Architecture of Madagascar

The architecture of Madagascar is unique in Africa, bearing strong resemblance to the construction norms and methods of Southern Borneo from which the earliest inhabitants of Madagascar are believed to have immigrated. Throughout Madagascar and the Kalimantan region of Borneo, most traditional houses follow a rectangular rather than round form, and feature a steeply sloped, peaked roof supported by a central pillar.

Differences in the predominant traditional construction materials used serve as the basis for much of the diversity in Malagasy architecture. Locally available plant materials were the earliest materials used and remain the most common among traditional communities. In intermediary zones between the central highlands and humid coastal areas, hybrid variations have developed that use cob and sticks. Wood construction, once common across the island, declined as a growing human population destroyed greater swaths of virgin rainforest for slash and burn agriculture and zebu cattle pasture. The Zafimaniry communities of the central highland montane forests are the only Malagasy ethnic group who have preserved the island's original wooden architectural traditions; their craft was added to the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2003.

As wood became scarce over time, wooden houses became the privilege of the noble class in certain communities, as exemplified by the homes of the Merina nobility in the 19th century Kingdom of Madagascar. The use of stone as a building material was traditionally limited to the construction of tombs, a significant feature of the cultural landscape in Madagascar due to the prominent position occupied by ancestors in Malagasy cosmology. The island has produced several distinct traditions in tomb architecture: among the Mahafaly of the southwest coast, the top of tombs may be stacked with the skulls of sacrificed zebu and spiked with aloalo, decoratively carved tomb posts, while among the Merina, aristocrats historically constructed a small wooden house on top of the tomb to symbolize their andriana status and provide an earthly space to house their ancestors' spirits.

Traditional styles of architecture in Madagascar have been impacted over the past two hundred years by the increasing influence of European styles. A shift toward brick construction in the Highlands began during the reign of Queen Ranavalona II (1868–1883) based on models introduced by missionaries of the London Missionary Society and contacts with other foreigners. Foreign influence further expanded following the collapse of the monarchy and French colonization of the island in 1896. Modernization over the past several decades has increasingly led to the abandonment of certain traditional norms related to the external orientation and internal layout of houses and the use of certain customary building materials, particularly in the Highlands. Among those with means, foreign construction materials and techniques – namely imported concrete, glass and wrought iron features – have gained in popularity, to the detriment of traditional practices.

Origins

The architecture of Madagascar is unique in Africa, bearing strong resemblance to the architecture of southern Borneo from which the earliest inhabitants of Madagascar are believed to have emigrated.[1] Traditional construction in this part of Borneo, also known as South Kalimantan, is distinguished by rectangular houses raised on piles. The roof, which is supported by a central pillar, is steeply sloped; the gable beams cross to form roof horns that may be decoratively carved.[2] The central Highlands of Madagascar are populated by the Merina, peoples who bear strong physiological and cultural resemblance to their Kalimantan ancestors; here, the traditional wooden houses of the aristocracy feature a central pillar (andry) supporting a steeply sloped roof decorated with roof horns (tandro-trano).[3] In the southeast of Madagascar, actual zebu horns were traditionally affixed to the gable peak.[4] Throughout Madagascar, houses are rectangular with a gabled roof as in Kalimantan, central pillars are widespread, and in all but a handful of regions, traditional homes are built on piles in a manner handed down from generation to generation, regardless of whether the feature is suited to local conditions.[5]

Certain cosmological and symbolic elements are common across Indonesian and Malagasy architecture as well.[3][6] The central house pillar is sacred in Kalimantan and Madagascar alike, and in both places, upon constructing a new house this pillar was often traditionally anointed with blood.[2][3] The features of the building or its dimensions (length, size, and particularly the height) are often symbolically indicative of the status of its occupants or the importance of its purpose on both islands.[3][4] Likewise, both Madagascar and Borneo have a tradition of partially above-ground tomb construction[3] and the inhabitants of both islands practice the carving of decorative wooden funerary posts, called aloalo in western Madagascar and klirieng in the Kajang dialect of Borneo.[2]

