Revisionist Zionism

Revisionist Zionism was an ideology developed by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, who advocated a "revision" of the "practical Zionism" of David Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann which was focused on independent individuals' settling of Eretz Yisrael (Land of Israel). Revisionism differed from other types of Zionism primarily in its territorial maximalism. Revisionists had a vision of occupying the full territory, and insisted upon the Jewish right to sovereignty over the whole of Eretz Yisrael, which they equated to the whole territory covered by the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine, including Transjordan. It was the chief ideological competitor to the dominant socialist Labor Zionism.

In 1935, after the Zionist Executive rejected Jabotinsky's political program and refused to state that "the aim of Zionism was the establishment of a Jewish state", Jabotinsky resigned from the World Zionist Organization. He founded the New Zionist Organization (NZO), known in Hebrew as Tzakh, to conduct independent political activity for free immigration and the establishment of a Jewish State.[1]

In its early years under Jabotinsky's leadership, Revisionist Zionism was focused on gaining support from Britain for settlement. Later, Revisionist groups independent of Jabotinsky's direction conducted campaigns of Zionist political violence against the British to drive them out of Mandatory Palestine to establish a Jewish state.

Revisionist Zionism has strongly influenced right-wing Israeli parties, principally the Herut and its successor, the Likud.

History

Revisionist Zionism was based on a vision of "political Zionism", which Jabotinsky regarded as following the legacy of Theodor Herzl, the founder of modern political Zionism. His main demand was the creation of Greater Israel on both sides of the Jordan River, and was against the partition of Palestine, such as suggested by the Peel Commission, with Arabs.

The 1921 British establishment of Transjordan (the modern-day state of Jordan) adversely affected this goal, and was a great setback for the movement. Before Israel achieved statehood in 1948, Revisionist Zionism became known for its advocacy of more belligerent, assertive postures and actions against both British and Arab control of the region.

Revisionism's foremost political objective was to establish and maintain the territorial integrity of the historical land of Israel; its representatives wanted to establish a Jewish state with a Jewish majority on both sides of the River Jordan. Jewish statehood was always a major ideological goal for Revisionism, but it was not to be gained at the price of partitioning Eretz Yisrael. Jabotinsky and his followers in Betar, the New Zionist Organization (NZO) and Hatzohar consistently rejected proposals to partition Palestine into an Arab state and a Jewish state. Menachem Begin, who came to embody Revisionist Zionism after the 1940 death of Jabotinsky, opposed the 1947 United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine. Revisionists regarded the subsequent partition of Palestine following the 1949 Armistice Agreements as illegitimate.[2]

During the first two decades after the Israeli Declaration of Independence in May 1948, the main revisionist party, Herut (founded in June 1948), remained in opposition. The party slowly began to revise its ideology in an effort to change this situation and to gain political power. While Begin maintained the Revisionist claim to Jewish sovereignty over all of Eretz Israel, by the late 1950s, control over the East Bank of the Jordan ceased to be integral to Revisionist ideology. Following Herut's merger with the Liberal Party in 1965, references to the ideal of Jewish sovereignty over "both banks of the Jordan" appeared less and less frequently. By the 1970s, the legitimacy of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan was no longer questioned. In 1994 the complete practical abandonment of the "both banks" principle was apparent when an overwhelming majority of Likud Knesset Members (MKs) voted in favour of the Israel–Jordan Treaty of Peace.[3]

The day the Six-Day War started in June 1967, the Revisionists, as part of the Gahal faction, joined the national unity government under Prime Minister Levi Eshkol. Begin served in the cabinet of Israel for the first time. Ben-Gurion's Rafi party also joined.[4] The war brought to an end Labour Party's previous efforts to undercut Revisionism because on the eve of the war, the dominant party, Mapai, believed it had to include the Revisionist opposition in an emergency national-unity government. This action helped legitimize the views of the opposition. It also showed that the dominant party no longer felt that it could monopolize power.[5]

