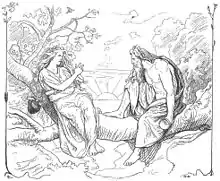

Sága and Sökkvabekkr

In Norse mythology, Sága (Old Norse: [saːɣa], possibly meaning "seeress"[1]) is a goddess associated with the location Sökkvabekkr (Old Norse: [sɔkːwabekːr]; "sunken bank", "sunken bench", or "treasure bank"[2]). At Sökkvabekkr, Sága and the god Odin merrily drink as cool waves flow. Both Sága and Sökkvabekkr are attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and in the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. Scholars have proposed theories about the implications of the goddess and her associated location, including that the location may be connected to the goddess Frigg's fen residence Fensalir and that Sága may be another name for Frigg.

Etymology

The etymology of the name Sága is generally held to be connected to the Old Norse verb sjá, meaning "to see" (from Proto-Germanic *sehwan). This may mean that Sága is to be understood as a seeress. Since Frigg is referred to as a seeress in the poem Lokasenna, this etymology has led to theories connecting Sága to Frigg. Rudolf Simek says that this etymology raises vowel problems and that a link to saga and segja (meaning "say, tell") is more likely, yet that this identification is also problematic.[3]

Attestations

In the Poetic Edda poem Grímnismál, Sökkvabekkr is presented fourth among a series of stanzas describing the residences of various gods. In the poem, Odin (disguised as Grímnir) tells the young Agnar that Odin and Sága happily drink there from golden cups while waves resound:

- Benjamin Thorpe translation:

- Sökkvabekk is fourth o'er which is named the gelid waves resound

- Odin and Saga there,

- joyful each day,

- from golden beakers quaff.[4]

- Henry Adams Bellows translation:

- Sökkvabekk is the fourth, where cool waves flow,

- And amid their murmur it stands;

- There daily do Othin and Saga drink

- In gladness from cups of gold.[5]

In the Poetic Edda poem Helgakviða Hundingsbana I, the hero Sinfjötli references Sága in the name of a location found in a stanza where Sinfjötli flyts with Guðmundr. The location name, nes Ságu,[6] has been variously translated as "Saga's Headland,"[7] "Saga's Cape,"[8] and "Saga's ness"[9] Part of the stanza may be missing and, due to this, some editors have joined it with the stanza prior.[8]

Sága is mentioned once in both the Prose Edda books Gylfaginning and Skáldskaparmál, while Sokkvabekk is only mentioned once, in Gylfaginning. In chapter 35 of Gylfaginning, High tells Gangleri (described as king Gylfi in disguise) about the ásynjur. High follows a description of Frigg and her dwelling Fensalir with "Second is Saga. She dwells in Sokkvabekk, and that is a big place."[10] In chapter 75 of the book Skáldskaparmál, Sága is present among a list of 27 ásynjur, but no information is provided about her there.[11]

Theories

John Lindow says that due to similarity between Sökkvabekkr and Fensalir, "Odin's open drinking with Sága", and the potential etymological basis for Sága being a seeress has "led most scholars to understand Sága as another name for Frigg."[12] Stephan Grundy states that the words Sága and Sökkvabekkr may be by-forms of Frigg and Fensalir, respectively, used for the purpose of composing alliterative verse.[13]

Britt-Mari Näsström theorizes that "Frigg's role as a fertility goddess is revealed in the name of her abode, Fensalir [...]", that Frigg is the same as Sága, and that both the names Fensalir and Sökkvabekkr "imply a goddes [sic] living in the water and recall the fertility goddess Nerthus". Näsström adds that "Sökkvabekkr, the subterranean water, alludes to the well of Urd, hidden under the roots of Yggdrasil and the chthonic function, which is manifest in Freyja's character."[14]

Rudolf Simek says that Sága should be considered "one of the not closer defined Asyniur" along with Hlín, Sjöfn, Snotra, Vár, and Vör, and that they "should be seen as female protective goddesses." Simek adds that "these goddesses were all responsible for specific areas of the private sphere, and yet clear differences were made between them so that they are in many ways similar to matrons."[3]

19th century scholar Jacob Grimm comments that "the gods share their power and influence with goddesses, the heroes and priests with wise women." Grimm notes that Sökkvabekkr is "described as a place where cool waters rush" and that Odin and Sága "day to day drink gladly out of golden cups." Grimm theorizes that the liquid from these cups is:

- the drink of immortality, and at the same time of poesy. Saga may be taken as wife or as daughter of Oðinn; in either case she is identical to him as god of poetry. With the Greeks the Musa was a daughter of Zeus, but often hear of three or nine Muses, who resemble our wise women, norns and schöpferins (shapers of destiny), and dwell beside springs or wells. The cool flood well befits the swanwives, daughters of Wish. Saga can be no other than our sage (saw, tale), the 'mære' [...] personified and deified.[15]

Notes

- Orchard (1997:136).

- Orchard (1997:152) and Lindow (2001:265) have "sunken bank". Byock (2005:175) has "sunken bank or bench". Simek (2007:297) has "sunken bank" or "treasure bank."

- Simek (2007:274).

- Thorpe (1866:21).

- Bellows (1936:88–89).

- Guðni Jónsson ed., verse 39, á nesi Ságu.

- Larrington (1999:119).

- Bellows (1923:112).

- Grimm (1883:910).

- Faulkes (1995:29).

- Faulkes (1995:175).

- Lindow (2001:265).

- Grundy (1999:62).

- Näsström (1996:88–89).

- Grimm (1883:910-911).

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sága. |

- Bellows, Henry Adams (Trans.) (1923). The Poetic Edda: Translated from the Icelandic with an introduction and notes by Henry Adams Bellows. New York: The American-Scandinavian Foundation.

- Bellows, Henry Adams (Trans.) (1936). The Poetic Edda. Princeton University Press. New York: The American-Scandinavian Foundation.

- Byock, Jesse (Trans.) (2005). The Prose Edda. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044755-5

- Faulkes, Anthony (Trans.) (1995). Snorri Sturluson: Edda. First published in 1987. London: Everyman. ISBN 0-460-87616-3

- Grimm, Jacob (James Steven Stallybrass Trans.) (1888). Teutonic Mythology: Translated from the Fourth Edition with Notes and Appendix by James Stallybrass. Volume III. London: George Bell and Sons.

- Grundy, Stephan (1999). "Freyja and Frigg" as collected in Billington, Sandra and Green, Miranda. The Concept of the Goddess. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-19789-9

- Guðni Jónsson (Ed.) Helgakviða Hundingsbana I. online at Heimskringla project.

- Larrington, Carolyne (Trans.) (1999). The Poetic Edda. Oxford World's Classics. ISBN 0-19-283946-2

- Lindow, John (2001). Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515382-0

- Näsström, Britt-Mari (1996). "Freyja and Frigg - two aspects of the Great Goddess" as presented in Shamanism and Northern Ecology: Papers presented at the Regional Conference on Circumpolar and Northern Religion, Helsinki, May 1990. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-014186-8

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-34520-2

- Simek, Rudolf (2007) translated by Angela Hall. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. D.S. Brewer. ISBN 0-85991-513-1

- Thorpe, Benjamin (Trans.) (1866). Edda Sæmundar Hinns Frôða: The Edda of Sæmund the Learned. Part I. London: Trübner & Co.