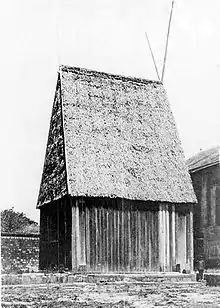

Plant-based construction

Dwellings made of plant material are common in the coastal regions and were once commonly used throughout the Highlands as well.[5] The types of plants available in a given locality determine the building material and style of construction. The vast majority of homes made of plant material are rectangular, low (one-story) houses with a peaked roof and are often built on low stilts.[5] These architectural features are nearly identical to those found in parts of Indonesia.[1] Materials used for construction include reeds (near rivers), rushes (in the southwest around Toliara), endemic succulents (as fencing in the south), wood (in the south and among the Zafimaniry, and formerly common in the Highlands), bamboo (especially in the eastern rain forests), papyrus (formerly in the Highlands around Lake Alaotra), grasses (ubiquitous), palms (ubiquitous but prevalent in the west around Mahajanga) and raffia (especially in the north and northeast).[5] For much of the length of the eastern coast of Madagascar bordering the Indian Ocean, architecture is highly uniform: nearly all traditional homes in this region are built on low stilts and are roofed with thatch made of the fronds of the traveler's palm (ravinala madagascariensis).[5]

The stilts, floor and walls are commonly made of the trunk of this same plant, typically after pounding it flat to make wide planks (for floors and roofing) or narrow strips (for walls). These strips are affixed vertically to the frame; the raffia plant is often used in the same way, in place of the traveler's palm, in the north.[5] When bamboo is used in place of ravinala, the long pounded sheets are often woven together to create walls with a checker-like pattern.[7]

These traditional homes have no chimney. Their floor is covered in a woven mat with stones heaped in one corner where wood fires can be burnt to cook food; the smoke that accumulates blackens the ceiling and interior walls over time.[8] The doorways of these homes were traditionally left open or could be shut by a woven screen held closed with a leather strap;[8] today the entryway is frequently hung with a fabric curtain.[9] Variations on this basic template can be found in all coastal regions using locally available material.[5] The largest of the traditional coastal houses are found in the southeast among the Antemoro, Tanala and Antefasy peoples, where homes can reach 18' long, 9' wide and 15' high. Elsewhere along the coast homes are much smaller, averaging 10' long, 8' wide and 9' high.[5]

Wood-based construction

It is believed that wood construction was formerly common in many parts of Madagascar but it has all but disappeared due to deforestation.[10] This is especially true in the Highlands where, until recently, wood had been a building material reserved for the aristocratic class due to its increasing rarity, leaving the lower classes to construct in other locally available materials such as reeds and grasses; sticks and branches are occasionally used where available, creating sporadic villages of wood typically within proximity to forest reserves.[5] While the wooden architectural tradition among the aristocracy of the Merina has died out,[3] at least two ethnic groups can be said to have a continuing tradition of plank wood architecture: the Zafimaniry in the central Highlands, and the Antandroy in the far south. Each of these three traditions is described below.[5]

Merina aristocratic tradition

Among the Merina of the central Highlands, the Temanambondro (Antaisaka) people of the southeastern Manambondro region, and several other ethnic groups, deforestation rendered wood a valuable construction material only to be used by aristocrats.[4][10] Indeed, its traditional association with the royal andriana class led King Andrianampoinimerina (1787–1810) to issue a royal edict forbidding construction in stone, brick or earth within the limits of Antananarivo[5] and codifying a tradition in which only the houses of nobles were constructed from wood, while those of peasants were made from local plant materials.[11] This tradition historically existed among a number of ethnic groups in Madagascar, particularly along the eastern coast where the preservation of rainforests continues to facilitate access to wood for construction.[4]

Traditional peasants' houses throughout Imerina featured a thick central pillar (andry) that supported the roof beam and a smaller upright beam at each corner extending into the ground to stabilize the structure.[3] Unlike most coastal houses, Highland homes have never been raised on stilts but have always sat flush to the ground.[5] To the south of the central pillar, in the area designated for sleeping and cooking, wooden or bamboo planks were occasionally installed for flooring, or woven mats were laid on the packed earth floor, which extended north past the pillar. Traditionally, the bed of the head of the family was in the southeast corner of the house.[3] The northern area was distinguished by the hearth, delineated by three oblong stones set vertically into the ground. Houses and tombs were aligned on a north-south axis with the entrance on the west face.[12] The north portion of the house was reserved for males and guests, while the south was for women, children and those of inferior rank. The northeast corner was sacred, reserved for prayer and offerings of tribute to the ancestors.[12]