This unity arrangement lasted until August 1970, when Begin and Gahal left Golda Meir's government. Some sources indicate the resignation was due to disagreements over the Rogers Plan and its "in-place" cease-fire with Egypt along the Suez Canal;[6] other sources, including William B. Quandt, note that Begin left the unity government because the Labour Party, by formally accepting UN 242 in mid-1970, had accepted "peace for withdrawal" on all fronts. On August 5, 1970, Begin himself explained his resignation before the Knesset, saying:

"As far as we are concerned, what do the words 'withdrawal from territories administered since 1967 by Israel' mean other than Judea and Samaria.[sic] Not all the territories; but by all opinion, most of them."[7][8]

Following Israel's capture of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in the 1967 Six-Day War, Revisionism's territorial aspirations concentrated on these territories. These areas were far more central to ancient Jewish history than the East Bank of the Jordan and most of the areas within Israel's post-1949 borders. In 1968 Begin defined the "eternal patrimony of our ancestors" as "Jerusalem, Hebron, Bethlehem, Judea, [and] Shechem [Nablus]" in the West Bank. In 1973 Herut's election platform called for the annexation of the West Bank and Gaza. When Menachem Begin became leader of the broad Likud coalition (1973) and soon afterwards Prime Minister (in office: 1977–1983), he considerably modified Herut's expansive territorial aims. The party's aspiration to unite all of mandatory Palestine under Jewish rule was scaled down. Instead, Begin spoke of the historic unity of Israel in the West Bank, even hinting that he would make territorial concessions in the Sinai as part of a complete peace settlement.[9]

When Begin finally came to power in the 1977 election, his overriding concern as Prime Minister (1977–1983) was to maintain Israeli control over the West Bank and Gaza.[10][11] In 1981 he declared to a group of Jewish settlers: "I, Menachem, the son of Ze'ev and Hasia Begin, do solemnly swear that as long as I serve the nation as Prime Minister we will not leave any part of Judea, Samaria, [or] the Gaza Strip."[12] One of the main mechanisms for accomplishing this objective was the establishment of Jewish settlements. Under Labour governments, between 1967 and 1977, the Jewish population of the territories reached 3,200 ; Labour's limited settlement activity was predicated upon making a future territorial compromise when the majority of the territory would be returned to Arab control. By contrast, the Likud's settlement plan aimed to settle 750,000 Jews all over the territories in order to prevent a territorial compromise. As a result, by 1984, there were about 44,000 settlers outside East Jerusalem.

Begin's foreign policy

In the diplomatic arena, Begin pursued his core ideological objective in a relatively pragmatic manner. He held back from annexing the West Bank and Gaza, recognizing that this was not feasible in the short term, due to international opposition.[2] He signed the Camp David Accords (1978) with Egypt that referred to the "legitimate rights of the Palestinians" (although Begin insisted that the Hebrew version referred only to "the Arabs of Eretz Yisrael" and not to "Palestinians"). Begin also promoted the idea of autonomy for the Palestinians, albeit only a "personal" autonomy that would not give them control over any territory. But his uncompromising stance in the negotiations over Palestinian autonomy from 1979 to 1981 led to the resignations of the more moderate Moshe Dayan and Ezer Weizman, Foreign and Defense Ministers, respectively, both of whom left the Likud government.

According to Weizman, the significant concessions Begin made to the Egyptians in the Camp David Accords and the Egypt–Israel Peace Treaty of the following year were motivated, in part, by his ideological commitment to the eventual annexation of the territories.[13] By removing the most powerful Arab state from the conflict, reducing international (mainly American) pressure for Israeli concessions on the issue of the territories, and prolonging inconclusive talks on Palestinian autonomy, Begin was buying time for his government's settlement activities in the territories. Begin continued to vow that territory which was part of historic Eretz Israel in the West Bank and Gaza would never be returned. His adamant stand on the territory became an obstacle to extending the 1979 peace treaty.[9]

The Revisionist ideological stand concerning the territories has continued, although it has moderated somewhat and become more "pragmatic" in the years since, as discussed below.

