RML 9-inch 12-ton gun

The RML 9-inch guns Mark I – Mark VI[note 1] were large rifled muzzle-loading guns of the 1860s used as primary armament on smaller British ironclad battleships and secondary armament on larger battleships, and also ashore for coast defence.

| Ordnance RML 9-inch 12-ton gun | |

|---|---|

Restored Mark I, RML 9-inch 12-ton gun being fired at Simon's Town in 2014, with replica ammunition in the foreground | |

| Type | Naval gun Coast defence gun |

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1865–1922 (Mk VI) |

| Used by | Royal Navy Australian Colonies Spanish Navy |

| Wars | Bombardment of Alexandria |

| Production history | |

| Designed | 1865 |

| Manufacturer | Royal Arsenal |

| Unit cost | £740[1] (equivalent to £456,200 in 2013)[2] |

| Variants | Mk I–VI |

| Specifications | |

| Barrel length | 125 inches (3.2 m) (bore)[3] |

| Shell | Mk I–V : 250 to 256 pounds (113.4 to 116.1 kg) Palliser, Common, Shrapnel[4] Mk VI : 360 pounds (163.3 kg) AP[5] |

| Calibre | 9-inch (228.6 mm) |

| Muzzle velocity | 1,420 feet per second (430 m/s)[6] |

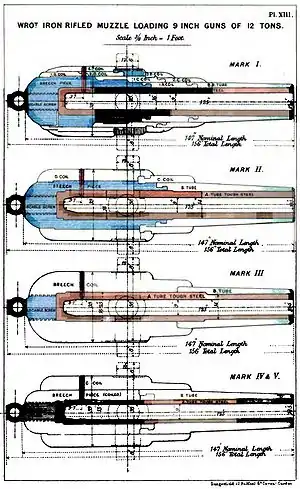

Design

The rifling was the Woolwich pattern of a relatively small number of broad, rounded shallow grooves : there were 6 grooves, increasing from 0 to 1 turn in 45 calibres (i.e. 405 inches).[3]

Mark I, introduced in 1865, incorporated the strong but expensive Armstrong method of a steel A tube surrounded by multiple thin wrought-iron coils which maintained the central A tube under compression,[7] and a forged steel breech-piece. 190 were made.[8]

Mark II in 1866 incorporated the modified Fraser design. This was an economy measure, intended to reduce the costs incurred in building to the Armstrong design. It incorporated fewer but heavier wrought-iron coils but retained the Armstrong forged breech-piece. Only 26 were made.

Mark III in 1866–1867 eliminated the Armstrong forged breech piece and hence fully implemented the Fraser economy design. It consisted of only 4 parts : steel A tube, cascabel, B tube and breech coil. 136 were made.

Mark IV, introduced 1869, and V incorporated a thinner steel A tube and 2 breech coils. The explanation for separating the heavy breech coil of Mk III into a coiled breech piece covered by a breech coil was "the difficulty of ensuring the soundness of the interior of a large mass of iron".[8]

Mk VI high-angle gun

In the late 1880s and early 1890s a small number of guns were adapted as high-angle coast defence guns around Britain : known battery locations were Tregantle Down Battery at Plymouth, Verne High Angle Battery at Portland and Steynewood Battery at Bembridge on the Isle of Wight.

The idea behind these high-angle guns was that the high elevation gave the shell a steep angle of descent and hence enabled it to penetrate the lightly armoured decks of attacking ships rather than their heavily armoured sides. To increase accuracy the old barrels were relined and given modern polygroove rifling : 27 grooves with a twist increasing from 1 turn in 100 calibres to 1 turn in 35 calibres after 49.5 inches. These guns fired a special 360-pound armour-piercing shell to a range of 10,500 yards using a propellant charge of 14 lb Cordite Mk I size 7½, remained in service through World War I and were not declared obsolete until 1922.[9]

Some guns were bored out and relined in 10-inch calibre. A battery of six such guns is known to have been mounted at Spy Glass Battery on the Rock of Gibraltar, and six guns at Gharghur, Malta.

Ammunition

The projectiles of RML 9-inch guns Marks I-V (the Woolwich rifled guns) had several rows of "studs" which engaged with the gun's rifling to impart spin. Sometime after 1878, "attached gas-checks" were fitted to the bases of the studded shells, reducing wear on the guns and improving their range and accuracy. Subsequently, "automatic gas-checks" were developed which could rotate shells, allowing the deployment of a new range of studless ammunition. Thus, any particular gun potentially operated with a mix of studded and studless ammunition. The Mark VI high-angle gun had polygroove rifling, and was only able to fire studless ammunition, using a different automatic gas-check from the one used with Marks I-V.

The gun's primary projectile was Palliser shot or shell, an early armour-piercing projectile for attacking armoured warships. A large battering charge of 50 pounds P (pebble) or 43 pounds R.L.G. (rifle large grain) gunpowder[10] was used for the Palliser projectile to achieve maximum velocity and hence penetrating capability.