The houses of the nobles were constructed according to these same cultural norms, with several additions.[12] They were distinguishable from the outside by their walls made of upright wooden planks and the long wooden horns (tandrotrano) formed by the crossing of the roof beams at each end of the roof peak. The length of the tandrotrano was indicative of rank: the longer the length, the higher the status of the noble family that lived within.[11] The interior of the building was also somewhat modified, often featuring three central pillars rather than one and occasionally a wooden platform bed raised high off the ground.[12]

After Andrianampoinimerina's edicts regarding construction materials in the capital were revoked in the late 1860s,[11] wooden construction was all but abandoned in Imerina and older wooden houses were rapidly replaced with new brick homes inspired by LMS missionaries' British-style dwellings.[10] The tandrotrano horns were gradually replaced by a simple decorative finial installed at the two ends of the roof peak.[5] Other architectural norms such as the north-south orientation, central pillar and interior layout of homes were abandoned, and the presence of finials on roof peaks is no longer indicative of a particular social class.[12] Classic examples of Highland wooden architecture of the aristocratic class were preserved in the buildings of the Rova compound of Antananarivo (destroyed in a fire in 1995 but under reconstruction)[13] and the walled compound at Ambohimanga, location of the wooden palaces of King Andrianampoinimerina and Queen Ranavalona I. Ambohimanga, arguably the most culturally significant remaining example of the wooden architecture of the Highlands aristocracy, was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2001.[14]

Zafimaniry traditions

The Zafimaniry inhabit the heavily forested, rainy and temperate region of the Highlands to the east of Ambositra. Their homes are rectangular and large (15' long, 12' wide and 18' high) with a peaked roof, overhanging eaves, and wooden windows and doors.[5] Many of the same standards found in the aristocratic architectural traditions of Imerina are present in the Zafimaniry structures, including the central wooden pillar supporting the roof beam, exclusive use of a tongue and groove joining technique and the orientation of building features such as windows, doors and the interior layout.[15] Zafimaniry houses are often elaborately decorated with carved, symmetrical, abstract patterns that are rich in complex spiritual and mythological symbolism.[15] The architecture of the houses found in this region are considered to be representative of the architectural style that predominated throughout the Highlands prior to deforestation, and as such, they represent the last vestiges of a historic tradition and a significant element of Malagasy cultural heritage. For this reason, the woodcrafting knowledge of the Zafimaniry was added in 2003 to the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.[15]

Antandroy traditions

By contrast, the Antandroy inhabit the Madagascar spiny thickets, an extremely dry and hot region in the south of Madagascar where unique forms of drought-resistant plants have evolved and thrived. Their homes are traditionally square (not rectangular), raised on low stilts, topped with a peaked roof and constructed of vertically-hung planks of wood affixed to a wooden frame.[5] These homes traditionally had no windows and featured three wooden doors: the front door was the women's entrance, the door at the rear of the house was for children, and the third door was used by the men.[8] Fences are often constructed around Antandroy houses using prickly-pear cactus (raketa) or lengths of indigenous succulents from the surrounding spiny forests.[16]

Earth-based construction

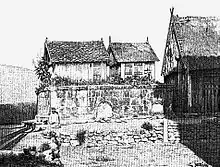

In the central Highlands, power struggles between the Merina and vazimba principalities and later amongst Merina principalities over the centuries inspired the development of the fortified town in Imerina, the central region of the Highlands of Madagascar.[17] The first of these, the ancient Imerina capital of Alasora, was fortified by 16th-century king Andriamanelo, who surrounded the town with thick cob walls (tamboho, made from the mud and dry rice stalks gathered from nearby paddies) and deep trenches (hadivory) to protect the dwellings inside.[18] The entryway through the town wall was protected by an enormous stone disk (vavahady) – five feet in diameter or more – shaded by fig trees (aviavy) symbolic of royalty.[19] The town gate was opened by laboriously rolling the vavahady away from the entryway each morning and back into place again in the evening, a task that required a team of men to accomplish it.[20] This fortified town model was adopted throughout Imerina[19] and is well represented at the historic village of Ambohimanga.[21]

