for example, Greenberg, Joseph, The Patterning of Root Morphemes in Semitic. 1990. p. 379. On language: selected writings of Joseph H. Greenberg. Ed. Keith M. Denning and Suzanne Kemme: "There is great uncertainty regarding the phonetic values of s, ś, and š in Proto-Semitic. I simply use them here as conventional transcriptions of the three sibilants corresponding to the sounds indicated by samekh, śin, and šin respectively in Hebrew orthography."

- Lipiński, Edward. 2000. Semitic languages: outline of a comparative grammar. e.g. the tables on p.113, p.131; also p.133: "Common Semitic or Proto-Semitic has a voiceless fricative prepalatal or palato-alevolar š, i.e. [ʃ] ...", p.129 ff.

- Macdonald, M.C.A. 2008. Ancient North Arabian. In: The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia (ed. Roger D. Woodard). p. 190.

- Blau, Joshua (2010). Phonology and Morphology of Biblical Hebrew. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. p. 25–40.

- Ferguson, Charles (1959), "The Arabic Koine", Language, 35 (4): 630, doi:10.2307/410601, JSTOR 410601.

- Versteegh, Kees (1997), The Arabic Language, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 90-04-17702-7

- For example, Huehnergard (2008), pp. 229–231.

- Dolgopolsky 1999, p. 33.

- Kogan (2011), p. 62.

- Kogan (2011), p. 63.

- Dolgopolsky 1999, p. 32.

- Kogan (2011), p. 66.

- Kogan (2011), p. 67.

- Kogan (2011), pp. 67–68.

- Kogan (2011), p. 69.

- Quoted in Kogan (2011), p. 68.

- Kogan (2011), p. 68.

- Vijūnas, Aurelijus (2010), "The Proto-Indo-European Sibilant */s/", Historische Sprachforschung, Göttingen, 123: 40–55, doi:10.13109/hisp.2010.123.1.40, ISSN 0935-3518

- Kogan (2011), p. 70, quoting Martinet 1953 p. 73 and Murtonen 1966 p. 138.

- Kogan (2011), p. 70.

- Kogan (2011), pp. 92–93.

- Kogan (2011), p. 80.

- Dolgopolsky 1999, pp. 19, 69-70

- Huehnergard (2008), p. 237; Huehnergard's phonetic transcription is changed to traditional symbols here.

Sources

- Blench, Roger (2006). Archaeology, Language, and the African Past. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 978-0-7591-0466-2. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- Dolgopolsky, Aron (1999). From Proto-Semitic to Hebrew. Milan: Centro Studi Camito-Semitici di Milano.

- Hetzron; Robert (1997). The Semitic languages. Cambridge University Press. p. 572. ISBN 0-415-05767-1.

- Huehnergard, John (2000). "Proto-Semitic Language and Culture + Appendix II: Semitic Roots". American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Fourth ed.). Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 2056–2068. ISBN 0-395-82517-2.

- Huehnergard, John. (2003) "Akkadian ḫ and West Semitic ḥ." Studia Semitica 3, ed. Leonid E. Kogan & Alexander Militarev. Moscow: Russian State University for the Humanities. pp. 102–119. ISBN 978-5-728-10690-6

- Huehnergard, John (2008). "Appendix 1. Afro-Asiatic". In Woodard, Roger (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 225–246. ISBN 978-0-521-68498-9.

- Kienast, Burkhart. (2001). Historische semitische Sprachwissenschaft.

- Kogan, Leonid (2011). "Proto-Semitic Phonology and Phonetics". In Weninger, Stefan (ed.). The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 54–151. ISBN 978-3-11-025158-6.

- Lipiński, Edward (2001). Semitic Languages: Outline of a Comparative Grammar. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-0815-4. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- Woodard, Roger (2008). The Ancient Languages of Mesopotamia, Egypt and Aksum. Cambridge University Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-521-68497-2.