Obi (sash)

An obi (帯) is a belt of varying size and shape worn with both traditional Japanese clothing and uniforms for Japanese martial arts styles. Originating as a simple thin belt in Heian period Japan, the obi developed over time into a belt with a number of different varieties, with a number of different sizes and proportions, lengths, and methods of tying. The obi, which once did not differ significantly in appearance between men and women, also developed into a greater variety of styles for women than for men.

Despite the kimono having been at one point and continuing to appear to be held shut by the obi, many modern obi are too wide and stiff to function in this way, with a series of ties known as koshihimo, worn underneath the obi, used to keep the kimono closed instead.

Obi are categorised by their design, formality, material, and use, and can be made of a number of types of fabric, with heavy brocade weaves worn for formal occasions, and some lightweight silk obi worn for informal occasions. Obi are also made from materials other than silk, such as cotton, hemp and polyester, though silk obi are considered a necessity for formal occasions. In the modern day, pre-tied obi, known as tsuke or tsukiri obi, are also worn, and do not appear any different to a regular obi when worn.

Though obi can be inexpensive when bought second-hand, they typically cost more than a kimono, particularly when purchased brand-new. A number of specialist fabrics used particularly to make obi are highly prized for their craftsmanship and reputation of quality, such as nishijin-ori, produced in the Nishijin district of Kyoto, and hakata-ori produced in Fukuoka prefecture.

History

Heian period to Edo period

In its early days, the obi was a cord or ribbon-like sash, approximately 8 centimetres (3.1 in) in width. Men's and women's obi were similar. At the beginning of the 17th century, both women and men wore a thin, ribbon-like obi. By the 1680s, the width of women's obi had already doubled from its original size. In the 1730s women's obi were about 25 centimetres (9.8 in) wide, and at the turn of the 19th century were as wide as 30 centimetres (12 in). At that time, separate ties and cords were necessary to hold the obi in place. Men's obi were widest in the 1730s, at about 16 centimetres (6.3 in).[1]

Before the Edo period, which began in the mid-1600s, kosode robes were fastened with a narrow sash at the hips.[2] The mode of attaching the sleeve widely to the torso part of the garment would have prevented the use of wider obi. When the sleeves of the kosode began to grow in width (i.e. in length) at the beginning of the Edo period, the obi widened as well. There were two reasons for this: firstly, to maintain the aesthetic balance of the outfit, the longer sleeves needed a wider sash to accompany them; secondly, unlike today (where they are customary only for unmarried women) married women also wore long-sleeved kimono in the 1770s. The use of long sleeves without leaving the underarm open would have hindered movements greatly. These underarm openings in turn made room for even wider obi.[1]

Originally, all obi were tied in the front. Later, fashion began to affect the position of the knot, and obi could be tied to the side or to the back. As obi grew wider the knots grew bigger, and it became cumbersome to tie the obi in the front. In the end of the 17th century obi were mostly tied in the back. However, the custom did not become firmly established before the beginning of the 20th century.[1]

At the end of the 18th century it was fashionable for a woman's kosode to have overly long hems that were allowed to trail behind when in house. For moving outside, the excess cloth was tied up beneath the obi with a wide cloth ribbon called shigoki obi. Contemporary women's kimono are made similarly over-long, but the hems are not allowed to trail; the excess cloth is tied up to hips, forming a fold called the ohashori. Shigoki obi are still used, but only as a decorative accessory.[1]

Modern day

The most formal women's obi, the maru obi, is technically obsolete, worn only by some brides, and a modified version worn by maiko, in the present day. The lighter fukuro obi has taken the place of maru obi. The originally everyday nagoya obi is the most common obi used today, and the fancier ones may even be accepted as a part of a semi-ceremonial outfit. The use of fancy, decorative obi knots has also narrowed, though mainly through the drop in the numbers of women wearing kimono on a regular basis, with most women tying their obi in the taiko musubi (lit., "drum knot") style.[3] Tsuke obi, also known as tsukiri obi, have gained popularity as pre-tied belts accessible to those with mobility issues or a lack of knowledge on how to wear obi.