Foreign influences

Protestant Missionary James Cameron of the London Missionary Society is believed to have been the first in Madagascar to demonstrate how local cob building material could be used to create sun-dried bricks in 1826.[22] In 1831, Jean Laborde introduced brick roof tiles that soon began replacing rice stalk thatch in Antananarivo and the surrounding areas, and disseminated the technique of using a kiln to bake bricks.[5]

Foreigners were responsible for several architectural innovations that blended the traditions of Highlands architecture with European sensibilities.[12] In 1819, Louis Gros designed the Tranovola for Radama I in the Rova complex, introducing the wraparound veranda supported by exterior columns. Jean Laborde designed the Queen's Palace in the Rova (built 1839–1841) using this same model on an even grander scale by enlarging the building and adding a third-story veranda.[12] The new wooden buildings constructed by Gros and Laborde transformed the tandrotrano of traditional aristocratic Merina homes into the a decoratively carved post affixed at each end of the gable peak.[5]

Local innovations

In 1867, restrictions were relaxed on the aristocracy's use of stone and brick as building materials, before all restrictions on construction were abolished in 1869 by Queen Ranavalona II, who had already commissioned Jean Laborde in 1860 to encase the exterior of her wooden palace at the Rova in stone. The building took its final form in 1872 after James Cameron added stone towers to each corner of the palace.[12] The queen converted to Christianity in 1869 and that same year the London Missionary Society commissioned James Cameron to construct a private home for its missionaries. He drew his inspiration from the work of Gros and Laborde to develop a multi-story wooden house with veranda and columns.[5] This model exploded in popularity throughout Antananarivo and surrounding areas as an architectural style for the aristocracy, who had to that point continued to inhabit simple homes similar to the wooden palace of Andrianampoinimerina at Ambohimanga. These newly favored brick houses often featured shortened tandrotrano and elaborately carved verandas.[12] These homes can naturally range in color from deep red to almost white depending on the characteristics of the earth used in its construction.[20]

Over time, and particularly with the colonization of Madagascar by the French, these earthen houses (known as trano gasy – "Malagasy house") underwent constant evolution.[23] The simplest form of earthen house is one or more stories tall, rectangular, and features a thatched roof with slightly overhanging eaves to direct rain away from the foundation and thereby prevent its erosion. Wealthier families replace the thatch with clay roofing tiles and construct a veranda on the west face of the building supported by four slender equidistant columns; this design is even more effective at protecting the building's foundations from the eroding effects of rainfall.[5] Further expansion often entails the enclosure of the western veranda in wood and the construction of an open veranda on the eastern face of the building, and so forth, leading to wrap-around verandas, the connection of two separate buildings with a covered passage, the incorporation of French wrought-iron grills or glass panels into verandas, the application of painted concrete over the brick surface and other innovations.[23] In suburban and rural zones, the ground floor of the trano gasy is often reserved as a pen for livestock, while the family inhabits the upper floors.[24] The entrance typically faces west; the kitchen is often to the south, while the family sleeps in the northern part of the building. This configuration is consistent with that seen in the traditional Zafimaniry houses and reflects traditional cosmology.[3]

Mixed cob construction

On the eastern side of Madagascar, there is virtually no zone of transition between the earthen houses of the Highlands and the dwellings made of plant materials common to the coastal regions. In the vast and sparsely populated expanses between the Highlands and the western coastal areas, however, inhabitants utilize locally available materials to construct dwellings that bear features of both regions.[5] Most often houses are small – one room and only one story high – constructed of a skeleton of horizontally arranged sticks affixed to the wooden house frame as pictured in the preceding section on wooden construction. But unlike coastal homes where this stick skeleton would serve as a base for affixing plant material to form walls, earthen cob may be packed into the framework instead. The roof is thatched to complete the dwelling. These intermediary houses are also often distinguished by the presence of shortened Highlands-style wooden columns on the western face to support the elongated eave of the peaked roof, much as they support the verandas of the larger homes of Imerina. The floor is typically packed dirt and may be covered with woven mats of grasses or raffia.[5]