Jabotinsky and Revisionist Zionism

After World War I, Jabotinsky was elected to the first legislative assembly in the Yishuv, and in 1921 he was elected to the Executive Council of the Zionist Organization (known as the World Zionist Organization after 1960). He quit the latter group in 1923, thanks mainly to differences of opinion with its chairman, Chaim Weizmann. In 1925, Jabotinsky formed the Revisionist Zionist Alliance, in the World Zionist Congress to advocate his views, which included increased cooperation with Britain on transforming the entire Mandate for Palestine territory, including Palestine itself and Transjordan, on opposite sides of the Jordan River, into a sovereign Jewish state, loyal to the British Empire. To this end, Jabotinsky advocated for mass Jewish immigration from Europe and the creation of a second Jewish Legion to guard a nascent Jewish state at inception. A staunch anglophile, Jabotinsky wished to convince Britain that a Jewish state would be in the best interest of the British Empire, perhaps even an autonomous extension of it in the Middle East.

When, in 1935, the Zionist Organization failed to accept Jabotinsky's program, he and his followers seceded to form the New Zionist Organization. The NZO rejoined the ZO in 1946. The Zionist Organization was roughly composed of General Zionists, who were in the majority, followers of Jabotinsky, who came in a close second, and Labour Zionists, led by David Ben-Gurion, who comprised a minority yet had much influence where it mattered, in the Yishuv.

Despite its strong representation in the Zionist Organization, Revisionist Zionism had a small presence in the Yishuv, in contrast to Labour Zionism, which was dominant among kibbutzim and workers, and hence the settlement enterprise. General Zionism was dominant among the middle class, which later aligned itself with the Revisionists. In the Jewish Diaspora, Revisionism was most established in Poland, where its base of operations was organized in various political parties and Zionist Youth groups, such as Betar.[14] By the late 1930s, Revisionist Zionism was divided into three distinct ideological streams: the "Centrists", the Irgun, and the "Messianists".

Jabotinsky later argued for a need to establish a base in the Yishuv, and developed a vision to guide the Revisionist movement and the new Jewish society on the economic and social policy centered around the ideal of the Jewish middle class in Europe. Jabotinsky believed that basing the movement on a philosophy contrasting with the socialist-oriented Labour Zionists would attract the support of the General Zionists.

In line with this thinking, the Revisionists transplanted into the Yishuv their own youth movement, Betar. They also set up a paramilitary group, [Irgun, a labour union, the National Labor Federation in Eretz-Israel, and their own health services. The latter were intended to counteract the increasing hegemony of Labour Zionism over community services via the Histadrut and address the refusal of the Histadrut to make its services available to Revisionist Party members.

Irgun Tsvai Leumi

The Irgun (short for Irgun Tsvai Leumi, Hebrew for "National Military Organization" ארגון צבאי לאומי) had its roots initially in the Betar youth movement in Poland, which Jabotinsky founded. By the 1940s, they had transplanted many of its members from Europe and the United States to Palestine. The movement, now acting autonomously from the Hatzohar leadership in Poland, decided to organize locally, as its small membership was increasingly overshadowed by Labour Zionists, who were predominantly focused on settling the land. While Jabotinsky continued to lobby the British Empire, the Irgun, under the leadership of people such as David Raziel and later Menachem Begin, fought politically against the Labour Zionists and militarily against the British for the establishment of a Jewish state, independent of any orders from Jabotinsky.

Acting often in conflict (but at times, also in coordination) with rival clandestine militias such as the Haganah and the Lehi (or Stern Group), the Irgun's efforts would feature prominently in the armed struggles against British and Arab forces alike in the 1930s and 1940s, and ultimately become decisive in the closing events of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. After 1948, members of the Irgun were variously demobilised, or incorporated directly into the nascent Israeli Defense Forces; and on the political front, Irgunist ideology found a new vehicle of expression in the Herut (or "Freedom") Party.

Lehi

.svg.png.webp)

The movement called Lehi and nicknamed the "Stern Gang" by the British, was led by Avraham "Yair" Stern, until his death. Stern did not join the Revisionist Zionist party in university but instead joined another group called Hulda. He formed Lehi in 1940 as an offshoot from Irgun, which was initially named Irgun Zvai Leumi be-Yisrael (National Military Organization in Israel or NMO). Following Stern's death in 1942—shot by a British police officer—and the arrest of many of its members, the group went into eclipse until it was reformed as "Lehi" under a triumvirate of Israel Eldad, Natan Yellin-Mor, and Yitzhak Shamir. Lehi was guided also by spiritual leader Uri Zvi Greenberg. The Lehi, in particular their members in prison, were encouraged in their struggle by Rabbi Aryeh Levin, a greatly respected Jewish sage of the time. Shamir became the Prime Minister of Israel forty years later.

Irgun—and, to a lesser extent, Lehi—were influenced by the romantic nationalism of Italian nationalist Giuseppe Garibaldi. The movement's activities were independent of any diaspora leadership, but were backed by several figures in the diaspora. While the Irgun stopped its activities against the British during World War II, at least until 1944, Lehi continued guerrilla warfare against the British authorities. It considered the British rule of Mandatory Palestine to be an illegal occupation, and concentrated its attacks mainly against British targets (unlike the other underground movements, which were also involved in fighting against Arab paramilitary groups).

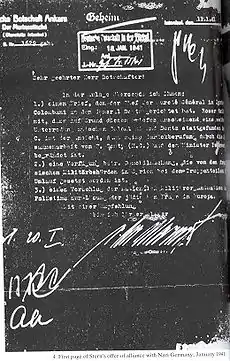

In 1940, Lehi proposed intervening in the Second World War on the side of Nazi Germany to attain their help in expelling Britain from Mandate Palestine and to offer their assistance in "evacuating" the Jews of Europe.[16] Late in 1940, Lehi representative Naftali Lubenchik was sent to Beirut where he met the German official Werner Otto von Hentig (see Lehi (group)#Contact with Nazi Germany).

Lehi prisoners captured by the British generally refused to present a defence when brought to trial in British courts. They would only read out statements in which they declared that the court, representing an occupying force, had no jurisdiction over them. For the same reason, Lehi prisoners refused to plead for amnesty, even when it was clear that this would have spared them from the death penalty. In two cases, Lehi men killed themselves in prison to deprive the British of the ability to hang them.

Tensions between the Irgun and Lehi simmered until the two groups forged an alliance during the 1947–1949 Palestine war.

Ideology

Ideologically, Revisionism advocated the creation of a Jewish state on both sides of the Jordan River, that is, a state which would include the present-day Israel, as well as West Bank, Gaza and all or part of the modern state of Jordan. Nevertheless, the terms of the Mandate allowed the mandatory authority, Britain, to restrict Jewish settlement in parts of the mandate territory. In 1922, before the Mandate officially came into effect in 1923, Transjordan was excluded from the terms regarding Jewish settlement. In the Churchill White Paper of 1922, the British Government had made clear that the intent expressed by the Balfour Declaration was that a Jewish National Home should be created 'in' Palestine, not that the whole of Palestine would become a Jewish National Home. All three Revisionist streams, including Centrists who advocated a British-style liberal democracy, and the two more militant streams, which would become Irgun and Lehi, supported Jewish settlement on both sides of the Jordan River; in most cases, they differed only on how this should be achieved. (Some supporters within Labor Zionism, such as Mapai's Ben-Gurion also accepted this interpretation for the Jewish homeland.) Jabotinsky wanted to gain the help of Britain in this endeavour, while Lehi and the Irgun, following Jabotinsky's death, wanted to conquer both sides of the river independently of the British. The Irgun stream of Revisionism opposed power-sharing with Arabs. In 1937, Jabotinsky rejected the conclusion of the Peel Commission, which proposed a partition of Palestine between Jews and Arabs; it was however accepted by the Labor Zionists.[17] On the topic of "transfer" (expulsion of the Arabs), Jabotinsky's statements were ambiguous. In some writings he supported the notion, but only as an act of self-defense, in others he argued that Arabs should be included in the liberal democratic society that he was advocating, and in others still, he completely disregarded the potency of Arab resistance to Jewish settlement, and stated that settlement should continue, and the Arabs be ignored.