Tatsumura Textile located in Nishijin in Kyoto is a centre of manufacturing today. Founded by Heizo Tatsumura I in the 19th century, it is renowned for making some of the most luxurious obi.[4] Amongst his students studying design was the later-painter Inshō Dōmoto. The technique nishijin-ori is intricately woven and can have a three dimensional effect, costing up to 1 million Yen.[5][6][7]

The "Kimono Institute" was founded by Kazuko Hattori in the 20th century and teaches how to tie an obi and wear it properly.[8][9][10][11]

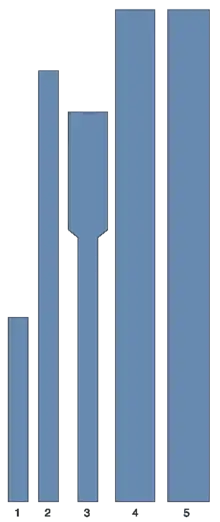

Women's obi

1. Tsuke/tsukuri/kantan obi

2. Hanhaba obi

3. Nagoya obi

4. Fukuro obi

5. Maru obi

There are many types of obi for women, with certain types of obi worn only with certain types of kimono to certain occasions.[12][13] Often, the obi can adjust the formality of the entire kimono outfit, with the same kimono being worn to occasions of differing formality depending on the obi worn with it.[14] Most women's obi no longer keep the kimono closed, owing to their stiffness and width, and a number of ties worn under the obi keep the kimono in place.

A woman's formal obi can be 30 centimetres (12 in) wide and more than 4 metres (13 ft) long, with the longest variety – the darari obi, nearing 6 metres (20 ft) in length – worn only by maiko in some regions of Japan. Some women's obi are folded in two width-wise when worn, to a width of about 15 centimetres (5.9 in) to 20 centimetres (7.9 in); the full width of the obi is present only in the knot at the back of the kimono, with the band around the middle appearing to be half-width when worn.

There are a number of different ways to tie an obi, and different knots are suited to different occasions and different kimono. The obi itself often requires the use of stiffeners and cords for definition of shape and decoration, and some knots, such as the taiko musubi, require additional accessories in order to keep their shape.

Women's obi types

- Darari obi (だらり帯, "dangling obi") are very long maru obi worn by maiko in some regions of Japan. A maiko's darari obi features the crest of the geisha house she is affiliated with at the end of the obi, below the kaikiri (end lines). Darari obi can be 600 centimetres (20 ft) long.

- Fukuro obi (袋帯, "pouch obi") are slightly less formal than maru obi, despite being functionally the most formal variety of obi worn today.[15][3] Fukuro obi are made from either a single double-width length of fabric with a seam down one edge, or from two lengths of fabric sewn together down each edge; for fukuro obi made from two lengths of fabric, the fabric used for the backside may be cheaper and appear to be more plain.[16]Fukuro obi are made in roughly three subtypes. The most formal and expensive of these is patterned brocade on both sides. The second type is two-thirds patterned, the so-called "60% fukuro obi", and is somewhat cheaper and lighter than the first type. The third type has patterns only in the parts that will be prominent when the obi is worn in the common taiko musubi style.[3][15] Fukuro obi are roughly 30 centimetres (12 in) wide and 360 centimetres (11.8 ft) to 450 centimetres (14.8 ft) long.

