Ptychodus

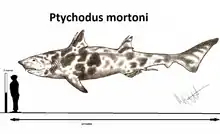

Ptychodus is a genus of extinct sharks.[1] As well as a genus of durophagous (shell-crushing) sharks from the Late Cretaceous.[2] Fossils of Ptychodus teeth are found in many Late Cretaceous marine sediments.[3] There are many species among the Ptychodus that have been uncovered on all the continents around the globe.[3] Such species are Ptychodus mortoni, P. decurrens, P. marginalis, P. mammillaris, P. rugosus and P. latissimus to name a few. They died out approximately 85 million years ago in the Western Interior Sea, where a majority of them were found.[2] A recent publication found that Ptychodus are likely neoselachians, rather than hybodonts or batoids as previously thought.[4][5]

| Ptychodus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ptychodus mortoni | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Family: | †Ptychodontidae |

| Genus: | †Ptychodus Agassiz, 1837 |

| Type species | |

| Ptychodus latissimus Agassiz, 1835 | |

| Other species | |

| |

Discovery

Due to a well global distribution the Ptychodus is well represented in the fossil history; many fossils have been uncovered such as isolated teeth, fragments of dentition, calcified vertebral centra, denticles, and associated fragments of calcified cartilage.[6] The very first remains of Ptychodus were found in England and Germany in the first half of the 18th century. [7][8] Ptychodus teeth have long been identified as palates of diodon, or porcupinefish (Osteichthyes, Diodontidae), well-known for their ability to inflate their bodies in defense. At the beginning of the 19th century, several authors including Swiss paleontologist Louis Agassiz eventually demonstrated the affinities of Ptychodus teeth with those of elasmobranchs (rays and sharks). The first discovery of Ptychodus teeth in Kansas came in 1868 when Leidy reported and described a damaged tooth near Fort Hays, Kansas.[9][4] After, many more teeth were uncovered in almost perfect conditions and other species within the genus were identified.[4] Fossils of species within this genus have been found in the marine strata of United States, Brazil, Canada, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, India, Israel, Japan, Jordan, Mexico, Sweden and the United Kingdom.[3] The fact that so many fossils of Ptychodus have been found in different regions of the world provides evidence of a distribution of species during the Albian-Turonian time.[6]

The generic name Ptychodus comes from the Greek words ptychos (fold/layer) and odon (tooth), so "fold teeth" describing the shape of their crushing and grinding teeth that were recovered in deposits around the Niobrara Formation.[10]

Description

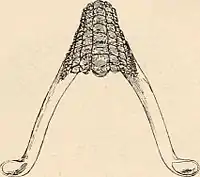

Ptychodus was about 10 meters (33 feet) long.[11] It was covered in placoid scales like other sharks, reinforced with a large cartilaginous skeleton, and was a bearer of large serrated spines along the dorsal fin.[12] Unlike the colossal nektonic planktivores Rhincodon (whale sharks) and Cetorhinus (basking sharks) which relied upon gill rakers to acquire their food, the Ptychodus had a massive arrangement crushing plate teeth. A Ptychodus jaw contains many teeth, up to 550 teeth, 220 of which are on the lower jaw and 260 in the upper jaw. These teeth were very large as well. Paleontologists believe that the largest tooth plate measured 55 centimeters in length and 45 centimeters in width. There are two distinct formations of tooth plate between the genus; one being juxtaposed, non-overlapping tooth rows and another being imbricated tooth rows.[13] It is believed that the shape coincides with the diet of the species and their geographic locations, but the time it lived has a big part as well. Ptychodus marginalis teeth differ from Ptychodus polygyrus. P marginalis was in the Middle Cenomanian to Middle Turonian deposits in the English Chalk, while P. polygyrus were in the Late Santonian-Early Campanian deposits.[14]

Paleobiology

While there is no solid evidence of members of the Ptychodus species living among other durophagous sharks like members of Heterodontidae (bullhead sharks), it is believed that this Cretaceous macropredator was the precursor to crushing plate teeth seen in many similar sharks and rays.[15] Ptychodus would have been a benthic predator, straying from the upper layers of the oceans that would have been inhabited by mosasaurs, pliosaurs, and other sharks such as Cretoxyrhina, which it was ill-equipped to tackle or compete with. It was capable of growing to enormous size because of this, decreasing the contact it had with macropredatory organisms, and securing a vast food source with little to no competition. Its biological range was linked to the Western Interior Seaway, where it was restricted to the middle and southern end, away from the highly concentrated remains of Cretoxyrhina and Squalicorax in the same period. It is believed that Ptychodus species not only preferred this area because of the subtropical environment, but due to the higher concentration of their prey source Cremnoceramus, Volviceramus and other members of the inoceramids.[16]