Fascist views within the movement

Up to 1933, a small portion of members from the national-messianist wing of Revisionism were inspired by the fascist movement of Benito Mussolini. Abba Ahimeir was attracted to fascism for its staunch anti-communism and its focus on rebuilding the glory of the past, which national-messianists such as Uri Zvi Greenberg felt had much connection to their view of what the Revisionist movement should be.

Abba Ahimeir's ideology was based in Oswald Spengler's monumental study on the decline of the West, but his Zionist orientation caused him to adapt its ultimate conclusions. Achimeir's basic assumption was that liberal bourgeois European culture was degenerate, and deeply eroded from within by an excess of liberalism and individualism. Socialism and communism were portrayed as "overcivilized" ideologies. Fascism on the other hand, like Zionism, was a return to the roots of the national culture and the historical past. According to Achimeir, Italian Fascism was not anti-Semitic or anti-Zionist, whereas communist ideology and praxis were intrinsically so.

He also developed a favourable attitude toward fascist praxis and its psycho-politics, such as the principle of the all-powerful leader, the use of propaganda to generate a spirit of heroism and duty to the homeland, and the cultivation of youthful vitality (as manifested in the fascist youth movements). Ahimeir joined the Revisionist movement in 1930, but before joining he wrote a regular column entitled "From the Notebook of a Fascist" in the unaffiliated but pro-Revisionist magazine Doar Hayom. He crafted his pro-fascistic views in these columns, and also wrote an article in 1928 titled "On the Arrival of Our Duce" to celebrate Jabotinsky's visit to Palestine, and propose a new direction for the Revisionist movement, more in line with Achimeir's views.[18]

When Ahimeir was on trial in 1932 for having disrupted a public lecture at Hebrew University, his lawyer, Zvi Eliahu Cohen, argued "Were it not for Hitler's anti-Semitism, we would not oppose his ideology. Hitler saved Germany." Tom Segev has remarked, "This was not an unconsidered outburst." An editorial in the Revisionist newspaper Hazit Haam praised Cohen's "brilliant speech." It continued, that "Social Democrats of all stripes believe that Hitler's movement is an empty shell (but) we believe that there is both a shell and a kernel. The anti-Semitic shell is to be discarded, but not the anti-Marxist kernel. The Revisionists would fight the Nazis only to the extent that they were anti-Semites."[18]

In 1933, when Hitler came to power, the newspaper, whose editors were Revisionist Party members, praised Nazism as a German national liberation movement and said that Hitler had saved Germany from Communism. Jabotinsky responded by threatening to have the newspaper's editors expelled if they repeated such "kow-towing" to Hitler.[19]

Irgun to Likud

The Irgun largely followed the Centrists' ideals but with a much more hawkish outlook toward Britain's involvement in the Mandate, and an ardently nationalist vision of society and government. After the establishment of the State of Israel, it was the Irgun wing of the Revisionist Party that formed Herut, which in turn eventually formed the Gahal party when the Herut and Liberal parties formed a united list called Gush Herut Liberalim (or the Herut-Liberal Bloc). In 1973 the new Likud Party was formed by a group of parties dominated by the Revisionist Herut/Gahal. After the 1977 Knesset elections it became the dominant party in a governing coalition, and remains an important force in Israeli politics until today. In the 2006 elections, the Likud lost many of its seats to the Kadima party. The Likud bounced back in Israel's 2009 Knesset elections, garnering 27 seats, although still less than Kadima's 28 seats. In spite of this right-of-center parties who favored a Likud-led coalition, comprised the majority; Likud was chosen to form the coalition. The party re-emerged as the strongest party in the Knesset in the 2013 elections and leads the government today. In the years since the 1977 election, particularly in the last decade, Likud has undergone a number of splits to its right, including the 1998 departure of Benny Begin, son of Herut founder Menachem Begin (he rejoined Likud in 2008), and in 2005 experienced a split to its left with the departure of Ariel Sharon and his followers to form Kadima.