Tomb construction

According to the traditional beliefs of many Malagasy ethnic groups, one attains the status of "ancestor" after death.[17] It is often believed that ancestors continue to watch over and shape events on Earth and can intervene on behalf of (or interfere with) the living. As a consequence, ancestors are to be revered: prayers and sacrifices to honor or appease them are common, as well as the observation of the local fady (taboos) the ancestors may have established in life. Gestures of respect, such as throwing the first capful of a new bottle of rum into the northeast corner of the room to share it with the ancestors, are practiced throughout the island.[12] The most visible emblem of the respect due to ancestors is the construction of the elaborate family tombs that dot the countryside in much of Madagascar.[25]

Earliest burial practices

Traditionally, the majority of Malagasy ethnic groups did not construct solid tombs for their dead. Rather, the bodies of the deceased were left in a designated natural area to decompose. Among the Bara people of the southern arid plains, for instance, tombs may be built into natural features such as rock outcroppings or hillsides by placing the bodies within and partially or entirely sealing the space with stacked stones or zebu skulls. Alternately, among the Tanala, the deceased may be placed in coffins made from hollowed-out logs and left in caves or a sacred grove of trees, sometimes covered over by wooden planks held down by small piles of stones.[17] It is said the Vazimba, the earliest inhabitants of Madagascar, submerged their dead in the waters of a designated bog, river, lake or estuary, which was thereby considered sacred for that purpose.[8] The practice also existed among the earliest Merina, who submerged their dead chiefs in canoes into Highland bogs or other designated waters.[16] Where tombs were built, minor variation in form and placement from one ethnic group to the next is overshadowed by common features: the structure is partially or fully subterranean, typically rectangular in design and made of stone that is either stacked loosely or cemented with masonry. Among the Merina and Betsileo, some early stone tombs and burial sites were indicated by upright, unmarked standing stones.[5]

Islamic origins of tomb construction

The earliest known rectangular stone tombs on Madagascar were most likely built by Arab settlers around the 14th century in the northwestern part of the island.[26] Similar models emerged later among western (i.e. Sakalava, Mahafaly) and highlands (i.e. Merina, Betsileo) peoples, first using unhewn stones and heaped or packed earth before transitioning toward masonry.[27] In the Highlands, the transition to masonry was preceded by the construction of tombs from massive stone slabs collectively hauled by community members to the tomb site. Late 18th century Merina king Andrianampoinimerina is said to have encouraged the construction of such tombs, observing "A house is for a lifetime but a tomb is for eternity."[27]

Highlands traditions

In the Highlands of Imerina, the above-ground entrances of ancient tombs were originally marked by standing stones and the walls were formed of loosely stacked flat stones.[27] Examples of these ancient tombs can be found at some of the twelve sacred hills of Imerina. Where a body was not able to be retrieved for burial (as in times of war), a tall, unmarked standing stone (vatolahy, or "male stone") was sometimes traditionally erected in memory of the deceased.[17] Andrianampoinimerina promoted more elaborate and costly tomb construction as a worthy expense for honoring one's ancestors. He also declared that the highest Merina andriana (noble) sub-castes would enjoy the privilege of constructing a small house on top of a tomb to distinguish them from the tombs of lower castes.[13] The two highest andriana sub-castes, the Zanakandriana and the Zazamarolahy, built tomb houses called trano masina ("sacred house"), while the tomb houses of the Andriamasinavalona were called trano manara ("cold house"). These houses were identical to standard wooden nobles' houses except for the fact that they had no windows and no hearth.[28] While the lamba-wrapped remains were laid to rest on stone slabs in the tomb below, the deceased's valuable possessions such as gold and silver coins, elegant silk lambas, decorative objects and more were placed in the trano masina or trano manara, which was often decorated much like a regular room with comfortable furniture and refreshments such as rum and water for the deceased's spirit to enjoy. The trano masina of King Radama I, which burned with other structures in the 1995 fire at the Rova palace compound in Antananarivo, was said to be the richest known.[13]