Common (i.e. ordinary explosive) shells and shrapnel shells were fired with the standard full service charge of 30 pounds R.L.G. gunpowder or 33 pounds P (pebble) gunpowder,[10] as for these velocity was not as important.

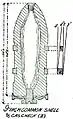

Studded Common shell without gas-check, 1872

Studded common shell with gas-check

Studless common shell with Rotating gas-check

Studless Palliser shell with rotating gas-check

See also

Surviving examples

- Mark I Number 14, dated 1865 on Saint Helena

- Mark I Number 22 at Middle North Battery, Simon's Town, South Africa, and still being fired.

- Mark I Number 127 dated 1867, Castle Field, Wicklow

- Mark I Number 148 dated 1867, Fort St. Catherine, Bermuda

- Mark I guns at Apostles Battery, St Lucia

- Mark III and Mark IV guns Needles Old Battery, Isle of Wight, UK

- A Mark III gun from the Needles Old Battery, now outside Southsea Castle, Portsmouth, UK

- Mark III gun, ex-Needles battery, now at Hurst Castle, Hampshire, UK

- Mark III gun, ex-Needles battery, now at Fort Brockhurst, Hampshire, UK

- Mark III gun, ex-Needles battery, now at Fort Widley, Hampshire, UK

- Mark III Number 272 dated 1868, Alexander battery, St George, Bermuda

- Mark V gun, Harwich Redoubt, Essex, UK

- Mark V gun of 1872 at Whampoa, Kowloon, Hong Kong

- Mark V Number 589, dated 1872 on Saint Helena

- Mark V Number 592 at South Head, Sydney, Australia

- Mark V Number 650, dated 1877 at York Redoubt, Halifax, Canada

- MK I No. 1670 of 1867 at Fort Queenscliff, Victoria, Australia

- No.s 1679 & 1683 at The Strand, Williamstown, Victoria, Australia

- No.s 1669 & 1675 at Fort Gellibrand, Victoria, Australia

- at York Redoubt National Historic Site, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

- A gun at The Citadel, Quebec, Canada

Notes

- Mark I – Mark VI = Mark 1 through to Mark 6. Britain used Roman numerals to denote Marks (models) of ordnance until after World War II. Hence this article describes the six models of RML 9-inch guns.

References

- Unit cost of £739 17 shillings 8 pence is quoted in The British Navy Volume II, 1882, by Sir Thomas Brassey. Page 38

- "Relative worth in 2013: labour cost". Measuring Worth. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- Treatise on Construction of Service Ordnance 1877, page 292

- 250 lb projectile is quoted in 1877 Treatise on Ammunition; 253 lb 5 oz in Text Book of Gunnery 1887; 256 lb in Text Book of Gunnery 1902

- Hogg & Thurston 1972; Text Book of Gunnery 1902

- 1,420 feet/second firing 250-pound projectile with battering charge of 50 pound P (gunpowder). Treatise on Construction of Service Ordnance 1877, page 348

- Holley states that Daniel Treadwell first patented the concept of a central steel tube kept under compression by wrought-iron coils.. and that Armstrong's assertion that he (Armstrong) first used a wrought-iron A-tube and hence did not infringe the patent, was disingenuous, as the main point in Treadwell's patent was the tension exerted by the wrought-iron coils, which Armstrong used in exactly the same fashion. Holley, Treatise on Ordnance and Armour, 1865, pages 863–870

- Treatise on Construction of Service Ordnance 1877, pages 92–93 and 277–280

- Hogg & Thurston 1972, page 158-159

- Treatise on Ammunition 1877, page 220

Bibliography

- Treatise on the construction and manufacture of ordnance in the British service. War Office, UK, 1877

- Text Book of Gunnery, 1887. LONDON : PRINTED FOR HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE, BY HARRISON AND SONS, ST. MARTIN'S LANE

- Text Book of Gunnery, 1902. LONDON : PRINTED FOR HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE, BY HARRISON AND SONS, ST. MARTIN'S LANE

- Treatise on Ammunition. 2nd Edition 1877. War Office, UK.

- Treatise on Ammunition, 4th Edition 1887. War Office, UK.

- Sir Thomas Brassey, The British Navy, Volume II. London: Longmans, Green and Co. 1882

- I.V. Hogg & L.F. Thurston, British Artillery Weapons & Ammunition 1914–1918. London: Ian Allan, 1972.

- Alexander Lyman Holley, A Treatise on Ordnance and Armor published by D Van Nostrand, New York, 1865

- "High Angle Fire Mountings and Batteries" at Victorian Forts website

- " Handbook for the 9-inch rifled muzzle-loading gun of 12-tons Marks I to VIc", 1894, London. Published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to RML 9 inch 12 ton Gun. |

- Diagram of gun on Moncrieff disappearing mounting, at Victorian Forts website

- Diagram of gun on Casemate A Pivot mounting, at Victorian Forts website

- Diagram of gun on C Pivot, at Victorian Forts website

- Diagram of gun on Dwarf A Pivot, at Victorian Forts website

- Diagram of gun on High Angle mounting, at Victorian Forts website