While the initial core group of Likud leaders such as Israeli Prime Ministers Begin and Yitzhak Shamir came from Likud's Herut faction, later leaders, such as Benjamin Netanyahu (whose father was Jabotinsky's secretary) and Ariel Sharon, have come from or moved to the "pragmatic" Revisionist wing.

See also

References

- "Ze'ev Jabotinsky", J source (biography), Jewish virtual library.

- Rynhold, Jonathan; Waxman, Dov (March 2008), "Ideological change and Israel's disengagement from Gaza", Political Science Quarterly, 123: 11–37, doi:10.1002/j.1538-165X.2008.tb00615.x.

- Shelef, Nadav (Spring 2004). "From 'Both Banks of the Jordan' to the 'Whole Land of Israel': Ideological Change in Revisionist Zionism". Israel Studies. 9: 125–48..

- Factional and Government Make-Up of the Sixth Knesset, IL: Knesset.

- Pennings, Paul; Lane, Jan-Erik (1998), Comparing party system change, p. 144, ISBN 9780415165501.

- "The Zealot". Newsweek. May 30, 1977.

But he quit in 1970 when Prime Minister Golda Meir, under pressure from Washington, renewed a cease-fire with Egypt along the Suez Canal.

- Quandt, William B. Quandt, Peace Process, American Diplomacy and the Arab-Israeli Conflict since 1967, pp. 194ff.

-

Compare: Quandt, William B. (2001) [1993]. Peace Process: American Diplomacy and the Arab-Israeli Conflict Since 1967 (2 ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 438. ISBN 9780520223745. Retrieved 2018-02-26.

On August 5, 1970, Begin himself explained before the Knesset why he was resigning from the cabinet: 'As far as we are concerned, what do the words "withdrawal from territories administered since 1967 by Israel" mean other than Judea and Samaria.[sic] Not all the territories; but by all opinion, most of them.'

- Peretz, Don (1994), The Middle East today, pp. 318–9, ISBN 9780275945763.

- Peleg, Ilan (1987), Begin's Foreign Policy 1977–83, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- Sofer, Sasson (1988), Begin: an anatomy of leadership, London: Blackwell.

- "Menachem Begin". The Jerusalem Post. May 10, 1981.; cited in Rynhold and Waxman, Ideological change and Israel's disengagement from Gaza

- Weizman, Ezer (1981), The Battle for Peace, New York: Doubleday, p. 151

- (in English) David Wdowiński (1963). And We Are Not Saved. New York: Philosophical Library. p. 222. ISBN 0802224865. Note: Chariton and Lazar were never co-authors of Wdowiński's memoir. Wdowiński is considered the "single author."

- Heller 1995, p. 86.

- Shindler, Colin (1995). The land beyond promise: Israel, Likud and the Zionist dream. IB Tauris. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-86064-774-1.

- Shelef 2018, pp. 29, 83-4.

- Segev, Tom, The Seventh Million: Israelis and the Holocaust, p. 23.

- Schechtman, Fighter and Prophet, p. 216.

Bibliography

- Heller, Joseph (1995). The Stern Gang: Ideology, Politics and Terror, 1940–49. Frank Cass. ISBN 0-7146-4558-3.

- Gilbert, Sir Martin (2008) [1998]. Israel: A History. London: Black Swan. ISBN 9780552774284.

- Shelef, Nadav (2018). Evolving Nationalism: Homeland, Identity, and Religion in Israel, 1925–2005. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501729874.

- Shlaim, Avi (2014). The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World. Penguin.

- Jabotinsky, Ze'ev (1939). Writings: On the Road to Statehood (in Hebrew). Jerusalem.

- Goldberg, David J. (Spring 1996). "To the Promised Land Built By Israel and the Hidden Logic of the Iron Wall". Israel Studies. 1 (1).

- Shindler, Colin (2008). A History of Modern Israel. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521615389.