Today, tombs may be constructed using traditional methods and materials or incorporate modern innovations such as concrete.[29] Inside, superimposed slabs of stone or concrete line the walls. The bodies of the ancestors of an individual family are wrapped in silk shrouds and laid to sleep on these slabs.[17] Among the Merina, Betsileo and Tsihanaka, the remains are periodically removed for the famadihana, a celebration in honor of the ancestors, wherein the remains are re-wrapped in fresh shrouds amid extravagant communal festivities before being once again laid to rest in the tomb. The significant expense associated with tomb construction, funerals and reburial ceremonies honors the ancestors even as it counters the emergence of unequal wealth distribution in traditional communities.[25]

Southern and western traditions

The tombs found in the southwest of Madagascar are among the most striking and distinctive.[30] Like those in the Highlands they are generally rectangular and partially subterranean; modern tombs may incorporate concrete in addition to (or in place of) traditional stone. They are distinguished from Highlands tombs by their elaborate decoration: images may be painted on the exterior of the tomb, recalling events in an ancestor's life.[31] The roof of the tomb may be stacked with the horns of zebu sacrificed in the ancestor's honor at their funeral, and numerous aloalo—wooden funerary posts carved with symbolic patterns or images representing events in the life of the deceased—may be planted on top. The tombs of the Mahafaly people are especially famed for this type of construction.[30] Among the Sakalava of the western coast, aloalo may be topped with erotic carvings evocative of the cycle of birth, life and death.[17]

Modern architecture

Foreign architectural influences, having arisen through increased European contact over the course of the 19th century, intensified dramatically with the advent of French colonization in 1896.[4] Over the past several decades, the increasing availability of relatively inexpensive modern construction materials imported from China and elsewhere has further reinforced a growing trend in urban areas away from traditional architectural styles in favor of more durable but generic structures using industrially produced materials such as concrete and sheet metal.[23] Certain modern innovations may be more highly esteemed than others. In the Manambondro region, for instance, corrugated sheet metal roofing was typically the least expensive and prestigious and most common addition to a traditional house. The replacement of locally sourced wood frames with factory-milled lumber was the next most common house modification, followed by the laying of a concrete foundation. Houses built entirely of concrete with glass windows and imported decorative balcony railings and window bars implied great wealth and the highest social status. Although low income levels have served to preserve traditional construction among the majority of the population of Madagascar, due to the prestige associated with modern architectural innovations, traditional construction is often abandoned as income increases.[4]

A limited number of recently constructed homes in Antananarivo attempt to blend Malagasy architectural traditions with the comforts of modern house construction. These hybrids resemble traditional brick Highlands houses from the exterior, but use modern materials and construction techniques to efficiently incorporate electricity, plumbing, air conditioning and current kitchen features in a fully contemporary interior. This innovation is exemplified in the recent residential development at "Tana Water Front" in the Ambodivona district of downtown Antananarivo.[23]

Notes

- Wake, C. Staniland (1882). "Notes on the origins of the Malagasy". The Antananarivo Annual and Madagascar Magazine. 6: 21–33. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- Winzeler, Robert L. (2004). The architecture of life and death in Borneo. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2632-1.

- Kus, Susan; Raharijaona, Victor (2000). "House to Palace, Village to State: Scaling up Architecture and Ideology". American Anthropologist. New Series. 1 (102): 98–113. doi:10.1525/aa.2000.102.1.98.

- Thomas, Philip (September 1998). "Conspicuous Construction: Houses, Consumption and 'Relocalization' in Manambondro, Southeast Madagascar". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 4 (3): 425–446. doi:10.2307/3034155. JSTOR 3034155.

- Acquier, Jean-Louis (1997). Architectures de Madagascar (in French). Berlin: Berger-Levrault. ISBN 978-2-7003-1169-3.

- Kent, Susan (1993). Domestic architecture and the use of space: an interdisciplinary cross-cultural study. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-521-44577-1. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- Bloch, Maurice (1971). Placing the dead: tombs, ancestral villages and kinship organization in Madagascar. London: Berkeley Square House. ISBN 978-0-12-809150-0.

- Chapman, Olive (1940). "Primitive tribes in Madagascar". The Geographical Journal. 96 (1): 14–25. doi:10.2307/1788495. JSTOR 1788495.

- Kottak, Conrad (1986). Madagascar: Society and History. Carolina Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-89089-252-7.

- Gade, Daniel W. (1996). "Deforestation and its effects in Highland Madagascar". Mountain Research and Development. 16 (2): 101–116. doi:10.2307/3674005. JSTOR 3674005.

- Oliver, Samuel Pasfield (1886). Madagascar: an historical and descriptive account of the island and its former dependencies, Volume 2. Macmillan. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- Nativel, Didier (2005). Maisons royales, demures des grands à Madagascar (in French). Karthala Editions. ISBN 978-2-84586-539-6. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- Frémigacci, Jean (1999). "Le Rova de Tananarive: Destruction d'un lieu saint ou constitution d'une référence identitaire?". In Chrétien, Jean-Pierre (ed.). Histoire d'Afrique (in French). Editions Karthala. pp. 421–444. ISBN 978-2-86537-904-0. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- UNESCO. "Woodcrafting Knowledge of the Zafimaniry". Archived from the original on January 16, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- Bloch, Maurice (1995). "The Resurrection of the House Amongst the Zafimaniry of Madagascar". In Carsten, Janet; Hugh-Jones, Stephen (eds.). About the House: Lévi-Strauss and Beyond. Cambridge University Press. pp. 69–83. ISBN 978-0-521-47953-0. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- Linton, Ralph (1928). "Culture Areas in Madagascar". American Anthropologist. 30 (3): 363–390. doi:10.1525/aa.1928.30.3.02a00010.

- Sibree, James (1896). Madagascar before the conquest. T. Fisher Unwin. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- Ogot, Bethwell (1992). Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-101711-7. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- Tutwiler Wright, Henry (2007). Early state formation in central Madagascar: an archaeological survey of western Avaradrano. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-915703-63-0.

- Bradt, Hilary; Austin, Daniel (2007). Madagascar (9th ed.). Guilford, CT: Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-197-5. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- UNESCO. "Royal hill of Ambohimanga". Archived from the original on January 16, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- Cousins, William Edward (1895). Madagascar of to-day. The Religious Tract Society. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- Andriamihaja, Nasolo Valiavo (July 5, 2006). "Habitat traditionnel ancien par JP Testa (1970), Revue de Madagascar: Evolution syncrétique depuis Besakana jusqu'au trano gasy". L'Express de Madagascar (in French). Antananarivo. Archived from the original on January 16, 2011. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- Mouchet, Jean; Carnevale, Pierre; Manguin, Sylvie (2008). Biodiversity of malaria in the world. John Libbey Eurotext. p. 174. ISBN 978-2-7420-0616-8. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- Campbell, Gwyn (1993). "The Structure of Trade in Madagascar, 1750–1810". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 1 (26): 111–148. doi:10.2307/219188. JSTOR 219188.

- Vérin, Pierre (1986). The history of civilisation in North Madagascar. ISBN 978-90-6191-021-3.

- Bird, Randall (Winter 2005). "The Merina landscape in early 19th century highlands Madagascar". African Arts. 38 (4): 18–23, 91–92. doi:10.1162/afar.2005.38.4.18. JSTOR 20447730.

- Van Gennep, Arnold (1904). Tabou et totémisme à Madagascar: étude descriptive et théorique (in French). Ernest Leroux Editeur. pp. 126–127. ISBN 9785878397216. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- Vogel, Claude (1982). Les quatre-mères d'Ambohibaho: étude d'une population régionale d'Imerina (Madagascar) (in French). Selaf. ISBN 978-2-85297-074-8.

- Kaufmann, J.C. (2000). "Forget the Numbers: The Case of a Madagascar Famine". History in Africa. 27: 143–157. doi:10.2307/3172111. JSTOR 3172111.

- Australian Museum. "Burial – Madagascar". Archived from the original on January 16, 2011. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

External links

- Woodcrafting Knowledge of the Zafimaniry. UNESCO World Heritage YouTube channel.