Diet

Ptychodus was a molluscivore predator that dined upon the extremely large bivalves and crustaceans inhabiting the Western Interior Seaway. The Ptychodus diet was probably restricted to slow-moving or sessile shellfish, mollusks, invertebrates, larvae, and the occasional sunken carrion of Cretaceous megafauna that it could manipulate into its mouth. P. decurrens (found in southern India) ate animals with hard shells.[6] One of the largest bivalves at the time was the 9-foot Platyceramus, a shelled mollusk that would have provided a difficult meal for any other creature, but with its crushing palate Ptychodus could have broken through this durable mollusk with ease.[12] Giant ammonites such as the Parapuzosia seppenradensis, members of the Belemnite family, squid, and a variety of Cretaceous crustaceans would also make up the majority of the shark's food.

Gallery

Ptychodus mammillaris teeth

Ptychodus mammillaris teeth Teeth of Ptychodus decurrens from Cretaceous of United States

Teeth of Ptychodus decurrens from Cretaceous of United States Teeth of Ptychodus sp. from Cretaceous of United States

Teeth of Ptychodus sp. from Cretaceous of United States Teeth attributed to Ptychodus decurrens

Teeth attributed to Ptychodus decurrens Lower jaw of Ptychodus sp.

Lower jaw of Ptychodus sp.

References

- Fossils (Smithsonian Handbooks) by David Ward (Page 200)

- Everhart, Mike. "Ptychodus mortoni". Ocean of Kansas.

- The paleobioloy Database Ptychodus entry accessed on 8/23/09

- Everhart, Michael; Caggiano, Tom. "An associated dentition and calcified vertebral centra of the Late Cretaceous elasmobranch, Ptychodus anonymus Williston 1900". 4 (4): 125–136. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hoffman, Brian (July 2016). "et. al". Journal of Paleontology. 90 (4): 741–762. doi:10.1017/jpa.2016.64.

- Verma, Omkar; et al. (February 1, 2012). "Ptychodus decurrens Agassiz (Elasmobranchii: Ptychodontidae) from the Upper Cretaceous of India". Cretaceous Research. 33 (1): 183–188. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2011.09.014.

- Brignon, A., 2015, Senior synonyms of Ptychodus latissimus Agassiz, 1835 and Ptychodus mammillaris Agassiz, 1835 (Elasmobranchii) based on teeth from the Bohemian Cretaceous Basin (the Czech Republic). Acta Musei Nationalis Pragae, Series B – Historia Naturalis, 71(1–2): 5–14

- Brignon, A., 2019, Le diodon devenu requin : l'histoire des premières découvertes du genre Ptychodus (Chondrichthyes) [The porcupinefish that became a shark: History of the early discoveries of the genus Ptychodus (Chondrichthyes)]. Published by the author, Bourg-la-Reine, France, 100 pp., ISBN : 978-2-9565479-2-1 (printed), 978-2-9565479-3-8 (ebook)

- Everhard, Mike. "Ptychodontid Sharks: Late Cretaceous Shell Crushers". Ocean of Kansas.

- David, Michelle A historical and mechanical description of Ptychodus (Chondrichthyes) dententions with notes on the distribution and systematics of the genus

- "BBC - Earth News - Giant predatory shark fossil unearthed in Kansas"

- A Field Guide to Fossils of the Smoky Hill Chalk

- Shimada, Kenshu (October 31, 2012). "Dentition of Late Cretaceous shark, Ptychodus mortoni (Elasmobranchii, Ptychodontidae)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (6): 1271–1284. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.707997.

- Hamm, Shawn (May 2010). "The Late Cretaceous shark Ptychodus marginalis in the Western Interior Seaway, USA". Journal of Paleontology. 84 (3): 538–548. doi:10.1666/09-154.1.

- Shawn A. Hamm The Late Cretaceous shark, Ptychodus rugosus, (Ptychodontidae) in the Western Interior Sea Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science (1903) - Vol. 113, No. 1/2 (Spring 2010), pp. 44-55

- Shawn Hamm Ptychodus and species 2011 - SYSTEMATIC, STRATIGRAPHIC, GEOGRAPHIC AND PALEOECOLOGICAL DISTRIBUTION OF THE LATE CRETACEOUS SHARK GENUS PTYCHODUS WITHIN THE WESTERN INTERIOR SEAWAY

- Williston, Samuel (1900) University Geological Survey of Kansas, Volume VI: Paleontology part II, (Carboniferous invertebrates and Cretaceous fish)

External links

Media related to Ptychodus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ptychodus at Wikimedia Commons- BBC page on Ptychodus mortoni: "Giant predatory shark fossil unearthed in Kansas"