When worn, a fukuro obi is nearly impossible to tell from a maru obi.[15] - Fukuro nagoya obi (袋名古屋帯) or hassun nagoya obi (八寸名古屋帯, "eight-inch nagoya obi") is an obi that has been sewn in two only where the taiko knot would begin. The part wound around the body is folded when put on. The fukuro nagoya obi is intended for making the more formal, two-layer variation of the taiko musubi, known as the nijuudaiko musubi. It is about 350 centimetres (11.5 ft) long.[16]

- Hoso obi (細帯, "thin sash") is a collective name for informal half-width obi. Hoso obi are 15 centimetres (5.9 in) to 20 centimetres (7.9 in) wide and roughly 330 centimetres (10.8 ft) long.[16]

- Hanhaba obi (半幅帯[17] / 半巾帯, "half-width obi") are a type of thin and informal obi[16] worn with a yukata or a lower-formality komon.[15] Hanhaba obi are very popular, as they are easy to wear, relatively cheap, and often come in a variety of colourful designs.[18] For use with yukata, reversible hanhaba obi are popular: they can be folded and twisted in several ways to create colour effects.[19] A hanhaba obi is 15 centimetres (5.9 in) wide and 300 centimetres (9.8 ft) to 400 centimetres (13 ft) long. Tying it is relatively easy,[18] and does not require pads or strings.[14] The knots used for hanhaba obi are often simplified versions of bunko-musubi. As it is easy to tie and less formal, the hanhaba obi is sometimes worn in self-invented styles, often with decorative ribbons and accessories.[18][19]

- Kobukuro obi (小袋帯) is an unlined hoso obi roughly 15 centimetres (5.9 in) to 20 centimetres (7.9 in) wide and roughly 300 centimetres (9.8 ft) long.[16]

- Hara-awase obi (典雅帯) or chūya obi (昼夜帯, "day-and-night obi") is an informal obi[13] that has sides of different colours. Having been historically popular, the chūya obi is frequently seen in woodblock prints and photographs from the Edo and Meiji periods, and most chūya obi are vintage or antique pieces; it is not as frequently made or worn today.[3] Chūya obi typically have a dark, sparingly decorated underside and a more colourful, decorated topside; the underside is commonly plain black satin silk (shusu silk) with no decoration, though chūya obi with decoration on both sides do exist. Chūya obi are frequently not lined, making them relatively floppy, soft and easy to tie. They are about 30 centimetres (12 in) wide and 350 centimetres (11.5 ft) to 400 centimetres (13 ft) long.

- Heko obi (兵児帯, "soft obi") is a very informal obi made of soft, thin cloth,[14] often dyed with shibori.[16] Its traditional use is as an informal obi for children and men,[16][20] and though historically would have been inappropriate for women to wear, the heko obi is now also worn by young girls and women with modern, informal kimono and yukata. An adult's heko obi is roughly the same size of any other adult obi, about 20 centimetres (7.9 in) to 30 centimetres (12 in) wide and about 300 centimetres (9.8 ft) long.[20]

- Hitoe obi (単帯, "one-layer obi"[21]) are made from cloth stiff enough that the obi does not need a lining or a sewn-in stiffener. One well-known type of hitoe obi is the hakata-ori (博多織) obi, which consists of thick weft thread interwoven with thin warp thread with a stiff, tight weave;[22] obi made from this material are also called hakata obi (博多帯). A hitoe obi can be worn with everyday kimono or yukata.[13][21] A hitoe obi is 15 centimetres (5.9 in) to 20 centimetres (7.9 in) wide (the so-called hanhaba obi)[16] or 30 centimetres (12 in) wide and about 400 centimetres (13 ft)[16] long.

- Kyōbukuro obi (京袋帯, "capital fukuro obi") was invented in the 1970s in Nishijin, Kyoto.[16] It lies between the nagoya obi and the fukuro obi in terms of formality and use, and can be used to smarten up an everyday outfit.[16] A kyōbukuro obi is structured like a fukuro obi but is as short as a nagoya obi.[16] It thus can also be turned inside out for wear like reversible obi.[16] A kyōbukuro obi is about 30 centimetres (12 in) wide and 350 centimetres (11.5 ft) long.[16]

- Maru obi (丸帯, "one-piece obi") is the most formal type of women's obi, though all but obsolete today. It is made from cloth about 68 cm wide[20] and is folded around a double lining and sewn together. Maru obi were at their most popular during the Taishō and Meiji periods.[15] Their bulk and weight make maru obi difficult to tie by oneself, and are worn only by maiko and brides in the present day.[15] A maru obi is about 30 centimetres (12 in) to 35 centimetres (14 in) wide and 360 centimetres (11.8 ft) to 450 centimetres (14.8 ft) long,[16][18] fully patterned[20] and is often embroidered with metal-coated yarn and foilwork.[14]

- Manaita obi (俎板帯, "chopping board obi") is the style of front-tied, flat obi worn historically by some oiran (courtesans), and now worn by courtesan-reenactors and kabuki actors on stage. Manaita obi are thickly padded and commonly feature large-scale, heavily-decorated and sometimes three-dimensional motifs such as butterflies, clouds and Chinese dragons, typically on a background of satin silk.

- Nagoya obi (名古屋帯) – also called kyūsun nagoya obi (九寸名古屋帯, "nine-inch nagoya obi")[16] – is the most-used obi type today. A nagoya obi is distinguished by its structure: one end is folded and sewn in half, the other end is of full width.[15] This is to make putting the obi on easier. A nagoya obi can be partly- or fully-patterned. It is normally worn only in the taiko musubi style, and many nagoya obi are designed so that they have patterns only in the part that will be most prominent in the knot. Nagoya obi are shorter than other obi types, about 315 centimetres (10.33 ft) to 345 centimetres (11.32 ft) long, but of the same width, about 30 centimetres (12 in).[18]

The nagoya obi is relatively new, developed by a seamstress living in Nagoya at the end of the 1920s. The new, easy-to-use obi gained popularity among Tokyo's geisha, from whom it then was adopted by fashionable city women for their everyday wear.[3]

The formality of a nagoya obi depends on its material, just as with other obi types. Since the nagoya obi was originally used as everyday wear, it cannot be worn to very formal occasions, but a nagoya obi made from heavy brocade is considered acceptable as semi-ceremonial wear.[3]

The term "nagoya obi" can also refer to another obi with the same name, used centuries ago. This nagoya obi was cord-like.[13] - Odori obi (踊帯, "dance obi") is a name for obi used in dance acts.[13] An odori obi is typically simply-patterned with large, obvious motifs, commonly woven in gold or silver metallic threads, so as to be easily-visible from the audience. Odori obi can be 10 centimetres (3.9 in) to 30 centimetres (12 in) wide and 350 centimetres (11.5 ft) to 450 centimetres (14.8 ft) long. As the term "odori obi" is not established, it can refer to any obi meant for dance acts, though is generally understood to refer to obi with large and simplistic metallic designs.[13]

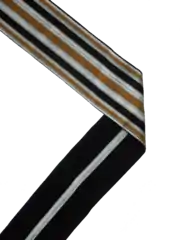

- Sakiori obi (裂織帯, "rag weave obi") are a style of obi made by using strips of old cloth, woven into a narrow, striped fabric. The warp yarn is typically an actual yarn, whereas the strips of recycled cloth as used as the weft; though narrow, sakiori obi may require cloth the equivalent of three kimonos' worth to create. Historically woven at home out of necessity, sakiori obi are informal, and are generally not worn outside the house. A sakiori obi is similar to a hanhaba obi in size, and though informal, is prized as an example of rural craftsmanship.

- Tenga obi (典雅帯, "fancy obi") resemble hanhaba obi, but are considered to be more formal. They are usually wider and made from fancier cloth more suitable for celebration. The patterns usually include auspicious, celebratory motifs. A tenga obi is about 20 centimetres (7.9 in) wide and 350 centimetres (11.5 ft) to 400 centimetres (13 ft) long.

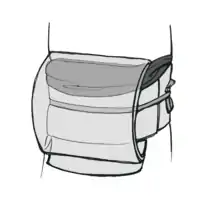

- Tsuke obi (付け帯) or tsukuri obi (作り帯) or kantan obi (簡単帯, "easy obi") refers to any ready-tied obi, regardless of the knot the obi has been sewn into. It often has a separate, internally-stiffened knot piece, and a piece that is wrapped around the waist. The tsuke obi is fastened in place by ribbons attached to each piece.[23] Tsuke obi are most commonly informal styles of obi, though more formal pre-tied obi do exist, as they are indistinguishable from a regular obi when worn.[21]

Accessories for women's obi

- Obiage (帯揚げ, "obi bustle"[24]) is a scarf-like length of cloth worn above the obi. Though it functions as decoration, it may also function to cover the obimakura[25] and keep the upper part of the obi knot in place.[13][21] The obiage can be worn by women at any age, with it being custom to show more of the obiage the younger one is. It can be tied in a variety of different ways, and is commonly dyed using the shibori – typically the kanoko shibori – dye technique.

- Obidome (帯留, "sash clip"[24]) is a small, decorative brooch fastened onto the obijime at the front, commonly made from precious metals and gemstones. Though most obidome are relatively small, the obidome worn by maiko are comparably much larger, and may be the most expensive item of the maiko's finished outfit. Certain types of obijime are woven specifically for obidome to be fastened to them.[25]

- Obi-ita are long stiffeners inserted between folds of the obi at the front, giving it a smooth, flat appearance.[13][25] Some types of obi-ita are attached around the waist with cords before the obi is put on; obi-ita are available in a number of different sizes, weights and materials to suit both the season and the obi itself.[25]

- Obijime (帯締め) are decorative cords roughly 150 centimetres (4.9 ft) long[25] tied around the obi and knotted at either the front or the back. The obijime can be both functional and decorative, serving to keep certain obi musubi in place and add extra decoration to an outfit.[20] Most obijime are woven silk, with a number of varieties - such as rounded obijime worn with furisode, open-weave obijime worn for summer and obijime with gold and silver threads worn to formal occasions - available. One less commonly-worn variety of obijime, the maruguke obijime, is not a woven cord, and is instead a sewn, stuffed tube of fabric; this variety is generally only worn with furisode worn to highly formal events and on stage by kabuki actors. Woven or otherwise, most obijime feature tassels at each end.[20]

- Obimakura (帯枕, "obi pillow") is a small pillow that supports and shapes the obi knot.[13] The most common knot worn by women today, the taiko musubi, is shaped and held in place with the use of an obimakura; elsewhere, one or two large obimakura are used in the tying of the darari musubi worn by some maiko.[25]

Men's obi

about 6 centimetres (2.4 in) wide

The obi worn by men are much narrower than those of women, with the width of most men's obi being about 10 centimetres (3.9 in) at the most. Men's obi are worn in a much simpler fashion than women's, worn below the stomach and tied in a number of relatively simple knots at the back - requiring no obijime, obiage, obi-ita or obimakura to achieve.

Men's obi types

- Heko obi (兵児帯, lit., "waistband") are soft, informal obi[16] made from drapey and often shibori-dyed fabrics such as crêpe, silk habutai, cotton and others. It is generally tied in a loose, casual knot; though heko obi for children are short, heko obi for adults are roughly as long as any other adult-sized obi – 350 centimetres (11.5 ft) to 400 centimetres (13 ft) long – but can be comparably wider, at up to 74 centimetres (29 in).[26] Adult men generally wear heko obi only at home or in the summer months with a yukata,[16] whereas young boys can wear it in public at mostly any time of year.

- Kaku obi (角帯, "stiff obi") is the second type of men's obi, roughly 10 centimetres (3.9 in) wide and 400 centimetres (13 ft) long.[16] Depending on its material, colours and patterns, kaku obi are suitable for any and all occasions, from the most informal to the most formal of situations. Kaku obi are most commonly made of hakata-ori[16]), but can also be made from silk pongee (known as tsumugi), silk gauze and heavier, brocade-type weaves of silk.[27] A variety of obi knots exist for the kaku obi, and it is most commonly worn in the kai-no-kuchi knot.

Accessories

Men's obi are not generally worn with accessories, being for the most part too thin to accommodate any of the accessories worn with women's obi.

However, in the Edo period, practical box-shaped accessories called inro (印籠), which hung from kaku obi with a fastener called netsuke, became popular. Sagemono is a general term for bags and boxes for cigarettes, pipes, ink, brushes, etc. Among them, a small stackable box for seals and medicines is inro. Inro, which originated in the Sengoku period, were first used as practical goods, but after the middle of the Edo period, when inro were gorgeously decorated with various lacquer techniques such as maki-e and raden, samurai and wealthy merchants competed to collect them and wore them as accessories with kimono. And from the end of the Edo period to the Meiji period, inro became a complete art collection. Nowadays, inro are rarely worn as kimono accessories, but there are collectors all over the world.[28][29]

Children's obi

Children's obi are generally soft, simple sashes, designed to be easy and comfortable to wear, though older children may wear simple, stiffer obi made short, such as hanhaba obi and kaku obi; as they age, children begin to wear kimono outfits that are essentially miniaturised versions of adult kimono and obi.[30] The youngest children wear soft, scarf-like obi.

Children's obi types

- Sanjaku obi (三尺帯, さんじゃくおび, "three-foot-long obi") is a type of men's obi. It is named for its length, three old Japanese feet (鯨尺, about 37.9 centimetres (14.9 in)). The obi is sometimes known simply as 三尺 (sanjaku). During the Edo period, it gained popularity as a simple and easy-to-wear obi paired with casual, everyday kimono. According to some theories, the sanjaku obi originates from a scarf of the same length, which was folded and used as a sash. A sanjaku obi typically is shaped like a kaku obi, narrow and with short stitches. It is usually made from soft cotton-like cloth. Because of its shortness, the sanjaku obi is tied in the koma musubi style, which is much like a square knot.

- Shigoki-obi (しごき帯) were previously worn to prevent kimono from trailing along the floor when walking outside, used to tie up the excess length when going out; over time, this style of wear became the standard for wearing kimono both inside and outside, evolving into the ohashori hip fold worn today. Nowadays the shigoki obi's only function is decorative.[1] It is part of a 7-year-old girl's outfit for celebration of Shichi-Go-San.[31]

- Tsuke obi (pre-tied obi) are popular as children's obi because of their ease of use. There are even formal tsuke obi available for children.[31] These obi correspond to fukuro obi on the formality scale.[31]

In martial arts

Many Japanese martial arts feature an obi as part of their uniform. These obi are often made of thick cotton and are about 5 centimetres (2.0 in) wide. The martial arts obi are most often worn in the koma musubi style; in practice where the hakama is worn, the obi is tied in other ways.

In many martial arts the colour of the obi signifies the wearer's skill level. Usually the colours start from the beginner's white and end in the advanced black, or masters' red and white. When the exercise outfit includes a hakama, the colour of the obi has no significance.

Knots (musubi)

The knot tied with the obi is known as the musubi (結び/むすび, lit., "knot"). Though obi functioned to hold the kimono closed for many centuries, beginning in the Edo period, the obi became too wide and/or too stiff to function effectively in this manner. In the modern day, a number of ties and accessories are used to keep the kimono in place, with the obi functioning in a more decorative capacity.

Though most styles of obi musubi can be tied by oneself, some varieties of formal women's obi can be difficult to tie successfully without the assistance of others.

There are hundreds of decorative knots,[13][21] particularly for women, often named for their resemblance to flowers, animals and birds. Obi knots follow the same rough conventions of style and suitability as kimono do, with the more complex and fanciful knots reserved for younger women on festive occasions, and knots with a plainer appearance being mostly worn by older women; however, some knots, such as the taiko musubi, have become the standard knot for women of all ages, excluding young girls.

In earlier days, the knots were believed to banish malicious spirits.[13] Many knots have a name with an auspicious double meaning.[13]

Types of knots

- Asagao musubi (朝顔結び/あさがおむすび, "morning glory knot") is a knot resembling the Japanese morning glory, suitable to be worn with yukata. The knot requires a very long obi, so it can be usually only be made for little girls.[19]

- Ayame musubi (菖蒲結び/あやめむすび, "iris knot") is a very complex and decorative knot resembling an iris blossom. It is considered suitable for young women in informal situations and parties. Because of the complexity and conspicuousness of the knot, it should be worn with more subdued, preferably monochrome kimono and obi.[32]

- Bara musubi (薔薇結び/バラむすび, "rose knot") is a contemporary knot suitable for young women, often worn to formal occasions at the lowest end of "formal". Because of the complexity of the knot, a multi-coloured or strongly patterned obi should not be used, and the patterns of the kimono should generally match the knot.[33]

- Chōchō musubi (蝶蝶結び/ちょうちょうむすび, "butterfly knot") is a version of the bunko musubi, tied using the hanhaba obi. Most pre-tied hanhaba obi are tied with this knot.

- Darari musubi (だらりむすび, "dangling knot") is a knot worn only by maiko, dancers and kabuki actors. It is easily distinguishable by its long "tails" hanging in the back, which require an obi of up to 6 metres (20 ft) in length to achieve. In the past, courtesans[13] and daughters of rich merchants would also have their obi tied in this manner. A half-length version of this knot, known as the handara musubi (lit., "half-dangling knot"), also exists, with apprentice geisha in some regions of Japan wearing this at various stages throughout their apprenticeship. The darari musubi is worn specifically by maiko in Gion to perform the gion kouta, a well-known short song performed at geisha parties whose lyrics - "dear lovely Gion, the dangling obi" - explicitly mention it, referring to the classical image of Gion's maiko.

- Fukura-suzume musubi (ふくら雀結び, "puffed sparrow knot") is a decorative knot that resembles a sparrow with its wings spread, and is generally worn only by young women. It is suitable for formal occasions and is typically only worn with a furisode. Traditionally, the fukura-suzume musubi worn with a furisode indicated a woman was available for marriage.

- Kai-no-kuchi musubi (貝の口むすび, "clam's mouth knot") is a subdued obi which is commonly worn by men, and sometimes worn by older women for convenience, or by women in general as a style choice.

- Koma musubi (駒結び, "foal knot") is a square knot often used for tying haori and obijime. The short sanjaku obi worn by children is also tied in this way.

- Taiko musubi (太鼓結び, "drum knot") is the most commonly-worn knot worn by women in the present day. It is a knot with a simple, subdued appearance, and resembles a box with a short tail underneath. The taiko musubi is suitable for women of almost every age, mostly every kind of kimono, and is suitable for mostly all occasions; only furisode and mostly all yukata are considered unsuitable to be worn with the taiko musubi. Though the knot is associated with the taiko drum, the knot was actually created to celebrate the opening of the Taikobashi bridge in Tokyo in 1823 by some geisha, a style which soon widely caught on.[13][34]

- Nijūdaiko musubi (二重太鼓結び, "two-layer drum knot") is a version of the taiko musubi, tied with the formal fukuro obi. Fukuro obi are longer than the nagoya obi, so the obi must be folded in two when tying the knot.[14] The knot has an auspicious double meaning of "double joy".[35]

- Tateya musubi (立て矢むすび, "standing arrow knot"[36]) is a knot resembling a large bow, and is one of the most simple knots worn with the furisode. According to kitsuke (kimono dressing) teacher Norio Yamanaka, it is the most suitable knot to be used with the honburisode - a furisode with full length sleeves.[36]

- Washikusa musubi (鷲草結び, "eagle plant knot") is a bow resembling a certain plant thought to look like an eagle taking flight.[37]

See also

- Kimono

- Obi strip: a paper band around a book

- Traditional Japanese clothing

Gallery

A complex obi knot worn as part of a wedding ourfit

A complex obi knot worn as part of a wedding ourfit Tying a hanhaba obi around a yukata

Tying a hanhaba obi around a yukata A maiko in Kyoto wearing an obi tied in the darari style

A maiko in Kyoto wearing an obi tied in the darari style The washikusa musubi

The washikusa musubi

Notes

- Dalby, pp. 47–55

- Fält et al., p. 450.

