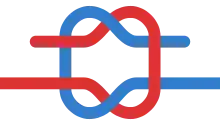

Reef knot

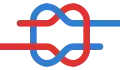

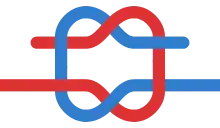

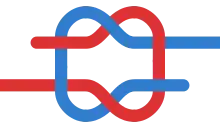

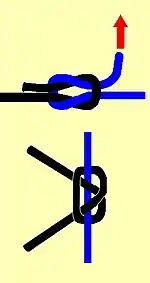

The reef knot, or square knot, is an ancient and simple binding knot used to secure a rope or line around an object. It is sometimes also referred to as a Hercules knot. The knot is formed by tying a left-handed overhand knot and then a right-handed overhand knot, or vice versa. A common mnemonic for this procedure is "right over left; left over right", which is often appended with the rhyming suffix "... makes a knot both tidy and tight". Two consecutive overhands of the same handedness will make a granny knot. The working ends of the reef knot must emerge both at the top or both at the bottom, otherwise a thief knot results.

The reef knot or square knot consists of two half knots, one left and one right, one being tied on top of the other, and either being tied first...The reef knot is unique in that it may be tied and tightened with both ends. It is universally used for parcels, rolls and bundles. At sea it is always employed in reefing and furling sails and stopping clothes for drying. But under no circumstances should it ever be tied as a bend, for if tied with two ends of unequal size, or if one end is stiffer or smoother than the other, the knot is almost bound to spill. Except for its true purpose of binding it is a knot to be shunned.

| Reef knot | |

|---|---|

| |

| Names | Reef knot, Square knot, Hercules knot, Double knot, brother hood knot |

| Category | Binding |

| Origin | Ancient |

| Related | Thief knot, Granny knot, Grief knot, Surgeon's knot, Shoelace knot |

| Releasing | Jamming |

| Typical use | Joining two ends of a single line to bind around an object. |

| Caveat | Not secure as a bend. Spills easily if one of the free ends is pulled outward. Does not hold well if the two lines are not the same thickness. |

| ABoK | #74, #75, #460, #1204, #1402, #2096, #2573, #2574, #2577, #2580 |

| Instructions | |

The reef knot is not recommended for tying two ropes together, because of the potential instability of the knot; something that has resulted in many deaths (see Misuse as a bend).

Naming

The reef knot is at least 4,000 years old. The name "reef knot" dates from at least 1794[2] and originates from its common use to reef sails,[3][4] that is to tie part of the sail down to decrease its effective surface area in strong winds. To release the knot a sailor could collapse it with a pull of one hand; the sail's weight would make the collapsed knot come apart. It is specifically this behavior which makes the knot unsafe for connecting two ropes together.[5]

The name "square knot" is found in Dana's 1841 maritime compendium A Seaman's Friend, which also gives "reef knot" as an alternative name.[6][7]

The name square knot is often used for the unslipped version of reef knot. Reef knot itself then is understood as the single slipped version, while the name shoelace knot is to indicate double slipped version. Sometimes the name bowtie also may be used to indicate a double slipped version, but tying a bowtie is usually performed on flat material, and involves a slip knot of one end holding a bight of the other end i.e. not really a double slipped reef knot. The name "Square knot" is also used for completely different other knots such as the mathematical concept of square knot, or friendship knot; this last one earns the name by being flat and drawing a square on one face (and a cross on the other face).

Uses

The reef knot is used to tie the two ends of a single rope pieces together such that they will secure something, for example a bundle of objects, that is unlikely to move much. In addition to being used by sailors for reefing and furling sails, it is also one of the key knots of macrame textiles.[8]

The knot lies flat when made with cloth and has been used for tying bandages for millennia. As a binding knot it was known to the ancient Greeks as the Hercules knot (Herakleotikon hamma) and is still used extensively in medicine.[9] In his Natural History, Pliny relates the belief that wounds heal more quickly when bound with a Hercules knot.[10]

It has also been used since ancient times to tie belts and sashes. A modern use in this manner includes tying the obi (or belt) of a martial arts keikogi.

With both ends tucked (slipped) it becomes a good way to tie shoelaces, whilst the non-slipped version is useful for shoelaces that are excessively short. It is appropriate for tying plastic garbage or trash bags, as the knot forms a handle when tied in two twisted edges of the bag.

The reef knot figures prominently in Scouting worldwide. It is included in the international membership badge[11] and many scouting awards.[12] In the Boy Scouts of America demonstrating the proper tying of the square knot is a requirement for all boys joining the program.[13] In Pioneering (Scouting), it is commonly used as a binding knot to finish off specialized lashing (ropework) and whipping knots.[14] However, it is an insecure knot, unstable when jiggled, and is not suitable for supporting weight.

A surgeon's variation, used where a third hand is unavailable, is made with two or three twists of the ropes on bottom, and sometimes on top, instead of just one.

Detail of Egyptian statue dating from 2350 BC depicting a reef knot securing a belt

Detail of Egyptian statue dating from 2350 BC depicting a reef knot securing a belt_300_bC.jpg.webp) Ancient Greek jewelry from Pontika (now in Russia), 300 BC, in the form of a reef knot

Ancient Greek jewelry from Pontika (now in Russia), 300 BC, in the form of a reef knot Singly slipped reef knot

Singly slipped reef knot Diagram of common shoelace bow knot, a doubly slipped reef knot

Diagram of common shoelace bow knot, a doubly slipped reef knot Weight for weighing gold dust - Knot – MHNT

Weight for weighing gold dust - Knot – MHNT

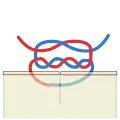

Misuse as a bend

The reef knot's familiarity, ease of tying, and visually appealing symmetry conceal its weakness. The International Guild of Knot Tyers warns that this knot should never be used to bend two ropes together.[15] A proper bend knot, for instance a sheet bend or double fisherman's knot, should be used instead. Knotting authority Clifford Ashley claimed that misused reef knots have caused more deaths and injuries than all other knots combined.[16] Further, it is easily confused with the granny knot, which is a very poor knot.

Physical analysis

An approximate physical analysis[17] predicts that a reef knot will hold if , where μ is the relevant coefficient of friction. This inequality holds if . Experiments show that the critical value of μ is actually somewhat lower.[18]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Square knots. |

Notes and references

- Ashley, Clifford W. (1944). The Ashley Book of Knots, p.220. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-04025-3.

- David Steel (1794), The Elements and Practice of Rigging and Seamanship, London: David Steel, p. 183

- Lever, Darcy (1998) [1819], The Young Sea Officer's Sheet Anchor (2nd ed.), Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, p. 83, ISBN 978-0-486-40220-8

- Cyrus Lawrence Day (1986), The Art of Knotting and Splicing (4th ed.), Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, p. 42

- Ashley, Clifford W. (1944), The Ashley Book of Knots, New York: Doubleday, p. 258, ISBN 978-0-385-04025-9

- Ashley, p. 220.

- Richard Henry Dana Jr. (1997) [1879], The Seaman's Friend: A Treatise on Practical Seamanship (14th revised and corrected ed.), Mineola, NY: Dover, p. 49, ISBN 0-486-29918-X

- Ashley, pp. 399-400.

- Hage, J. Joris (April 2008), "Heraklas on Knots: Sixteen Surgical Nooses and Knots from the First Century A.D.", World Journal of Surgery, 32 (4), pp. 648–655, doi:10.1007/s00268-007-9359-x, PMID 18224483, S2CID 21340612

- Pliny the Elder, Bostock, John; Riley, H. T. (eds.), The Natural History, p. 28.17, retrieved 2009-08-23

- See File:World Scout Emblem 1955.svg for an image of the emblem.

- Square Knots - Meaning and Placement, retrieved 2009-08-17

- Boy Scouts of America, Boy Scout Joining Requirements, retrieved 2009-08-23

- "Foolproof Way to ALWAYS Tie a Square Knot Right". www.scoutpioneering.com. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- International Guild of Knot Tyers, Sea Cadet Knots, retrieved 2016-04-19

- Ashley, p. 18.

- Maddocks, J.H. and Keller, J. B., "Ropes in Equilibrium," SIAM J Appl. Math., 47 (1987), pp. 1185-1200

- Crowell, "The physics of knots," http://www.lightandmatter.com/article/knots.html

External links

| Look up square knot in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |