Repetitive strain injury

A repetitive strain injury (RSI) is an injury to part of the musculoskeletal or nervous system caused by repetitive use, vibrations, compression or long periods in a fixed position.[1] Other common names include repetitive stress disorders, cumulative trauma disorders (CTDs), and overuse syndrome.[2]

| Repetitive strain injury | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cumulative trauma disorders, repetitive stress injuries, repetitive motion injuries or disorders, occupational or sports overuse syndromes |

| |

| Poor ergonomic techniques by computer users is one of many causes of repetitive strain injury | |

| Specialty | Sports medicine, performing arts medicine, orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Sore wrists, aching, pulsing pain, tingling, extremity weakness |

| Complications | Torn ligaments |

| Causes | Repetitive actions, poor technique |

| Risk factors | Sedentary lifestyle, smoking, alcohol consumption |

| Prevention | Proper technique, regular rests, regular exercise |

Signs and symptoms

Some examples of symptoms experienced by patients with RSI are aching, pulsing pain, tingling and extremity weakness, initially presenting with intermittent discomfort and then with a higher degree of frequency.[3]

Definition

Repetitive strain injury (RSI) and associative trauma orders are umbrella terms used to refer to several discrete conditions that can be associated with repetitive tasks, forceful exertions, vibrations, mechanical compression, sustained or awkward positions, or repetitive eccentric contractions.[1][4][5] The exact terminology is controversial, but the terms now used by the United States Department of Labor and the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) are musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) and work-related muscular skeletal disorders (WMDs).[2]

Examples of conditions that may sometimes be attributed to such causes include tendinosis (or less often tendinitis), carpal tunnel syndrome, cubital tunnel syndrome, De Quervain syndrome, thoracic outlet syndrome, intersection syndrome, golfer's elbow (medial epicondylitis), tennis elbow (lateral epicondylitis), trigger finger (so-called stenosing tenosynovitis), radial tunnel syndrome, ulnar tunnel syndrome, and focal dystonia.[1][5][6]

A general worldwide increase since the 1970s in RSIs of the arms, hands, neck, and shoulder has been attributed to the widespread use in the workplace of keyboard entry devices, such as typewriters and computers, which require long periods of repetitive motions in a fixed posture.[7] Extreme temperatures have also been reported as risk factor for RSI.[8]

Risk factors

Occupational risk factors

Workers in certain fields are at risk of repetitive strains. Most occupational injuries are musculoskeletal disorders, and many of these are caused by cumulative trauma rather than a single event.[9] Miners and poultry workers, for example, must make repeated motions which can cause tendon, muscular, and skeletal injuries.[10][11] Jobs that involve repeated motion patterns or prolonged posture within a work cycle, or both, may be repetitive. Young athletes are predisposed to RSIs due to an underdeveloped musculoskeletal system.[12]

Psychosocial factors

Factors such as personality differences to work-place organization problems. Certain workers may negatively perceive their work organization due to excessive work rate, long work hours, limited job control, and low social support. Previous studies shown elevated urinary catecholamines (stress-related chemicals) in workers with RSI. Pain related to RSI may evolve into chronic pain syndrome particularly for workers who do not have supports from co-workers and supervisors.[13]

Non-occupational factors

Age and gender are important risk factors for RSIs. The risk of RSI increases with age.[14] Women are more likely affected than men because of their smaller frame, lower muscle mass and strength, and due to endocrine influences. In addition, lifestyle choices such as smoking and alcohol consumption are recognizable risk factors for RSI. Recent scientific findings indicate that obesity and diabetes may predispose an individual to RSIs by creating a chronic low grade inflammatory response that prevents the body from effectively healing damaged tissues. [15]

Diagnosis

RSIs are assessed using a number of objective clinical measures. These include effort-based tests such as grip and pinch strength, diagnostic tests such as Finkelstein's test for De Quervain's tendinitis, Phalen's contortion, Tinel's percussion for carpal tunnel syndrome, and nerve conduction velocity tests that show nerve compression in the wrist. Various imaging techniques can also be used to show nerve compression such as x-ray for the wrist, and MRI for the thoracic outlet and cervico-brachial areas. Utilization of routine imaging is useful in early detection and treatment of overuse injuries in at risk populations, which is important in preventing long term adverse effects.[12]

Treatment

There are no quick fixes for RSI. Early diagnosis is critical to limiting damage.[16] The RICE treatment is used as the first treatment for many muscle strains, ligament sprains, or other bruises and injuries. RICE is used immediately after an injury happens and for the first 24 to 48 hours after the injury. These modalities can help reduce the swelling and pain.[17] Commonly prescribed treatments for early-stage RSIs include analgesics, myofeedback, biofeedback, physical therapy, relaxation, and ultrasound therapy.[6] Low-grade RSIs can sometimes resolve themselves if treatments begin shortly after the onset of symptoms. However, some RSIs may require more aggressive intervention including surgery and can persist for years.

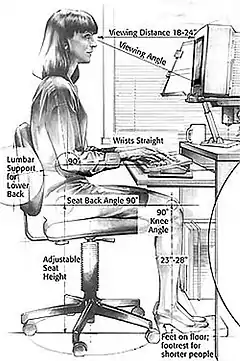

Although there are no "quick fixes" for RSI, there are effective approaches to its treatment and prevention.[18] One is that of ergonomics, the changing of one's environment (especially workplace equipment) to minimize repetitive strain. Another is specific massage techniques such as trigger point therapy and related techniques such as the Alexander Technique. Licensed massage therapists specializing in RSI, as well as physical therapists and chiropractors, generally provide hands-on therapy, but also expect that the patient supplement and reinforce the office-visit therapy sessions with daily (or several times daily) exercises, self-massage, and stretching as prescribed by the practitioner.

General exercise has been shown to decrease the risk of developing RSI.[19] Doctors sometimes recommend that RSI sufferers engage in specific strengthening exercises, for example to improve sitting posture, reduce excessive kyphosis, and potentially thoracic outlet syndrome.[20] Modifications of posture and arm use are often recommended.[6][21]

History

Although seemingly a modern phenomenon, RSIs have long been documented in the medical literature. In 1700, the Italian physician Bernardino Ramazzini first described RSI in more than 20 categories of industrial workers in Italy, including musicians and clerks.[22] Carpal tunnel syndrome was first identified by the British surgeon James Paget in 1854.[23] The April 1875 issue of The Graphic describes "telegraphic paralysis."[24]

The Swiss surgeon Fritz de Quervain first identified De Quervain’s tendinitis in Swiss factory workers in 1895.[25] The French neurologist Jules Tinel (1879–1952) developed his percussion test for compression of the median nerve in 1900.[26][27][28] The American surgeon George Phalen improved the understanding of the aetiology of carpal tunnel syndrome with his clinical experience of several hundred patients during the 1950s and 1960s.[29]

Society

Specific sources of discomfort have been popularly referred to by terms such as Blackberry thumb, PlayStation thumb,[30] Rubik's wrist or "cuber's thumb",[31] stylus finger,[32] and raver's wrist,[33] and Emacs pinky.[34]

See also

Notes

- "Public Employees Occupational Safety and Health Program of the New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2006.

- CDC (28 March 2018). "Template Package 4". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- "Repetitive Strain Injury: What is it and how is it caused?" (PDF). Selikoff Centers for Occupational Health. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- Afsharnezhad, Taher; Nourshahi, Maryam; Parvardeh, Siavash (2016). "Functional and Histopathological Changes in Muscle After 6-Weeks Repetitive Strain Injury: A 10-Week Follow Up of Aged Rats". International Journal of Applied Exercise Physiology. 5 (4): 74–80. ProQuest 1950381705.

- van Tulder M, Malmivaara A, Koes B (May 2007). "Repetitive strain injury". Lancet. 369 (9575): 1815–22. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.589.3485. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60820-4. PMID 17531890.

- Verhagen, Arianne P.; Bierma-Zeinstra, Sita M. A.; Burdorf, Alex; Stynes, Siobhán M.; de Vet, Henrica C. W.; Koes, Bart W. (2013). "Conservative interventions for treating work-related complaints of the arm, neck or shoulder in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD008742. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008742.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6485977. PMID 24338903.

- "Welcome to the RSI Awareness Website". Rsi.org.uk. 17 November 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- Diwaker, H. N.; Stothard, J. (1995). "What do doctors mean by tenosynovitits and repetitive strain injury?". Occupational Medicine (Oxford, England). 45 (2): 97–104. doi:10.1093/occmed/45.2.97. PMID 7718827.

- Cumulative Trauma Disorders in the Workplace. U.S. CDC-NIOSH Publication 95-119. 1995.

- Mining Publication: Risk Profile of Cumulative Trauma Disorders of the Arm and Hand in the U.S. Mining Industry U.S. CDC-NIOSH web site.

- "CDC - Poultry Industry Workers - NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- Paz, D. A.; Chang, G. H.; Yetto Jr, J. M.; Dwek, J. R.; Chung, C. B. (November 2015). "Upper extremity overuse injuries in pediatric athletes: Clinical presentation, imaging findings, and treatment". Clinical Imaging. 39 (6): 954–964. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2015.07.028. PMID 26386655.

- Faucett, J.; Rempel, D. (1994). "VDT-related musculoskeletal symptoms: interactions between work posture and psychosocial work factors". American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 26 (5): 597–612. doi:10.1002/ajim.4700260503. PMID 7832208.

- Ashbury, F. D. (1995). "Occupational repetitive strain injuries and gender in Ontario 1986 to 1991". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 37 (4): 479–85. doi:10.1097/00043764-199504000-00021. PMID 7670905.

- Del Buono, A.; Battery, L.; Denaro, V.; MacCauro, G.; Maffulli, N. (2011). "SAGE Journals: Your gateway to world-class journal research". International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology. 24 (1 Suppl 2): 45–50. doi:10.1177/03946320110241s209. PMID 21669137.

- Cook J (February 1988). "Work related repetitive movement problems. A successful management plan". Aust Fam Physician. 17 (2): 104–5. PMID 3358746.

- "How to Use the R.I.C.E Method for Treating Injuries". 27 August 2014.

- Copeland, CS (May–June 2014). "It's All in the Wrist...Or Is It? Symptoms, Sources, and Solutions for Repetitive Stress Injury" (PDF). Healthcare Journal of New Orleans.

- Ratzlaff, C. R.; J. H. Gillies; M. W. Koehoorn (April 2007). "Work-Related Repetitive Strain Injury and Leisure-Time Physical Activity". Arthritis & Rheumatism. 57 (3): 495–500. doi:10.1002/art.22610. PMID 17394178.

- Kisner, Carolyn; Colby, Lyn Allen (2007). Therapeutic Exercise: Foundations and Techniques (5th ed.). Philadelphia: F. A. Davis. p. 473. ISBN 978-0-8036-1584-7.

- Berkeley Lab. Integrated Safety Management: Ergonomics Archived 5 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Website. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- Ramazzini (1700). De Morbis Artificum Diatriba [Diseases of Workers]. Modena.

- Pearce, J. M. (April 2009). "James Paget's median nerve compression (Putnam's acroparaesthesia)". Pract Neurol. 9 (2): 96–9. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2008.166140. PMID 19289560.

- "Victorian London - Disease - 'telegraphic paralysis'".

- Ahuja, N. K.; Chung, K. C. (2004). "Fritz de Quervain, MD (1868–1940): stenosing tendovaginitis at the radial styloid process". The Journal of Hand Surgery. 29 (6): 1164–70. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.05.019. PMID 15576233.

- Tinel, J. (1917). Nerve wounds. London: Baillère, Tindall and Cox.

- Tinel, J. (1915). "Le signe du fourmillement dans les lésions des nerfs périphériques". Presse Médicale. 47: 388–389.

- Tinel, J. (1978). "The 'tingling sign' in peripheral nerve lesions". In Spinner, M. (ed.). Injuries to the Major Branches of Peripheral Nerves of the Forearm. Translated by Kaplan, E. B. (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: WD Saunders Co. pp. 8–13. ISBN 0-7216-8524-2.

- "FMC Acquires Turner White Communications". 2 August 2017.

- Vaidya, Hrisheekesh Jayant (March 2004). "Playstation thumb". The Lancet. 363 (9414): 1080. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15865-0. PMID 15051306.

- Waugh D (September 1981). "Cuber's thumb". N. Engl. J. Med. 305 (13): 768. doi:10.1056/nejm198109243051322. PMID 7266622.

- "5 Modern Technology Strain Injuries | Carpal Tunnel Syndrome". Ctsplace.com. 30 December 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- Raver’s Wrist

- http://ergoemacs.org/emacs/emacs_pinky.html

External links

- Repetitive Strain Injuries at Curlie

- Musculoskeletal disorders from the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA)

- Amadio PC (January 2001). "Repetitive stress injury". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 83-A (1): 136–7, author reply 138–41. doi:10.2106/00004623-200101000-00018. PMID 11205849.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |