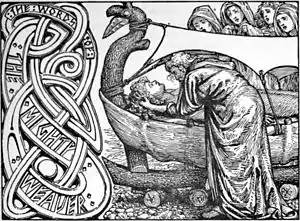

Vafþrúðnir

Vafþrúðnir (Old Norse "mighty weaver"[1]) is a wise jötunn in Norse mythology. His name comes from Vaf, which means weave or entangle, and thrudnir, which means strong or mighty. Some interpret it to mean "mighty in riddles".[2] It may be anglicized Vafthruthnir or Vafthrudnir. In the Poetic Edda poem Vafþrúðnismál, Vafþrúðnir acts as (the disguised) Odin's host and opponent in a deadly battle of wits that results in Vafþrúðnir's defeat.

Characterization

A small portion of Poetic Edda provides some context and description of Vafthrudnir. While contemplating his visit to the giant, Odin's wife Frigg offers a warning for him to be wary of this particular giant because, "Amid all the giants an equal in might, To Vafthruthnir know I none."[3] At this point however Odin has already insisted,

And Vafthruthnir fain would find;

fit wisdom old with the giant wise

Myself would I seek to match.[3]

From this discussion one can glean that Vafthrudnir is distinguished from other giants as being especially wise and mighty. This is the only description provided of Vafthrudnir in Poetic Edda prior to his actual encounter with Odin. We know that Vafthrudnir is recognized for his knowledge of the past, present, and future states of the world, which is precisely why Odin decides to pay him a visit in order to test his skill against those of the reputed Vafthrudnir.

Contest of wits with Odin

The contest of wits is found in the Poetic Edda poem Vafþrúðnismál and is in an answer and response format. Each participant asks the other a series of questions about beings and events in the past, present, and future of the nine worlds. Odin defers to Vafþrúðnir, who proceeds to probe his guest's knowledge of the stallions that pull Day and Night across the sky. Odin correctly answers that Skinfaxi pulls Day across the world and Hrimfaxi draws the Night. Odin also offers extra details about the stallions' appearance and characteristics. Vafþrúðnir continues by testing Odin's knowledge of Iving and Ragnarök before allowing his guest the chance to question him.

Odin inquires about the origin of the earth and heavens. Vafþrúðnir responds correctly that the heavens and earth were formed from the flesh of Ymir. He demonstrates expertise on the topic by specifically listing which parts of Ymir's body created heaven and earth. Odin then asks about the origin of the moon and sun. The giant correctly answers that the moon and sun are the son and daughter of the giant Mundilfari. They were assigned their place in the sky so that men could tell the passing of time. Odin proceeds to ask about many topics including Dellingr, Nór, the fathers of Winter and Summer, Bergelmir, Aurgelmir, Hraesvelg, Njörðr, the Einherjar, Niflheim, Ragnarök, Fenrir, Álfröðull, and what will happen after the world has ended.[3][4] Both participants exhibit extensive knowledge of their mythological world.

Odin then breaks the established pattern of questioning and states that Vafþrúðnir, in all his wisdom, should be able to tell his guest what Odin whispered into the ear of his son, Baldr, before he was burned on the funeral pyre. At this point, Vafþrúðnir recognizes his guest for who he really is. He responds that no one except his guest, Odin, would have such knowledge unless Baldr himself reveals the secret. Vafþrúðnir willingly submits to his fate and proclaims that Odin will always be wiser than the wisest.

Parallels to literature and popular culture

The structure of Odin's and Vafþrúðnir's encounter has parallels with the Gestumblindi and King Heidrek incident in the Norse Hervarar saga and The Hobbit’s “Riddles in the Dark” between Bilbo and Gollum.[5] Many of the riddles in these events are alike and all end with the same type of question.[6] The riddle contest between King Heidrek and Gestumblindi, Odin in disguise yet again, ends with the same question that he posed to Vafþrúðnir about his final words to Baldr.[7] Bilbo’s final question to Gollum is about the contents of his pocket. Odin and Bilbo break the established structure of a riddle contest and ask a virtually impossible yet simply worded question instead of a riddle about an object or mythological event. Gollum and King Heidrek were both angry and frustrated with their opponent. King Heidrek becomes violent and swings his sword, Tyrfing, at Odin. Gollum demands a total of three guesses due to the nature of Bilbo’s question. This is in contrast to how Vafþrúðnir is depicted as being calm and accepting of his fate when bested by Odin. Odin's riddle contest with Vafþrúðnir influenced not only other works within Norse mythology, but also more modern works of literature such as The Hobbit.

Notes

- Orchard (1997:170).

- Du Chaillu, P. B. (1889).

- Vafþrúðnismál, tr. Henry Adams Bellows, at Wikisource

- Dronke, U. (1997).

- Tolkien, J.

- Honegger, T. (2013).

- Turville-Petre, E. O. G.

References

- Du Chaillu, P. B. (1889). The Viking Age: The Early History, Manners, and Customs of the Ancestors of the English Speaking Nations. (Vol. 2). C. Scribner's sons.

- Dronke, U. (1997). The poetic edda: Mythological poems (Vol. 2). Oxford University Press, USA.

- Guerber, H. A. (2012). Myths of the Norsemen: From the Eddas and Sagas. Courier Dover Publications

- Jakobsson, Ármann. (2008). A contest of cosmic fathers. Neophilologus, 92(2), 263–277.

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-34520-2

- Skaldskaparmal, in Edda. Anthony Faulkes, Trans., Ed. (London: Everyman, 1996).

- Viking Society for Northern Research. (1905). Saga Book of the Viking Society for Northern Research (Vol. 4).

- Tolkien, J. (1982). Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel. The Hobbit, or, There and back again. Random House LLC, 1982.

- St Clair, G. (1995). An Overview of the Northern Influences on Tolkien's Works. Proceedings of the J.R.R. Tolkien Centenary Conference edited by Patricia Reynolds and Glen H. GoodKnight.

- Turville-Petre, E. O. G. (1976). Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks (Vol. 2). Viking Society for Northern Research.

- Honegger, T.(2013). My Most Precious Riddle: Eggs and Rings Revisited. Tolkien Studies 10(1), 89-103. West Virginia University Press. Retrieved March 24, 2014, from Project MUSE database.