- Dalby, pp. 208–212

- "About Heizo 1st Tatsumura – Official Site of Tatsumura Textile, Kyoto". www.tatsumuraarttextiles.com.

- "Nishijin-ori Fabric – Authentic Japanese product". japan-brand.jnto.go.jp.

- "JAL Guide to Japan – Nishijin-ori Weaving and Textiles". www.world.jal.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-10-07. Retrieved 2007-10-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "着物の着付けを学ぶなら|服部和子きもの学院(本校・京都)". kimonomuseum.com.

- http://www.minpaku.ac.jp/sites/default/files/research/activity/news/rm/pdf/100827_hattori.pdf

- "『"服部和子ワールド" モテマナー講座開催☆』". ameblo.jp.

- http://www.thekyoto.net/kyoukyou/0811/081113_03/%5B%5D

- Fält et al., p. 452.

- Yoshino Antiques. "Kimono". Archived from the original on 2009-03-26. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- "Types of Obi". Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- "Japanese Obi Types". Archived from the original on 2012-10-22. Retrieved 2009-03-06.

- Toma-san. 帯の種類について (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2008-12-20. Retrieved 2009-03-08.

- 出張着付・半巾帯の販売・着付講習 "京都 宇ゐ" (in Japanese). Retrieved 2009-03-06.

- "More about obi". Kimono Flea Market Ichiroya. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- Toma-san. "Archived copy" 浴衣の帯結びの色々 (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2008-10-17. Retrieved 2009-03-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Glossary". Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- Kimono Place. "Glossary". Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- "What's HAKATA-ORI?". 21st Century HAKATA-ORI Japan Brand. Archived from the original on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2011-07-17.

- Toma-san. "Archived copy" 作り帯のつけ方 (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2009-02-08. Retrieved 2009-03-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- David, Vee (2013). The Kanji Handbook. Tuttle Publishing. p. 1999. ISBN 978-1-4629-1063-2.

- "Sailor Mo's Cosplay – Kimono Accessories". Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- "兵児帯". 百科事典マイペディア / kotobank.jp. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- "角帯". 百科事典マイペディア / kotobank.jp. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- Masayuki Murata. 明治工芸入門 pp. 104–106. Me no Me, 2017 ISBN 978-4907211110

- Yūji Yamashita. 明治の細密工芸 pp. 80–81. Heibonsha, 2014 ISBN 978-4582922172

- JapaneseKimono.com. "Children's Kimono". Archived from the original on 2009-03-15. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- Toma-san. "Archived copy" 七五三の着付け、女の子七歳編 (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2008-12-10. Retrieved 2009-03-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- nickn. Sortie. "Ayame Obi musubi". Archived from the original on 2010-08-02. Retrieved 2009-03-06.

- nickn. Sortie. "Bara Obi musubi". Archived from the original on 2010-08-02. Retrieved 2009-03-06.

- Dalby, pp. 337–348

- Yamanaka, pp. 66–70

- Yamanaka, pp. 7-12, 29-30

- nickn. Sortie. "Washikusa Obi musubi". Archived from the original on 2010-08-03. Retrieved 2009-03-06.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Obi. |

- Bennett, Gary (1997). Aikido techniques & tactics. Human Kinetics Publisher. ISBN 0-88011-598-X.

- Dalby, Liza (2001). Kimono, Fashioning Culture. Vintage. ISBN 0-09-942899-7.

- Fält, Olavi K.; Nieminen, Kai; Tuovinen, Anna; Vesterinen, Ilmari (2006). Japanin kulttuuri (in Finnish). Otava. ISBN 951-1-12746-2.

- Goodman, Fay (1998). The Ultimate Book of Martial Arts. Lorenz Books. ISBN 1-85967-778-9.

- Yamanaka, Norio (1986). The book of kimono. Kondansha International. ISBN 0-87011-785-8.